Team:Amsterdam/Labwork/Characterization

From 2011.igem.org

Characterisation

Our CryoBricks are designed to facilitate cold resistance in E. coli. We characterise this cold resistance in two different ways.

The first characterisation method involves measuring freeze/thaw cycle survival rate. We alternatingly expose E. coli (in liquid culture) to freezing and thawing. After each thaw step, part of the culture is plated out, and after ~15 hours at 37°C, colony forming units (CFUs) were counted on the plates. These CFUs represent the number of viable cells present in the culture. Cold resistant cells will have a higher fraction of cells surviving each cycle. The protocol followed for these experiments can be found on this page.

The second method through which we characterise cold resistance is more relevant to most of our foreseen applications. It involves measuring the effect of expressing a CryoBrick on the specific growth rate (μ) of an organism, at temperatures suboptimal for growth. For normal E. coli, μ peaks at 37°C, making any temperature lower than this suboptimal. The rate at which μ declines when temperatures drop below this optimum is an indication of cold resistance, as more cold resistant E. coli will be able to maintain a higher μ at low temperatures.

μ is defined as the increase of biomass per unit of time, per unit of biomass, and as such, it can be estimated from time-series data of a logistically growing population's density. To characterise the effect of CryoBrick expression on growth at suboptimal temperatures, we measure growth curves of E. coli equipped with a (combination of) CryoBrick(s) at different temperatures. The culture's optical density at a wavelength of 600nm (OD600) is used as an indicator of population density, and measuring this at frequent time intervals during culture growth results in the aforementioned curve. The protocol used to obtain this data can be found here. Subsequent analysis of the data, including how μ is estimated, is explained on the data analysis page.

Results

At the time of this writing, two of the designed CryoBricks have been characterised, with both characterisation methods. The first is [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K538000 BBa_K538000], encoding Cpn10. It was expressed in E. coli through part [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K538200 BBa_K538200]: a protein generator under control of the Lac operon's promoter, incorporating one of the stronger Community Collection RBSes ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034]). The generator was transformed into the Top10 strain, which is LacI deficient. As such, the part should be expressed constitutively, and no IPTG or lactose is needed to activate expression. Note that Cpn10 has only ever been reported to be functional when coexpressed with its partner protein Cpn60, so we expected it not to have any influence on cold resistance at all.

The second CryoBrick we've succesfully characterised is [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K538004 BBa_K538004]: Polaribacter irgensii 's CspC protein, expressed in our bacteria through [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K538204 BBa_K538204], which only differs from the Cpn10 generator in that it contains the CspC coding region instead. This protein has been reported to strongly increase the freeze/thaw cycle survival rate of E. coli,[http://www.springerlink.com/content/qr2q5722j0t78653.pdf] so we expected to reproduce this observation. We had no particularly strong prior expectations about this enzyme influencing growth rate at suboptimal temperatures, as nothing of the sort has been reported in literature to date.

Freeze/Thaw Cycle Survival

Two separate freeze/thaw cycle survival measurements confirmed the literature statement that expression of CspC will increase E. coli 's chances of surviving freezing and thawing. The first experiment already demonstrated this through three strains - comprising a Cpn10 generator, a CspC generator, or an empty vector - measured in triplo for three cycles. Unfortunately, the initial cell count - to which subsequent measurements are normalized in determining the percentage of surviving cells - was only based on a single plate per strain, and the CspC strain's count was ~4 times as high as that of the other two strains.

