Modelling

Contents |

Mathematical modelling: introduction

Mathematical modelling plays nowadays a central role in Synthetic Biology, due to its ability to serve as a crucial link between the concept and realization of a biological circuit: what we propose in this page is a modelling approach to our project, which has proven extremely useful and very helpful before and after the "wet lab".

Thus, immediately at the beginning, when there was little knowledge, a mathematical model based on a system of differential equations was derived and implemented using a set of parameters, to validate the feasibility of the project. Once this became clear, starting from the characterization of the single subparts created in the wet lab, some of the parameters of the mathematical model were estimated (the others are known from literature) and they have been fixed to simulate the same model, in order to predict the final behaviour of the whole engineered closed-loop circuit. This approach is consistent with the typical one adopted for the analysis and synthesis of a biological circuit, as exemplified by Pasotti et al 2011.

Therefore here, after a brief overview about the advantages that modelling engineered circuits can bring, we deeply analyze the system of equation formulas, underlining the role and function of the parameters involved.

Experimental procedures for parameter estimation are discussed and, finally, a different type of circuit is presented. Simulations were performed, using ODEs with MATLAB and used to explain the difference between a closed-loop control system model and an open one.

The importance of mathematical modelling

Mathematical modeling reveals fundamental in the challenge for understanding and engineering complex biological systems. Indeed, these are characterized by a high degree of interconnection among the single constituent parts, requiring a comprehensive analysis of their behavior through mathematical formalisms and computational tools

- Simulation: mathematical models allow to analyse complex system dynamics and to reveal the relationships between the involved variables, starting from the knowledge of the behavior of single subparts and from simple hypotesis of their interconnection. (Endler et al, 2009)

- Knowledge elicitation: mathematical models summarize into a small set of parameters the results of several experiments (parameter identification), allowing a robust comparison among different experimental conditions and providing an efficient way to synthesize knowledge about biological processes. Then, through the simulation process, they make possible the re-usability of the knowledge coming from different experiments, engineering complex systems from the composition of its constituent subparts under appropriate experimental/environmental conditions (Braun et al, 2005; Canton et al, 2008)..

Equations for gene networks

|

Hypothesis of the model

|

HP1: In order to better investigate the range of dynamics of each subparts, every promoter has been

studied with 4 different RBSs, so as to develop more knowledge about the state variables in several configurations

of RBS' efficiency. Hereafter, referring to the notation "RBSx" we mean, respectively,

RBS30,

RBS31,

RBS32,

RBS34^top

Equations (1) and (2)Equations (1) and (2) have identical structure, differing only in the parameters involved. They represent the synthesis degradation and diluition of both the enzymes in the circuit, LuxI and AiiA, respectively in the first and second equation: in each of them both transcription and translation processes have been condensed. The corresponding mathematical formalism is analogous to the one used by Pasotti et al 2011, Suppl. Inf., even if we do not take LuxR-HSL complex formation into account, as explained below. These equations are composed of 2 parts:

Equation (3)Here the kinetics of HSL is modeled, through enzymatic reactions either related to the production or the degradation of HSL: based on the experiments performed, we derived appropriate expressions for HSL synthesis and degradation. This equation is composed of 3 parts:

Equation (4)This is the common logistic population cells growth, depending on the rate μ and the maximum number Nmax of cells per well reachable.

Table of parameters and species

Parameter CV

Parameter estimationThe philosophy of the model is to predict the behavior of the final closed loop circuit starting from the characterization of single BioBrick parts through a set of well-designed ad hoc experiments. Relating to these, in this section the way parameters of the model have been identified is presented.

As explained before in HP1, considering a set of 4 RBS for each subpart expands the range of dynamics and helps us to better understand the interactions between state variables and parameters.

Promoter (PTet & pLux)

These were the first subparts tested.

In this phase of the project the target is to learn more about promoter pTet and pLux. Characterizing promoters only is a very hard task: for this reason we considered promoter and each RBS from the RBSx set as a whole (reference to HP1).

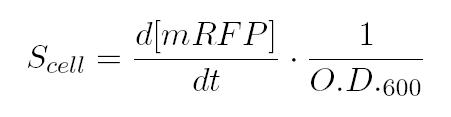

As shown in the figure below, we considered a range of inductions and we monitored, in time, absorbance (O.D. stands for "optical density") and fluorescence; the two vertical segments for each graph highlight the exponential phase of bacterial growth. Scell (namely, synthesis rate per cell) can be derived as a function of inducer concentration, thereby providing the desired input-output relation (inducer concentration versus promoter+RBS activity), which was modelled as a Hill curve:   T9002 introduction

AiiA & LuxI This paragraph explains how parameters of equation (3) are estimated. The target is to learn the AiiA and LuxI degradation and production mechanisms in addition to HSL intrinsic degradation, in order to estimate Vmax, kM,LuxI, kcat and kM,AiiA parameters. These tests have been performed using the following BioBrick parts:

By now, parameter identification about promoters has already been performed. Furthermore, as explained before, the HP4 is also valid in this case.

So, our idea is to control the degradation of HSL in time. ATc activates pTet and, later, a certain concentration of HSL is introduced. Then, at fixed times, O.D.600 and HSL concentration are monitored using Tecan and T9002 biosensor.

NThe parameters Nmax and μ can be calculated from the analysis of the OD600 produced by our MGZ1 culture. In particular, μ is derived as the slope of the log(O.D.600) growth curve. Counting the number of cells of a saturated culture would be considerably complicated, so Nmax is determined with a proper procedure. The aim here is to derive the linear proportional coefficient Θ between O.D'.600 and N: this constant can be estimated as the ratio between absorbance (read from TECAN) and the respective number of CFU on a petri plate. Finally, Nmax is calcultated as Θ*O.D'.600.

(Pasotti et al, 2010).

Degradation ratesThe parameters γLuxI and γAiiA are taken from literature since they contain LVA tag for rapid degradation. Instead, approximating HSL kinetics as a decaying exponential, γHSL can be derived as the slope of the log(concentration), which can be monitored through BBa_T9002.

Simulations

On a biological level, the ability to control the concentration of a given molecule reveals itself as fundamental in limiting the metabolic burden of the cell; moreover, in the particular case of HSL signalling molecules, this would give the possibility to regulate quorum sensing-based population behaviours. In this section we present some simulations of another circuit, which could validate the concept of the closed-loop model we have discussed so far.

In order to see that, we implemented and simulated in Matlab an open loop circuit, similar to CTRL+E, except for the constitutive production of AiiA.

Sensitivity Analysis of the steady state of enzyme expression in exponential phaseIn this paragraph we want to theoretically investigate our circuit behaviour in cell's culture exponential growth phase. According to this, we first derive, under feasible hypoteses, the steady state condition for our enzymes concentration. Then we perform a sensitivity analysis relating the output of our system (HSL) to input (atc) and system parameters. Steady state of enzyme expressionReferences

Kelly JR, Rubin AJ, Davis JH et al. (2009) Measuring the activity of BioBrick promoters using an in vivo reference standard. J. Biol. Eng. 3:4. Salis H M, Mirsky E A, Voight C A (2009)Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat. Biotechnol.27:946-950. |

"

"