Team:Bielefeld-Germany/SinceAmsterdam

From 2011.igem.org

Contents |

What we improved since the European Regional Jamboree

BPA degradation

Specificity of bisphenol A degradation with E. coli

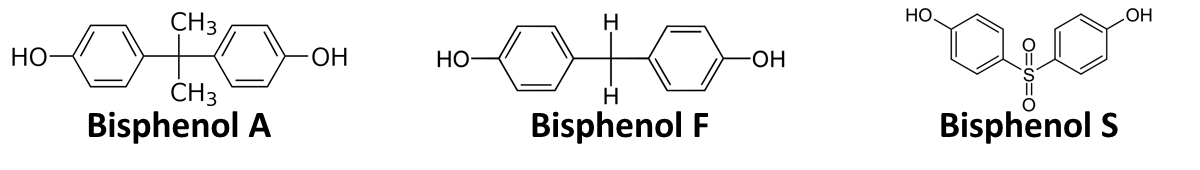

In order to access the specificity of the bisphenol A degradation by the bisdA | bisdB fusion protein we tested how well two similar bisphenols, bisphenol F (BPF) and bisphenol S (BPS), were employed. The structure of those bisphenols differs only in the chemical group linking the two phenols from that of bisphenol A (see Figure 1).

BPF and BPS are used in a broad range of applications that involve the use of polycarbonates or epoxy resins and thus can often be found were BPA is also present. Accordingly their presence is a potential disruptive factor that could lead to a false positive signal with our biosensor. This is especially true for BPS that in some cases is used as a substitute for BPA in baby bottles [http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/18/business/global/18iht-rbog-plastic-18.html]. Studies concerning the environmental pollution with BPF ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0043135401003670 Fromme et al. (2002)]) and the acute toxicity, mutagenicity and estrogenicity of BPF and BPS ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tox.10035/abstract Chen et al. (2001)] and [http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/content/84/2/249 Kitamura et al. (2005)]) indicate their potential harmfulness but further research is needed to fully access their impact on human health.

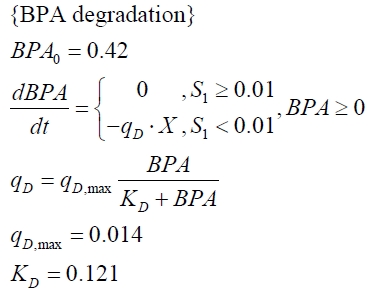

E. coli KRX carrying genes for the bisdA | bisdB fusion protein behind the medium strong constitutive promoter <partinfo>J23110</partinfo> with RBS <partinfo>B0034</partinfo> was cultivated at 30 °C for 36 h with LB-Medium containing 120 mg L-1 BPA, BPF respectively BPS. The BPF and BPS concentration where determined with a HPLC using the same method as with BPA. Figure 2 shows the degradation of the respective bisphenol after 24 h of cultivation in percent.

The results of the experiment indicate that the bisdA | bisdB fusion protein has a high specificity for the degradation of BPA. In addition it is possible that the decrease in BPF and BPS concentration is due to internalization of those bisphenols or a endogenous enzyme of E. coli KRX and not the bisdA | bisdB fusion protein was responsible. It can be assumed that false positive signals because of BPF or BPS present in a sample are unlikely.

BPA degradation with constructs containing FNR

Constructs containing FNR, BisdA and BisdB polycistronic <partinfo>K525551</partinfo>, FNR and a fusion protein of BisdA and BisdB <partinfo>K525582</partinfo> and a fusion protein of FNR, BisdA and BisdB <partinfo>K525560</partinfo> were tested for their ability to degrade BPA. Cultivations were done using the same conditions as with previous constructs. The results are shown in figure 3 below.

The results indicate that the BPA degradation was improved using fusion proteins compared to the completely polycistronic construct. Also the fusion protein of all three enzymes (<partinfo>K525560</partinfo>) involved in the degradation of BPA worked as intended which is quite impressive.

