Team:Cambridge/Society/Questionnaire/Results

From 2011.igem.org

Contents |

The iGEM census

Preface

When a new scientific field is just budding, outreach organisations and events are key to bringing in new minds and catalysing expansion. Synthetic biology is no different, and the iGEM (international Genetically Engineered Machine) competition initiated by Tom Knight, Drew Endy and Randy Rettberg is arguably the biggest outreach effort that has ever been launched in this area. The annual competition encourages students to dedicate a single summer vacation to learning and applying the basic principles of synthetic biology to create a genetically engineered organism that can be ‘useful’ to society. iGEM has grown exponentially since its humble beginnings as an IAP at MIT in 2003 to become an international community with thousands of participants from all over the world. Many iGEM teams from around the world have conducted their own outreach events, introducing synthetic biology to an even wider audience including children who have not even left primary school.

One question strikes us, however - just how effective has iGEM been as means to engage more scientists to work in synthetic biology? What has its effect been on its participants, and the field as a whole? By making some advances to answer this question, valuable insight can be made into what similar outreach programmes can work to achieve, and what they can do to improve their effectiveness.

To this end, a short online questionnaire was designed and distributed by the Cambridge iGEM team in 2011, with the aim of creating a ‘census’ of the students who have taken part in iGEM teams over the past 8 years of the competition’s history. With over 60 respondents, we have amassed a sufficient amount of data to make some valid analyses; although we do urge caution against drawing any broad conclusions about the competition, since our sample is only a statistically insignificant “”% of the population size. However, on an individual scale, we do believe that we have a lot of interesting tales to tell.

We would like to thank the many iGEM team supervisors from around the globe who have helped us to get in touch with these alumni, and without which this study would not have been possible.

Notes

- The respondents were not required to complete the survey, and so not all applicants responded to every question - as a result, the total number of respondents varies for each question.

- We assume familiarity with the iGEM competition in the remainder of this report. If necessary, you can find out more about iGEM on their website, at ung.igem.org.

- On our graphs, we refrain from using percentages and deal with raw figures instead due to our small sample size. In this way, we wish to make it evident when our data may be more anecdotal than statistically significant.

Contents

The student sample

The iGEM projects

The impact of iGEM on career paths

Is iGEM self-sustaining?

Conclusions

The student sample

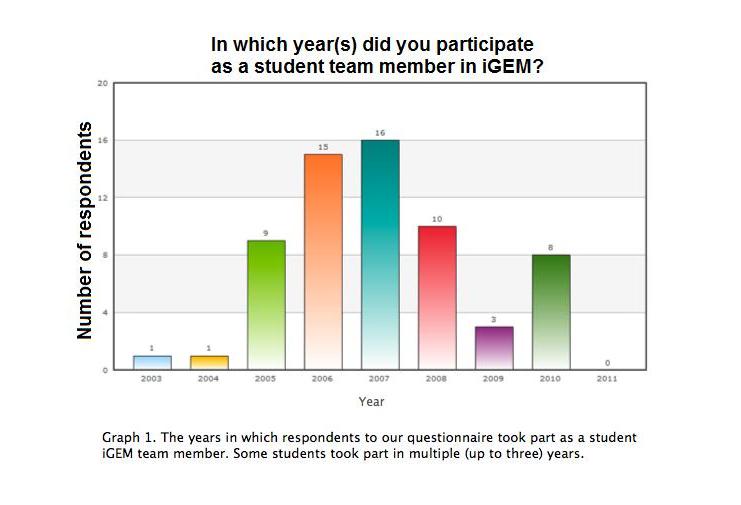

The target population of the iGEM outreach initiative was sampled for this study - this consisted of the ‘alumni’ who initially took part in the iGEM competition as a student team member from 2003-2010 inclusive. The iGEM alumni who participated in our research were linked to the survey (hosted on www.esurveyspro.com) via various routes, including direct email contact as well as Twitter, Facebook and our iGEM wiki page.

We attempted to focus on alumni who participated in the earliest years of the competition, since their careers would be more likely to have progressed further after taking part in iGEM than more recent participants. Unfortunately, it was difficult to get in contact with students from 2003 and 2004, since it was only in 2005 that iGEM existed formally in its own right, as opposed to being an option within the internal IAP (independent activities period) programme at MIT.

