Team:British Columbia/Model2

From 2011.igem.org

| (32 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | |||

<style type="text/css"> | <style type="text/css"> | ||

#slideshow {width:520px; float:left; background-color: white; margin-left: 8px; margin-top:10px;} | #slideshow {width:520px; float:left; background-color: white; margin-left: 8px; margin-top:10px;} | ||

| Line 13: | Line 12: | ||

</br></center></div> | </br></center></div> | ||

<div id="links"> | <div id="links"> | ||

| - | <b> | + | <b>Objective:</b> </br>To predict the impact of the mountain pine beetle (MPB) epidemic on the lodgepole pine tree population in British Columbia (BC), we developed a mathematical model that describes the spread of the MPB population across BC. We applied the model to simulate the spread of the MPB over the next decade (from 2011-2020). Then, we used the model to predict key locations in BC where we may disperse beetles with the synthetic yeast to effectively control the MPB epidemic. Lastly, we propose a formula to estimate the cost required to implement a MPB control strategy. |

</br></br> | </br></br> | ||

<b>Model Creators:</b> Jacob Toth, Joe Ho, Samuel Wu</br></br> | <b>Model Creators:</b> Jacob Toth, Joe Ho, Samuel Wu</br></br> | ||

| - | <b>Model Advisors:</b> Shing Zhan </br></br> | + | <b>Model Advisors:</b> Shing Hei Zhan, Alina Chan </br></br> |

<b>Model Coder:</b> Samuel Wu </br></br> | <b>Model Coder:</b> Samuel Wu </br></br> | ||

<b><a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/9/99/MPB_Epidemic_Model_2.pdf">Download model methodology</b></a></div> | <b><a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/9/99/MPB_Epidemic_Model_2.pdf">Download model methodology</b></a></div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

<div id="bod"> | <div id="bod"> | ||

| - | + | <h3>The Beetle's Strategy</h3></html> | |

[[File:ubcigemmodel2comic2.jpg | center ]] | [[File:ubcigemmodel2comic2.jpg | center ]] | ||

| - | The | + | The MPB live in symbiosis with the bluestain fungus which can break down monoterpenes produced by the tree to deter insect attacks. Their relationship allows the beetle to avoid the toxic effects of the monoterpenes, while the fungus is carried inside the tree where it can grow and colonize. The beetles lay their larvae that consume the fungus for nutrients. Once the larvae grow into adults, they carry the fungus and infect other trees. Meanwhile, the trees turn red and die because the fungus blocks transport of water and nutrients through the tree. Over the last decade, the pine beetle epidemic spread rapidly through North American pine forests, causing mass destruction to forest health and reliant ecosystems. |

| - | <html><h3 | + | <br> |

| + | |||

| + | <html><h3>Our Theoretical Strategy: iSynthase Yeast</h3></html> | ||

To establish high levels of anti-beetle monoterpenes in the trees, we propose the introduction of our monoterpene-producing yeast into the environment. For this, we have two strategies: the iSynthase Trap Box and the Mark-Release-Recapture strategy. Both involve exposing beetles to the synthetic yeast and releasing them to the environment to disperse the yeast along with the pine beetle infestation. | To establish high levels of anti-beetle monoterpenes in the trees, we propose the introduction of our monoterpene-producing yeast into the environment. For this, we have two strategies: the iSynthase Trap Box and the Mark-Release-Recapture strategy. Both involve exposing beetles to the synthetic yeast and releasing them to the environment to disperse the yeast along with the pine beetle infestation. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 33: | ||

[[File:ubcigemmodel2comic.jpg | center ]] | [[File:ubcigemmodel2comic.jpg | center ]] | ||

| - | Previous studies have shown inhibition of bluestain fungus growth upon interaction with certain concentrations of monoterpenes. Assuming that our yeast | + | Previous studies have shown inhibition of bluestain fungus growth upon interaction with certain concentrations of monoterpenes. Assuming that our yeast inhibits the growth of bluestain fungus due to the monoterpenes produced, this will also subdue the mountain pine beetle population that depends on the blue-stain fungus. We predict that the spread of our yeast will be similar to the pine-beetle infestation, with the hope that it will spread from beetle to beetle. Therefore, the spread of our yeast product will fall once pine-beetle population declines. |