Comparsion of all constructs used for BPA degradation

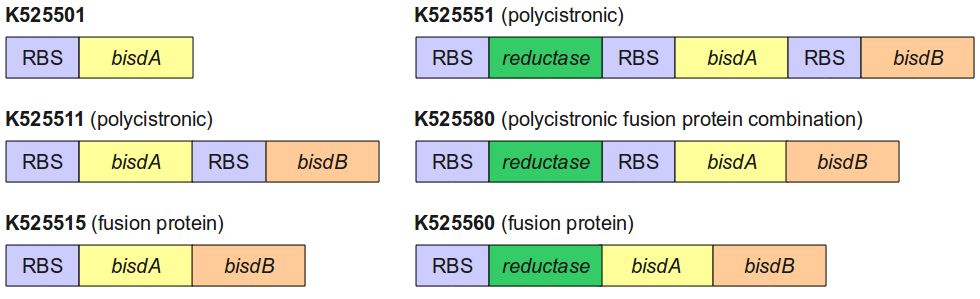

Figure 4 gives an overview of the constructs employed for the degradation of BPA.

All constructs were cultivated under the same conditions as described under Cultivations. BPA concentrations were measured using HPLC. Figure 5 shows the percentage of BPA degraded in 24 h of cultivation and the specific BPA degradation rate calculated with the regular model and in the case of <partinfo>K525560</partinfo> with the model for the fusion protein between FNR, BisdA and BisdB.

We are especially impressed that the fusion protein of FNR, BisdA and BisdB (<partinfo>K525560</partinfo>) not only was capable to degrade BPA but also was the fastest construct we employed. This also contributes to the feasibility of our approach for a cell free BPA biosensor since in a cell free enviroment fusion proteins are beneficial when compared to their non-fused counter parts.

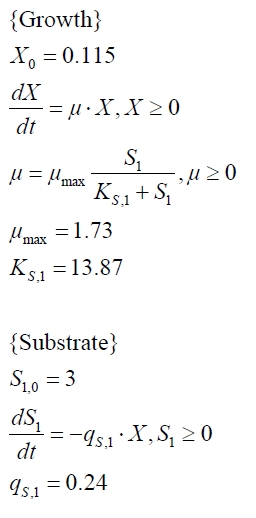

Model for the fusion protein between FNR, BisdA and BisdB

The cultivations and BPA degradation of E. coli KRX carrying a fusion protein consisting of ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase, ferredoxinbisd and cytochrome P450bisd differ from the cultivations with the other BPA degrading BioBricks. Thus, the model for these cultivations has to be adjusted to this behaviour. First of all, no diauxic growth is observed so the growth can be modelled more easily like

The BPA degradation starts when the imaginary substrate is depleted, like observed in the other cultivations with BPA degrading BioBricks. But it seems that the BPA degradation is getting slower with longer cultivation time. So it is modelled with a Monod-like term in which the specific BPA degradation rate is dependent from the BPA concentration:

with the maximal specific BPA degradation rate qD,max and the constant KD.

