Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/S-Layer/CspB CG

From 2011.igem.org

(→CspB from Corynebacterium glutamicum) |

(→CspB from Corynebacterium glutamicum) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

[[File:Bielefeld2011_hexagonal_structure_slayer.png|350px|thumb|right|Fig.1: Different structures of S-layer lattices.]] | [[File:Bielefeld2011_hexagonal_structure_slayer.png|350px|thumb|right|Fig.1: Different structures of S-layer lattices.]] | ||

| - | The S-layer of the gram-positive bacterium ''Corynebacterium glutamicum'' ATCC 14067 is formed by the PS2 (alternatively CspB) protein. The protein is encoded by the gene ''cspB''. The mature protein has a molecular mass of 52.5 kDa. It is devoid of any sulfur-containing amino acids, whereas its nature is due to a high content of hydrophobic amino acids. Although | + | The S-layer of the gram-positive bacterium ''Corynebacterium glutamicum'' ATCC 14067 is formed by the PS2 (alternatively CspB) protein. The protein is encoded by the gene ''cspB''. The mature protein has a molecular mass of 52.5 kDa. It is devoid of any sulfur-containing amino acids, whereas its nature is due to a high content of hydrophobic amino acids. Although a lot of different S-layer proteins exist, PS2 has no similarities to any other protein in the EMBL database. The S-layer of ''C. glutamicum'' is characterized by a hexagonal lattice symmetry (see fig. 1). Attachment between S-layer and cell wall was found to be due to the hydrophobic carboxy-terminus of the PS2 protein. It was found that peptidoglycan is probably not involved in interaction between the PS2 S-layer and the cell because the interaction between PS2 and the cell is disrupted by adding detergents. Also the S-layer protein from ''C. glutamicum'' does not contain a SLH domain, which is characteristic for several S-layer proteins and other enzymes bound to peptidoglycan. Besides, some other S-layer proteins show a carboxy-terminal hydrophobic sequence of 20 – 24 amino acids. (''e.g. Halobacterium halobium, Haloferax volcanii, Rickettsia rickettsii'') ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.d01-1868.x/abstract Chami ''et al.'', 1997], [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016816560400241X Hansmeier ''et al.'', 2004]). |

<br style="clear: both" /> | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

Revision as of 01:00, 29 October 2011

Contents |

CspB from Corynebacterium glutamicum

The S-layer of the gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 14067 is formed by the PS2 (alternatively CspB) protein. The protein is encoded by the gene cspB. The mature protein has a molecular mass of 52.5 kDa. It is devoid of any sulfur-containing amino acids, whereas its nature is due to a high content of hydrophobic amino acids. Although a lot of different S-layer proteins exist, PS2 has no similarities to any other protein in the EMBL database. The S-layer of C. glutamicum is characterized by a hexagonal lattice symmetry (see fig. 1). Attachment between S-layer and cell wall was found to be due to the hydrophobic carboxy-terminus of the PS2 protein. It was found that peptidoglycan is probably not involved in interaction between the PS2 S-layer and the cell because the interaction between PS2 and the cell is disrupted by adding detergents. Also the S-layer protein from C. glutamicum does not contain a SLH domain, which is characteristic for several S-layer proteins and other enzymes bound to peptidoglycan. Besides, some other S-layer proteins show a carboxy-terminal hydrophobic sequence of 20 – 24 amino acids. (e.g. Halobacterium halobium, Haloferax volcanii, Rickettsia rickettsii) ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.d01-1868.x/abstract Chami et al., 1997], [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016816560400241X Hansmeier et al., 2004]).