[[File:ubcigemmodel2comic22.jpg | center ]] | [[File:ubcigemmodel2comic22.jpg | center ]] | ||

| Line 43: | Line 45: | ||

To evaluate the effectiveness of the synthetic yeast dispersal strategy, one way is to capture beetles in the environment (again either by using a trap box or collecting an infested tree) and determine what percentage carries the synthetic yeast after different periods of time since the start of the program. | To evaluate the effectiveness of the synthetic yeast dispersal strategy, one way is to capture beetles in the environment (again either by using a trap box or collecting an infested tree) and determine what percentage carries the synthetic yeast after different periods of time since the start of the program. | ||

| - | < | + | <br> |

| + | <html><h3>Model Description</h3></html> | ||

A MPB population of size <i>N</i> is described as a collection of <i>n</i> subpopulations. At year <i>t</i>, subpopulation <i>i</i> is centered at <i>c<sup>i</sup><sub>t</sub>=(x<sup>i</sup><sub>t</sub>,y<sup>i</sup><sub>t</sub>)</i> and is normally distributed along the West-East axis (<i>x</i>) with the standard deviation <i>σ<sub>x</sub><sup>i,t</sup></i> and along the North-South axis (<i>y</i>) with <i>σ<sub>y</sub><sup>i,t</sup></i>. The subpopulation expansion rate is defined as the rate of change in the mean subpopulation standard deviation. Two subpopulation expansion rates are defined to reflect two-dimensional expansion: one for the West-East axis (<i>s<sub>x</sub></i>) and the other for the North-South axis (<i>s<sub>y</sub></i>). Suppose that subpopulations expand linearly with time, we can estimate the subpopulation expansion rate along each axis using standard linear regression. The slope is interpreted as the subpopulation expansion rate. Thus, we can conveniently extrapolate the standard deviation of subpopulation <i>i</i> at time <i>t+k</i> along each axis: | A MPB population of size <i>N</i> is described as a collection of <i>n</i> subpopulations. At year <i>t</i>, subpopulation <i>i</i> is centered at <i>c<sup>i</sup><sub>t</sub>=(x<sup>i</sup><sub>t</sub>,y<sup>i</sup><sub>t</sub>)</i> and is normally distributed along the West-East axis (<i>x</i>) with the standard deviation <i>σ<sub>x</sub><sup>i,t</sup></i> and along the North-South axis (<i>y</i>) with <i>σ<sub>y</sub><sup>i,t</sup></i>. The subpopulation expansion rate is defined as the rate of change in the mean subpopulation standard deviation. Two subpopulation expansion rates are defined to reflect two-dimensional expansion: one for the West-East axis (<i>s<sub>x</sub></i>) and the other for the North-South axis (<i>s<sub>y</sub></i>). Suppose that subpopulations expand linearly with time, we can estimate the subpopulation expansion rate along each axis using standard linear regression. The slope is interpreted as the subpopulation expansion rate. Thus, we can conveniently extrapolate the standard deviation of subpopulation <i>i</i> at time <i>t+k</i> along each axis: | ||

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn1.jpg]] | |

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn2.jpg]] | |

The growth of the MPB population is assumed to follow a linear model. Then, the growth rate (<i>v</i>) is simply the slope of the regression equation that predicts MPB population size over time. The above parameters can be estimated from available Geographical Information System (GIS) data that indicate the distribution of MPB across BC. Below, we describe the statistical methods used to estimate those parameters. | The growth of the MPB population is assumed to follow a linear model. Then, the growth rate (<i>v</i>) is simply the slope of the regression equation that predicts MPB population size over time. The above parameters can be estimated from available Geographical Information System (GIS) data that indicate the distribution of MPB across BC. Below, we describe the statistical methods used to estimate those parameters. | ||

| - | < | + | <br> |

| + | |||

| + | <html><h3>Materials and Methods</h3></html> | ||

| + | |||

<b>Converting GIS data to Cartesian coordinates</b><p></p> | <b>Converting GIS data to Cartesian coordinates</b><p></p> | ||