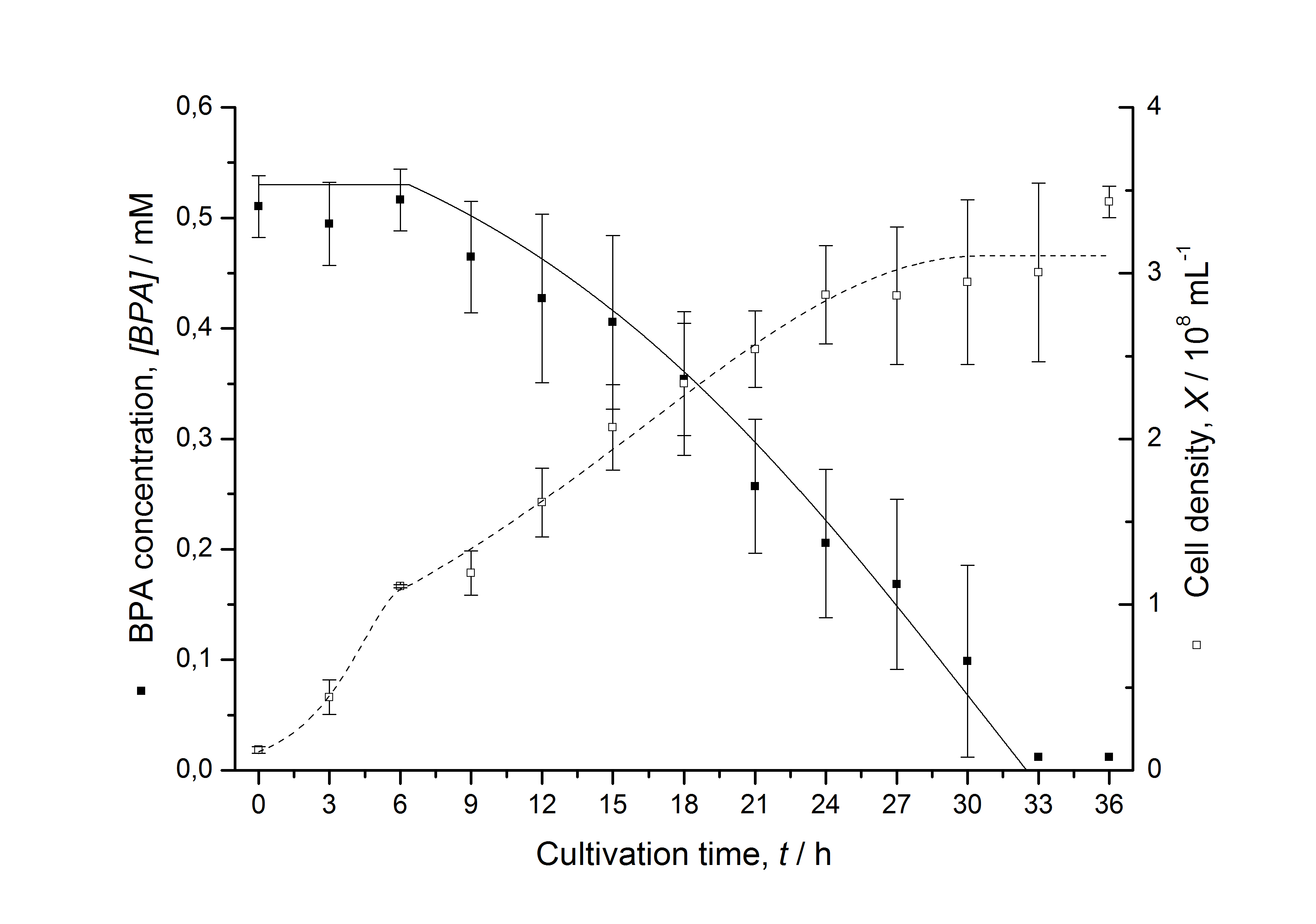

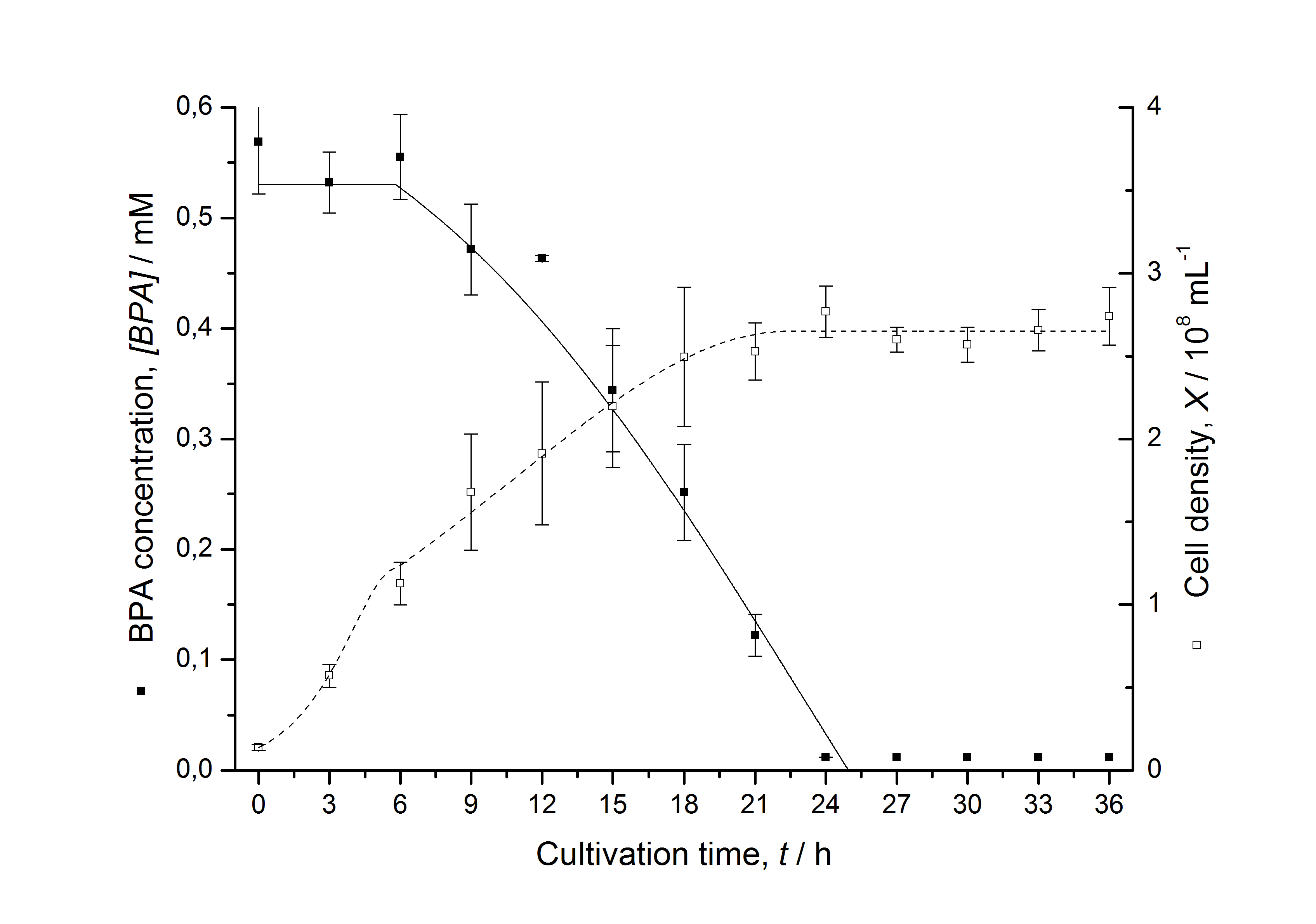

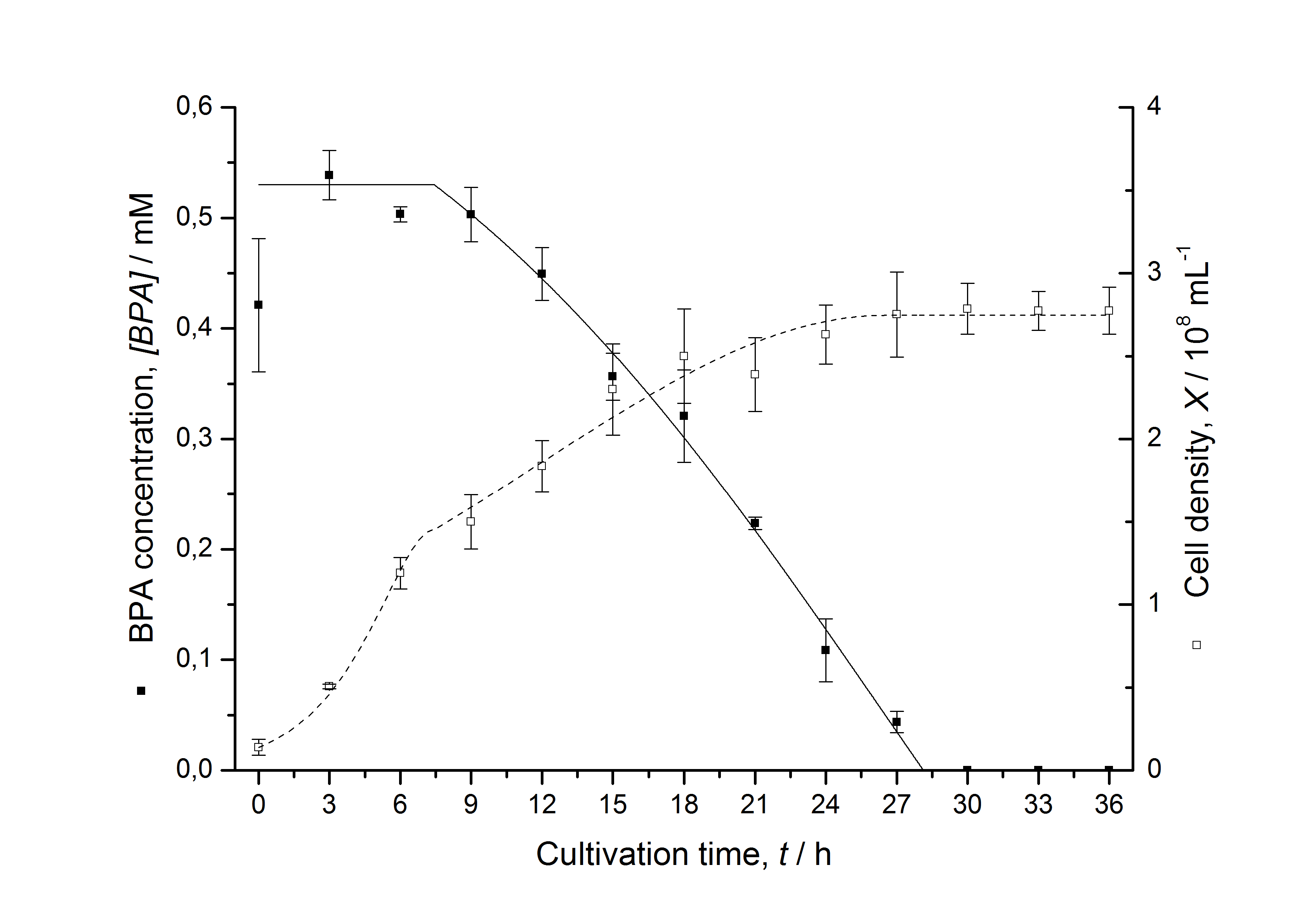

