Team:Brown-Stanford/PowerCell/Background

From 2011.igem.org

(→H2O Content) |

|||

| (68 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Content}} | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Content}} | ||

| - | == ''' | + | == '''Photosynthesis and Mars''' == |

| - | + | ||

| + | Photosynthesis on Earth represents an effective way of converting solar to chemical energy on a large scale. The theoretical maximum yield of photosynthesis is approximately 11% of solar energy, with a practical efficiency of 3-6%.{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|A}} Added to the fact that this mechanism is robust (like all biological systems, photosynthetic organisms are self-replicating and self-repairing), photosynthesis would appear to be key for any energy generation purposes in an isolated, low-resource setting such as a Martian settlement. | ||

| - | + | Photosynthetic output depends on variables such as atmospheric composition and amount of accessible sunlight. In this section we introduce environmental conditions on Mars that need to be factored when assessing the usefulness of photosynthesis on Mars. | |

| + | === '''Atmosphere''' === | ||

| - | The | + | The Martian atmosphere is strikingly similar to our own atmosphere on Earth; we share the top four components in atmospheric composition (N2, O2, Ar, and CO2), albeit in varying amounts. {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|1}}<sup>,</sup>{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|2}} |

| - | === | + | {| border="1" align="center" style="text-align:center;" |

| + | |Mars | ||

| + | |Earth | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |6.36 mb pressure | ||

| + | |1014 mb pressure | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Carbon dioxide 95.32% | ||

| + | |Nitrogen 78.08% | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Nitrogen 2.70% | ||

| + | |Oxygen 20.95% | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Argon 1.60% | ||

| + | |Argon 9340 ppm | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Oxygen 0.13% | ||

| + | |Carbon dioxide 380 ppm | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Carbon monoxide 0.08% | ||

| + | |Neon 18.18 ppm | ||

| + | |} | ||

| - | |||

| + | Two main differences stand out: the atmosphere of Mars is overwhelmingly composed of CO2, and is much thinner than Earth's (0.6%) | ||

| - | + | Studies of lichen in Mars conditions suggest, however, that these differences may not be so bad.{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|3}} Photosynthetic activity is not diminished by a reduction to Mars atmospheric pressure (at least within the time frame of days). Furthermore, while Marslike levels of CO2 reduce photosynthetic activity by 60% (while keeping all other conditions within Earth ranges), the reduction to Mars pressure actually improves activity back to levels seen in wholly Earth conditions. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | This would suggest that the atmospheric composition and density of Mars, although inhospitable to human survival, are not incompatible to photosynthesis. | |

| + | === '''Solar irradiance''' === | ||

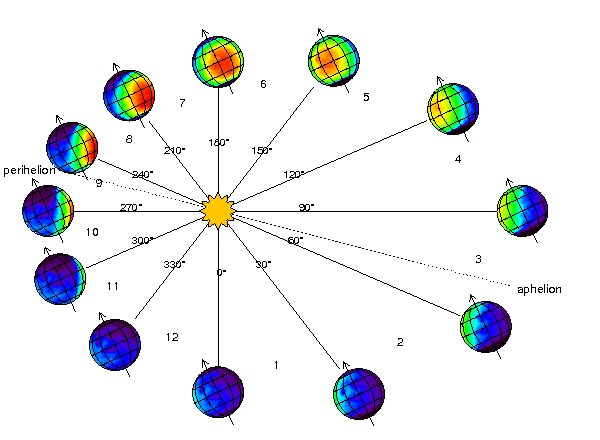

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Solar irradiance.jpg|300px|thumb|Mars solar cycle {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|3_2}}]] | ||

| + | A crucial factor to consider is the amount of solar energy available on Mars. Irradiance is a measure of how much solar radiation reaches a planet from the Sun, and is calculated from the length of the day-night cycle, distance from the Sun, position of orbit, etc. {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|3_1}} | ||

| - | + | Based on this method, solar irradiance at the mean distance between Mars and the Sun reaches a theoretical maximum of 590W/m<sup>2</sup> (assuming no distorting effects from the Martian atmosphere). | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | As a point of comparison, solar irradiance for Earth (measured from satellite instrumentation above the atmosphere) is approximately 1360W/m<sup>2</sup> {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|4}}. This means that Mars, which is 1.52 times as far from the Sun as Earth, receives 43% as much solar radiation per m<sup>2</sup>. | |

| - | + | To achieve a more meaningful measure of irradiance for photosynthesis, however, we have to account for filtering in the atmosphere before solar rays reach the Martian surface. | |

| - | + | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| - | + | === '''Particulates in the Martian atmosphere''' === | |

