Team:Brown-Stanford/PowerCell/Cyanobacteria

From 2011.igem.org

(→Transformation of Cyanobacteria) |

|||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

== '''Cyanobacteria''' == | == '''Cyanobacteria''' == | ||

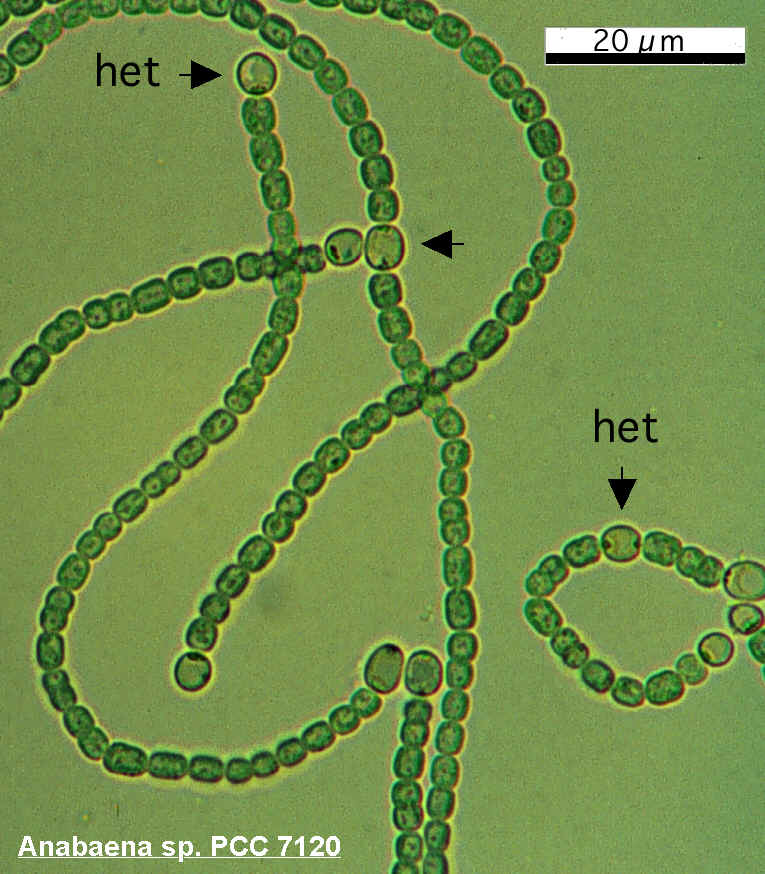

| - | The search for a suitable chassis on which to build the PowerCell project turned up several promising contenders: algae are very efficient solar powerhouses, and E. coli has been engineered to express rubisco and perform a rudimentary form of carbon sequestration, among others. After carefully weighing our options, we hit upon cyanobacteria, commonly (and slightly inaccurately) called blue-green algae. At the end of our deliberations, the grand winner was Anaebaena PCC 7120, a filamentous organism very much resembling a tiny, green, pearl necklace. | + | The search for a suitable chassis on which to build the PowerCell project turned up several promising contenders: algae are very efficient solar powerhouses, and ''E. coli'' has been engineered to express rubisco and perform a rudimentary form of carbon sequestration, among others. After carefully weighing our options, we hit upon cyanobacteria, commonly (and slightly inaccurately) called blue-green algae. At the end of our deliberations, the grand winner was ''Anaebaena'' PCC 7120, a filamentous organism very much resembling a tiny, green, pearl necklace. |

| - | [[File:Brown-Stanford Anabaena mugshot.JPG|300px|thumb|Light micrograph of our Anabaena PCC 7120, 630x brightfield (top) and phase contrast (bottom)]] | + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Anabaena mugshot.JPG|300px|thumb|Light micrograph of our ''Anabaena'' PCC 7120, 630x brightfield (top) and phase contrast (bottom)]] |

| - | The reasons for our choice were severalfold. Our primary requirements were that the organism access nitrogen and carbon dioxide, and accept our DNA in some relatively easy manner. | + | The reasons for our choice were severalfold. Our primary requirements were that the organism be able to access nitrogen and carbon dioxide, and accept our DNA in some relatively easy manner. These will each be explained in greater detail in sections below. In addition, we wanted an organism that could survive on minimal media, produce all of its products in aerobic conditions, and live a happy, fulfilled life with as little auxiliary equipment as possible. |