We obtained GIS data showing the distribution of the MPB population in BC between 1999 and 2010 from the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations website (1). We converted the GIS data into raster images at a resolution of 60 dpi (jpeg format) using the commercial ArcGIS software (2). The raster images were converted into Cartesian coordinates using the utilities in the Python Image Library (3). | We obtained GIS data showing the distribution of the MPB population in BC between 1999 and 2010 from the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations website (1). We converted the GIS data into raster images at a resolution of 60 dpi (jpeg format) using the commercial ArcGIS software (2). The raster images were converted into Cartesian coordinates using the utilities in the Python Image Library (3). | ||

<b>Probabilistic clustering and parameter estimation</b><p></p> | <b>Probabilistic clustering and parameter estimation</b><p></p> | ||

| - | Using a model-based clustering approach, we identified clusters of coordinates (interpreted as subpopulations) that fit two-dimensional normal distributions whose standard deviations are allowed to vary. Each data set contains an optimal number of such clusters, which comprise a normal mixture model. To find the optimal number of clusters, we fitted the data set of year 1999 to a range of | + | Using a model-based clustering approach, we identified clusters of coordinates (interpreted as subpopulations) that fit two-dimensional normal distributions whose standard deviations are allowed to vary. Each data set contains an optimal number of such clusters, which comprise a normal mixture model. To find the optimal number of clusters, we fitted the data set of year 1999 to a range of possible cluster numbers (from 1 to 50). The optimal cluster number was selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (4). The number of subpopulations is fixed to 16 in the current model, representing the average of the best 3 optimal models across all years. The mean and covariance matrix of each cluster in the mixture model having the best-fitting cluster number fitted to predict future sizes of beetle populations. Using the parameter values from the optimized mixture model, we estimated the subpopulation expansion rates and the population growth rate using linear regression. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

<b>Model implementation</b><p></p> | <b>Model implementation</b><p></p> | ||

| - | + | Statistical analysis was conducted in the R computing environment (5). The normal mixture modeling and simulations were done using the package mclust (6). The clusters were modeled as ellipsoidal structures that are normally distributed along its major and minor axes (using the “VVI” covariance option in mclust). | |

| + | <b>Simulation</b><p></p> | ||

| + | As the growth of the infected area landed itself to a linear fit, we predicted the infected area for years 2011 to 2020 to simulate the expansion of the MPB population the estimates obtained from the cluster analysis. Taking year 2010 as the initial point, the standard deviation along the West-East axis and that along the North-South axis were extrapolated for each subpopulation using Equation 1 and Equation 2, respectively. The subpopulations inferred in the year 2010 data set are assumed to be stationary. A pattern of MPB population distribution was predicted for each year from 2011 to 2020, and then overlaid onto the pattern observed in year 2010. We assume the pine trees to be distributed across BC based on [http://genetics.forestry.ubc.ca/cfcg/res_in-situ-stats/pinucon.pdf this range map]. We superimposed the predicted MPB population distribution on a 1-to-20,000 scale map of BC (available at http://gis2.forestry.ubc.ca/BCDD.html). | ||

| + | [[File:Numpoints.png | centre ]] | ||

| + | <CENTER><b>Number of infected points (2011 - 2020) from a linear regression to infestation data from (1999 - 2010) </b></CENTER> | ||

| + | <p></p><p></p> | ||

<b>Derivation of the cost formula</b><p></p> | <b>Derivation of the cost formula</b><p></p> | ||