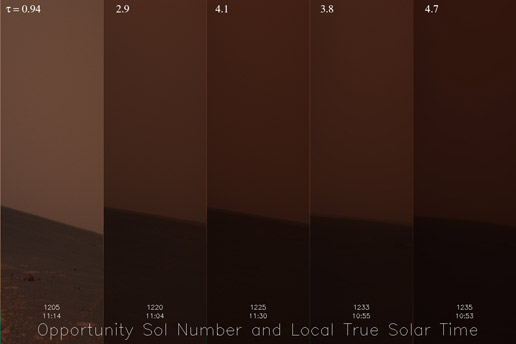

| + | Dust is a huge part of the Martian environment on a local and global scale! Particulate matter in the atmosphere can have a dramatic impact on the amount of sunlight reaching the Martian surface. For a vivid example, look at the decreasing visibility in this surface view from the NASA Opportunity rover amidst a brewing dust storm. Were this kind of disruption sustained for too long, any settlement or machine wholly dependent on solar energy would fail. | ||

| - | [[File:Brown-Stanford | + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Opportunity dust storm.jpg|300px|thumb|Deteriorating conditions on Mars [NASA]]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | τ (greek tau) stands for optical density, which is a measure of how transparent the atmosphere is. τ = 0 represents perfect transparency | ||

| + | |||

| + | Excluding the effect of regional storms, which interfere with sunlight in a temporary but unpredictable way, there are other dust dynamics we can consider as more constant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using ground measurements taken by NASA rovers over time, we know that the visible optical depth of the Martian atmosphere is τ = 0.9 [5] Put another way, this means that typically around 10^(-0.9) or 13%, of incoming sunlight is not scattered or absorbed before it hits the Martian surface. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

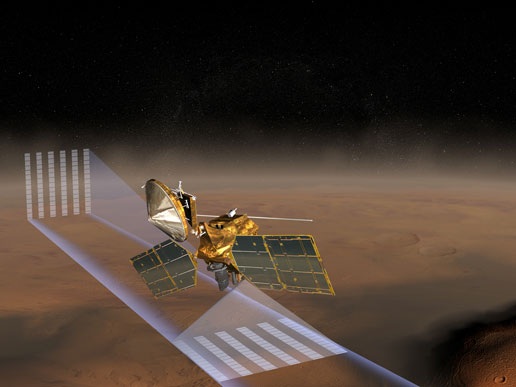

| + | Recent data gathered from satellites such as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) have begun to shed more light on the distribution and layering of dust. In particular, the MRO is able to take vertical profiles in addition to top-down images, offering a three-dimensional view{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|6}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford MRO MCS.jpg|200px|center|thumb|The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter [NASA]]] | ||

| + | |||

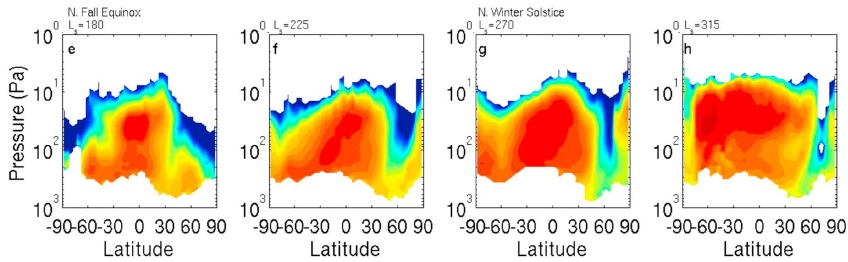

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford McCleese 2010 dust opacity.jpg|300px|center|thumb|Cross sections of dust opacity, with latitude on the X axis and altitude on the Y (measured in pressure); each image is a different time of year {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|6}}]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | From satellite imagery, researchers have also compiled maps showing the overall geographical distribution of dust coverage over a sample two-week span. {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|7}} Global dust patterns are a complex phenomenon, but must be considered in the placement of systems utilizing photosynthesis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Global dust.gif|center|frame|Dust patterning over a 14 day span {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|7}}, animation created by team]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | === '''Temperature''' === | ||

