Team:Brown-Stanford/PowerCell/Cyanobacteria

From 2011.igem.org

Ho.julius.a (Talk | contribs) (→Cyanobacteria) |

(→Anabaena 7120) |

||

| (24 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

{{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Content}} | {{:Team:Brown-Stanford/Templates/Content}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

== '''Cyanobacteria''' == | == '''Cyanobacteria''' == | ||

| - | The search for a suitable chassis on which to build the PowerCell project turned up several promising contenders: algae are very efficient solar powerhouses, and ''E. coli'' has been engineered to express rubisco and perform a rudimentary form of carbon sequestration, among others. After carefully weighing our options, we hit upon cyanobacteria, commonly (and slightly inaccurately) called blue-green algae. | + | The search for a suitable chassis on which to build the PowerCell project turned up several promising contenders: algae are very efficient solar powerhouses, and ''E. coli'' has been engineered to express rubisco and perform a rudimentary form of carbon sequestration, among others. After carefully weighing our options, we hit upon cyanobacteria, commonly (and slightly inaccurately) called blue-green algae. |

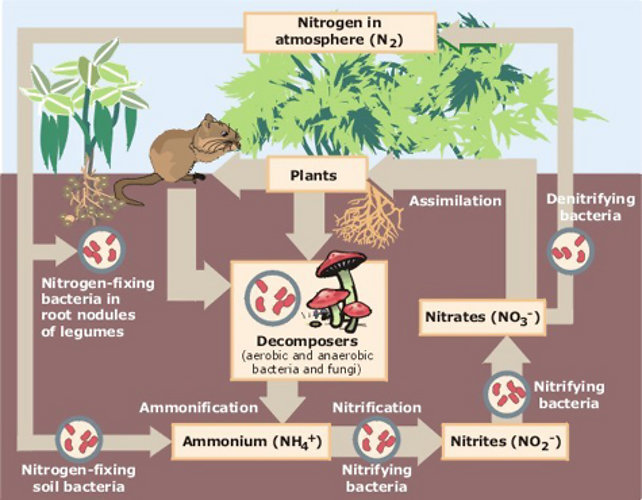

| - | + | <center>[[File:Brown-Stanford cyanobacteria bloom.JPG|300px|none|thumb|Cyanobacteria proliferate in bodies of water and are an important primary producer in the Earth ecosystem]][[File:Brown-Stanford Nitrogen cycle.JPG|300px|none|thumb|Bacteria that fix atmospheric nitrogen are part of the terrestrial nitrogen cycle (photo courtesy the EPA)]]</center> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | [[File:Brown-Stanford cyanobacteria bloom.JPG|300px| | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | [[File:Brown-Stanford Nitrogen cycle.JPG|300px| | + | |

| + | ==='''Anabaena 7120'''=== | ||

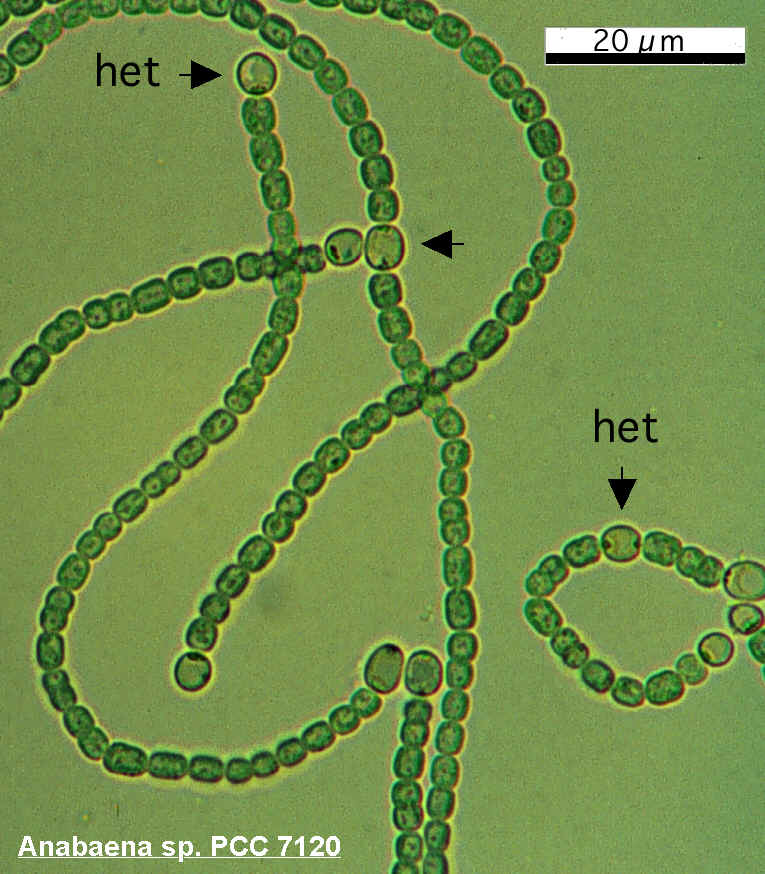

| + | To host PowerCell, we chose a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diazotroph diazotropic] cyanobacterium, ''Anabaena'' 7120. ''Anabaena'' 7120 has several characteristics that make it a good choice of host - most importantly its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into biologically useful forms. | ||