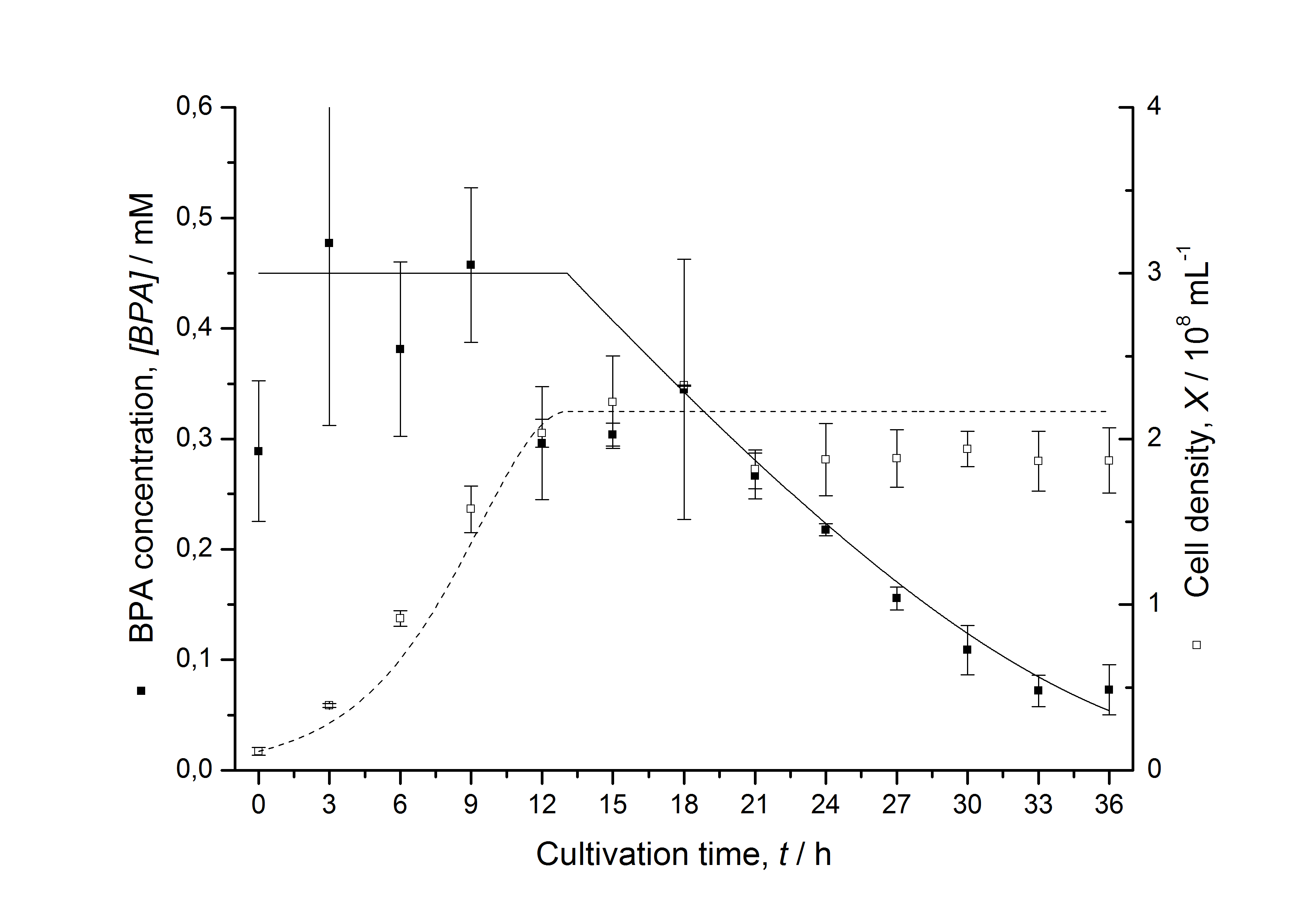

Figures 13 shows a comparison between modelled and measured data for cultivations with BPA degrading fusion protein E. coli. In Tab. 1 the parameters for the model are given, obtained by curve fitting the model to the data.