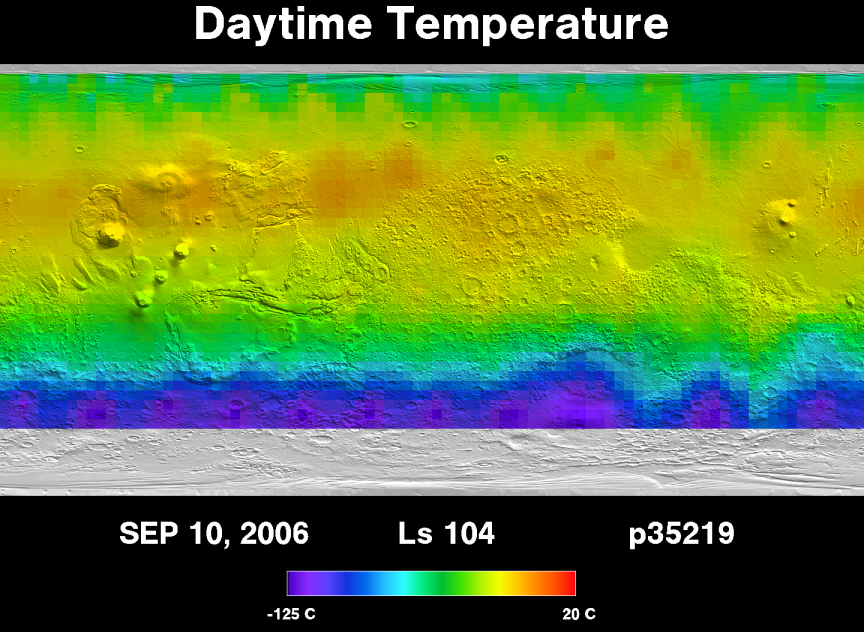

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Mars day temp.png|300px||right|thumb|Global daytime temperatures on Mars {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|7}}]] | ||

| + | The temperature on Mars is an obvious factor in considering the viability of microorganisms brought to the planet surface. Thermal emission spectrometry readings have been very thorough in generating a global map of temperatures. Temperature varies greatly between geographical location, altitude, and day/night, although as a whole the planet is significantly colder than Earth. Nonetheless, there are broad regions (especially in the intermediate latitudes) which experience temperatures comfortable for Earth life. | ||

