Team:Brown-Stanford/PowerCell/NutrientSecretion

From 2011.igem.org

Nutrient Secretion and Utilization

PowerCell is the generator that will power all of the BioTools in a Martian settlement. PowerCell will secrete nutrients for use by other biological tools a source of energy and raw materials to construct useful products.

Like any other tools, biological tools need energy to run and raw materials to work with. The two major nutrient sources needed for biological tools are carbon sources (sugars) and nitrogenous nutrients (ammonia). In a Martian settlement, PowerCell will harness the energy of the sun to harvest these nutrients directly from the atmosphere and provide them to the settlement's biological tools.

This summer, we tackled only the half involving sugar secretion. This was partially to due to the time constraints of a summer project, and partially because there is evidence that ammonia secretion occurs in cyanobacteria by means of passive diffusion without the need for genetic tinkering ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378109791906924 Ammonia translocation in cyanobacteria]). More research needs to be done to determine if this level of diffusion is sufficient to sustain other biological tools. In any case, we designed our system on a platform (Anabaena 7120) with the capability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, so that this avenue is open for exploration in the future.

Sucrose

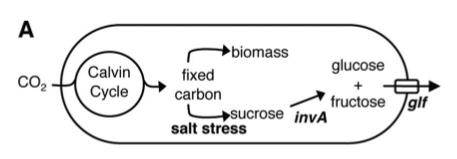

The sugar we chose to secrete is sucrose. The major inspiration for our project was the paper [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/76/11/3462 Engineering Cyanobacteria To Synthesize and Export Hydrophilic Products]. This work was done in Dr. Pamela Silver's lab, and describes a glucose/fructose secretion device, achieved in the single-celled bacterium S. elongatus.

In a nutshell, S. elongatus were forced under salt stress to produce sucrose, which was broken down into glucose and fructose by the glf enzyme, then transported out of the cell by the invA transporter.

At the Fifth International Conference on Synthetic Biology, SB5.0, we spoke with a member of Dr. Silver's lab, Danny Ducat. He advised us that one of the problems with the glucose/fructose secretion system is its low yield. He suspected that because glucose and fructose are directly metabolizable by the cell, much of these sugars are consumed by the cell before they ever have a chance to be secreted. For this reason, it may be better to directly secrete sucrose, which is not metabolizable by the cell, and worry about breaking it down later. This is what we did, although the choice does have some ramifications.

Because E. coli is the a primary host species for genetic modification, it is likely that many biological tools for space exploration will be designed in E. coli. The most common laboratory strains of E. coli , TOP10 and K12, cannot directly metabolize sucrose. For this reason, they cannot make use of PowerCell's output directly. In order to utilize this output, sucrose will need to be broken down into glucose and fructose , or biological tools that intend to utilize PowerCell should be hosted by a strain that can directly metabolize sucrose. E. coli W is a safe and easily transformable laboratory strain with this ability, and, as outlined in [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/12/9#IDAJ1FOQ The genome sequence of E. coli W (ATCC 9637): comparative genome analysis and an improved genome-scale reconstruction of E. coli], may confer some other advantages to biological tools to be used in space, including including fast growth, stress tolerance, growth to high cell densities. Furthermore, there is some indication that sucrose as a feedstock can confer other benefits, such as oxidative, heat, and acid stress ([http://www.springerlink.com/content/b80870618103w67l/ Development of sucrose-utilizing Escherichia coli K-12 strain by cloning β-fructofuranosidases and its application for l-threonine production]).

PowerCell Contruct Design

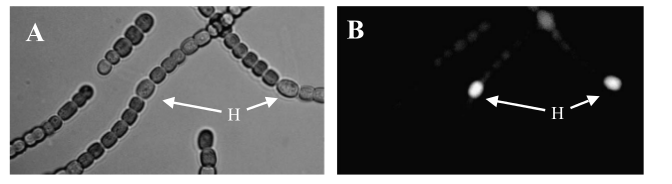

We wanted to isolate sucrose secretion to just vegetative cells, as heterocysts do not participate in production of sucrose through photosynthesis. A similar cell-type-specific gene expression was was achieved in [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167701204001745 Construction and use of GFP reporter vectors for analysis of cell-type-specific gene expression in Nostoc punctiforme]. Arguetta et al. confined expression of a fluorescent marker to only vegetative cells in a similar filamentous diazotrophic cyanobacterium, Nostoc Punctiforme. They placed the GFP gene behind a promoter present in the Photosystem I of Nostoc punctiforme, psaC. This way, GFP expression was only turned on in photosynthesizing cells, and not in heterocysts. They did not know the exact sequence of the psaC promoter, so they just took the 400 base pairs upstream of the psaC gene as a unit containing the promoter. We have done similarly to isolate the psaC promoter from Anabaena 7120. Below is an image showing cell-type-specific GFP expression achieved in the paper.