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

=== '''Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide''' === | === '''Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide''' === | ||

| - | Anaebaena is a diazotroph, or | + | ''Anaebaena'' is a diazotroph, or “N<sub>2</sub> eater.” The organism has evolved a nitrogenase which is capable of overcoming the triple covalent bond between the two nitrogen atoms, although the reaction is oxygen-sensitive and can only take place in an anaerobic environment. |

| - | [[File:Brown-Stanford nitrogenase diagram.png|200px|left|thumb|Nitrogenase | + | [[File:Brown-Stanford nitrogenase diagram.png|200px|left|thumb|Nitrogenase {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/FootnoteNumber|1}}]] |

[[File:Brown-Stanford Heterocysts.JPG|300px|right|thumb|Heterocysts on an Anabaena filament (http://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/103690)]] | [[File:Brown-Stanford Heterocysts.JPG|300px|right|thumb|Heterocysts on an Anabaena filament (http://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/103690)]] | ||

| - | For this | + | For this oxygen sensitivity, many diazotrophic cyanobacteria require anaerobic growth conditions, but ''Anabaena'' has evolved a method of separating oxygen and the N<sub>2</sub> cleaving process: specialized cells, called heterocysts, form along the filament in nitrogen-poor conditions. These specialized cells, visibly larger and darker than the rest, form an anaerobic intracellular microenvironment where the nitrogenase can do its job. The nitrogen-containing products are exported to adjacent vegetative cells via plasmodesmata, through which photosynthesized carbon products return. |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| - | + | ''Anabaena'' can live in aerobic conditions, fix nitrogen and photosynthesize sugars. They are able to produce almost everything they need, making them capable of living on very minimal media—clear water with a few trace minerals. It follows that we can harness their self-sufficiency to provide for more dependent organisms, such as ''E. coli''. All we have to do is enforce some compulsory generosity, and although ''Anabaena'' won’t be as well-fed as it was as a selfish microbe, the ''E. coli'' it is supporting will have a food source where it otherwise would have gone hungry. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | Anabaena can live in aerobic conditions, fix nitrogen and photosynthesize sugars. They are able to | + | |

=== '''Transformation of Cyanobacteria''' === | === '''Transformation of Cyanobacteria''' === | ||

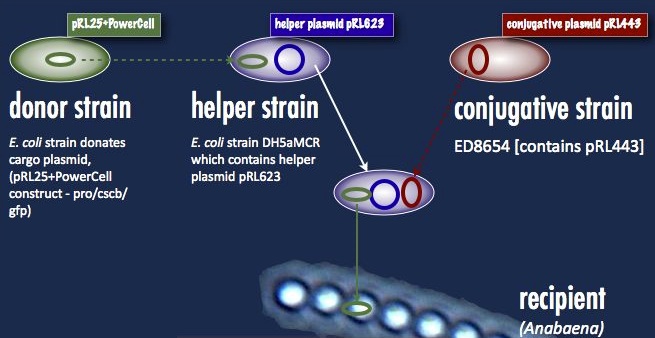

| - | There are cyanobacteria which will accept DNA without complaint. ''Synechocystis elongates'', for example, will simply take up naked DNA in solution and express it. ''Anabaena'' must take its DNA through a rather circuitous path; the DNA construct must first be placed in a cargo plasmid and transformed into E. coli by traditional means. Transfer to Anabaena takes place by conjugation, facilitated by a second E. coli strain carrying a plasmid encoding the machinery for bacterial conjugation. | + | There are cyanobacteria which will accept DNA without complaint. ''Synechocystis elongates'', for example, will simply take up naked DNA in solution and express it. ''Anabaena'' must take its DNA through a rather circuitous path; the DNA construct must first be placed in a cargo plasmid and transformed into ''E. coli'' by traditional means. Transfer to ''Anabaena'' takes place by conjugation, facilitated by a second ''E. coli'' strain carrying a plasmid encoding the machinery for bacterial conjugation. |

| - | Another problem is the propensity of ''Anabaena'' to slice and dice foreign DNA with isoschizomers of the restriction enzymes AvaI, AvaII and AvaIII. This has been addressed with methyltransferases targeting the same sequences; that means a third E. coli strain carrying these methyltransferases (a helper plasmid) participates in the conjugation. At the end of all this, a certain number of cyanobacterial cells take up the DNA, and are selected for with neomycin on minimal media. As soon as the unsuccessful exconjugates and the bacterial parental strains die off, transformant colonies can be picked. One significant hindrance associated with this process is the slow cyanobacterial doubling time; the transformants can take upwards of a week to grow. | + | Another problem is the propensity of ''Anabaena'' to slice and dice foreign DNA with isoschizomers of the restriction enzymes AvaI, AvaII and AvaIII. This has been addressed with methyltransferases targeting the same sequences; that means a third ''E. coli'' strain carrying these methyltransferases (a helper plasmid) participates in the conjugation. At the end of all this, a certain number of cyanobacterial cells take up the DNA, and are selected for with neomycin on minimal media. As soon as the unsuccessful exconjugates and the bacterial parental strains die off, transformant colonies can be picked. One significant hindrance associated with this process is the slow cyanobacterial doubling time; the transformants can take upwards of a week to grow. |