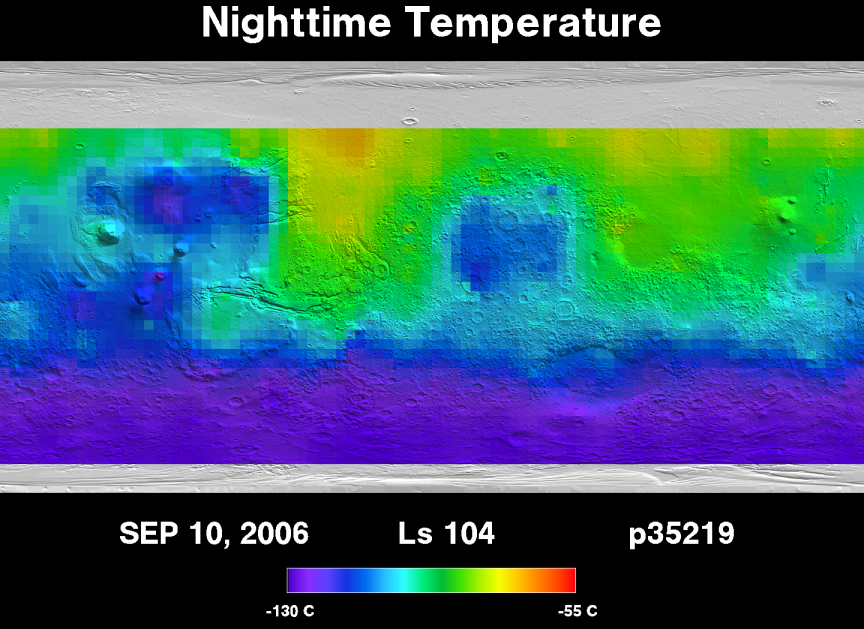

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Mars night temp.png|300px|right|thumb|Global nighttime temperatures on Mars {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|7}}]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Although any humans will obviously require extensive environmental protection due to temperature and a whole host of other factors, it seems that temperature does not necessarily preclude microbes from surviving on Mars. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | === '''H<sub>2</sub>O Content''' === | ||

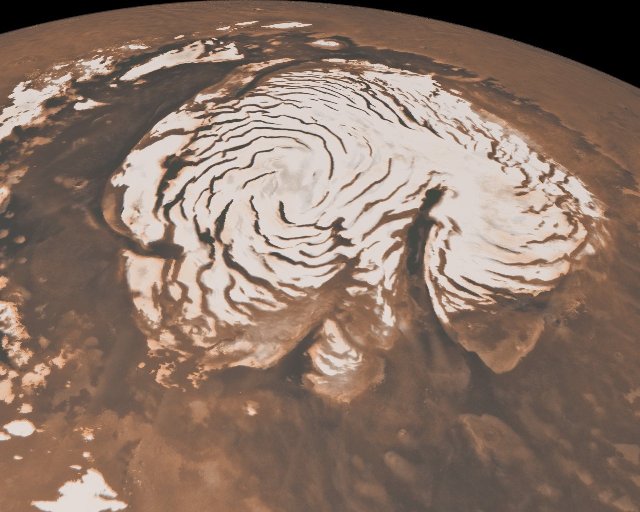

| + | As photosynthesis is a water-dependent process, the distribution of water on Mars is of interest. Enormous quantities of H2O are contained in the polar ice caps; the southern ice cap would submerge the entire planet in 11 meters of water if melted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Mars Ice Cap.jpg|300px||center|thumb]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Geographical features on the Martian surface suggest water erosion in quantities far greater than can be accounted for by ice in the polar regions.{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|8}} For this reason, scientists hypothesize large amounts of ground ice and subsurface reservoirs exist across the planet. Though there are no comprehensive surveys of subsurface water deposits, there have been numerous studies of yet another source. | ||

| + | |||

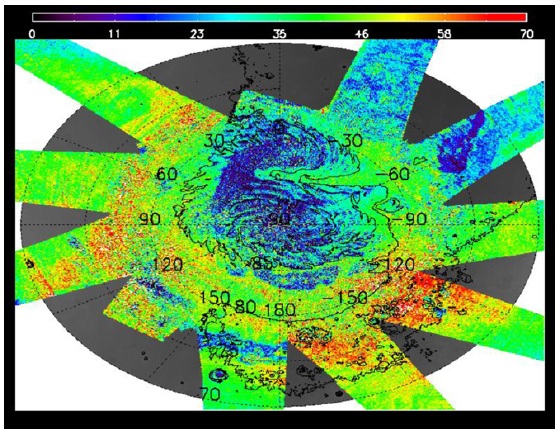

| + | Vapor content has been measured from several satellites orbiting Mars.{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|9}}<sup>,</sup>{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|10}}<sup>,</sup>{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|11}} Cameras circling above use spectrometers to image the planet and note the intensity of peaks at certain wavelengths corresponding to H2O. From this information, they can quantify the amount of water vapor existing in a hypothetical column of atmosphere (this is measured in pr-μm, or micrometers of precipitable H2O) | ||