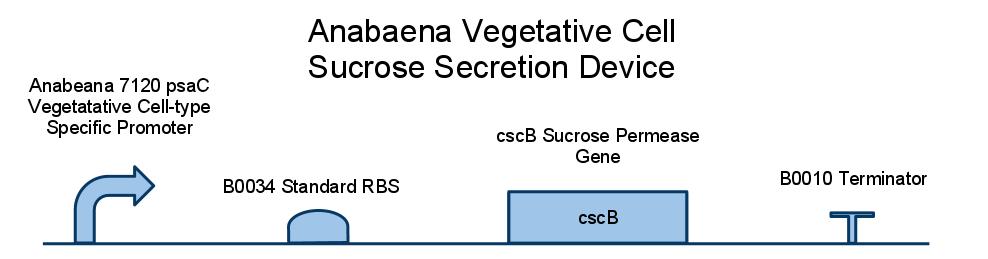

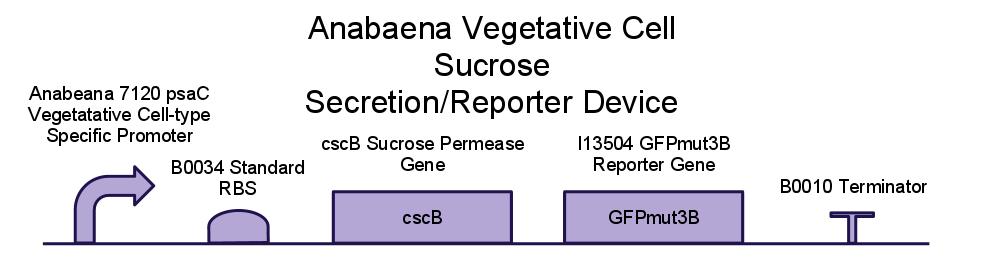

We placed a sucrose symporter gene, cscB, behind our Anabaena 7120 psaC promoter in order to confine sucrose secretion to only vegetative cells. Registry standard RBSes and terminators were used for ease of assembly and compatibility. Below is a diagram of our sucrose secretion device. A discussion of the inner workings of the cscB gene can be found in [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006291X85714490 Active Transport by the CscB Permease in Escherichia coli K-12].

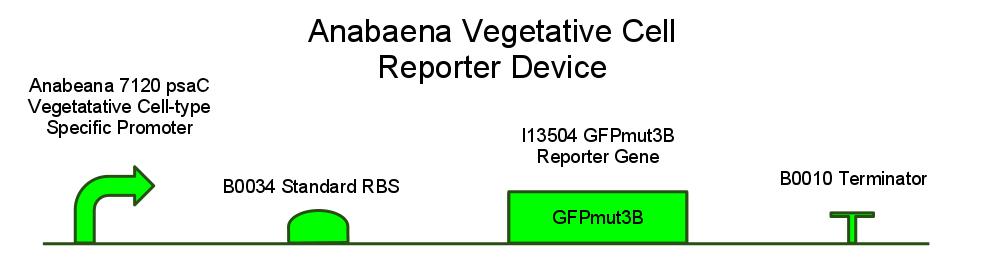

We have also created several other constructs containing GFP for debugging purposes. We used a modified version of GFP, GFPmut3B because normal florescence markers are easily lost among background chlorophyll pigments in cyanobacteria ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2860132/ Design and characterization of molecular tools for a Synthetic Biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology]).

Tranformation into Anabaena 7120

Cyanobacterial transformation can be difficult.

There are cyanobacteria which will accept DNA without complaint. Many model cyanobacterium species, such as Synechococcus elongatus or Synechocystis PCC6803, for example, will simply take up naked DNA in solution and express it.

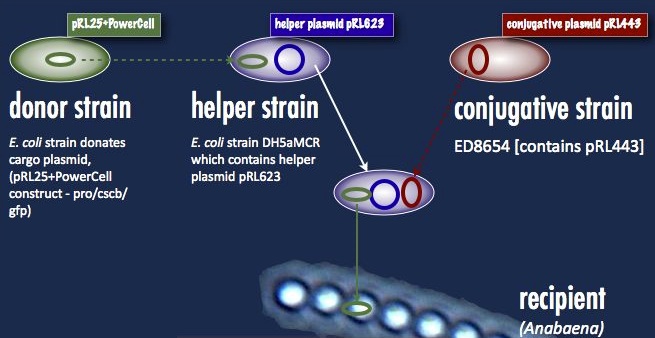

Anabaena 7120, on the other hand, must take its DNA through a rather circuitous path; the DNA construct must first be placed in a cargo plasmid and transformed into E. coli by traditional means. Transfer to Anabaena takes place by conjugation, facilitated by a second E. coli strain carrying a plasmid encoding the machinery for bacterial conjugation.