Comparison between modelled and measured data

Tab. 1: Parameters of the model.

| Parameter | <partinfo>K525512</partinfo> | <partinfo>K525517</partinfo> | <partinfo>K525552</partinfo> | <partinfo>K525562</partinfo> | <partinfo>K525582</partinfo> |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X0 | 0.112 108 mL-1 | 0.138 108 mL-1 | 0.109 108 mL-1 | 0.115 108 mL-1 | 0.139 108 mL-1 |

| µmax | 1.253 h-1 | 1.357 h-1 | 0.963 h-1 | 1.730 h-1 | 0.858 h-1 |

| KS,1 | 2.646 AU-1 | 1.92 AU-1 | 5.35 AU-1 | 13.87 AU-1 | 3.05 AU-1 |

| KS,2 | 265.1 AU-1 | 103.1 AU-1 | 82.6 AU-1 | - | 32.5 AU-1 |

| S1,0 | 1.688 AU | 1.166 AU | 4.679 AU | 3.003 AU | 2.838 AU |

| qS,1 | 0.478 AU 10-8 cell-1 | 0.319 AU 10-8 cell-1 | 0.883 AU 10-8 cell-1 | 0.240 AU 10-8 cell-1 | 0.544 AU 10-8 cell-1 |

| S2,0 | 16.091 AU | 6.574 AU | 3.873 AU | - | 2.402 AU |

| qS,2 | 0.295 AU 10-8 cell-1 | 0.191 AU 10-8 cell-1 | 0.082 AU 10-8 cell-1 | - | 0.056 AU 10-8 cell-1 |

| BPA0 | 0.53 mM | 0.53 mM | 0.41 mM | 0.45 mM | 0.53 mM |

| qD | 8.76 10-11 mM cell-1 | 1.29 10-10 mM cell-1 | 5.67 10-11 mM cell-1 | - | 1.13 10-10 mM cell-1 |

| qD,max | - | - | - | 1.32 10-10 mM cell-1 | - |

| KD | - | - | - | 0.121 mM-1 | - |

The specific BPA degradation rate per cell qD is about 50 % higher when using the fusion protein compared to the polycistronic bisdAB gene. This results in an average 9 hours faster, complete BPA degradation by E. coli carrying <partinfo>K525517</partinfo> compared to <partinfo>K525512</partinfo> as observed during our cultivations. The fusion protein between BisdA and BisdB improves the BPA degradation by E. coli. Introducing a polycistronic ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase gene into these systems does not lead to a higher specific BPA degradation rate. The rates are a bit lower, though. The effect that the BisdA | BisdB fusion protein is more efficient than BisdB when expressed polycistronically with BisdA can still be observed in this setup. The cultivations with the expression of the fusion protein FNR | BisdA | BisdB differ from the expression of the other BPA degrading BioBricks. The BPA degradation rate is concentration dependent which is typical for enzymatic reactions but was not observed in the other cultivations. In addition, the growth was faster and not diauxic. The maximal specific BPA degradation rate of this BioBrick is higher than the observed specific BPA degradation rates in the other cultivations. But due to the dependence of the BPA degradation from the BPA concentration the BPA degradation with this BioBrick is not as efficient and not complete. Anyway, the fact that this BioBrick is working is impressive.

S-layer

Purification???

Enzyme reaction fused to S-layer protein???

???

NAD+ detection

Identification of LigA

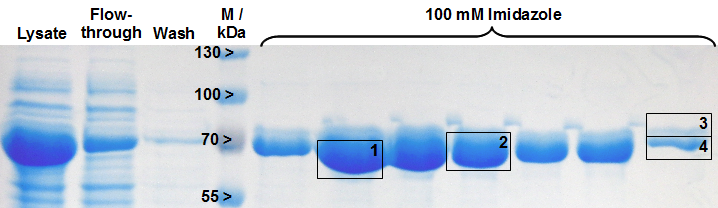

The gel bands after SDS-PAGE for His-tag purified LigA were analysed by MALDI-TOF MS and the comparison with the swissprot database clearly identified the purified protein as LigA (figure 2, table 2). As it is reported in literature the majority of LigA usually occurs in its adenylated form after extraction from E. coli. An indication for this is the double band on the right edge of figure 2. The proteins in both gel bands were identified as LigA from E. coli suggesting that gel band 3 is the adenylated form and gel band 4 is the deadenylated form.

