Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/NAD

From 2011.igem.org

Contents |

Important parameters

Table 1: Parameters for NAD+-dependent DNA ligase from E. coli (LigA). The parameters number of amino acids, molecular weight, theoretical pI and extinction coefficient were calculated with the help of the [http://web.expasy.org/translate/ ExPASy Translate] tool and the [http://web.expasy.org/protparam/ Expasy ProtParam] tool.

| Experiment | Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Expression | ||

| Compatibility | E. coli KRX | |

| Promoter | PT7 | |

| Inductor of expression | L-rhamnose for induction of T7 polymerase | |

| Optimal temperature | 37 °C | |

| Purification | ||

| Number of amino acids | 678 | |

| Molecular weight | 74.59 kDa | |

| Theoretical pI | 5.59 | |

| Extinction coefficient at 280 nm measured in water [M-1 cm-1] | 37400 (assuming all pairs of Cys residues form cystines)

36900 (assuming all Cys residues are reduced) | |

| Tag | C-terminal 6xHis | |

| NAD+ detection | ||

| Limit of detection | 2 nM |

Purification and identification of LigA

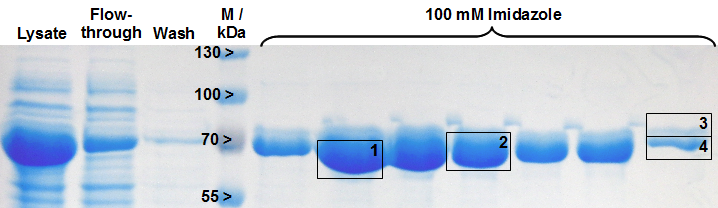

Expression of LigA in E. coli is an easy approach to produce the recombinant protein LigA in large scale. The protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % rhamnose. Cell harvest was performed after 4 h further growth at 37 °C. After enzymatic cell lysis the protein could be purified with the help of Ni-NTA columns utilizing the proteins C-terminal His-tag. As shown in figure 1 the majority was eluted with 100 mM imidazole. The gel bands were analysed by MALDI-TOF MS and comparison with the swissprot database clearly identified the purified protein as LigA (figure 2, table 2).

Table 2: Identification of LigA by MALDI-TOF MS. The values correspond to the framed and numbered gel bands in figure 2. The threshold for significance of the Mascot Score for MS is 63 and the one for MS/MS is 26.

| Number | Method | Swissprot number | Protein | Protein Mascot Score | Protein MW | pI-Value | MS- Coverage [%] | Sequence- Coverage [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MS | B1XA82 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 96 | 73560 | 5.3 | 17 | 25.8 |

| 2 | MS | B1XA82 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 109 | 73560 | 5.3 | 21 | 28.7 |

| 3 | MS | A7ZPL2 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 41 | 73618 | 5.2 | 7 | 10.2 |

| 4 | MS | B1XA82 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 134 | 73560 | 5.3 | 29 | 36.6 |

| 1 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 54 | 73602 | 5.2 | 6 | / |

| 2 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 63 | 73602 | 5.2 | 6 | / |

| 3 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 33 | 73602 | 5.2 | 2 | / |

| 4 | MS/MS | Q0TF55 | DNA ligase OS=Escherichia coli GN=ligA | 36 | 73602 | 5.2 | 2 | / |

As it is reported in literature the majority of LigA usually occurs in its adenylated form after extraction from E. coli. An indication for this is the double band on the right edge of figure 2. The proteins in both gel bands were identified as LigA from E. coli suggesting that gel band 3 is the adenylated form and gel band 4 is the deadenylated form. Depending on whether the protein should be in its deadenylated form for further applications a treatment with an excess of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) for deadenylation is possible.

NAD+ detection

LigA can be applied to a molecular beacon based bioassay detecting NAD+ even in very low concentrations. For this two important requirements have to be fulfilled: the purified LigA has to be in its deadenylated form so that DNA ligation occurs only in presence of NAD+. Furthermore, molecular beacons have to be designed appropriately so that they stay in their closed state under the chosen conditions and after hybridization to a split target. The molecular beacon is supposed to form its open state resulting in an increase of fluorescence intensity not before LigA ligates the split target in a NAD+-dependent manner.