Another problem is the propensity of Anabaena to slice and dice foreign DNA with isoschizomers of the restriction enzymes AvaI, AvaII and AvaIII. This has been addressed with methyltransferases targeting the same sequences; that means a third E. coli strain carrying these methyltransferases (a helper plasmid) participates in the conjugation. At the end of all this, a certain number of cyanobacterial cells take up the DNA, and are selected for with neomycin on minimal media. As soon as the unsuccessful exconjugates and the bacterial parental strains die off, transformant colonies can be picked. One significant hindrance associated with this process is the slow cyanobacterial doubling time; the transformants can take upwards of a week to grow.

Our first trials were performed with the helper plasmid pDS4101, the conjugative plasmid pRL443 and the cargo plasmid pRL25. pDS4101 does not possess the methyltransferases which can epigenetically protect the incoming DNA from restriction, and so can only be used to transfer plasmids lacking restriction sites, such as pRL25, as a proof of concept.

Towards the end of the summer we were able to obtain the helper plasmid pRL623 containing the three methyltransferases which together offer complete protection from restriction inside Anabaena. There was an added obstacle to this new route, however: pRL623 can only be carried against certain E. coli genetic backgrounds lacking methyl-restricting enzymes, in order to prevent restriction of the host genome. This meant that transfer of the helper plasmid into the cargo plasmid strain before conjugation into Anabaena results in the suicide of that cargo strain, and no transformation. The solution to this was transformation by more traditional means of the cargo plasmid into the strain already carrying the helper plasmid; the cargo was then be delivered into Anabaena without transfer of the dangerous helper plasmid, and the helper plasmid had its opportunity to protectively methylate the cargo prior to transformation.

We are sincerely grateful to Dr. Jeff Elhai (Virginia Commonwealth University), Dr. Peter Wolk (Michigan State University), James Golden (University of California, San Diego) for their crucial help and guidance with cyanobacterial transformation.

PowerCell Transformation

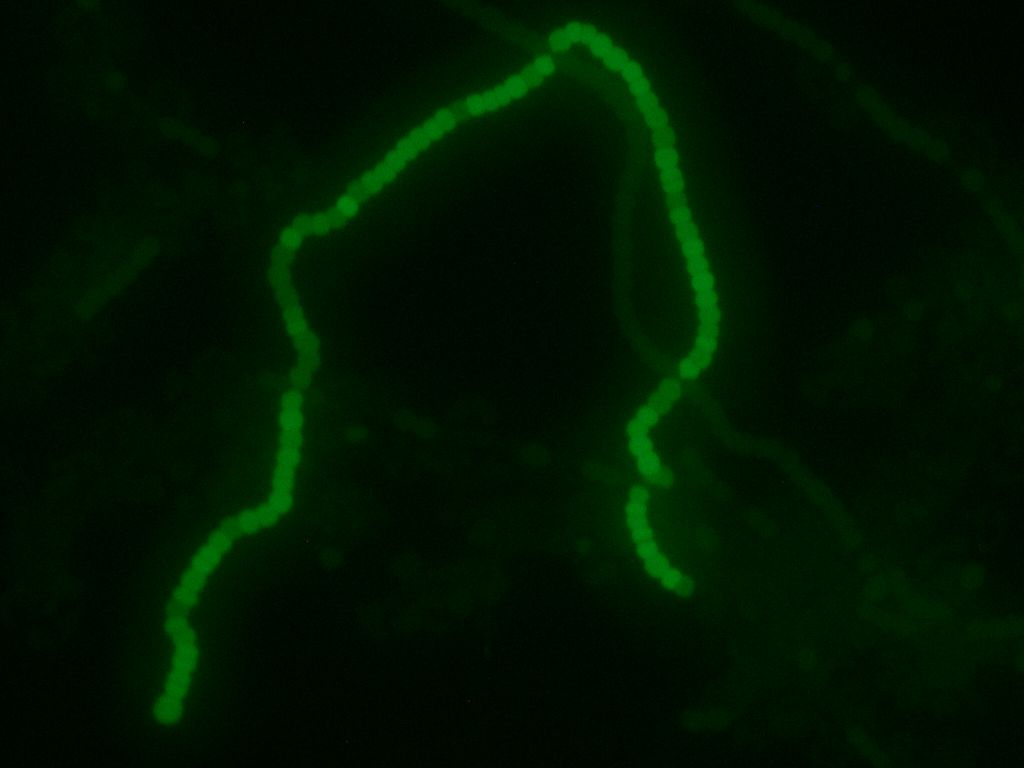

We transformed the final PowerCell construct into Anabeana using the methods described above. Expression of GFP is clearly visible, indicating the transformation was successful. Some non-transformants can be seen in the background.