CspB with TAT-sequence and lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

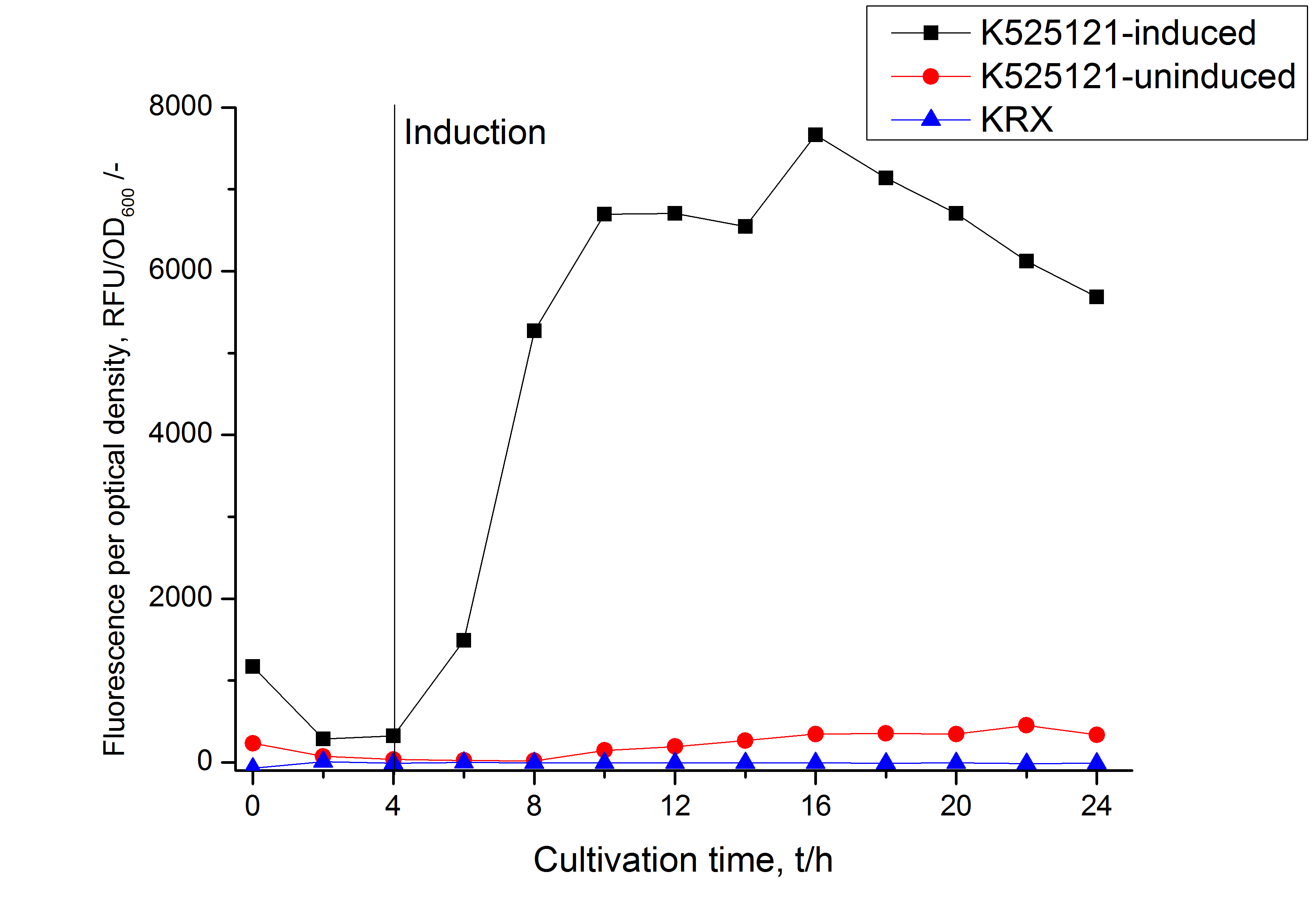

For characterization, CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525121 (K525121)] was fused with a monomeric RFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] using Gibson assembly.

The mRFP|CspB fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0.1 % L-rhamnose using the autoinduction protocol.