We attempted to focus on alumni who participated in the earliest years of the competition, since their careers would be more likely to have progressed further after taking part in iGEM than more recent participants. Unfortunately, it was difficult to get in contact with students from 2003 and 2004, since it was only in 2005 that iGEM existed formally in its own right, as opposed to being an option within the internal IAP (independent activities period) programme at MIT.

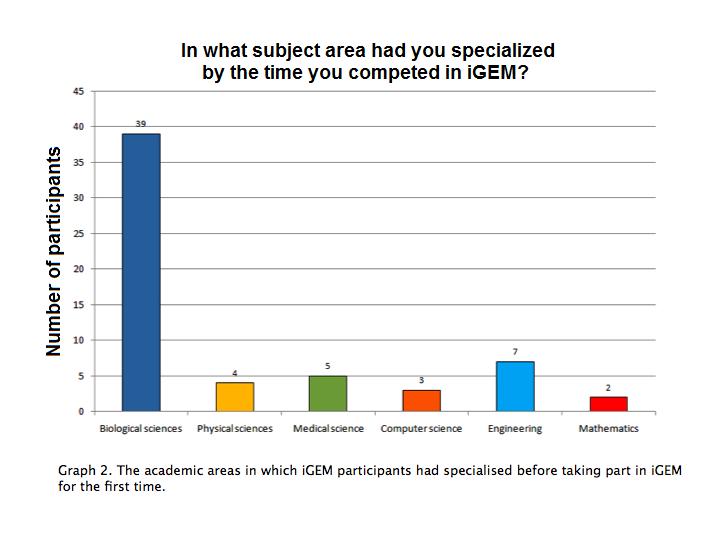

The vast majority of the respondents had specialised in biological sciences (although this spanned very different fields including microbiology, biochemistry, immunology and pharmacology) by the time they participated in iGEM, indicating that they were already set on a career in biology before taking part. Significantly, however, one third of respondents were not specialised in biology, with their backgrounds ranging from physics and engineering to computer science, mathematics and medicine. These students came from various years of the competition, and were present from the very beginning of the competition in 2003 through to the most recent years. iGEM seems to have been quite successful in attracting participants from various backgrounds, which is crucial in the development of such an interdisciplinary field.

The vast majority of the respondents had specialised in biological sciences (although this spanned very different fields including microbiology, biochemistry, immunology and pharmacology) by the time they participated in iGEM, indicating that they were already set on a career in biology before taking part. Significantly, however, one third of respondents were not specialised in biology, with their backgrounds ranging from physics and engineering to computer science, mathematics and medicine. These students came from various years of the competition, and were present from the very beginning of the competition in 2003 through to the most recent years. iGEM seems to have been quite successful in attracting participants from various backgrounds, which is crucial in the development of such an interdisciplinary field.

The respondents came from teams across North America and Europe - although an effort was made to collect data from universities in other continents, we were not successful. This is partially due to the fact that the vast majority of iGEM teams were either North American or European up until 2009, when there was a large expansion in Asia. However, we are aware that this still introduces a bias to our results that needs to be bourne in mind.

The iGEM Projects

The significance of the actual projects that are undertaken by iGEM teams is a key part of the contribution that the iGEM community brings to the field of synthetic biology, together with building the online and physical library of standard DNA parts and of course inspiring students to participate in the new science. A criticism that has been made of the competition is that since the students have such little time to work on their projects, they either end up with ‘gimmicky’ machines or are not able to make significant headway in achieving the ambitious goals they set themselves at the outset. Evidently, more work must be done beyond the summer in order to develop projects further, but has this been the case in the past?