| - | Supposed that, at year <i>t</i>, we design a strategy to control the MPB epidemic by year <i>t</i><sup>'</sup>. The premise of the strategy is to surround each of the constituent subpopulations of the MPB population with a product that hampers MPB expansion. Here, we assume that the product (which is the iSynthase “TrapBox” in the context of the UBC iGEM 2011 project) is completely effective against MPB spread. First, using the current model, we predict the MPB epidemic situation in year <i>t</i><sup>'</sup>. Then, utilizing the theoretical knowledge gained from the prediction, we estimate the cost required to implement the strategy with a cost model proposed below. | + | Supposed that, at year <i>t</i>, we design a strategy to control the MPB epidemic by year <i>t</i><sup>'</sup>. The premise of the strategy is to surround each of the constituent subpopulations of the MPB population with a product that hampers MPB expansion. Here, we assume that the product (which is the iSynthase “TrapBox” in the context of the UBC iGEM 2011 project) is completely effective against MPB spread. First, using the current model, we predict the MPB epidemic situation in year <i>t</i><sup>'</sup>. Then, utilizing the theoretical knowledge gained from the prediction, we estimate the cost required to implement the strategy with a cost model proposed below.<p></p> |

| - | < | + | The cost of the strategy is determined by the duration of product installation and by the amount of the product needed to contain the MPB population. For subpopulation <i>i</i>, the product is installed along the circumference of the ellipsoid structure that encompasses 99.7% of the subpopulation. Thus, the major radius, <i>a<sub>i</sub></i>, and the minor radius, <i>b<sub>i</sub></i>, of the ellipsoid are related to the standard deviations of the distribution: |

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn3.jpg]] | |

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn4.jpg]] | |

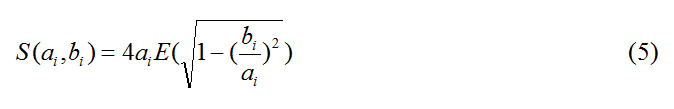

The circumference of the ellipsoid structure (<i>S</i>) is a function of the two radii: | The circumference of the ellipsoid structure (<i>S</i>) is a function of the two radii: | ||

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn5.jpg]] | |

where <i>E(p)</i> is the complete elliptic integral of the second kind: | where <i>E(p)</i> is the complete elliptic integral of the second kind: | ||

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn6.jpg]] | |

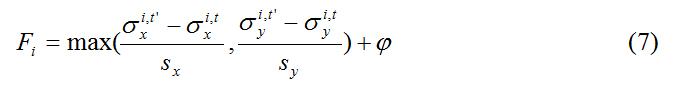

The duration of product installation (<i>F</i>) for subpopulation <i>i</i> is defined as: | The duration of product installation (<i>F</i>) for subpopulation <i>i</i> is defined as: | ||

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn7.jpg]] | |

This estimates the number of years it takes for the subpopulation to reach the product and cease expanding. <i>φ</i> denotes the additional number of years to continually apply the product to ensure that the MPB subpopulation is controlled. Finally, the cost (<i>C</i>) is a function of the duration of product installation and the amount of product used: | This estimates the number of years it takes for the subpopulation to reach the product and cease expanding. <i>φ</i> denotes the additional number of years to continually apply the product to ensure that the MPB subpopulation is controlled. Finally, the cost (<i>C</i>) is a function of the duration of product installation and the amount of product used: | ||

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn8.jpg]] | |

where <i>R</i> is the cost of the product per unit of circumference per year. The cost estimated using this method can be incorporated into the budget for implementing a control strategy. | where <i>R</i> is the cost of the product per unit of circumference per year. The cost estimated using this method can be incorporated into the budget for implementing a control strategy. | ||

| - | < | + | <br> |

| - | + | <html><h3>Predictions</h3></html> | |

| - | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <style type="text/css"> | ||

| + | #slideshow {width:520px; float:left; background-color: white; margin-left: 8px; margin-top:10px;} | ||

| + | #links {width:400px;float:left; background-color: white; margin-left: 8px; margin-top:10px;} | ||

| + | #bod {width:935px; float:left; background-color: white; margin-left: 15px; margin-top:10px;} | ||