Identification and localization

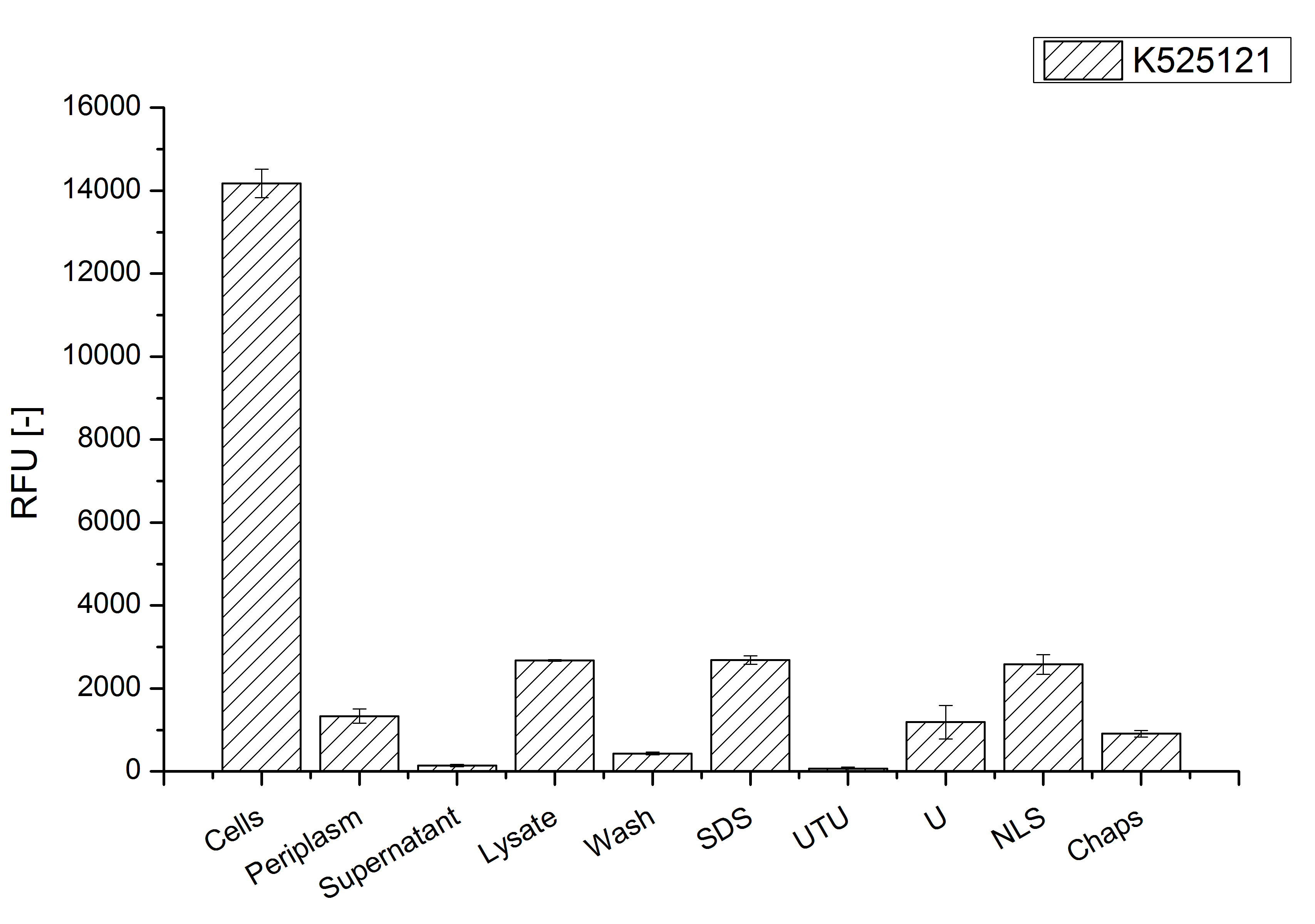

After a cultivation time of 18 h the mRFP|CspB fusion protein should be localized in E. coli KRX. Therefore a part of the produced biomass was mechanically disrupted and the resulting lysate was washed with ddH2O. The periplasm was detached by using a osmotic shock from other parts of the cells. The existance of fluorescene in the periplasm fraction, showed in fig. 4, indicates that C. glutamicum TAT-signal sequence is at least in part functional in E. coli KRX.