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Water density at Northern latitudes.jpg|200px|right||thumb|H2O column density at High Northern latitudes (think the “Arctic circle”) {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|10}}]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Planetary scientists have systematically recorded the density of atmospheric H2O column for the entire surface of Mars, compiling a global map of water vapor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford average Mars global water.jpg|200px|left||thumb| Seasonally averaged water vapor abundance (in um of precipitation) {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|9}}]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | From this map it becomes clear that, as on Earth, there are variations in the distribution of atmospheric water vapor based on longitude and latitude. In particular, the Northern hemisphere contains significantly more atmospheric H2O than the South. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As with dust, the distribution of water in the Martian environment represents a complex system which should be considered in the calculus of photosynthesis in the Martian colony. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==='''In Summary'''=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Considering all of these factors, it is apparent that modeling the productive capacity of photosynthesis on Mars is complex and requires parameters describing geophysical conditions and how cyanobacteria are affected by them. As planetary scientists continue to collect more observations about Mars, our understanding of the differences and similarities between their atmosphere and ours will grow. Then, exobiologists will be able to simulate more variables in the lab to study microbial physiology and identify challenges for synthetic biologists to solve through genetic engineering. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === '''References''' === | ||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|A|http://www.fao.org/docrep/w7241e/w7241e05.htm#1.2.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|1|http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/marsfact.html}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|2|http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/earthfact.html}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|3|de Vera, Jean-Pierre et al. (2010) Survival Potential and Photosynthetic Activity of Lichens Under Mars-Like Conditions: A Laboratory Study. ''Astrobiology'' 10 215-227.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|3_1|http://ccar.colorado.edu/asen5050/projects/projects_2001/benoit/solar_irradiance_on_mars.htm}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|3_2|http://www-mars.lmd.jussieu.fr/mars/time/solar_longitude.html}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|4|Li, KJ et al. (2010) Periodicity of Total Solar Irradiance. ''Solar Physics'' 267 295-303.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|5|Lemmon, MT et al. (2004)Atmospheric Imaging Results from the Mars Exploration Rovers: Spirit and Opportunity. ''Science'' 1753-1756.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|6|McCleese, DJ et al. (2010) Structure and dynamics of the Martian lowe and middle atmosphere as observed by the Mars Climate Sounder: Seasonal variations in zonal mean temperature, dust, and water ice aerosols. ''Journal of Geophysical Research'' 115 E12016.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|7|http://tes.asu.edu/}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|8|Barlow, Nadine. (2008) ''Mars: An Introduction to its Interior, Surface and Atmosphere.'' Cambridge University Press}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|9|Smith, MD. (2001)The annual cycle of water vapor on Mars as observed by the Thermal Emission Spectrometer. ''Journal of Geophysical Research'' 107 E11, 5115.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|10|Melchiorri, R et al. (2007)Water vapor mapping on Mars using OMEGA/Mars Express. ''Planetary and Space Science'' 55 333-342.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|11|Fouchet, T et al. (2007) Martian water vapor: Mars Express PFS/LW observations. ''Icarus''190 32-49}} | ||

{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Foot}} | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Foot}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:09, 29 September 2011

Photosynthesis and Mars

Photosynthesis on Earth represents an effective way of converting solar to chemical energy on a large scale. The theoretical maximum yield of photosynthesis is approximately 11% of solar energy, with a practical efficiency of 3-6%.A Added to the fact that this mechanism is robust (like all biological systems, photosynthetic organisms are self-replicating and self-repairing), photosynthesis would appear to be key for any energy generation purposes in an isolated, low-resource setting such as a Martian settlement.

Photosynthetic output depends on variables such as atmospheric composition and amount of accessible sunlight. In this section we introduce environmental conditions on Mars that need to be factored when assessing the usefulness of photosynthesis on Mars.