Table 2: Identification of LigA by MALDI-TOF MS. The values correspond to the framed and numbered gel bands in figure 2. The threshold for significance of the Mascot Score for MS is 63 and the one for MS/MS is 26. The MS-Coverage represents the sequence coverage of the investigated protein with the corresponding entry in the E. coli swissprot data base. The Sequence-Coverage shows the percentage of similarity to the translated BioBrick <partinfo>BBa_K525710</partinfo> (translation was perfomed with the [http://web.expasy.org/translate/ ExPASy Translate] tool).

| Number | Method | Swissprot number | Protein | Protein Mascot Score | Protein MW | pI-Value | MS- Coverage [%] | Sequence- Coverage [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MS | B1XA82 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 96 | 73560 | 5.3 | 17 | 25.8 |

| 2 | MS | B1XA82 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 109 | 73560 | 5.3 | 21 | 28.7 |

| 3 | MS | A7ZPL2 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 41 | 73618 | 5.2 | 7 | 10.2 |

| 4 | MS | B1XA82 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 134 | 73560 | 5.3 | 29 | 36.6 |

| 1 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 54 | 73602 | 5.2 | 6 | / |

| 2 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 63 | 73602 | 5.2 | 6 | / |

| 3 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 33 | 73602 | 5.2 | 2 | / |

| 4 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 36 | 73602 | 5.2 | 2 | / |

Limit of detection

Selectivity test

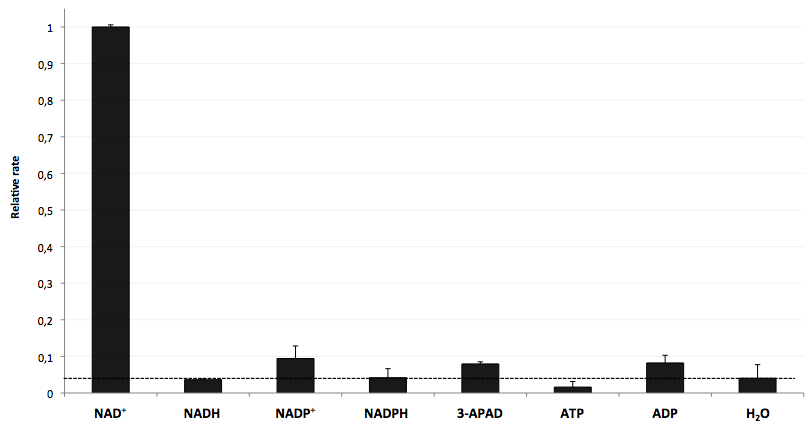

The specifity of LigA for its substrate NAD+ is important in order to couple the NAD+ detection with investigated processes including NADH-dependent enzyme reactions. The verification of the selectivity is an important matter to exclude any unspecific reactions which might result in a NAD+-independent fluorescence enhancement. Hence, a selectivity test for LigA was performed with the analytes NADH, NADP+, NADPH, 3-ADAP (NAD+ with an exchanged functional group at the nicotinamide ring system), ATP and ADP, and the relative fluorescence enhancement rates in a NAD+ bioassay were compared with the one for NAD+ (figure 9).

The negative control (H2O) shows that there was a small background signal about 5 % of the signal that was produced by NAD+ when using 100 nM of analytes. This marks the threshold for fluorescence enhancement which is caused by the employed analyte. NADH, NADPH and ATP were similar to the negative control and can thereby seen as analytes that do not enable DNA ligation by LigA. Only the values for the three analytes NADP+, 3-APAD and ADP were above the threshold, but they were constantly below 10 % of the NAD+ signal. This leads to the suggestion that LigA ist highly selective for NAD+ even in presence of structurally similar analytes. This makes the NAD+ bioassay and the associated enzyme LigA suitable for investigating NADH-dependent enzyme reactions or measuring NAD+ in biological analyte mixtures such as cell lysates.