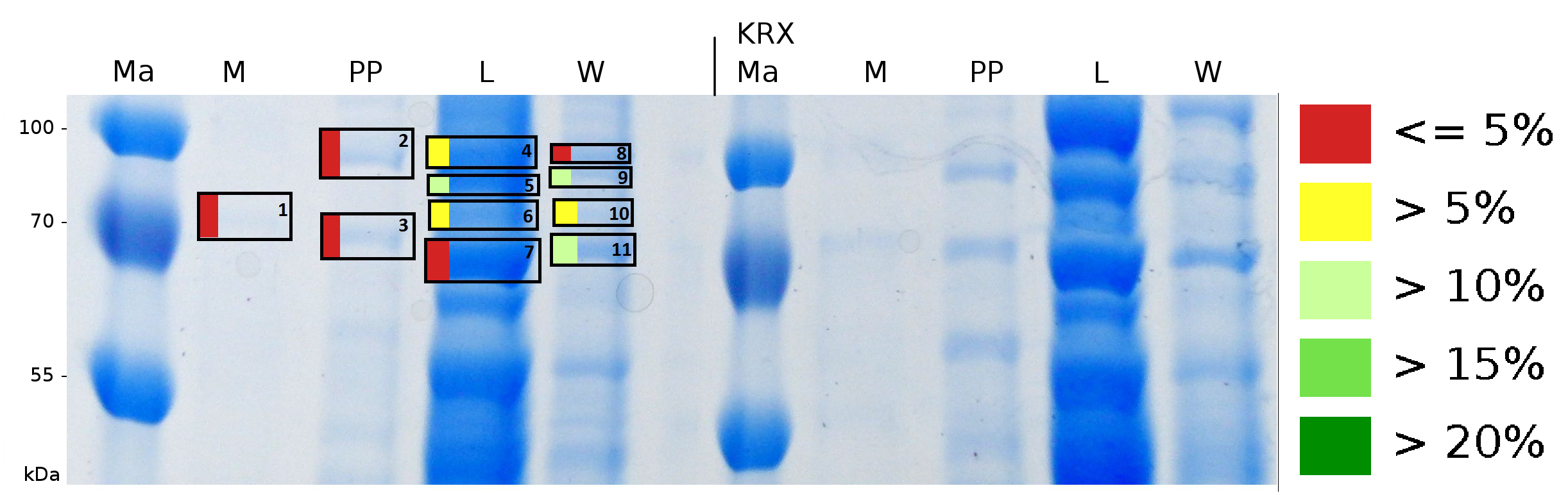

The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the lysate by SDS-PAGE and the cell debris were still red. This indicates that the fusion protein integrates into the cell membrane with the lipid anchor. For testing this assumption the washed lysate was treated with ionic, nonionic and zwitterionic detergents to release the mRFP|CspB out of the membranes.

The existance of fluorescence in the detergent fractions and the proportionally low fluorescence in the wash fraction compared to the lysis fraction confirm the hypothesis of an insertion into the cell membrane (fig. 4). An insertion of these S-layer proteins might stabilize the membrane structure and increase the stability of cells against mechanical and chemical treatment. A stabilization of E. coli expressing S-layer proteins was described by [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20829284 Lederer et al., (2010)].

An other important fact is, that there is actually mRFP fluorescence measurable in such high concentrated detergent solutions. The S-layer seems to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP. The MALDI-TOF analysis of the relevant size range in the polyacrylamid gel approved the existance of the intact fusion protein in all detergent fractions (fig. 5).

