Team:Harvard/Project/Test

From 2011.igem.org

Overview | Design | Synthesize | Test | Zinc Finger Background | Protocols

Contents |

Background and Overview

After creating 55,000 novel zinc finger sequences, we need to determine which ones effectively bind to their respective target sites. One possible method is to screen for hits, relying on a marker like fluorescence to pick out colonies with zinc finger binding. Though effective, screening requires searching for hits among a large amount of background; accordingly, we chose to use a more efficient system of selection to identify working zinc finger arrays. By tying zinc finger binding to cell survival, all cells without successful binders would die, and thus every colony present would likely represent a viable hit.

We constructed two different one-hybrid selection systems. The first was based off the metabolic system designed by Meng et al (2005) which tied zinc finger binding to histidine production. Under the control of a zinc finger binding site (ZFB) are the genes His3 and URA3, the yeast analogs of the E. coli genes HisB and PyrF (both of which were knocked out in the selection strain). When grown in media without histidine, the cells can only survive if a zinc finger-omega subunit of RNA polymerase (also knocked out in the strain) fusion protein binds successfully to the ZFB and initiates expression of His3. Strong binders can be distinguished from weak ones by addding 3-AT, a competitive inhibitor of His3. Furthermore, to test for inherently leaky promoters, the strain can be grown without zinc fingers in a media containing 5-FOA, which is broken down by URA3 into a toxin. If the ZFB promoter is constitutively on, the cells will express URA3, break down 5-FOA, and die.

The second selection system used TolC, a membrane pump that can remove toxins like [http://msds.chem.ox.ac.uk/SO/sodium_dodecyl_sulfate.html Sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)] from the cell. TolC expression was placed under the control of a zinc finger binding site and the cells were grown in media containing SDS. If the zinc finger array successfully bound to the ZFB, TolC would be produced and SDS would be pumped out of the cell, allowing it to survive. Although we did successfully construct this system, we found that it was less sensitive than the His3 metabolic selection: while the His3 system could recognize hits diluted one in one million of background, TolC could only identify one in one hundred (see One-Hybrid Selection results for details). We accordingly only used the His3-URA3 system to test our zinc finger libraries.

Genome Editing

Where our selection departs from the one described by Meng and others is its use of a genome-based rather than plasmid-based system. Not only did we knock out HisB, PyrF, and rpoZ ourselves using the newly developed techniques of multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) and lambda red, we also inserted the zinc finger binding site-His3-URA3 construct directly into the genome instead of expressing it in the cell on a vector (see MAGE and Lambda red results for details). We then used lambda red to directly edit the zinc finger binding site on the genome. While plasmids are easily lost during cell division, the genome is a very stable location, and each cell will have exactly one copy of the selection system, preventing artifacts in the data from one cell by chance having more His3 genes than another. With this selection strain we present the genome as the next stage of Biobrick development: standardized parts, we have shown, can now be inserted directly into the bacterial genome instead of being assembled on multiple plasmids.

Wolfe Selection System

The Wolfe selection system (Figure 1) utilizes a metabolic selection scheme. In this selection strain, the endogenous HisB, pyrF, and rpoZ genes have been knocked out via lambda-red and MAGE. This eliminates the cell’s ability to synthesize histidine, pyrF, and the omega-subunit of RNA polymerase, respectively. In the place of HisB and pyrF, the homologous genes His3 and Ura3 have been placed on the genome, with transcription regulated by zinc finger arrays binding upstream. The cells undergo selection in minimal media. Thus, without a zinc finger binding event, the cell is unable to synthesize histidine and dies. To select against a leaky promoter that transcribes the genes in the absence of zinc finger binding, 5-FOA can be added to the selection media. If the promoter is leaky, URA3 will be expressed, and the cell will convert 5-FOA to the toxic product 5-fluorouracil, causing cell death. An alternate method of selecting against false positives is to add 3-AT to the selection media. 3-AT is a selective inhibitor of histidine synthase. Addition of 3-AT would thus select against weak zinc finger binders, leaving only the strongest binders with the ability to activate transcription to the level that permits cell survival.