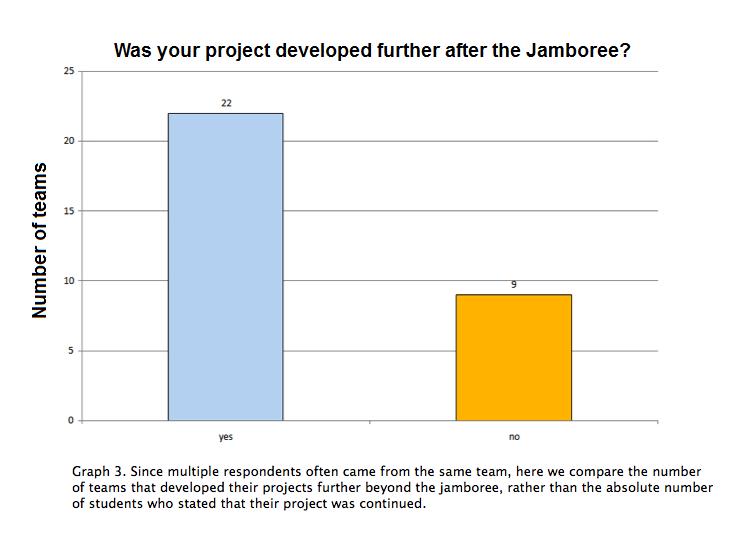

Graph 3 shows that over two thirds of the projects that respondents to the survey took part in were continued beyond the jamboree, though the extent of the work done varied significantly between projects. Some of the projects were only slightly augmented, with some further BioBrick modification, sometimes finishing off projects that weren’t completed in time for the jamboree. This work was sometimes done by the original team members, but also often carried on by their iGEM mentors or supervisors, who were often professors or post-Doctoral students in the lab they were working at. More recently, the judging criteria of the iGEM competition has encouraged new teams to further characterise the BioBrick parts submitted to the Registry by previous iGEM teams. This is important, since many parts that have been submitted have little or no documentation so future teams can do a lot to improve the usefulness of the BioBricks available. Some teams, such as Slovenia, build upon the work they do year on year, and have been extremely successful in the competition (winning 3 times in the past 5 years in Slovenia’s case). Teams such as Cambridge 2009 have also had their BioBricks requested from other scientists, who have subsequently used them in their own research.

Graph 3 shows that over two thirds of the projects that respondents to the survey took part in were continued beyond the jamboree, though the extent of the work done varied significantly between projects. Some of the projects were only slightly augmented, with some further BioBrick modification, sometimes finishing off projects that weren’t completed in time for the jamboree. This work was sometimes done by the original team members, but also often carried on by their iGEM mentors or supervisors, who were often professors or post-Doctoral students in the lab they were working at. More recently, the judging criteria of the iGEM competition has encouraged new teams to further characterise the BioBrick parts submitted to the Registry by previous iGEM teams. This is important, since many parts that have been submitted have little or no documentation so future teams can do a lot to improve the usefulness of the BioBricks available. Some teams, such as Slovenia, build upon the work they do year on year, and have been extremely successful in the competition (winning 3 times in the past 5 years in Slovenia’s case). Teams such as Cambridge 2009 have also had their BioBricks requested from other scientists, who have subsequently used them in their own research.

Impressively, several projects were also continued by some members of the team as part of their Master’s or PhD thesis. Some papers were also published by the students which were printed in acclaimed journals such as Nature and Cell (team UTAustin 2004,2005,2006) and presentations made at conferences such as BioSynBio. This is indicative of the scientific importance of the work done. Some titles of the publications can be found in the Appendix.

Through our research, we have found that some notable work has been produced following on from projects undertaken as entries in the iGEM competition. In this way, iGEM has allowed students to give a direct contribution to research in synthetic biology, very soon after participating. The students are often inspired to produce very ambitious biological machines, often aiming to solve a well-known global problem, such as facilitating the breakdown of hazardous chemicals (e.g. crude oil, TU Delft 2010), sustainable production of biomaterials (e.g. biocellulose, Imperial College London 2009). As a result, there is often much media coverage of iGEM projects (e.g. Bioluminescence by Cambridge 2010 was featured in New Scientist magazine), raising the public profile of synthetic biology in a positive light. In this sense, it can thus be argued that iGEM projects have done much to both publicise synthetic biology as well as contribute significantly to the science.