Atmosphere

The Martian atmosphere is strikingly similar to our own atmosphere on Earth; we share the top four components in atmospheric composition (N2, O2, Ar, and CO2), albeit in varying amounts. 1,2

| Mars | Earth |

| 6.36 mb pressure | 1014 mb pressure |

| Carbon dioxide 95.32% | Nitrogen 78.08% |

| Nitrogen 2.70% | Oxygen 20.95% |

| Argon 1.60% | Argon 9340 ppm |

| Oxygen 0.13% | Carbon dioxide 380 ppm |

| Carbon monoxide 0.08% | Neon 18.18 ppm |

Two main differences stand out: the atmosphere of Mars is overwhelmingly composed of CO2, and is much thinner than Earth's (0.6%)

Studies of lichen in Mars conditions suggest, however, that these differences may not be so bad.3 Photosynthetic activity is not diminished by a reduction to Mars atmospheric pressure (at least within the time frame of days). Furthermore, while Marslike levels of CO2 reduce photosynthetic activity by 60% (while keeping all other conditions within Earth ranges), the reduction to Mars pressure actually improves activity back to levels seen in wholly Earth conditions.

This would suggest that the atmospheric composition and density of Mars, although inhospitable to human survival, are not incompatible to photosynthesis.

Solar irradiance

A crucial factor to consider is the amount of solar energy available on Mars. Irradiance is a measure of how much solar radiation reaches a planet from the Sun, and is calculated from the length of the day-night cycle, distance from the Sun, position of orbit, etc. 3_1

Based on this method, solar irradiance at the mean distance between Mars and the Sun reaches a theoretical maximum of 590W/m2 (assuming no distorting effects from the Martian atmosphere).

As a point of comparison, solar irradiance for Earth (measured from satellite instrumentation above the atmosphere) is approximately 1360W/m2 4. This means that Mars, which is 1.52 times as far from the Sun as Earth, receives 43% as much solar radiation per m2.

To achieve a more meaningful measure of irradiance for photosynthesis, however, we have to account for filtering in the atmosphere before solar rays reach the Martian surface.

Particulates in the Martian atmosphere

Dust is a huge part of the Martian environment on a local and global scale! Particulate matter in the atmosphere can have a dramatic impact on the amount of sunlight reaching the Martian surface. For a vivid example, look at the decreasing visibility in this surface view from the NASA Opportunity rover amidst a brewing dust storm. Were this kind of disruption sustained for too long, any settlement or machine wholly dependent on solar energy would fail.

τ (greek tau) stands for optical density, which is a measure of how transparent the atmosphere is. τ = 0 represents perfect transparency

Excluding the effect of regional storms, which interfere with sunlight in a temporary but unpredictable way, there are other dust dynamics we can consider as more constant.

Using ground measurements taken by NASA rovers over time, we know that the visible optical depth of the Martian atmosphere is τ = 0.9 [5] Put another way, this means that typically around 10^(-0.9) or 13%, of incoming sunlight is not scattered or absorbed before it hits the Martian surface.

Recent data gathered from satellites such as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) have begun to shed more light on the distribution and layering of dust. In particular, the MRO is able to take vertical profiles in addition to top-down images, offering a three-dimensional view6.

From satellite imagery, researchers have also compiled maps showing the overall geographical distribution of dust coverage over a sample two-week span. 7 Global dust patterns are a complex phenomenon, but must be considered in the placement of systems utilizing photosynthesis.

Temperature

The temperature on Mars is an obvious factor in considering the viability of microorganisms brought to the planet surface. Thermal emission spectrometry readings have been very thorough in generating a global map of temperatures. Temperature varies greatly between geographical location, altitude, and day/night, although as a whole the planet is significantly colder than Earth. Nonetheless, there are broad regions (especially in the intermediate latitudes) which experience temperatures comfortable for Earth life.

Although any humans will obviously require extensive environmental protection due to temperature and a whole host of other factors, it seems that temperature does not necessarily preclude microbes from surviving on Mars.

H2O Content

As photosynthesis is a water-dependent process, the distribution of water on Mars is of interest. Enormous quantities of H2O are contained in the polar ice caps; the southern ice cap would submerge the entire planet in 11 meters of water if melted.

Geographical features on the Martian surface suggest water erosion in quantities far greater than can be accounted for by ice in the polar regions.8 For this reason, scientists hypothesize large amounts of ground ice and subsurface reservoirs exist across the planet. Though there are no comprehensive surveys of subsurface water deposits, there have been numerous studies of yet another source.