| + | </style><center> | ||

| + | <div id="slideshow"><center> | ||

| + | <iframe width="480" height="360" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/SsZUnF6Y6yw" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

| + | </br></center></div> | ||

| + | <div id="links"></div></center> | ||

| + | </br>We simulated the expansion of the MPB population from year 2011 to 2020 using the model framework described above and parameter estimates derived from the probabilistic clustering analysis. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | < | + | <br></br></br></br></br></br></br></br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> |

| - | <b>Emergence of new MPB subpopulations</b> | + | <h3>Model Extensions</h3> |

| + | <b>Emergence of new MPB subpopulations</b><p></p> | ||

The current model assumes that the number of subpopulations remains fixed. In reality, however, new MPB subpopulations can emerge. To model the origin of new subpopulations, we define a subpopulation birth rate. This parameter can be estimated by: | The current model assumes that the number of subpopulations remains fixed. In reality, however, new MPB subpopulations can emerge. To model the origin of new subpopulations, we define a subpopulation birth rate. This parameter can be estimated by: | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| - | + | [[File:UBCiGEM model2 eqn9.jpg]] | |

| - | where | + | <html> |

| + | where <i>T</i> is the total number of years for which MPB distribution data is available (assuming that the years are uniformly spaced). A new subpopulation is assumed to arise from an existing subpopulation. Thus, the initial center of a new subpopulation is expected to be located closely to an existing one. Using this assumption, the initial center of a new subpopulation can be simulated in two steps: 1) randomly select an established subpopulation and 2) then randomly draw a point from a bimodal distribution composed of two evenly massed normal distributions distanced from the center of the parent subpopulation by twice the standard deviation of the parent subpopulation. | ||

| + | <br></br> | ||

| - | <b>Dynamic interactions among MPB and lodgepole pine trees</b> | + | <b>Dynamic interactions among MPB and lodgepole pine trees</b><p></p><p></p> |

The parasite-host relationship between MPB and lodgepole pine trees can be modeled using fundamental ecological principles. First, we can describe the population distribution of the lodgepole pine trees in BC using the current model for MPB. The current model should be able to capture the contraction of lodgepole pine tree subpopulations as a direct consequence of the expansion of MPB subpopulations. Second, we can model the probabilistic interaction between overlapping lodgepole pine tree and MPB subpopulations. The Lotka-Volterra equation can be integrated to model the decline of the lodgepole pine tree population and the rise of the MPB population as a result of the interaction. | The parasite-host relationship between MPB and lodgepole pine trees can be modeled using fundamental ecological principles. First, we can describe the population distribution of the lodgepole pine trees in BC using the current model for MPB. The current model should be able to capture the contraction of lodgepole pine tree subpopulations as a direct consequence of the expansion of MPB subpopulations. Second, we can model the probabilistic interaction between overlapping lodgepole pine tree and MPB subpopulations. The Lotka-Volterra equation can be integrated to model the decline of the lodgepole pine tree population and the rise of the MPB population as a result of the interaction. | ||

| + | <br></br> | ||

| - | <b>Effectiveness of the iSynthase “TrapBox” product</b> | + | <b>Effectiveness of the iSynthase “TrapBox” product</b><p></p> |

| - | While we cannot determine the impact of the iSynthase “TrapBox” product on the MPB population in the wild, we can make explicit assumptions about the effectiveness of the product. We can parameterize the “porousness” of an iSynthase “TrapBox” barrier, modeled by an ellipsoid structure. This directly reflects the effectiveness of the product in preventing the growth of MPB subpopulations surrounded by the product. | + | While we cannot determine the impact of the iSynthase “TrapBox” product on the MPB population in the wild, we can make explicit assumptions about the effectiveness of the product. We can parameterize the “porousness” of an iSynthase “TrapBox” barrier, which is modeled by an ellipsoid structure. This directly reflects the effectiveness of the product in preventing the growth of MPB subpopulations surrounded by the product. |

