Team:Brown-Stanford/REGObricks/Biobrick

From 2011.igem.org

Biobrick2

Research and acquisition

In June, we conducted background research on Sporosarcina pasteurii and it’s ureolytic ability. In these preliminary searches, we learned that the urease cassette of S. pasteurii, responsible for the organism’s ureolysis and biocementation capabilities, had already been the subject of some cloning and transformations experiments involving E. coli. 1,2,3

We contacted all of these investigators to learn the status of their current research in this area and to learn more about the urease cassette; unfortunately, many of these researchers were based in South Korea, and we never received a response to our inquires. Their research papers were similarly inaccesable on the internet. We lucked out when we contacted [http://ssbang.sdsmt.edu/ Dr. Sookie Bang] of the South Dakota School of Mining and Technology, however. Her lab had developed a number experiments studying microbially-induced calcite precipitation of both S. pasteurii and recombinant E. coli, and still kept active strains of both. She and her graduate student, Terran Bergdale, generously sent us a plate of both S. pasteurii and HB101/pBU11 E.coli, and provided us with wonderful advice and information throughout the entire summer. The E. coli strain we were sent had been transformed with a plasmid containing the urease cassette of S. pasteurii and standard backbone pBR322. The sequence of pBR322 is freely available in many online databases, but the exact sequence of the urease cassette was unknown. As previously stated, we were unable to find or access the scientific literature that detailed the sequence or genes within the cassette. The only information we were able to obtain from inquired and research was that the cassette itself was approximately 10.7 kb long, and was inserted into the HindIII restriction site of plasmid backbone pBR322.

Sequencing

We spent many hours searching for the sequence in online databases; our search on NCBI yielded 3 distinct urease operons, none of which were the size of our cassette. Furthermore, we found few possible patterns of overlap among those NCBI results to predict a construct of 10.7 kb. In the end we decided to pursue sequencing the construct sent to us. We were lucky enough to have met members of [http://physiology.med.cornell.edu/faculty/mason/lab/ the Mason Lab] of the Weill-Cornell Medical College earlier who generously offered to sequence the urease construct with their PacBio high-throughput sequencing platform. We graciously accepted and sent off copies of the original pBU11 plasmid for sequencing, but due to unforseen circumstances and poor luck we have not yet been able to obtain the sequence. We hope to have the sequence data by the Jamboree in Indiana, and we that we will be able to include them in our presentation!

Biobricking of Urease Cassette

Primer Design - To clone the urease cassette out of pBR322 and modify it into a biobrick part, we designed sequence primers that would anneal to the template DNA but maintain an unbound DNA “tail” containing the appropriate restriction site sequences (E, X, S, P) for that end of the operon. EcoRI and XbaI were built into the forward primer, SpeI, PstI into the reverse; the sequence of both these primers can be found in our primer reference book here. Because we did not know the sequence of the urease cassette, deigning primers for the sequence would have been guesswork. Instead, we deigned the primers to anneal to the sequences of pBR322 that made up both sides of the pBR322 HindIII cut site, into which the urease cassette had presumably been ligated. While this approach ultimately allowed us to biobrick a functional urease cassette form S. pasteurii, the primers we designed were not optimal. First, the primers added approximately 30 bases each on either side of the cassette that were not originally part of the S. pasteurii operon, and these additions could have been avoided by previous knowledge of the sequence. Second, our primers included either side of the original pBR322 HindIII cutsite. In our characterization, we will determine whether this cut site was preserved in our biobrick and if it possible to cut our biobrick with HindIII.

HB101/pBU11 - In order to clone out the urease cassette, we grew up, plated, and put in cryostock the HB101/pBU11 E. coli that we were sent by the Bang lab. Liquid cultures and plates were composed of Team:Brown-Stanford/Lab/Protocols/LB and ampicillin, to which pBR322 confers resistance.

PCR - We used Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Kit to develop a successful PCR amplification protocol for the urease cassette template. Because of the length of the desired sequence, we needed a polymerase capable of both long read length and high fidelity, which were both provided by the Phusion® kit.