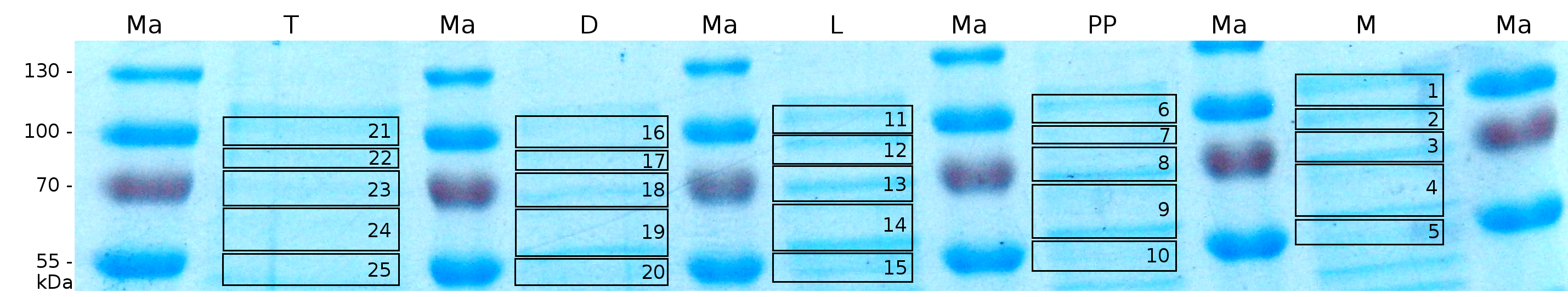

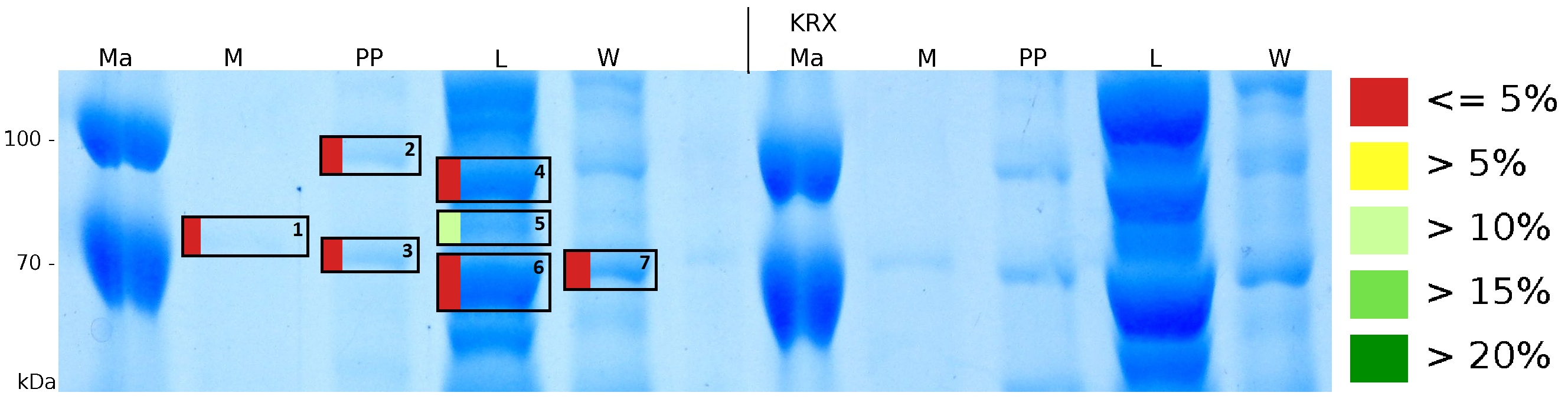

MALDI-TOF analysis was first used to identify the location of the fusion protein in different fractions. Fractions of medium supernatant after cultivation, periplasmatic isolation, cell lysis, denaturation in 6 M urea and the following wash with 2 % (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 % SDS (w/v) were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE and fragments of the gel were measured with MALDI-TOF.