Our first trials were performed with the helper plasmid pDS4101, the conjugative plasmid pRL443 and the cargo plasmid pRL25. pDS4101 does not possess the methyltransferases which can epigenetically protect the incoming DNA from restriction, and so can only be used to transfer plasmids lacking restriction sites, such as pRL25, as a proof of concept. Towards the end of the summer we were able to obtain the helper plasmid pRL623 containing the three methyltransferases which together offer complete protection from restriction inside ''Anabaena''. There was an added obstacle with this new route, however: pRL623 could only be carried against certain ''E. coli'' genetic backgrounds lacking methyl-restricting enzymes, in order to prevent restriction of the host genome. This meant that transfer of the helper plasmid into the cargo plasmid strain before conjugation into ''Anabaena'' would result in the suicide of that cargo strain, and no transformation. The solution to this was transformation by more traditional means of the cargo plasmid into the strain already carrying the helper plasmid; the cargo could then be delivered into ''Anabaena'' without transfer of the dangerous helper plasmid, and the helper plasmid had its opportunity to protectively methylate the cargo prior to transformation. | Our first trials were performed with the helper plasmid pDS4101, the conjugative plasmid pRL443 and the cargo plasmid pRL25. pDS4101 does not possess the methyltransferases which can epigenetically protect the incoming DNA from restriction, and so can only be used to transfer plasmids lacking restriction sites, such as pRL25, as a proof of concept. Towards the end of the summer we were able to obtain the helper plasmid pRL623 containing the three methyltransferases which together offer complete protection from restriction inside ''Anabaena''. There was an added obstacle with this new route, however: pRL623 could only be carried against certain ''E. coli'' genetic backgrounds lacking methyl-restricting enzymes, in order to prevent restriction of the host genome. This meant that transfer of the helper plasmid into the cargo plasmid strain before conjugation into ''Anabaena'' would result in the suicide of that cargo strain, and no transformation. The solution to this was transformation by more traditional means of the cargo plasmid into the strain already carrying the helper plasmid; the cargo could then be delivered into ''Anabaena'' without transfer of the dangerous helper plasmid, and the helper plasmid had its opportunity to protectively methylate the cargo prior to transformation. | ||

| Line 71: | Line 70: | ||

===References=== | ===References=== | ||

| - | + | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Footnote|1|http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Wikitexts/UC_Davis/UCD_Chem_124A:_Berben/Nitrogenase/Nitrogenase_2}} | |

| - | + | ||

{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Foot}} | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Foot}} | ||

Revision as of 15:51, 28 September 2011

CRITERIA: CARBON FIXING, NITROGEN FIXING, MINIMAL MEDIA, ACCEPT DNA (WHY ARE EACH OF THESE IMPORTANT?)

BRIEF EXPLANATION OF PHOTOSYNTHESIS: CHEMICAL EQUATION, PICTURE OF EARTH CARBON CYCLE

DIAZOTROPHY: EXPLAIN WHAT IT IS, SHOW EARTH NITROGEN CYCLE, INTRODUCE PROBLEM OF OXYGEN AND NITROGENASE ACTIVITY -TWO METHODS OF DEALING WITH OXYGEN PROBLEM: UNICELLULAR TEMPORAL CONTROL AND HETEROCYSTS

ON THIS BASIS, WE SELECTED ANABAENA.

ANABAENA IS GROWN ON MINIMAL MEDIA, ACCEPTS DNA (JUST CITE A PAPER AND SAY WE WILL ELABORATE ON THIS PROCESS IN OUR EXPT SECTION)

Cyanobacteria

The search for a suitable chassis on which to build the PowerCell project turned up several promising contenders: algae are very efficient solar powerhouses, and E. coli has been engineered to express rubisco and perform a rudimentary form of carbon sequestration, among others. After carefully weighing our options, we hit upon cyanobacteria, commonly (and slightly inaccurately) called blue-green algae. At the end of our deliberations, the grand winner was Anaebaena PCC 7120, a filamentous organism very much resembling a tiny, green, pearl necklace.