| + | [[File:Brown-Stanford Anabeana.jpg|500px|center|thumb|''Anabaena'' 7120 is a filamentous bacterium capable of both photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation. Light micrograph of one of our Anabaena, 630x bright field]] | ||

| + | ---- | ||

=== '''Nitrogen and Oxygen''' === | === '''Nitrogen and Oxygen''' === | ||

| Line 51: | Line 35: | ||

Heterocysts are specialized cells, visibly larger and darker than the rest, and form thick cell walls which house an anaerobic intracellular microenvironment where the nitrogenase can perform nitrogen fixation. The nitrogen-containing products are exported to adjacent vegetative cells via plasmodesmata, through which photosynthesized carbon products return. Normal (vegetative) cells carry on with photosynthesis. The two cell types then share nutrients up and down the filament, thus providing each cell with all the nutrients it needs. | Heterocysts are specialized cells, visibly larger and darker than the rest, and form thick cell walls which house an anaerobic intracellular microenvironment where the nitrogenase can perform nitrogen fixation. The nitrogen-containing products are exported to adjacent vegetative cells via plasmodesmata, through which photosynthesized carbon products return. Normal (vegetative) cells carry on with photosynthesis. The two cell types then share nutrients up and down the filament, thus providing each cell with all the nutrients it needs. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

''Anabaena'' can live in aerobic conditions, fix nitrogen and photosynthesize sugars. They are able to produce almost everything they need, making them capable of living on very minimal media—clear water with a few trace minerals. It follows that we can harness their self-sufficiency to provide for more dependent organisms, such as ''E. coli''. All we have to do is enforce some compulsory generosity, and although ''Anabaena'' won’t be as well-fed as it was as a selfish microbe, the ''E. coli'' it is supporting will have a food source where it otherwise would have gone hungry. | ''Anabaena'' can live in aerobic conditions, fix nitrogen and photosynthesize sugars. They are able to produce almost everything they need, making them capable of living on very minimal media—clear water with a few trace minerals. It follows that we can harness their self-sufficiency to provide for more dependent organisms, such as ''E. coli''. All we have to do is enforce some compulsory generosity, and although ''Anabaena'' won’t be as well-fed as it was as a selfish microbe, the ''E. coli'' it is supporting will have a food source where it otherwise would have gone hungry. | ||

| - | + | ---- | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

===References=== | ===References=== | ||

Latest revision as of 01:32, 29 October 2011

Cyanobacteria

The search for a suitable chassis on which to build the PowerCell project turned up several promising contenders: algae are very efficient solar powerhouses, and E. coli has been engineered to express rubisco and perform a rudimentary form of carbon sequestration, among others. After carefully weighing our options, we hit upon cyanobacteria, commonly (and slightly inaccurately) called blue-green algae.

Anabaena 7120

To host PowerCell, we chose a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diazotroph diazotropic] cyanobacterium, Anabaena 7120. Anabaena 7120 has several characteristics that make it a good choice of host - most importantly its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into biologically useful forms.

Nitrogen and Oxygen

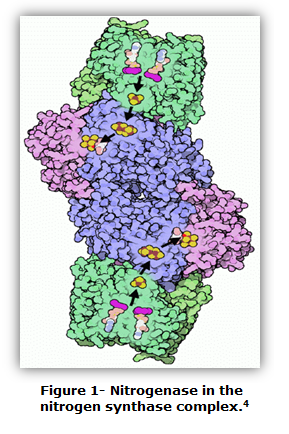

Anaebaena is a diazotroph, or “N2 eater.” The organism has evolved a nitrogenase which is capable of overcoming the triple covalent bond between the two nitrogen atoms, although the reaction is oxygen-sensitive and can only take place in an anaerobic environment.

For this reason, most diazotrophs separate the processes of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation temporally – that is, they photosynthesize in the day and fix nitrogen at night. Anabaena 7120 has a different way around this problem. It forms long filaments of cells containing two different cell types, normal (vegetative) cells, and heterocysts.

Heterocysts are specialized cells, visibly larger and darker than the rest, and form thick cell walls which house an anaerobic intracellular microenvironment where the nitrogenase can perform nitrogen fixation. The nitrogen-containing products are exported to adjacent vegetative cells via plasmodesmata, through which photosynthesized carbon products return. Normal (vegetative) cells carry on with photosynthesis. The two cell types then share nutrients up and down the filament, thus providing each cell with all the nutrients it needs.

Anabaena can live in aerobic conditions, fix nitrogen and photosynthesize sugars. They are able to produce almost everything they need, making them capable of living on very minimal media—clear water with a few trace minerals. It follows that we can harness their self-sufficiency to provide for more dependent organisms, such as E. coli. All we have to do is enforce some compulsory generosity, and although Anabaena won’t be as well-fed as it was as a selfish microbe, the E. coli it is supporting will have a food source where it otherwise would have gone hungry.

References

1 http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Wikitexts/UC_Davis/UCD_Chem_124A:_Berben/Nitrogenase/Nitrogenase_2

"

"