Team:Harvard/Project

From 2011.igem.org

Overview | Design | Synthesize | Test | Zinc Finger Background | Protocols

Massively Multiplexed Zinc Finger Protein Engineering

Zinc finger proteins are specialized proteins that bind to DNA. Due to their ability to target highly specific DNA sequences, zinc finger proteins offer great potential for gene therapy and personalized medicine: recently, they were shown to be effective in conferring HIV resistance and treating hemophilia in mice. In the past, however, designing new zinc finger proteins - a necessity for individualized gene therapy - has been prohibitively expensive and time consuming. For more information about zinc fingers, see here. Our goal is to create zinc finger proteins that bind to DNA triplets that haven't been bound before: triplets for which no zinc finger protein currently exists.

For our project, team members created and tested thousands of zinc fingers at a cost feasible for most labs. To do so, we harnessed three novel synthetic biology technologies: chip-based synthesis[1], which allows for thousands (even millions) of DNA strands to be synthesized concurrently; multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE)[2][3]; and lambda red recombineering [4][5], both of which make direct edits of the bacterial genome possible and can replace the used of small, cumbersome plasmids.

See our results page: using these methods, we found up to 15 novel zinc fingers, which are still being characterized.

See here for our official abstract, and our acknowledgments page.

To achieve this result, our project had three main steps:

1. Design

Use a bioinformatics approach to predict 55,000 zinc finger sequences.

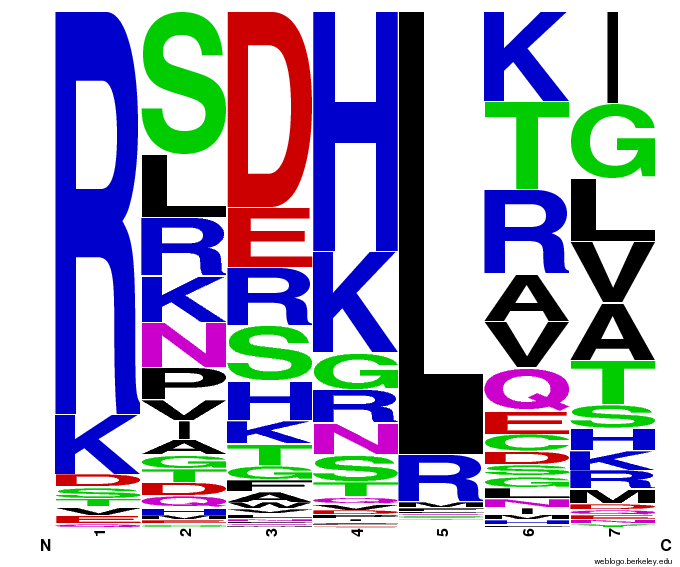

As the structure and binding interactions of zinc fingers are not yet understood, our project utilized bioinformatics and computational analysis of the limited existing data to make “educated guesses” of what amino acid sequences will bind to our desired target sequence.

Team members chose 6 target sequences in the human genome (finding these sequences using a binding site finder tool written by a team member) that no currently-existing zinc finger is able to bind to. The sequences were selected from genes that cause colorblindness, some types of cancer, and high cholesterol. These targets were chosen after conducting an extensive literature search, with the most useful information coming from a previous zinc finger study called CODA[6].

Team members emailed the OPEN consortium[7] and Dr. Anton Persikov[8] to acquire their respective databases of zinc fingers: Persikov had compiled the results of the past 20 years of zinc finger research (everything before OPEN), and OPEN had found many more since then. In all, around 1,700 unique DNA triplet/zinc finger helix pairs were discovered. Team members then decided how to analyze this data for the best chance of binding our target sequences, and programmed their ideas into a [http://sourceforge.net/projects/harvardigem/ Python program] to generate 55,000 potential zinc fingers (55,000 is the number of sequences that can be built using chip-based DNA synthesis).

For a complete overview of how our zinc fingers were designed, see Design.

2. Synthesize

Use chip-based DNA synthesis to make these 55,000 sequences simultaneously, then insert the oligos into E.coli.

Once our team generated these 55,000 sequences, we needed a way to bring them from a computer's memory into the real world. Using chip synthesis of DNA (generously contributed by Agilent Technologies, a sponsor of iGEM, in partnership with our mentors in the Church Lab), all of these sequences were built simultaneously, then sent to us in a single 50µL tube.

For more information about how the chip was created, see the original 2010 paper by Kosuri et al[1]. Cost of chip synthesis is around $.00091 per DNA base, compared to ~$0.40–1.00 per base with current commercial pricing[1]. Thus, chip synthesized DNA has the potential to be up to a factor of 1,000 times cheaper than current mainstream methods of DNA synthesis.

Chip synthesis results in a pool of single-stranded oligos, designed with primer tags, which allow for the amplification of specific sub-pools: in our team's case, we used 6 sub-pools, one for each of our target sequences.

For a complete overview of how our zinc finger DNA went from chip to being expressed in E.coli, see Synthesize.

3. Test

Use a genomic metabolic selection system to test which zinc finger sequences successfully bind DNA.