The reasons for our choice were severalfold. Our primary requirements were that the organism be able to access nitrogen and carbon dioxide, and accept our DNA in some relatively easy manner. These will each be explained in greater detail in sections below. In addition, we wanted an organism that could survive on minimal media, produce all of its products in aerobic conditions, and live a happy, fulfilled life with as little auxiliary equipment as possible.

Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide

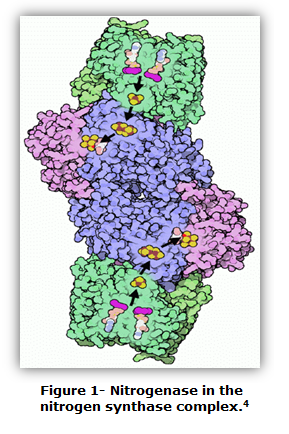

Anaebaena is a diazotroph, or “N2 eater.” The organism has evolved a nitrogenase which is capable of overcoming the triple covalent bond between the two nitrogen atoms, although the reaction is oxygen-sensitive and can only take place in an anaerobic environment.

For this oxygen sensitivity, many diazotrophic cyanobacteria require anaerobic growth conditions, but Anabaena has evolved a method of separating oxygen and the N2 cleaving process: specialized cells, called heterocysts, form along the filament in nitrogen-poor conditions. These specialized cells, visibly larger and darker than the rest, form an anaerobic intracellular microenvironment where the nitrogenase can do its job. The nitrogen-containing products are exported to adjacent vegetative cells via plasmodesmata, through which photosynthesized carbon products return.

Anabaena can live in aerobic conditions, fix nitrogen and photosynthesize sugars. They are able to produce almost everything they need, making them capable of living on very minimal media—clear water with a few trace minerals. It follows that we can harness their self-sufficiency to provide for more dependent organisms, such as E. coli. All we have to do is enforce some compulsory generosity, and although Anabaena won’t be as well-fed as it was as a selfish microbe, the E. coli it is supporting will have a food source where it otherwise would have gone hungry.

Transformation of Cyanobacteria

There are cyanobacteria which will accept DNA without complaint. Synechocystis elongates, for example, will simply take up naked DNA in solution and express it. Anabaena must take its DNA through a rather circuitous path; the DNA construct must first be placed in a cargo plasmid and transformed into E. coli by traditional means. Transfer to Anabaena takes place by conjugation, facilitated by a second E. coli strain carrying a plasmid encoding the machinery for bacterial conjugation.

Another problem is the propensity of Anabaena to slice and dice foreign DNA with isoschizomers of the restriction enzymes AvaI, AvaII and AvaIII. This has been addressed with methyltransferases targeting the same sequences; that means a third E. coli strain carrying these methyltransferases (a helper plasmid) participates in the conjugation. At the end of all this, a certain number of cyanobacterial cells take up the DNA, and are selected for with neomycin on minimal media. As soon as the unsuccessful exconjugates and the bacterial parental strains die off, transformant colonies can be picked. One significant hindrance associated with this process is the slow cyanobacterial doubling time; the transformants can take upwards of a week to grow.

Our first trials were performed with the helper plasmid pDS4101, the conjugative plasmid pRL443 and the cargo plasmid pRL25. pDS4101 does not possess the methyltransferases which can epigenetically protect the incoming DNA from restriction, and so can only be used to transfer plasmids lacking restriction sites, such as pRL25, as a proof of concept. Towards the end of the summer we were able to obtain the helper plasmid pRL623 containing the three methyltransferases which together offer complete protection from restriction inside Anabaena. There was an added obstacle with this new route, however: pRL623 could only be carried against certain E. coli genetic backgrounds lacking methyl-restricting enzymes, in order to prevent restriction of the host genome. This meant that transfer of the helper plasmid into the cargo plasmid strain before conjugation into Anabaena would result in the suicide of that cargo strain, and no transformation. The solution to this was transformation by more traditional means of the cargo plasmid into the strain already carrying the helper plasmid; the cargo could then be delivered into Anabaena without transfer of the dangerous helper plasmid, and the helper plasmid had its opportunity to protectively methylate the cargo prior to transformation.

We are sincerely grateful to Jeff Elhai, Peter Wolk, James Golden and Norman Wang for their crucial help and guidance.

References

1 http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Wikitexts/UC_Davis/UCD_Chem_124A:_Berben/Nitrogenase/Nitrogenase_2

"

"