| - | + | <h3>References</h3><p></p> | |

| - | 1. British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hre/bcmpb/Year7.htm | + | 1. British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hre/bcmpb/Year7.htm<p></p> |

| - | 2. ArcGIS. Version 10. http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis/index.html | + | 2. ArcGIS. Version 10. http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis/index.html<p></p> |

| - | 3. Python Image Library. Version 1.1.7. http://www.pythonware.com/products/pil/ | + | 3. Python Image Library. Version 1.1.7. http://www.pythonware.com/products/pil/<p></p> |

| - | 4. Schwarz G. 1978. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 6:461-4. | + | 4. Schwarz G. 1978. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 6:461-4.<p></p> |

| - | 5. R Development Core Team. 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org | + | 5. R Development Core Team. 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org<p></p> |

| - | 6. Fraley C, Raftery A. MCLUST version 3 for R: normal mixture modeling and model-based clustering. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mclust/index.html | + | 6. Fraley C, Raftery A. MCLUST version 3 for R: normal mixture modeling and model-based clustering. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mclust/index.html<p></p></html> |

Latest revision as of 03:20, 29 October 2011

Modeling the mountain pine beetle epidemic using a probabilistic clustering approach

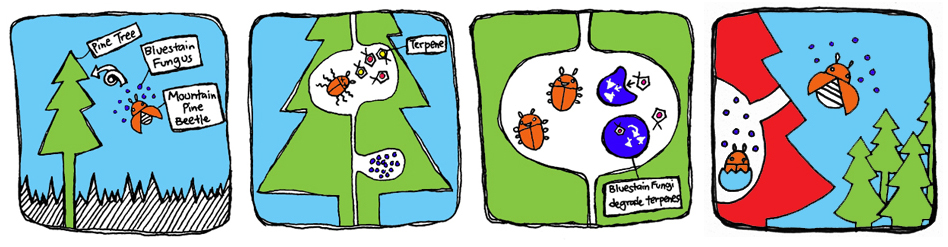

The Beetle's Strategy

The MPB live in symbiosis with the bluestain fungus which can break down monoterpenes produced by the tree to deter insect attacks. Their relationship allows the beetle to avoid the toxic effects of the monoterpenes, while the fungus is carried inside the tree where it can grow and colonize. The beetles lay their larvae that consume the fungus for nutrients. Once the larvae grow into adults, they carry the fungus and infect other trees. Meanwhile, the trees turn red and die because the fungus blocks transport of water and nutrients through the tree. Over the last decade, the pine beetle epidemic spread rapidly through North American pine forests, causing mass destruction to forest health and reliant ecosystems.

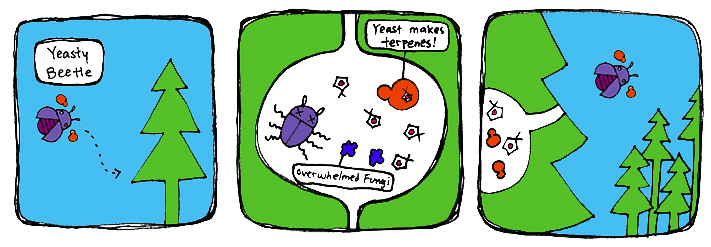

Our Theoretical Strategy: iSynthase Yeast

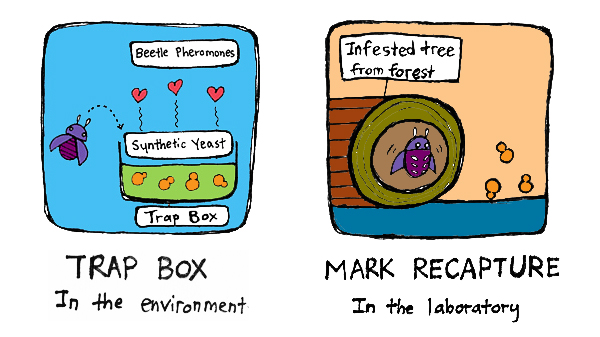

To establish high levels of anti-beetle monoterpenes in the trees, we propose the introduction of our monoterpene-producing yeast into the environment. For this, we have two strategies: the iSynthase Trap Box and the Mark-Release-Recapture strategy. Both involve exposing beetles to the synthetic yeast and releasing them to the environment to disperse the yeast along with the pine beetle infestation.