Coupled enzyme reaction

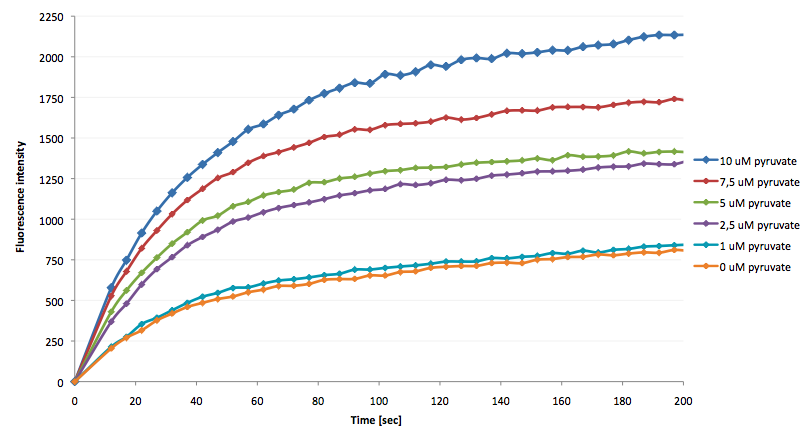

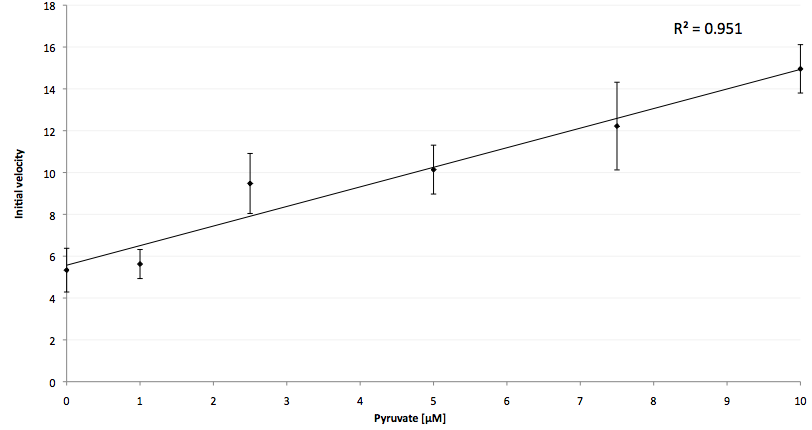

The coupling of the LigA-including NAD+ detection system was performed with a NADH-dependent enzymatic reaction which was in concrete the conversion of pyruvate to L-lactate by lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) from E. coli. For this the LDH reaction was done with an excess of NADH and various pyruvate concentrations. Afterwards, the reaction mix was transferred to a NAD+ bioassay and the fluorescence intensity was monitored. In figure 10 the normalized initial fluorescence enhancement rates for the employed pyruvate concentrations are indicated. The calculated initial velocity was then plotted against the pyruvate concentration (figure 11).

The addition of the LDH reaction mix resulted in a characteristic fluorescence enhancement rate depending on the employed pyruvate concentration. The existing correlation between both parameters seemed to be a linear. That the signal for 0 µM pyruvate was remarkably high could be the result of an pyruvate-independent transfer of electrons from NADH to the active site histidine of LDH under formation of NAD+. The limit of detection for pyruvate seemed to be near 1 µM pyruvate. That this value was not in nano molarity scale is firstly caused by 100-fold dilution of the LDH reaction mix after addition to the NAD+ bioassay and secondly by the fact that LDH does not necessarily converte 100 % of the pyruvate to L-lactate. Nevertheless, for the LigA based NAD+ detection system it has been proven that it can be coupled to NADH-dependent enzymatic reactions. This makes the NAD+ bioassay suitable for a wide range of biological studies dealing with the ubiquitous cofactors NADH/NAD+.

Molecular cloning

Because DNA ligase from E. coli is commercially aquirable for cloning purposes LigA (<partinfo>BBa_K525710</partinfo>) was tested whether it is also suitable for molecular cloning procedures. Hence, cloning of rfp into a pSB1C3 vector was performed with LigA. Ligation was done with NAD+ bioassay buffer containing 10 mM NAD+ at 37 °C or 22 °C and the vectors were transformed into E. coli KRX by electroporation. After growth over night at 37 °C on petri dishes the results were documented (figure 12).

By analyzing the number of colony forming units and color of the colonies the ligation efficiency of LigA should be assessable. As shown for the sample without any ligase there were only a few clones able to grow on chloramphenicol supplemented LB medium. A much bigger number of clones was observed when ligation by LigA was performed at 22 °C. Furthermore, there were a lot of red colonies indicating positive clones. Deductively, LigA might be useful for (large-scale) molecular cloning procedures which could be beneficial because of its easy production in E. coli and simple purification.

"

"