The Impact of iGEM on Career Paths

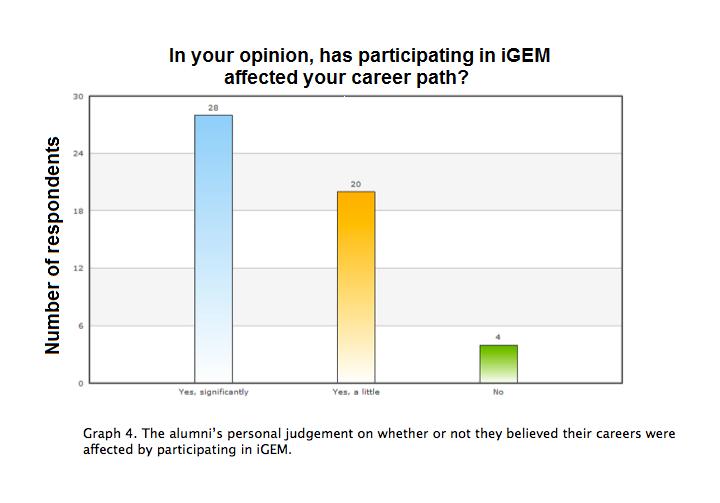

We asked iGEM alumni whether or not they personally believed that iGEM affected their subsequent career paths. The results are shown in Graph 4.

Over 90% of respondents thought that iGEM did have an effect, and over 50% thought that the effect was significant. The reasons for this varied widely; the most popular included:

Over 90% of respondents thought that iGEM did have an effect, and over 50% thought that the effect was significant. The reasons for this varied widely; the most popular included:

Research experience (often a decisive factor in whether or not the students subsequently pursued a career in academia) Developed lab skills (useful in their later career, and influential on their CV) Networking opportunities (many students are currently working as PhD students with their iGEM mentor as their supervisors, or in other iGEM labs which they got in contact with during the jamboree) Many students were inspired to work in synthetic biology later in their careers (see Graph 6 below) Students became more open-minded to working outside their specialist fields and with people from different disciplines (almost every respondent was new to synthetic biology when taking part)

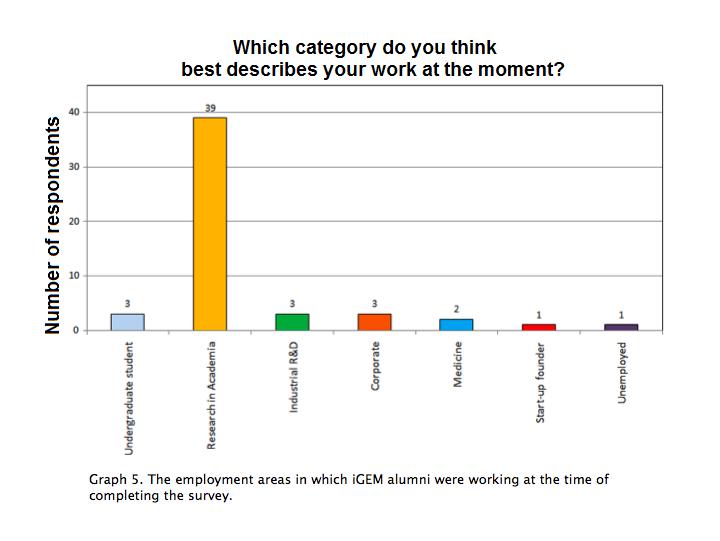

Graph 5 also shows that 75% of respondents were performing research in academia at the time of completing the survey - participating in iGEM was commonly said to be a valuable experience that helped students to choose such a career path. Conversely, a couple of alumni also stated that their experience in iGEM helped them to decide not to go into research.

Graph 5 also shows that 75% of respondents were performing research in academia at the time of completing the survey - participating in iGEM was commonly said to be a valuable experience that helped students to choose such a career path. Conversely, a couple of alumni also stated that their experience in iGEM helped them to decide not to go into research.

In addition, three alumni responding to our survey were co-founders of biotech startup companies (including Ginkgo Bioworks, www.diybio.org and Synbiota), all of which were related to synthetic biology, and cited participation in the iGEM competition as being crucial to their motivation for doing so.