We selected for our transformants using neomycin, and let the cultures grow.

The initial selection looked promising. The left-most culture tube contains BG11(N-) w/o neomycin selection + 50µl of the original conjugation mixture. Both transformed and untransformed Anabaena should be able to grow in this mixture. As expected, this culture tube has the highest cell density. The middle culture tube contains BG11(N-) with neomycin + 50µl of the original conjugation mixture. Only Anabaena containing our plasmid should be able to grow in this mixture. As desired, growth is still visible, but is less dense. The right-most tube contains BG11(N-) with neomycin + 50µl of WT Anabaena. Nothing should be able to grow here. As expected, everything in this tube is dead.

After about 2 weeks of growth, we can confirm the correct regulation of our sugar secretion construct by our pSac promoter by observing the presence of the GFP reporter. GFP expression is on in vegetative cells, and off in heterocysts, which implies that the sugar secretion construct is only active in vegetative cells, as we desire. Work is currently underway to assay the sucrose concentrations that are generated by our construct. We hope that these concentrations will be high enough to support growth of E. coli W; our experiments suggest the minimum concentration is around 5 mM (see section below). If the concentrations are high enough, we intend to grow E. coli W hosting several arbitrary active BioBrick plasmids, to show that PowerCell can power general biological tools. Updates will be posted here as they become available!

Transformed Anabaena showing cell-type specific GFP fluorescence under the control of the pSac promoter. GFP expression is on in vegetative cells, off in heterocysts. Some background fluorescence from chlorophyll is visible.

Utilizing sucrose from PowerCell

E. coli W

An essential aspect of the PowerCell project lies in microorganisms being able to survive off the nutrients being secreted by our genetically engineered Anabaena. Our carbon source, sucrose, is a disaccharide that is not necessarily able to be metabolized by all species.

Here our project intersects with current trends of bioproduction on Earth; sucrose is a cheap and easily obtained sugar, so there is interest in engineerable strains of microorganisms able to survive on it as a sole carbon source.

We came across research suggesting that E. coli W is one such promising strain. It is one of the few strains of non-pathogenic E. coli able to metabolize sucrose, has good tolerance for environmental stresses, and grows rapidly. (Archer 2011) There have been papers describing the process of adapting E. coli W as a bioreactor organism, and methods of growing them to high density and productivity using fed-batch cultures. (Lee 1993, Lee 1997).

In fact, the strain has already been used to produce a number of useful products. These include D(-)-lactate, a precursor to the formation of certain biodegradable plastic polymers, and L-alanine, a food additive and nutritional supplement. (Shukla 2004, Zhang 2007) With these examples, it is not difficult to imagine the production role of E. coli W in our Martian colony.

E. coli W Sucrose Metabolism Experiment

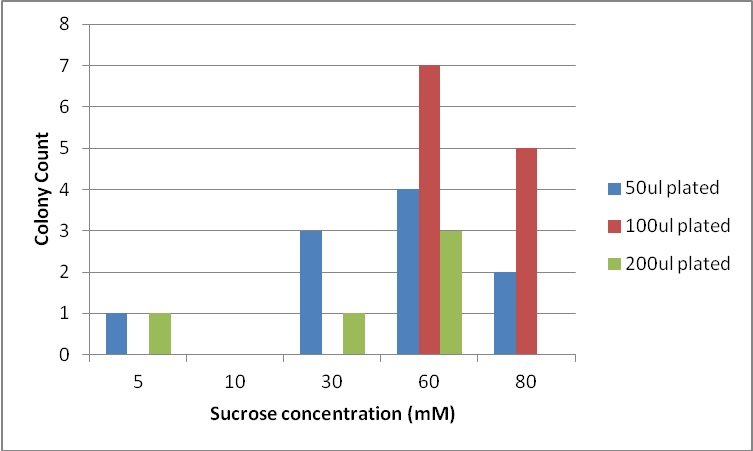

In the application of our project, PowerCell would grow alongside and support a productive microorganism strain such as E. coli W. We were thus interested in seeing whether E. coli W could grow in the conditions generated by PowerCell. This meant culturing on minimal BG-11 media with added sucrose to simulate secretion by Anabaena.