The gel image to the right represents a successful PCR amplification of the urease cassette insert of pUB11 using our edited Phusion PCR protocol. The leftmost lane depicts a 1 kb ladder, and all lanes to the right of the ladder are PCR product. In each lane, the topmost band represents template plasmid (~15.1 kb), and the second band represents successfully amplified urease construct (~10.8 kb). A negative control had been performed on another PCR/gel verification protocol in parallel with the above workflow.

We then performed PCR purification with the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System to prepare the samples for restriction digest.

Restriction digest - Because we had no information concerning the urease cassette, we had no idea if any of the four standard biobrick restriction sites were present in its sequence. Therefore, we attempted our restriction digest protocol in a random fashion, beginning with XbaI and PstI cuts: The gel above represents XbaI, PstI digests of plasmid pSCB1C3 (lane 3) and of our urease construct/PCR product (lane 4). Lanes 1 and 5 display 1 kb ladders; the last two lanes are spurious data.

XbaI, PstI restriction digests fragmented the urease cassette into four distinct bands at ~2.25, ~2.75, ~3, and ~4kb. These data suggest that at least two XbaI or PstI cut sites are present in the urease cassette itself, though it is difficult to locate them exactly as the digested results do not total the expected 10.8 kb. Later it was determined that the Pstl was responsible for the fragmentation displayed in the above image. We conducted the same restriction digest protocol with XbaI, SpeI enzymes. The resulting product was much more encouraging as a single band still remained, at the same relative length as our urease construct. To test our restriction protocol, we again ran the same digest of pSB1C3 in parallel.

Because the urease construct does not seem to have diminished in size, and because there seems to only a single, strong band of a significant length, we assumed that both XbaI and SpeI were cutting only at their prescribed cut sites near the ends of the construct. It is possible that the restriction enzymes may cut inside the construct’s biobrick ends, theirin excising one half of the biobrick cut sites. Once sequencing is accomplished we will be able to determine if our digests was successful at preserving the biobrick ends of the construct. The restriction protocol for the products above are available in our Protocols section.

Gel Extraction - The XbaI, SpeI digests of both pSB1C3 and our urease construct were run through agarose gel through gel electrophoresis. Gel extraction was performed with the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up kit and protocol

Ligation - We ligated our urease contruct with pSB1C3 plasmid backbone using T4 DNA ligation protocol.

Transformation - Transformation of E. coli with our urease construct/pSCB3 (part BBa_K656013) was conducted using NEB's NEB 5-alpha Competent E. coli (High Efficiency) protocol. Transformant cells were plated on LB-chlor plates and allowed to grow overnight. Colonies were sampled at random, and tested for ureolytic activity.