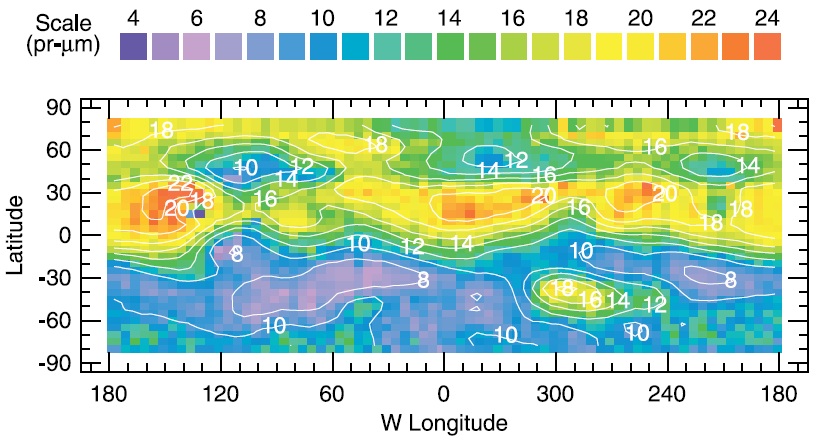

Vapor content has been measured from several satellites orbiting Mars.9,10,11 Cameras circling above use spectrometers to image the planet and note the intensity of peaks at certain wavelengths corresponding to H2O. From this information, they can quantify the amount of water vapor existing in a hypothetical column of atmosphere (this is measured in pr-μm, or micrometers of precipitable H2O)

Planetary scientists have systematically recorded the density of atmospheric H2O column for the entire surface of Mars, compiling a global map of water vapor.

From this map it becomes clear that, as on Earth, there are variations in the distribution of atmospheric water vapor based on longitude and latitude. In particular, the Northern hemisphere contains significantly more atmospheric H2O than the South.

As with dust, the distribution of water in the Martian environment represents a complex system which should be considered in the calculus of photosynthesis in the Martian colony.

In Summary

Considering all of these factors, it is apparent that modeling the productive capacity of photosynthesis on Mars is complex and requires parameters describing geophysical conditions and how cyanobacteria are affected by them. As planetary scientists continue to collect more observations about Mars, our understanding of the differences and similarities between their atmosphere and ours will grow. Then, exobiologists will be able to simulate more variables in the lab to study microbial physiology and identify challenges for synthetic biologists to solve through genetic engineering.

References

A http://www.fao.org/docrep/w7241e/w7241e05.htm#1.2.1

1 http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/marsfact.html

2 http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/earthfact.html

3 de Vera, Jean-Pierre et al. (2010) Survival Potential and Photosynthetic Activity of Lichens Under Mars-Like Conditions: A Laboratory Study. Astrobiology 10 215-227.

3_1 http://ccar.colorado.edu/asen5050/projects/projects_2001/benoit/solar_irradiance_on_mars.htm

3_2 http://www-mars.lmd.jussieu.fr/mars/time/solar_longitude.html

4 Li, KJ et al. (2010) Periodicity of Total Solar Irradiance. Solar Physics 267 295-303.

5 Lemmon, MT et al. (2004)Atmospheric Imaging Results from the Mars Exploration Rovers: Spirit and Opportunity. Science 1753-1756.

6 McCleese, DJ et al. (2010) Structure and dynamics of the Martian lowe and middle atmosphere as observed by the Mars Climate Sounder: Seasonal variations in zonal mean temperature, dust, and water ice aerosols. Journal of Geophysical Research 115 E12016.

8 Barlow, Nadine. (2008) Mars: An Introduction to its Interior, Surface and Atmosphere. Cambridge University Press

9 Smith, MD. (2001)The annual cycle of water vapor on Mars as observed by the Thermal Emission Spectrometer. Journal of Geophysical Research 107 E11, 5115.

10 Melchiorri, R et al. (2007)Water vapor mapping on Mars using OMEGA/Mars Express. Planetary and Space Science 55 333-342.

11 Fouchet, T et al. (2007) Martian water vapor: Mars Express PFS/LW observations. Icarus190 32-49

"

"