Based on literature (Niederholtmeyer, et al,2010) and correspondence with Mr. Ducat, we predicted that our Anabaena culture would produce no more than 8mM of sucrose. It would be difficult to support substantial E. coli growth on such low levels without a means of concentrating sugar via in the bioreactor design.

Initially we attempted to compare growth on BG-11 + sucrose with liquid cultures. However, multiple attempts yielded no appreciable change in O.D. after several days of incubation. We suspect that this was because E. coli growth was too small to detect via spectrophotometer.

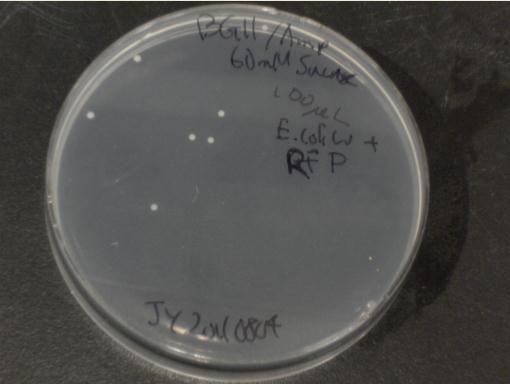

Next, we moved to agar plates as a more sensitive means of detecting cell growth. E. coli W with Amp resistance were grown, washed and resuspended in PBS to eliminate residual LB media, and streaked them on BG-11 Amp+ plates with varying concentrations of sugar (5mM, 10mM, 30mM, 60mM, and 80mM).

The cells were incubated at 37C and observed regularly before colonies appeared on the fifth day. Visible colonies were observed on plates with sucrose concentrations as low as 5mM. These data suggest that, with the sugar secreted by PowerCell expressing cscB and no additional metabolic engineering, it is possible to support another organism.

References

1 Sammy Boussiba, Jane Gibson, Ammonia translocation in cyanobacteria, FEMS Microbiology Letters, Volume 88, Issue 1, July 1991, Pages 1-14, ISSN 0378-1097, 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90692-4

Niederholtmeyer, Henrike, Wolfstadter, Bernd T., Savage, David F., Silver, Pamela A., Way, Jeffrey C. Engineering Cyanobacteria To Synthesize and Export Hydrophilic Products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010 76: 3462-3466

2 Kim, Jihyun F , Lars K Nielsen, Colin T Archer, Sang Yup Lee, Claudia E Vickers, Jin Hwan Park, and Haeyoung Jeong. "The genome sequence of E. coli W (ATCC 9637): comparative genome analysis and an improved genome-scale reconstruction of E. coli ."BioMed Central 12 (2011).

3 Lee, Jeong Wook, Sol Choi, Jin Hwan Park, Claudia E. Vickers, Lars K. Nielsen, and Sang Yup Lee. "Development of Sucrose-utilizing Escherichia Coli K-12 Strain by Cloning β-fructofuranosidases and Its Application for L-threonine Production."Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 88.4 (2010): 905-13. Print.

4 Claudia Argueta, Kamile Yuksek, Michael Summers, Construction and use of GFP reporter vectors for analysis of cell-type-specific gene expression in Nostoc punctiforme, Journal of Microbiological Methods, Volume 59, Issue 2, November 2004, Pages 181-188, ISSN 0167-7012, 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.06.009.

5 M. Sahintoth, S. Frillingos, J.W. Lengeler, H.R. Kaback, Active Transport by the CscB Permease in Escherichia coli K-12, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, Volume 208, Issue 3, 28 March 1995, Pages 1116-1123, ISSN 0006-291X, 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1449.

6 Huang, H. H., D. Camsund, P. Lindblad, and T. Heidorn. "Design and Characterization of Molecular Tools for a Synthetic Biology Approach towards Developing Cyanobacterial Biotechnology." Nucleic Acids Research 38.8 (2010): 2577-593. Print.

7 Lee, SY and Ho Nam Chang. High cell density cultivation of Escherichia coli W using sucrose as a carbon source. Biotechnology Letters 15:9 (1993) 971--974.

8 Lee JS, Lee SY and Sunwon Park. Fed-batch culture of Escherichia coli W by exponential feeding of sucrose as a carbon source. Biotechnology Techniques 11:1 (1997) 59-62.

9 Shukla, VB et al. Production of D(-)-lactate from sucrose and molasses. Biotechnology Letters 26 (2004) 689-693.

"

"