Characterization

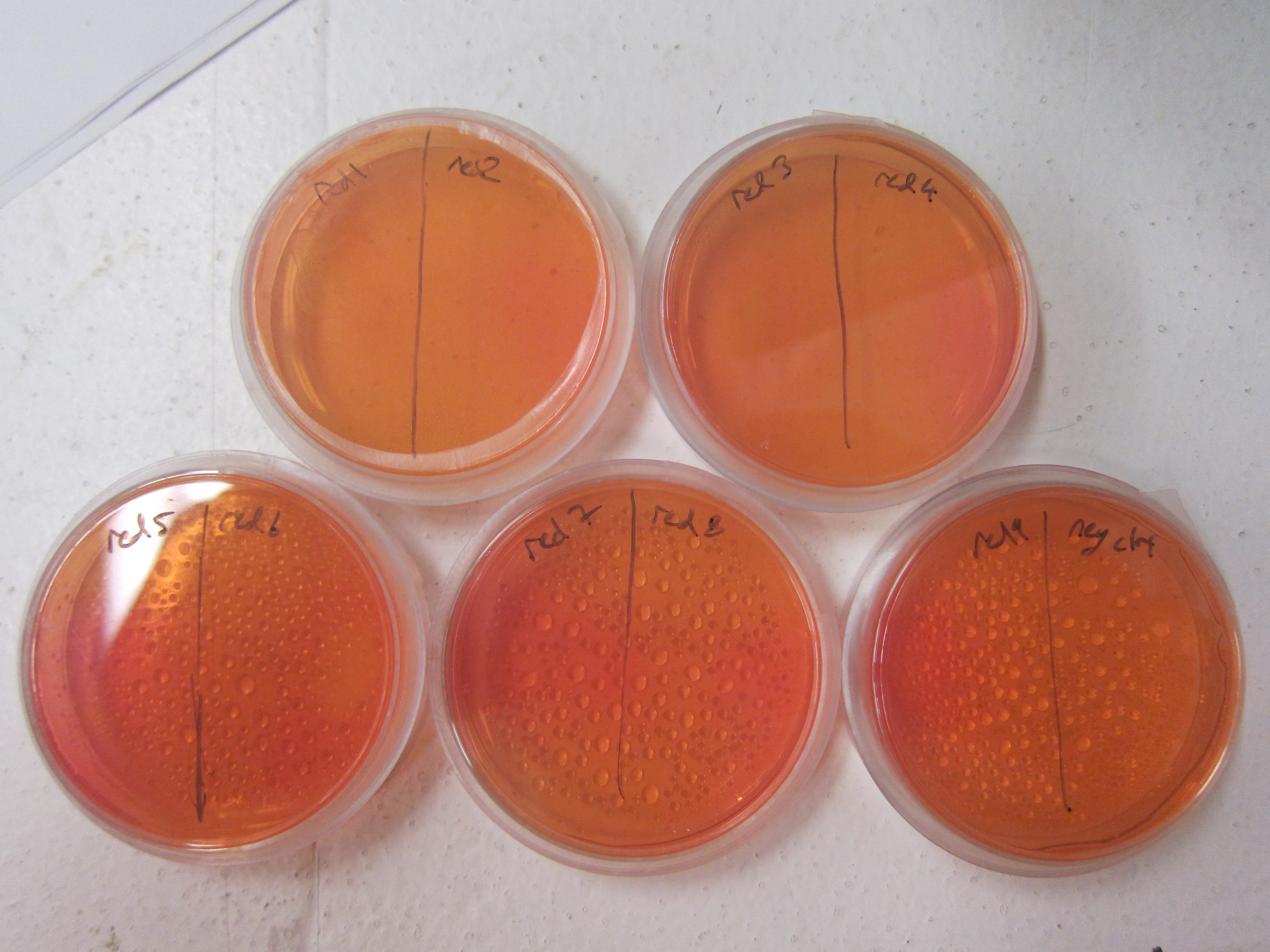

As a qualitative assay of urease activity, we selected transformant colonies at random from the LB-Chlor growth plates and grew them up in liquid LB-Chlor culture. These monoclonal cultures were then plated and allowed to grow on urease test plates. These plates contained a large amount of urea, some basic salts, and phenol-red pH indicator dye. Their pH was carefully calibrated to 6.8; if urease was present and active in the cultures, the urea would be cleaved in the surrounding agar, causing the pH of the surrounding agar to increase. Phenol-red would then indicate the subsequent increase in pH from ureolysis. All but one of the colonies we selected off the LB-Chlor plate exhibited ureolytic activity, indicating that our workflow had resulted in the construction of a functional S. pasteurii urease biobrick. From the urease test plates, the ingredients of which can be found in the Protocols section, we were able to determine that our part did in fact, function, albeit quantitatively. To more accurately and quantitatively measure the activity of the urease biobrick, we performed the conductivity protocol as outlined in our Protocols section.

References

1 Kim, S.D. and Hausinger, R.P. (1994) Genetic organization of the recombinant Bacillus pasteurii urease genes expressed in Escherichia coli. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 4: 108-112.

2 You, J.H., Kim, J.G., Song, B.H., Lee, M.H. and Kim, S.D. (1995) Genetic organization and nucleotide sequence of the ure gene cluster in Bacillus pasteurii. Molecular Cells 5: 359-369.

3 Bang, S.S. and Ramakrishnan, V. (S.S. Bang, J.K. Galinat and V. Ramakrishnan, Calcite precipitation induced by polyurethane-immobilized Bacillus pasteurii. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 28 4 (2001), pp. 404–409.

"

"