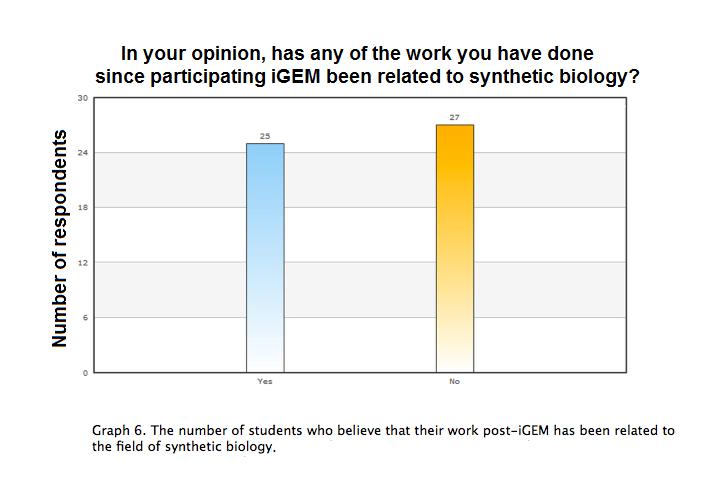

We also asked more specifically about whether or not taking part in iGEM actually inspired further participation in synthetic biology (Graph 6), which is key to judging the success of the outreach aspect of iGEM.

Almost half of our respondents did place their work within the field of synthetic biology, which is a very promising statistic given that all but one were new to the field prior to participating in the competition. In addition, several non-biologists (e.g. engineers) switched into biological research in areas such as systems biology and bioinformatics which they did not term ‘synthetic biology’, but are arguably very closely related. Biology students now working in other biological fields have also stated that the lab skills learned during iGEM have been extremely useful in their current research.

Almost half of our respondents did place their work within the field of synthetic biology, which is a very promising statistic given that all but one were new to the field prior to participating in the competition. In addition, several non-biologists (e.g. engineers) switched into biological research in areas such as systems biology and bioinformatics which they did not term ‘synthetic biology’, but are arguably very closely related. Biology students now working in other biological fields have also stated that the lab skills learned during iGEM have been extremely useful in their current research.

A couple of notes to bear in mind - several of the respondents who stated that they were working in synthetic biology were studying PhDs in the field, and some are considering moving away from the field afterwards. It must also be considered that our sample could be quite biased, since iGEM alumni who enjoyed participating in iGEM may have been more likely to find out about and complete our survey. Nevertheless, the effect of participating in iGEM for these alumni is significant, and may be considered by the organisers of iGEM as a big success.

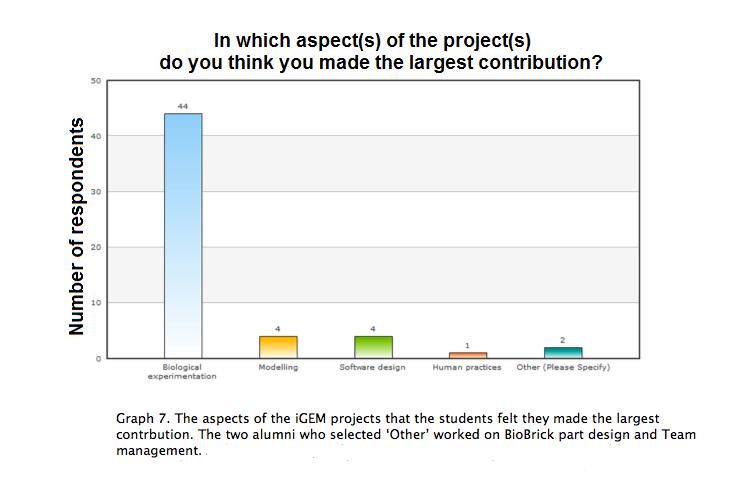

In order to shed more light on what particular aspects of participating in iGEM caused these effects, we also looked at where the individual students made their principle contribution to their projects.

The vast majority of respondents contributed principally to biological experimentation (or ‘wet-work’, as it is commonly termed) in their iGEM project - which is perhaps unsurprising given the practical nature of the competition. Almost all biologists focused on this side of the project, while students who focused on the other aspects of the project were all non-biologists, with the exception of a single biologist who worked on software design. However, approximately half of the non-biologists also named their largest contribution to the project to be biological experimentation. This suggests that, at least in some teams, new students have been introduced to biology through the iGEM programme. This has certainly been the case in our personal experience, as more than half of the Cambridge 2011 iGEM team were non-biologists, yet we all participated eagerly in wet-work. Engineers became specialists in making electrophoresis gels and Gibson assembly, while a physicist became heavily involved in protein extraction. As a consequence, several members of our team are now keen to participate in research with a strong biological bent in the future.

