Team:British Columbia/Background

From 2011.igem.org

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

'''In nature, monoterpenes are synthesized and secreted by trees as a defense against invading beetles and fungi. The bluestain fungus and mountain pine beetle are in a symbiotic relationship where the fungus deactivates toxic terpenoids and enables the survival of the beetle, which in turn facilitates the spread of the fungus from tree to tree. Meanwhile, from an industrial point of view, various monoterpenes are involved in the production of pharmaceuticals, flavours/fragrances and biofuels. The 2011 UBC iGEM team aims to address both environmental and industrial aspects by engineering yeast that produce monoterpenes with high yield at low cost. We will optimize yeast metabolism for monoterpene production and potentially use this yeast to inspire solutions to the pine beetle epidemic.''' | '''In nature, monoterpenes are synthesized and secreted by trees as a defense against invading beetles and fungi. The bluestain fungus and mountain pine beetle are in a symbiotic relationship where the fungus deactivates toxic terpenoids and enables the survival of the beetle, which in turn facilitates the spread of the fungus from tree to tree. Meanwhile, from an industrial point of view, various monoterpenes are involved in the production of pharmaceuticals, flavours/fragrances and biofuels. The 2011 UBC iGEM team aims to address both environmental and industrial aspects by engineering yeast that produce monoterpenes with high yield at low cost. We will optimize yeast metabolism for monoterpene production and potentially use this yeast to inspire solutions to the pine beetle epidemic.''' | ||

| + | |||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Revision as of 16:56, 12 August 2011

Abstract

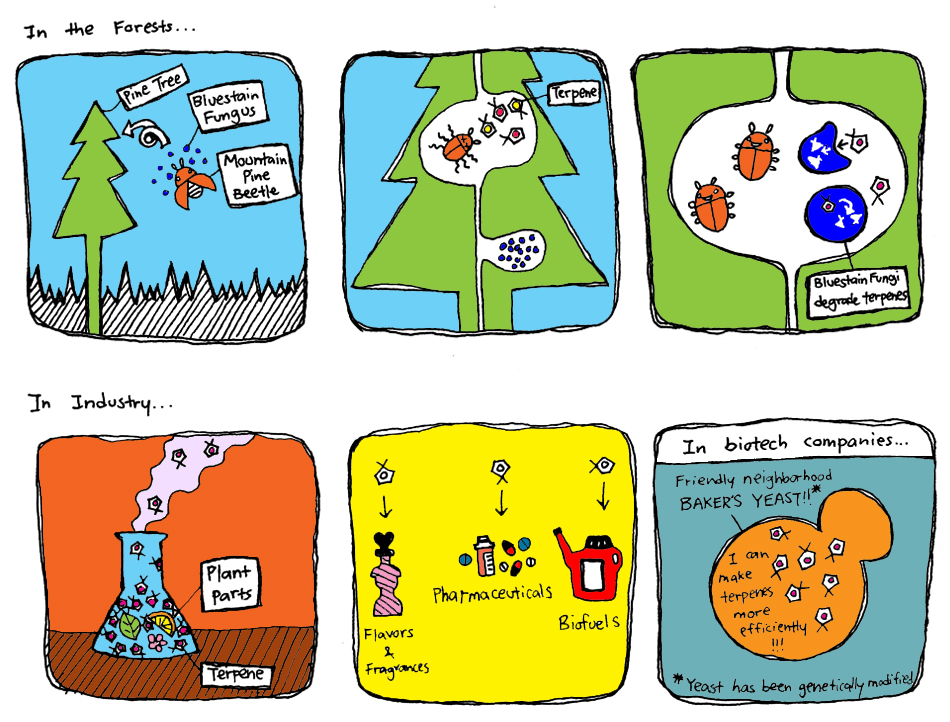

In nature, monoterpenes are synthesized and secreted by trees as a defense against invading beetles and fungi. The bluestain fungus and mountain pine beetle are in a symbiotic relationship where the fungus deactivates toxic terpenoids and enables the survival of the beetle, which in turn facilitates the spread of the fungus from tree to tree. Meanwhile, from an industrial point of view, various monoterpenes are involved in the production of pharmaceuticals, flavours/fragrances and biofuels. The 2011 UBC iGEM team aims to address both environmental and industrial aspects by engineering yeast that produce monoterpenes with high yield at low cost. We will optimize yeast metabolism for monoterpene production and potentially use this yeast to inspire solutions to the pine beetle epidemic.

Background

From left to right: a view from Mount Fraser of dying pine trees turning red, a pine beetle, the effects of the bluestain fungus on a pine tree.

The mountain pine beetle (MPB) outbreak in British Columbia, Canada is the largest and most widespread of its kind in North America. This epidemic has killed millions of acres of lodgepole pine trees, endangering the forest health, which hosts a wide range of ecosystems, and threatening the economic, social, and cultural stability of our beautiful province. By 2013, according to the BC Ministry of Forests and Range, mortality of all merchantable pine trees is projected to be as high as 80%.

The blue stain fungus (Grosmannia clavigera) that lives in symbiosis with the MPB also plays a key role in the infestation. By laying their eggs, the beetles simultaneously introduce the blue stain fungus into the sapwood, which helps prevent the tree’s natural defences, a resin flow, from repelling and killing beetles. Thus, both the beetle and fungus are able to overcome the tree’s defences and colonize the insides of the tree. The fungus cuts off water and nutrient transport within the tree while beetle larvae feed off the tree. Within a year, the pine tree will die from lack of water and nutrient transport and its needles will turn red. Mature MPB will leave the dying tree and move on to the next host tree. In the years following the attack, the tree will turn gray with very little foliage. Most of this wood is unsalvageable due to the bluish-black stain left behind on the wood by the fungi. With vast amount of pines being killed, this has also become a fire hazard for BC. The MPB have always been present in nature and have never been a problem until the beginning of this century. Recent climate changes has resulted in warmer winters which has permitted the prolonged survival of these beetles during the winter. Therefore, its population has grown substantially over the past 15 years. The government of Canada and BC’s Ministry of Forestry have already committed over $956 million dollars to mitigate the spread of the MPB to more pine trees in BC. However, no permanent solution has been found so far.

A tremendous amount of research has been invested in studying the genetics and molecular systems of the three players involved: the pine tree, the MPB, and the blue stain fungus. Interestingly, it was noted that not all pine trees in the outbreak area are infested with the MPB. This begs the question: why do some trees not get attacked by the MPB? Researchers have explored this question through genomic studies comparing attacked pines to those left unharmed. A greater expression of genes related to monoterpene production was observed in unharmed trees. In nature, these monoterpenes, a class within the family of terpeniods, are synthesized and secreted by trees as a defence mechanism against insect and fungi infestation within the tree. Despite this finding, the bluestain fungus has also adapted to the tree’s natural defenses by degrading these terpenoids and removing it from its system, allowing the fungi and the MPB to survive under these toxic conditions. However, researchers have postulated that the blue stain fungus is able to evade these conditions only by attacking stressed trees, where levels of monoterpenes produced are less than normal and thus more susceptible to attacks.

"

"