Previous studies have shown inhibition of bluestain fungus growth upon interaction with certain concentrations of monoterpenes. Assuming that our yeast inhibits the growth of bluestain fungus due to the monoterpenes produced, this will also subdue the mountain pine beetle population that depends on the blue-stain fungus. We predict that the spread of our yeast will be similar to the pine-beetle infestation, with the hope that it will spread from beetle to beetle. Therefore, the spread of our yeast product will fall once pine-beetle population declines.

The iSynthase Trap Box strategy places trap boxes at strategic locations in the forest to attract beetles with pheromones. These beetles enter the box and leave with the synthetic yeast.

The Mark-Release-Recapture strategy involves collecting trees infested with beetles, rearing these in the lab and exposing them to our synthetic yeast, before releasing them back into the environment at strategic locations.

In both cases, the dispersal of beetles back into the environment comes with some risk. Beetles need to use their reserved energy to make several survival decisions including (i) does this forest contain susceptible tree species? (ii) are there other beetles to collaborate with? (iii) does the potential host tree have too much light and warmth? (iv) is this host tree over-populated? (v) what is the defensive capacity of the tree?

To evaluate the effectiveness of the synthetic yeast dispersal strategy, one way is to capture beetles in the environment (again either by using a trap box or collecting an infested tree) and determine what percentage carries the synthetic yeast after different periods of time since the start of the program.

Model Description

A MPB population of size N is described as a collection of n subpopulations. At year t, subpopulation i is centered at cit=(xit,yit) and is normally distributed along the West-East axis (x) with the standard deviation σxi,t and along the North-South axis (y) with σyi,t. The subpopulation expansion rate is defined as the rate of change in the mean subpopulation standard deviation. Two subpopulation expansion rates are defined to reflect two-dimensional expansion: one for the West-East axis (sx) and the other for the North-South axis (sy). Suppose that subpopulations expand linearly with time, we can estimate the subpopulation expansion rate along each axis using standard linear regression. The slope is interpreted as the subpopulation expansion rate. Thus, we can conveniently extrapolate the standard deviation of subpopulation i at time t+k along each axis:

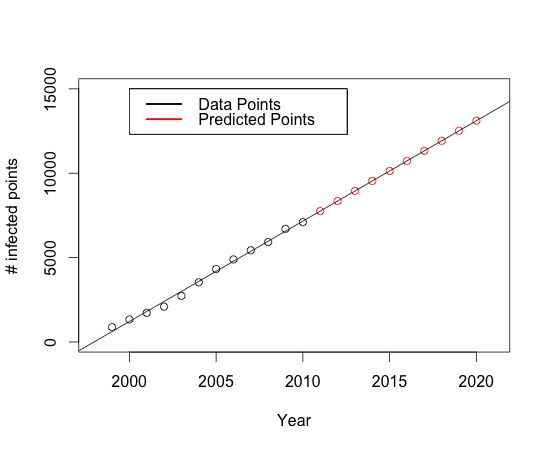

The growth of the MPB population is assumed to follow a linear model. Then, the growth rate (v) is simply the slope of the regression equation that predicts MPB population size over time. The above parameters can be estimated from available Geographical Information System (GIS) data that indicate the distribution of MPB across BC. Below, we describe the statistical methods used to estimate those parameters.

Materials and Methods

Converting GIS data to Cartesian coordinatesWe obtained GIS data showing the distribution of the MPB population in BC between 1999 and 2010 from the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations website (1). We converted the GIS data into raster images at a resolution of 60 dpi (jpeg format) using the commercial ArcGIS software (2). The raster images were converted into Cartesian coordinates using the utilities in the Python Image Library (3).