The vast majority of respondents contributed principally to biological experimentation (or ‘wet-work’, as it is commonly termed) in their iGEM project - which is perhaps unsurprising given the practical nature of the competition. Almost all biologists focused on this side of the project, while students who focused on the other aspects of the project were all non-biologists, with the exception of a single biologist who worked on software design. However, approximately half of the non-biologists also named their largest contribution to the project to be biological experimentation. This suggests that, at least in some teams, new students have been introduced to biology through the iGEM programme. This has certainly been the case in our personal experience, as more than half of the Cambridge 2011 iGEM team were non-biologists, yet we all participated eagerly in wet-work. Engineers became specialists in making electrophoresis gels and Gibson assembly, while a physicist became heavily involved in protein extraction. As a consequence, several members of our team are now keen to participate in research with a strong biological bent in the future.

Several other teams, however, seem to restrict students to focus on aspects of the project that play only to their strengths, so biology students would devote all their time to the wet-work while computer scientists (for example) would only work on modelling and software development. From our research, this restriction does not seem to have affected the influence that iGEM has on the students. For example, we have spoken to an engineering student who worked solely on modelling in her iGEM project, but subsequently (after some networking at the jamboree) took up a PhD in synthetic biology at another iGEM lab. We possess little more than anecdotal evidence, however, so more data needs to be gathered in order to draw any confident conclusions.

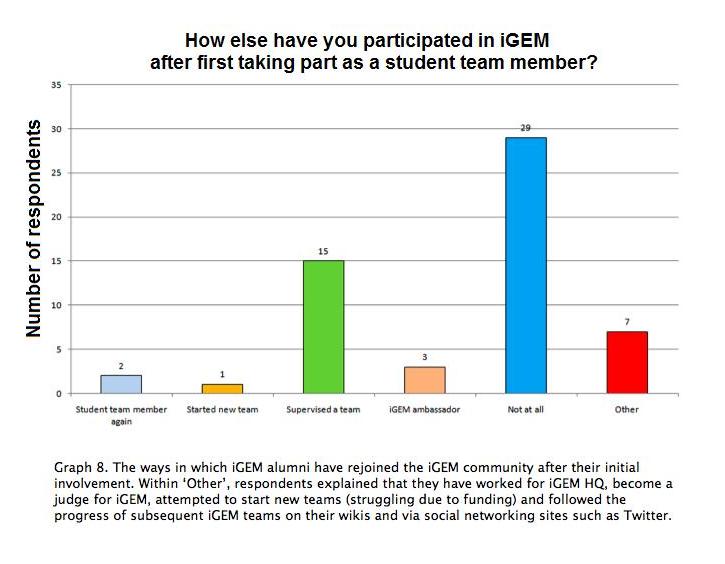

Is iGEM Self-Sustaining?

In order for an organisation to be sustainable over an extended period of time, it is crucial that there exists a continuing influx of people willing to participate in running it. We looked to find out whether or not iGEM alumni chose to be such people, since this would show that the participants enjoyed the experience to such an extent that they would willingly take part again, and perhaps believed in the effectiveness of the outreach programme. If a sufficient proportion of alumni were to contribute further to the iGEM community, it would also make the community self-sustaining, in that solely alumni of the programme itself would be required to keep the organisation running, with no other recruitment necessary (although also possible, and likely to be very welcome!).

Graph 8 shows that almost half of the respondents have participated in iGEM beyond being a student team member. The extent of involvement varied widely, from passively following the progress of new iGEM teams (and communicating with them via social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter) to working at iGEM HQ and becoming a member of the judging panel at the jamboree. Every level of administration seemed to have been covered, though the most popular means of participation was supervising/advising new teams. If this statistic were representative of the entire population of iGEM alumni, which looks to increase by several thousand students each year, then it would seem that iGEM is successfully self-sustaining. However, once again caution must be made against such sweeping statements due to the small size of our sample.

Conclusions

At the outset of our study, we sought to find out how successful iGEM has been as an outreach programme attracting students to the field of synthetic biology, and deduce what lessons could be learned in order to improve such efforts in the future. Though our research has been by no means complete, we do believe that we have garnered sufficient data to draw some tentative conclusions.