The proof for a valid NAD+ detection system which has been used for characterization of LigA is shown in figures 3 and 4. The molecular beacon formed its open state after hybridization to a complementary target so that the close proximity of the fluorophor and the quencher broke up. After excitation with light a 45.52-fold increase in fluorescence intensity compared to the background signal (molecular beacon alone) could be determined. By contrast, this was not the case after using a complementary split target hybridzied to the molecular beacon because the signal-to-background ratio was just 3.36. This shows that the split target was not able to reach the molecular beacons open state, but the complete target did so. Thus, this approach is useful to measure LigA activity and therefore detect NAD+.

For the NAD+ bioassay the molecular beacon was preincubated with the split target at 37 °C. After the fluorescence intensity reached equilibrium purified and deadenylated LigA was added in a final concentration of 5 ng/µL followed by NAD+ addition (figure 5). First of all, there was only little increase in fluorescence intensity after LigA addition indicating that the pretreatment with NMN for deadenylation was successful. In a separate experiment with LigA that was not pretreated with NMN a continous increase in fluorescence intensity was observed (data not shown). This leads to the suggestion that an excess of NMN supports deadenylation reaction of LigA which makes the enzyme suitable for NAD+ detection. After NAD+ addition the fluorescence intensity increased distinctly while the fluorescence enhancement rate was dependent on the employed NAD+ concentration. This phenomenon is illustrated in figure 6 which describes the fluorescence increase after normalization of all fluorescence values to the first measured value for each measurement series (NAD+ concentration) from figure 5.

As expected the initial enhancement rate of fluorescence intensity reached almost saturation as soon as using NAD+ concentrations higher then 250 nM which matched the employed molecular beacon concentration. In this case the molecular beacon, the second substrate for LigA, ought to be the limiting factor for the enzymatic reaction, but not the NAD+ which is supposed to be detected. Anyway, there seems to exist a linear dependence for the NAD+ concentration and the initial enhancement rate of fluorescence for NAD+ concentrations below the molecular beacon concentration. This is shown in figure 7 in which the linear dependence is indicated by linear regression of the data. As you can see the NAD+ concentration correlates with the average of fluorescence enhancement rate in 200 s after NAD+ addition (initial velocity) in a linear way as long as the NAD+ concentration was kept below the systems capacity. This means that a specific fluorescence enhancemant rate is characteristic for a particular NAD+ concentration caused by a fixed affinity of LigA and NAD+ as a limiting substrate for DNA ligation. Referring to this, the minimal detected NAD+ concentration was 2 nM.

The fluorescence intensity enhancement is supposed to be caused by LigA ligating the split target in a NAD+-dependent manner. This becomes clearly first due to the absence of fluorescence intensity increase for the negative control (0 nM NAD+) and second due to the lengthy fluorescence enhancement after NAD+ addition suggesting enzymatic activity by LigA. This could be directly visualized by taking pictures of the reactions endpoint. As illustrated in figure 8 the fluorescence intensity for added LigA and NAD+ reached nearly the same level as for the positive control (complete target). This was not the case when NAD+ was missing in the reaction mix with LigA and the split target.

Selectivity test

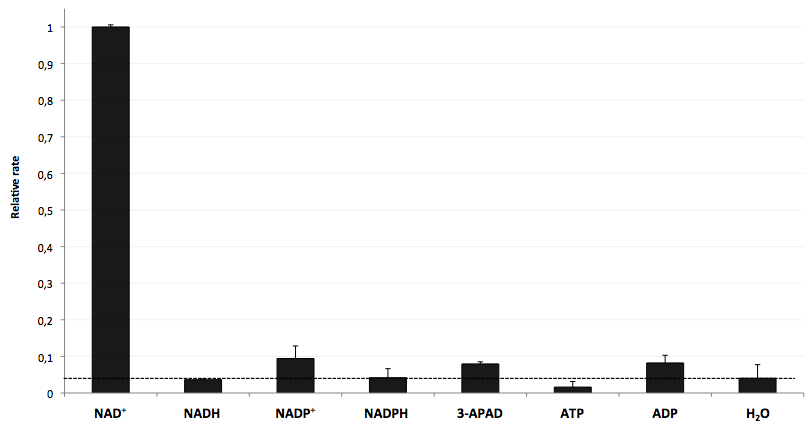

The specifity of LigA for its substrate NAD+ is important in order to couple the NAD+ detection with investigated processes including NADH-dependent enzyme reactions. The verification of the selectivity is an important matter to exclude any unspecific reactions which might result in a NAD+-independent fluorescence enhancement. Hence, a selectivity test for LigA was performed with the analytes NADH, NADP+, NADPH, 3-ADAP (NAD+ with an exchanged functional group at the nicotinamide ring system), ATP and ADP, and the relative fluorescence enhancement rates in a NAD+ bioassay were compared with the one for NAD+ (figure 9).