TolC Selection System

Although not a metabolic selection system, the TolC system works similarly, linking gene transcription to cell survival. TolC is a gene encoding for a membrane pump protein that can export toxins such as [http://msds.chem.ox.ac.uk/SO/sodium_dodecyl_sulfate.html Sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)] out of the cell. Selection is accomplished by linking TolC expression to upstream zinc finger binding events while simultaneously introducing SDS into the selection media. Non-specific zinc fingers are unable to active TolC expression, and the cells are thus unable to export SDS out of the cell, leading to cell death. Meanwhile, zinc finger binders successfully activate TolC expression, allowing cells to survive in spite of SDS being present in selection media. Negative selection against leaky promoters is accomplished in the TolC system through addition of colicins to the selection media. Colicins are toxins that require the TolC transporter in order to access the cell. As a result, if the promoter activates TolC transcription in the absence of zinc finger binding, colicins will be allowed to enter the cell, leading to cell death. Fine-tuning of the TolC selection system is accomplished by adding varying amounts of SDS to the selection media, with higher concentrations of SDS only allowing the strongest zinc finger binders to survive.

Building the selection strain: MAGE

For a detailed explanation of how MAGE works, check out our MAGE technology page. For a step-by-step procedure, see Protocols.

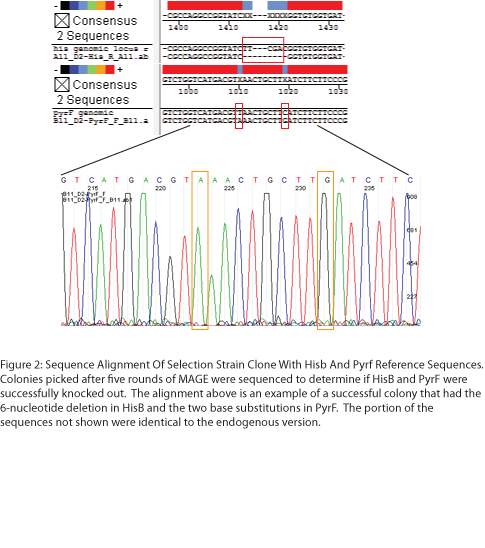

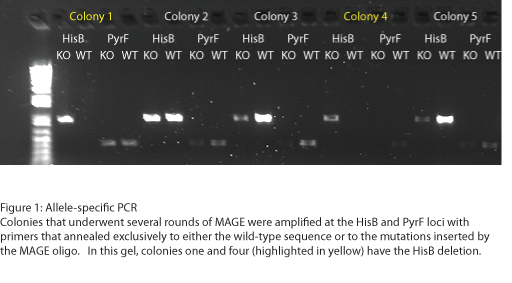

To test the zinc fingers constructed by chip synthesis, we used a one-hybrid system tying zinc finger binding to cell survival (Meng et al, 2005). Under the control of a zinc finger binding site were two yeast genes: His3, a positive metabolic selector, and URA3, a negative selector to eliminate leaky promoters. To create a selection strain for this system, we accordingly knocked out the endogenous E. coli homologs (HisB and PyrF, respectively) using multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE). The PyrF MAGE oligo inserted two early in-frame stop codons by substituting 8T-->A and 16C-->G, while the HisB oligo deleted 6 in-frame nucleotides (694-699) coding for VE. 5 rounds of MAGE were performed in an EcNR2 E. coli line using both oligos simultaneously (see Protocols for exact procedure) and the resulting colonies underwent allele-specific PCR (Figure 1) and were sequenced at the HisB and PyrF loci (Figure 2). We chose a colony that contained both the HisB deletion and the PyrF substitutions as the basis of our selection strain.

Building the selection strain: Lambda Red Recombineering

For a detailed explanation of how Lambda Red recombineering works, check out our Lambda Red technology page. For a step-by-step procedure, see Protocols.