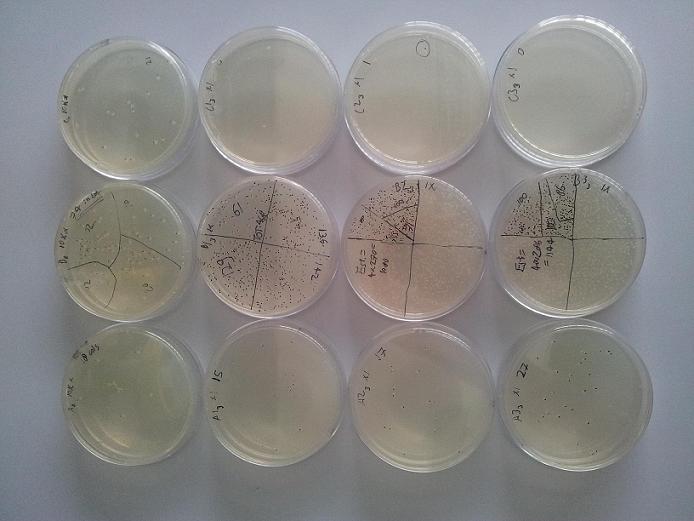

Still, interesting observations were made during this experiment. Disregarding the inaccurate first measurement, the percentage of colony forming units (CFUs) that survived was calculated between cycles 2 and 3 instead of cycles 0 and 3. As can be seen in figure 1 below, between the three control plates (top row), there was only a single colony left after a third freeze/thaw cycle, which is effectively 0% of the CFUs making it to the second freeze/thaw cycle. The cells expressing CspC, on the contrary, maintained 90% of the CFU count from cycle 2 in cycle 3. A remarkable observation is that Cpn10 also, on average, maintained 30% of the CFUs counted in cycle 2. This suggests it retains a degree of functionality in absence of Cpn60.

If the observation that Cpn10 influences E. coli 's ability to survive freeze/thaw cycles in absence of Cpn60 can be reproduced, this constitutes an interesting discovery. Cpn60 has already been reported to function in absence of Cpn10.[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1138217/pdf/biochemj00085-0050.pdf] However, to the best of our knowledge, the reverse - Cpn10 functioning in absence of Cpn60 - has never been reported. Based on structural analysis, it has been suggested the Cpn10 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis can bind substrates in absence of Cpn60,[http://jb.asm.org/cgi/reprint/185/14/4172.pdf] but demonstrating the Cpn10 of Oleispira antarctica can enhance the cold resistance of E. coli in absence of Cpn60 would be a steady step towards validating this otherwise unconfirmed suggestion.

Following our first experiment, it was decided to try to quantitatively characterise the cold resistance granted by CspC expression more accurately. Quadrupple cultures of cells expressing CspC, and the same amount of cultures comprising empty control vectors, were exposed to three freeze/thaw cycles as with the first experiment. This time, initial cell count was determined in quadruplo instead of in singulo. Subsequent CFU counts were normalized to fractions by division through their respective culture's initial cell count, and the calculated cell survival rates are plotted below. (Figure 2)

From the figure above, it can be concluded expression of CspC really does improve the freeze/thaw cycle survival rate of E. coli. At the time of this writing, a similar experiment is being carried out with cultures expressing Cpn10, in an attempt to reproduce its unexpected positive result from the first experiment. We hope to present these results at the regional (and global) Jamboree(s)!

Growth at Suboptimal Temperatures

The growth of 4 different strains was measured at 7 different temperatures. A wildtype strain, a strain comprising an empty vector (with an antibiotic resistance, but no CryoBrick coding regions), and strains equipped with either the Cpn10 generator ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K538200 BBa_K538200]) or the CspC generator ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K538204 BBa_K538204]) were cultured at 4, 8, 15, 21, 25, 30 and 37°C. If expression of a CryoBrick influences growth rate at any of these temperatures, we expect the effect to be strongest at the lower temperatures. Conversely, as the plasmids shouldn't hinder cell growth in optimal circumstances, no differences are expected at 37°C. The results of our growth rate characterisation experiments are displayed in figure 3, below.

Conclusion

Figure 3 shows that, in accordance with our expectations, expression of Cpn10 does not significantly influence growth rates at suboptimal temperatures, at least in the concentration at which it's expressed through this construct. No real expectations existed regarding CpsC 's influence on these growth rates, and apparently, expression of this CryoBrick doesn't allow E. coli to maintain higher growth rates at suboptimal temperatures either.

We have, however, confirmed that the CspC CryoBrick is functional, and that it influences the freeze/thaw cycle survival of E. coli, as we expected it to based on literature. (Figure 2) Of particular interest is that preliminary data suggests expression of Cpn10 alone can enhance cold resistance. It doesn't appear to be as efficient as CspC when it comes to increasing freeze/thaw survival, but nevertheless; should follow-up experiments fail to contradict this initial finding, it is to the best of our knowledge the first time Cpn10 has been demonstrated to significantly affect E. coli in absence of its partner protein, Cpn60.

References

- Uh et al. Rescue of a Cold-Sensitive Mutant at Low Temperatures by Cold Shock Proteins from Polaribcater irgensii KOPRI 22228 J. Microbiol. 48, 798-802 (2010)

- Staniforth, Burston, Atkinson & Clark Affinity of chaperonin-60 for a protein substrate and its modulation by nucleotides and chaperonin-10. Biochem J. 300 (3), 651-658 (1994)

- Robberts et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis chaperonin 10 heptamers self-associate through their biologically active loops. J. Bacteriol. 185, 4172-4185 (2003)

"

"