The negative control (H2O) shows that there was a small background signal about 5 % of the signal that was produced by NAD+ when using 100 nM of analytes. This marks the threshold for fluorescence enhancement which is caused by the employed analyte. NADH, NADPH and ATP were similar to the negative control and can thereby seen as analytes that do not enable DNA ligation by LigA. Only the values for the three analytes NADP+, 3-APAD and ADP were above the threshold, but they were constantly below 10 % of the NAD+ signal. This leads to the suggestion that LigA ist highly selective for NAD+ even in presence of structurally similar analytes. This makes the NAD+ bioassay and the associated enzyme LigA suitable for investigating NADH-dependent enzyme reactions or measuring NAD+ in biological analyte mixtures such as cell lysates.

Coupled enzyme reaction

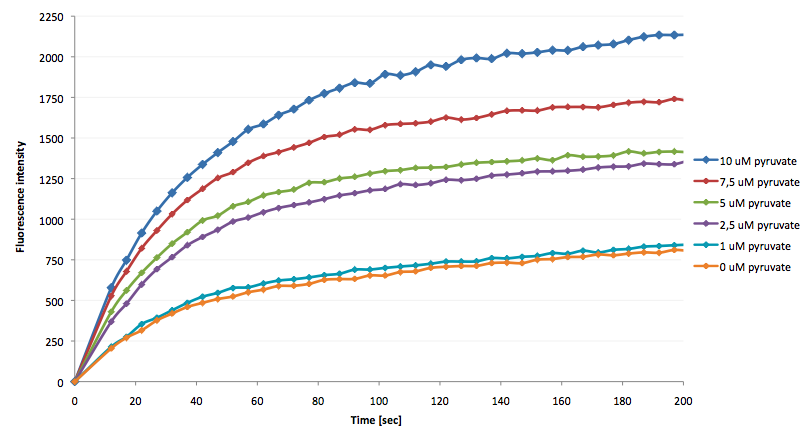

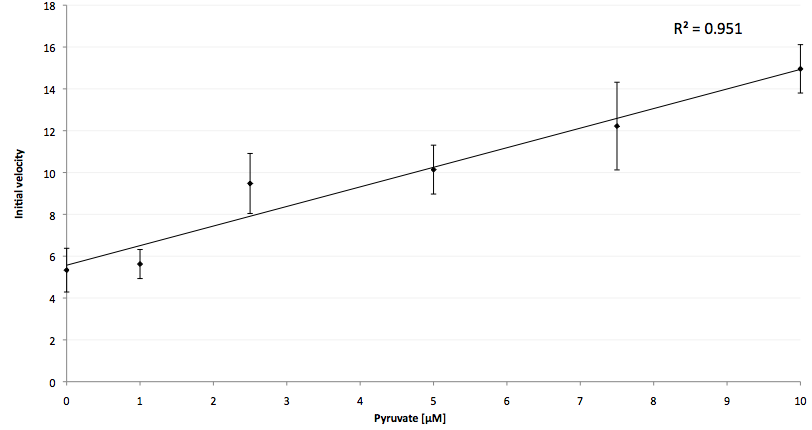

The coupling of the LigA-including NAD+ detection system was performed with a NADH-dependent enzymatic reaction which was in concrete the conversion of pyruvate to L-lactate by lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) from E. coli. For this the LDH reaction was done with an excess of NADH and various pyruvate concentrations. Afterwards, the reaction mix was transferred to a NAD+ bioassay and the fluorescence intensity was monitored. In figure 10 the normalized initial fluorescence enhancement rates for the employed pyruvate concentrations are indicated. The calculated initial velocity was then plotted against the pyruvate concentration (figure 11).