Kan-ZFB-wp-His3-URA3

In this case, for the his3 ura3 system, we inserted, in order, a Kanamycin cassette (in reverse orientation, so that it does not transcribe through the rest of the insert), the zif268 binding site (ZFB), a weak promoter, His3, and URA3. The weak promoter has low levels of transcription on its own, but high levels of transcription when bound to the ω-subunit that is attached to the ZFP (Zinc Finger Protein). After recombineering, the bacteria were plated on kanamycin agar plates to select for the insert.

Tet-ZFB-wp

After we got the selection system working with the zif268 protein and binding site, we swapped out the ZFB for the other sequences, and switched out the Kanamycin cassette for a Tetracycline cassette (also in reverse orientation). This allowed us to change the binding site and select for cells that had the changed binding site.

Zeocin substituting rpoZ

915px In this case, the rpoZ gene is the bacterial homolog of the ω-subunit on the expression plasmid for the ZFP (Zinc Finger Protein). In order to bind the level of transcription of His3-URA3 to the expression of the ZFP, it would need to be knocked out, so that there would be a reduced level of constitutive expression of the his3-ura3. Since rpoZ is a RNA polymerase subunit, knocking it out would reduce the viability of the bacteria, so we could not simply knock it out using MAGE. As a result, we used a zeocin cassette to confer an antibiotic resistance to the bacteria, which we then selected for through zeocin agar plates. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC209740/pdf/jbacter00169-0047.pdf D. R. Gentry and R. R. Burgess, Gene 48:33-40, 1986]

Fig.1) Gel image illustrating that zeocin has been inserted in place of rpoZ. Colonies 1 through 4 were picked off from a zeocin plate, and were thereby selected for zeocin expression. Lanes 1, 3, 5, 7 show the 650bp band that resulted from doing PCR with rpoZ_R (a primer flanking the rpoZ site) and zeocin_R (a primer internal to the zeocin cassette). Lane 9 has no band, as the control has the endogenous rpoZ and not zeocin at that locus, and zeocin_R can not bind anywhere. Lanes 2,4,6 show the larger band when using rpoZ_F and rpoZ_R (the two primers flanking the rpoZ region) to PCR out the zeocin cassette, compared to lane 10, where the same primers are used to PCR out the smaller rpoZ gene. Lane 8 shows no band as the PCR had not worked properly, but lane 7 shows that the zeocin cassette has been inserted into the bacteria from this colony.

Figure 2. Gel image illustrating that the Kan-ZFB-wp construct has been inserted into the genome. Lanes 1,2,3,4 show the larger band as the Kan-ZFB-wp construct is about 1400bp in length. Lane 5, the control, shows a much smaller band as the endogenous promoter is only about 400bp long.