Probabilistic clustering and parameter estimationUsing a model-based clustering approach, we identified clusters of coordinates (interpreted as subpopulations) that fit two-dimensional normal distributions whose standard deviations are allowed to vary. Each data set contains an optimal number of such clusters, which comprise a normal mixture model. To find the optimal number of clusters, we fitted the data set of year 1999 to a range of possible cluster numbers (from 1 to 50). The optimal cluster number was selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (4). The number of subpopulations is fixed to 16 in the current model, representing the average of the best 3 optimal models across all years. The mean and covariance matrix of each cluster in the mixture model having the best-fitting cluster number fitted to predict future sizes of beetle populations. Using the parameter values from the optimized mixture model, we estimated the subpopulation expansion rates and the population growth rate using linear regression.

Model implementationStatistical analysis was conducted in the R computing environment (5). The normal mixture modeling and simulations were done using the package mclust (6). The clusters were modeled as ellipsoidal structures that are normally distributed along its major and minor axes (using the “VVI” covariance option in mclust).

SimulationAs the growth of the infected area landed itself to a linear fit, we predicted the infected area for years 2011 to 2020 to simulate the expansion of the MPB population the estimates obtained from the cluster analysis. Taking year 2010 as the initial point, the standard deviation along the West-East axis and that along the North-South axis were extrapolated for each subpopulation using Equation 1 and Equation 2, respectively. The subpopulations inferred in the year 2010 data set are assumed to be stationary. A pattern of MPB population distribution was predicted for each year from 2011 to 2020, and then overlaid onto the pattern observed in year 2010. We assume the pine trees to be distributed across BC based on [http://genetics.forestry.ubc.ca/cfcg/res_in-situ-stats/pinucon.pdf this range map]. We superimposed the predicted MPB population distribution on a 1-to-20,000 scale map of BC (available at http://gis2.forestry.ubc.ca/BCDD.html).

The cost of the strategy is determined by the duration of product installation and by the amount of the product needed to contain the MPB population. For subpopulation i, the product is installed along the circumference of the ellipsoid structure that encompasses 99.7% of the subpopulation. Thus, the major radius, ai, and the minor radius, bi, of the ellipsoid are related to the standard deviations of the distribution:

The circumference of the ellipsoid structure (S) is a function of the two radii:

where E(p) is the complete elliptic integral of the second kind:

The duration of product installation (F) for subpopulation i is defined as:

This estimates the number of years it takes for the subpopulation to reach the product and cease expanding. φ denotes the additional number of years to continually apply the product to ensure that the MPB subpopulation is controlled. Finally, the cost (C) is a function of the duration of product installation and the amount of product used:

where R is the cost of the product per unit of circumference per year. The cost estimated using this method can be incorporated into the budget for implementing a control strategy.

Predictions

Model Extensions

Emergence of new MPB subpopulations The current model assumes that the number of subpopulations remains fixed. In reality, however, new MPB subpopulations can emerge. To model the origin of new subpopulations, we define a subpopulation birth rate. This parameter can be estimated by:

where T is the total number of years for which MPB distribution data is available (assuming that the years are uniformly spaced). A new subpopulation is assumed to arise from an existing subpopulation. Thus, the initial center of a new subpopulation is expected to be located closely to an existing one. Using this assumption, the initial center of a new subpopulation can be simulated in two steps: 1) randomly select an established subpopulation and 2) then randomly draw a point from a bimodal distribution composed of two evenly massed normal distributions distanced from the center of the parent subpopulation by twice the standard deviation of the parent subpopulation.

Dynamic interactions among MPB and lodgepole pine trees

Effectiveness of the iSynthase “TrapBox” product While we cannot determine the impact of the iSynthase “TrapBox” product on the MPB population in the wild, we can make explicit assumptions about the effectiveness of the product. We can parameterize the “porousness” of an iSynthase “TrapBox” barrier, which is modeled by an ellipsoid structure. This directly reflects the effectiveness of the product in preventing the growth of MPB subpopulations surrounded by the product.

"

"