The addition of the LDH reaction mix resulted in a characteristic fluorescence enhancement rate depending on the employed pyruvate concentration. The existing correlation between both parameters seemed to be a linear. That the signal for 0 µM pyruvate was remarkably high could be the result of an pyruvate-independent transfer of electrons from NADH to the active site histidine of LDH under formation of NAD+. The limit of detection for pyruvate seemed to be near 1 µM pyruvate. That this value was not in nano molarity scale is firstly caused by 100-fold dilution of the LDH reaction mix after addition to the NAD+ bioassay and secondly by the fact that LDH does not necessarily converte 100 % of the pyruvate to L-lactate. Nevertheless, for the LigA based NAD+ detection system it has been proven that it can be coupled to NADH-dependent enzymatic reactions. This makes the NAD+ bioassay suitable for a wide range of biological studies dealing with the ubiquitous cofactors NADH/NAD+.

Molecular cloning

Because DNA ligase from E. coli is commercially aquirable for cloning purposes LigA (<partinfo>BBa_K525710</partinfo>) was tested whether it is also suitable for molecular cloning procedures. Hence, cloning of rfp into a pSB1C3 vector was performed with LigA. Ligation was done with NAD+ bioassay buffer containing 10 mM NAD+ at 37 °C or 22 °C and the vectors were transformed into E. coli KRX by electroporation. After growth over night at 37 °C on petri dishes the results were documented (figure 12).

By analyzing the number of colony forming units and color of the colonies the ligation efficiency of LigA should be assessable. As shown for the sample without any ligase there were only a few clones able to grow on chloramphenicol supplemented LB medium. A much bigger number of clones was observed when ligation by LigA was performed at 22 °C. Furthermore, there were a lot of red colonies indicating positive clones. Deductively, LigA might be useful for (large-scale) molecular cloning procedures which could be beneficial because of its easy production in E. coli and simple purification.

Conclusions

LigA, the NAD+-dependent DNA ligase from E. coli (<partinfo>BBa_K525710</partinfo>), can be utilized for a molecular beacon based bioassay detecting NAD+ in nano molarity scale (limit of detection: 2 nM). It has been shown that the NAD+ concentration determines the initial fluorescence enhancement rate as a result of ligation of the nicked DNA substrate (250 nM molecular beacon hybridized to a split target). There is a linear dependence for both parameters while the NAD+ concentration is kept below the molecular beacon concentration. By varying the molecular beacon concentration the range for linear dependence of NAD+ concentration and initial velocity of LigA might be expandable. Furthermore, LigA shows a high selectivity for NAD+ which means that DNA ligation upon NADH consumption does not occur in a measurable manner. This enables NAD+ detection even in presence of structurally similar analytes like NADH, NADP+, NADPH, 3-ADAP, ATP or ADP. By meeting this requirements the NAD+ bioassay is suitable for investigations of coupled NADH-dependent enzyme reactions and monitoring of NAD+ pools in cell lysates. Finally, LigA seems to be suitable as a model system for bacterial DNA ligases due to the highly conserved functional domains throughout the bacterial kingdom. This could be useful in terms of antibiotic drug design utilizing the bacterial DNA ligases specifity for NAD+ as a cofactor.

References

Gajiwala KS, Pinko C (2004) Structural Rearrangement Accompanying NAD+ Synthesis within a Bacterial DNA Ligase Crystal, [http://www.cell.com/structure/abstract/S0969-2126%2804%2900235-7 Structure 12(8):1449-1459].

Miesel L, Kravec C, Xin AT, McMonagle P, Ma S, Pichardo J, Feld B, Barrabee E, Palermo R (2007) High-throughput assay for the adenylation reaction of bacterial DNA ligase, [http://medical-journals.healia.com/doc/17493575/A-high-throughput-assay-for-the-adenylation-reaction-of-bacterial-DNA-ligase Analytical Biochemistry 366:9-17].

Nandakumar J, Nair PA, Shuman S (2007) Last Stop on the Road to Repair: Structure of E. coli DNA Ligase Bound to Nicked DNA-Adenylate, [http://www.cell.com/molecular-cell/abstract/S1097-2765%2807%2900144-X Molecular Cell 26(2):257-271].

Tang Z, Liu P, Ma C, Yang X, Wang K, Tan W, Lv X (2011) Molecular Beacon Based Bioassay for Highly Sensitive and Selective Detection of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide and the Activity of Alanine Aminotransferase, [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ac102742k Anal Chem 83(7):2505-2510].

Tyagi S, Kramer FR (1996) Molecular beacons: probes hat fluoresce upon hybridization, [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v14/n3/abs/nbt0396-303.html Nature Biotechnology 14:303-308].

"

"