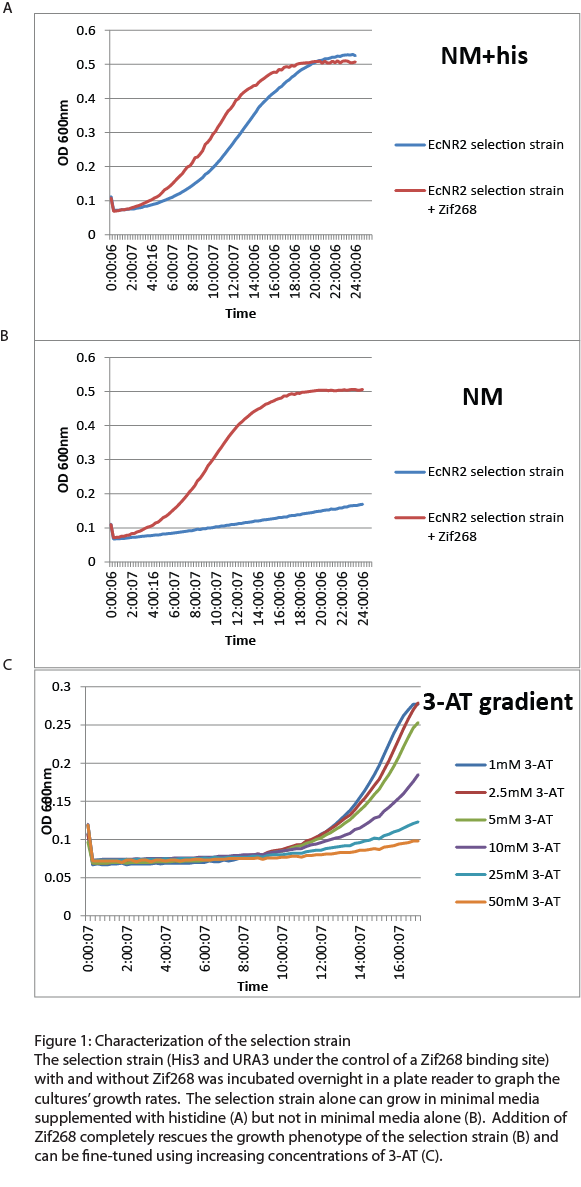

Fine-tuning the one-hybrid selection system

After the one-hybrid His3-URA3 strain was constructed using lambda red and MAGE, we characterized its growth phenotype in preparation for the chip-synthesized zinc fingers. Cultures with the Zif268 binding site either with and without the Zif268 protein were grown overnight in a plate reader to chart their growth under various conditions by measuring the absorbance levels at 600nm. As expected, the strain without Zif268 grew normally in complete media but failed to grow in NM media without histidine (Figure 1A). Zif268 successfully resuced the growth phenotype in NM (Figure 1B) and reached similar saturation levels to cultures grown in NM+histidine. Addition of 5-FOA killed the Zif268 cultures because of their expression of URA3 but did not have a great effect on the selection strain alone, showing that the zinc finger binding site promoter is not inherently leaky. 3-AT, the competitive inhibitor of His3, also fine-tuned selection: Zif268 cultures grew less as 3-AT concentration increased. Overall, the strain showed the proper phenotypes and successfully illustrated selection for zinc finger binding.

For the zinc fingers synthesized from the chip, the selection strain would need to be able to recognize low numbers of hits among a high level of background. Approximately 9000 different zinc fingers were designed for each binding site, and all 9000 are unlikely to successfully bind to the target, so we tested the sensitivity of the selection strain by diluting Zif268 into zinc finger plasmids that would not bind to the Zif268 site (Figure 2). Overnight growth in a plate reader showed that our selection strain was sensitive enough to detect Zif268 when diluted as low as one to one million in as high a concentration of 3-AT as 10mM. This is more than sufficient to pick out one hit among the 9000 chip-synthesized zinc fingers.

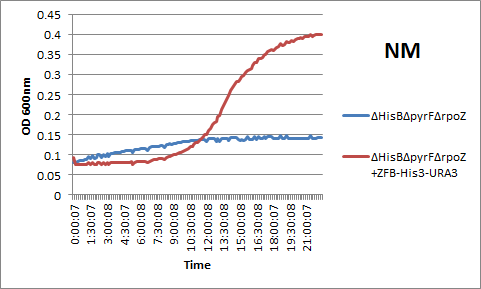

We also wanted to compare our genomic system to the plasmid-based one-hybrid selection used by Meng and others. We accordingly assembled a plasmid with the Zif268 binding site-His3-URA3 construct and transformed it into the ΔHisBΔPyrFΔrpoZ strain with the Zif268-omega subunit fusion protein. After overnight analysis in a plate reader, we observed that the plasmid-based and genomic-based systems produced similar restults: see below for an example of Zif268's rescue of the growth phenotype in incomplete media using the plasmid-based selection.

We designed an additional one-hybrid selection system utilizing TolC, an SDS pump, under the control of a zinc finger binding site. The strain was successfully made and showed the proper phenotypic rescue when Zif268 was present, but SDS concentrations were not as titratable as 3-AT, and it was not able to recognize hits among high background levels as well as the His3-URA3 system. Due to TolC’s inferior sensitivity, we decided to transform the chip-synthesized zinc fingers only into the His3-URA3 selection strain.

References

Xiangdong Meng, Michael H Brodsky, Scot A Wolfe. A bacterial one-hybrid system for determining the DNA-binding specificity of transcription factors. (2005). Nature Biotechnology, 23(8): 988-994. [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v23/n8/pdf/nbt1120.pdf]

"

"