Generally, the iGEM alumni who responded to our questionnaire have indeed been influenced by their experiences in the competition. Almost half went on to work in synthetic biology in their future careers, and several more worked in closely related fields. This included many students who were not even studying a biological subject as an undergraduate.

Many of the projects were also continued well beyond the jamboree, with some findings published in highly-regarded scientific journals. This reflects the significance of the scientific findings that have been found or inspired within the context of iGEM projects, and shows that participants can not only learn about the field, but also contribute actively in the science.

These alumni also often went on to contribute further in the iGEM community, contributing to the sustainability of the organisation in the long-term.

There are some aspects of iGEM that we believe have been key to its success -

- The focus on creating machines that solve problems or create innovations with applications in the real world seems to be really inspirational to students, creating a really memorable experience.

- The freedom given to undergraduate students to participate in ‘PhD-style’ research gives them a valuable opportunity to find out whether or not they wish to work in academia, and also gives the students a chance to pursue the areas which interest them most within synthetic biology. This is arguably the best way to allow students to enjoy the experience as much as possible.

- The encouragement to create novel projects pushes students to the edge of current research, allowing students to feel a real sense of pride for their achievements, and inspires work that is genuinely significant in the wider scientific community.

- The target for outreach, undergraduate students, seems to be pitched to the right level. Within interdisciplinary teams, the students have a wide knowledge base, and are capable of both learning and understanding the challenging material without having to ‘dumb-down’ the science. However, the students are also at a stage in their career that is early enough for them to later specialise straightforwardly in synthetic biology before leaving education (for example, by undertaking a PhD in the subject).

- The jamboree has been cited by many alumni as the best aspect of the competition - it is an international scientific conference on a very large scale, and the enthusiasm of the thousands of students present make it quite unique. It has been cited by some alumni as the one key event that really made them want to return in the future, and networking opportunities are well-utilised.

In addition, however, we believe some improvements could be made to really maximise the success of iGEM as an outreach programme for synthetic biology:

- The importance of iGEM projects in the wider scientific community should be publicised by the organisation, with papers and conferences in which references have been made to iGEM projects highlighted. This is likely to inspire several other teams that have been successful in the iGEM competition to prepare similar publications, which could also be successful.

- The opportunities for further involvement by iGEM alumni in other aspects of the iGEM community should be made clear, and alumni should be encouraged to participate. This is likely to be popular, since almost all the students appeared to have enjoyed their first experience.

- Students from all backgrounds should be able to participate in all aspects of the project - although restricting students to their specific areas of expertise did not seem to have too much effect on their appreciation of the science, in our personal experience we believe it to be a lot more enjoyable when all the students take the opportunity to step out of their comfort zone and explore new fields - bringing a new sense of perspective that we value highly.

- Funding has been said to be an issue facing many teams, that have hampered efforts to both expand projects beyond the jamboree and also to start up new teams. If iGEM could perhaps lower the cost of participation, and/or offer special grants for particularly promising applications, this could help to over come the problem.

Despite leaving much room for improvement, within a few weeks of research we have managed to identify some key learning points that could be extremely useful for both the iGEM administrators and others hoping to lead similar outreach programmes. The most accurate and efficient way for organisers to find their strengths and weaknesses is straight from the participants themselves. We would like to encourage such practice to optimise outreach, in order to create enjoyable programmes that are maximally effective.

Appendix

Papers published as a result of extended iGEM projects:

Levskaya et al. Nature 2005 - Synthetic Biology: engineering Escherichia coli to see light

Tabor et al. Cell 2009 - A synthetic genetic edge detection program

Joshi et al. Desalination 2009 - Novel approaches to biosensors for detection of arsenic in drinking water (Presented at the Water and Sanitation in International Development and Disaster Relief (WSIDDR) International Workshop Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, 28-30 May 2008.

Mora et al. Analytical & Bioanalytical Chemistry 2011 - A pH-based biosensor for detection of arsenic in drinking water

Additional links:

An interview with an iGEM alumnus who co-founded diybio.org has also been posted to YouTube by user kkleiner, with the title “Singularity Hub Interviews Mac Cowell of diybio.org (diy bio)”. This interview was not conducted by the Cambridge iGEM team.

A blog set up by an iGEM alumnus who is “blogging about iGEM from the spectator’s viewpoint”: http://bloggingaboutigem.wordpress.com/

"

"