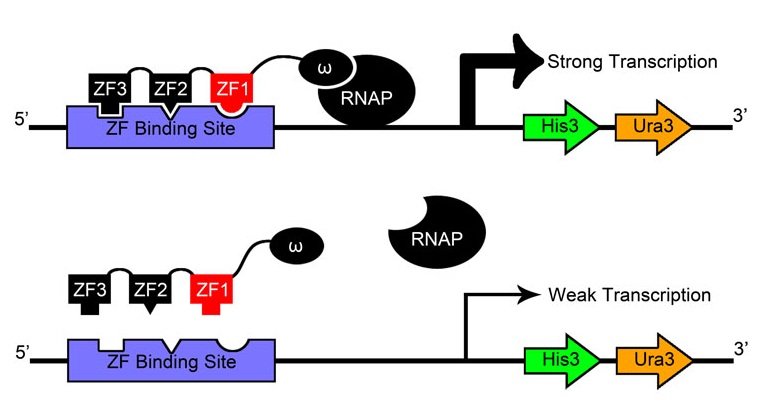

After creating and expressing 55,000 novel zinc finger sequences, our team needed to determine which ones effectively bind to their respective target sites. By tying zinc finger binding to cell survival (using an efficient selection system) all cells without successful binders would die, and thus living colonies indicate a viable zinc finger.

Team members constructed a one-hybrid selection system based off a metabolic system designed by Meng et al[9] which tied zinc finger binding to histidine production. When grown in media without histidine, the cells can only survive if a zinc finger-omega subunit of RNA polymerase (also knocked out in the strain) fusion protein binds successfully and initiates creation of histidine.

Where our team's selection departs from the one described by Meng and others is its use of a genome-based rather than plasmid-based system. Not only did team members knock out HisB, PyrF, and rpoZ ourselves using the newly developed techniques of MAGE and lambda red, we also inserted the zinc finger binding site construct directly into the genome instead of expressing it in the cell on a vector.

For a complete overview of how our selection system was designed, tested, and optimized, see Test.

Results

See our results page for a summary of our most significant findings.

By submitting the necessary strains and parts to the registry, and publishing these easy-to-follow protocols along with our source code, it is our hope that future iGEM teams will also use these techniques in their own synthetic biology projects.

Technological Applications

Our zinc fingers and their clinical applications are a new technology that maximize efficiency and decrease cost. The novel methods we employed in our project have the potential to revolutionize synthetic biology practices, and the way that future iGEM competitions are conducted. To learn more about the technological applications of our project, please see our Technology page.

References

1. Sriram Kosuri, Nikolai Eroshenko, Emily M LeProust, Michael Super, Jeffrey Way, Jin Billy Li, George M Church. (2010). Scalable gene synthesis by selective amplification of DNA pools from high-fidelity microchips. Nature Biotechnology, 28(12):1295-9. [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v28/n12/full/nbt.1716.html]

2. Harris H. Wang, Farren J. Isaacs, Peter A. Carr, Zachary Z. Sun, George Xu, Craig R. Forest, George M. Church. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. (2009). Nature, 460(7257):894-8. [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v460/n7257/full/nature08187.html]

3. Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Wang HH, Lajoie MJ, Sterling B, Kraal L, Tolonen AC, Gianoulis TA, Goodman DB, Reppas NB, Emig CJ, Bang D, Hwang SJ, Jewett MC, Jacobson JM, Church GM. (2011). Precise manipulation of chromosomes in vivo enables genome-wide codon replacement. Science, 333(6040):348-53. [http://www.sciencemag.org/content/333/6040/348.full]

4. Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, et al. (2000). An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97(11): 5978-5983.[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC165854/]

5. Mosberg JA, Lajoie MJ, Church GM. Lambda red recombineering in Escherichia coli occurs through a fully single-stranded intermediate. Genetics 2010;186:791-799.[http://www.genetics.org/content/186/3/791]

6. Jeffry D Sander, Elizabeth J Dahlborg, Mathew J Goodwin, Lindsay Cade, Feng Zhang, Daniel Cifuentes, Shaun J Curtin, Jessica S Blackburn, Stacey Thibodeau-Beganny, Yiping Qi, Christopher J Pierick, Ellen Hoffman, Morgan L Maeder, Cyd Khayter, Deepak Reyon, Drena Dobbs, David M Langenau, Robert M Stupar, Antonio J Giraldez, Daniel F Voytas, Randall T Peterson,Jing-Ruey J Yeh, J Keith Joung. Selection-free zinc-finger-nuclease engineering by context-dependent assembly (CoDA)(2011). Nature Methods 8, 67–69. [http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v8/n1/full/nmeth.1542.html]

7. Morgan L. Maeder, Stacey Thibodeau-Beganny, Anna Osiak, David A. Wright, Reshma M. Anthony, Magdalena Eichtinger, Tao Jiang, Jonathan E. Foley, Ronnie J. Winfrey, Jeffrey A. Townsend, Erica Unger-Wallace, Jeffry D. Sander, Felix Müller-Lerch, Fengli Fu, Joseph Pearlberg, Carl Göbel, Justin P. Dassie, Shondra M. Pruett-Miller, Matthew H. Porteus, Dennis C. Sgroi, A. John Iafrate, Drena Dobbs, Paul B. McCray Jr., Toni Cathomen, Daniel F. Voytas, J. Keith Joung. Rapid “Open-Source” Engineering of Customized Zinc-Finger Nucleases for Highly Efficient Gene Modification (2008). Molecular Cell Volume 31, Issue 2, 25 July 2008, Pages 294-301.[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1097276508004619]

8. Anton Persikov, PhD. [http://www.princeton.edu/~persikov/publications.html]

9. Xiangdong Meng, Michael H Brodsky, Scot A Wolfe. A bacterial one-hybrid system for determining the DNA-binding specificity of transcription factors. (2005). Nature Biotechnology, 23(8): 988-994. [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v23/n8/pdf/nbt1120.pdf]

"

"