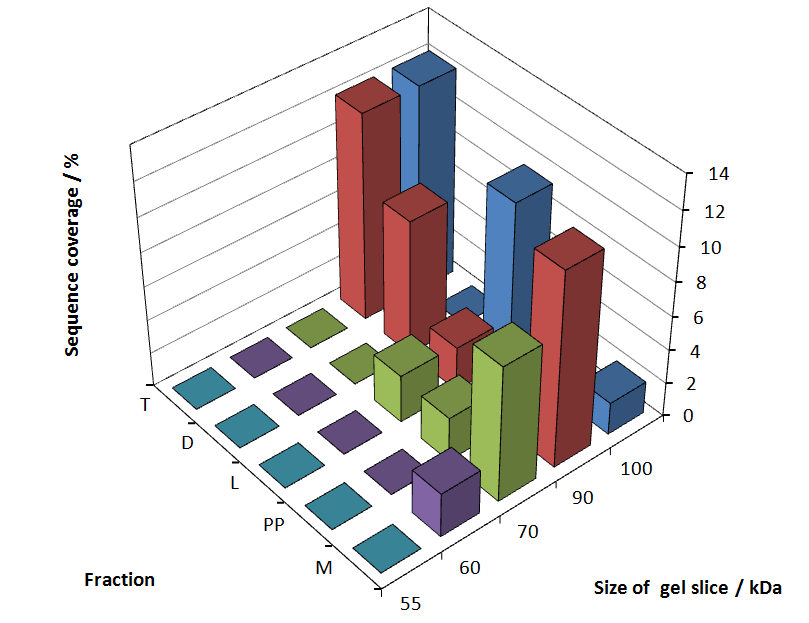

The following table shows the sequence coverage (in %) of our measurable gel samples with the amino acid sequence of fusion protein CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)].

| number of gel sample | sequence coverage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.9 | |

| 2 | 11.5 | |

| 3 | 8.0 | |

| 4 | 2.6 | |

| 5 | 0.0 | |

| 6 | 0.0 | |

| 7 | 2.6 | |

| 8 | 0.0 | |

| 9 | 0.0 | |

| 10 | 0.0 | |

| 11 | 9.4 | |

| 12 | 2.6 | |

| 13 | 2.8 | |

| 14 | 0.0 | |

| 15 | 0.0 | |

| 16 | 0.0 | |

| 17 | 8.0 | |

| 18 | 0.0 | |

| 19 | 0.0 | |

| 20 | 0.0 | |

| 21 | 12.2 | |

| 22 | 12.2 | |

| 23 | 0.0 | |

| 24 | 0.0 | |

| 25 | 0.0 |

Fig. 6 shows these data. The gel samples were arranged after estimated molecular mass cut out from the gel. As expected, only minor sequence coverage was found in the periplasmatic fraction, due to the lipid anchor located at the carboxy-terminus. This hydrophobic region inhibits the transport of the protein to the periplasm, mediated by the amino-terminal TAT-sequence. Little fluorescence was also found in the lysis fraction, verifying our assumtion, that the protein integrates or strongly binds to the cell membrane. Using urea to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein from the cell membrane resulted only in a slightly higher sequence coverage. However, washing the pellet with 2 % Triton X-100 (v/v), 2 % SDS (w/v), previously treated with urea, resulted in a higher sequence coverage and can therefore be expected as more applicable to desintegrate the S-layer fusion protein. Sequence coverage in the supernatant of the cultivation medium can be explained with the late phase of cultivation where some cells are lysed.

To obtain more specific informations about the location of the S-layer fusion protein, after comparison with same treated fraction of E. coli KRX all gel bands in a defined size area were cut out of the gel and analysed with MALDI-TOF. Results are shown in fig. 7.

Sequence coverage was only found in the wash and the lysis fraction, again indicating that the S-layer protein is integrating in the cell membrane. Thus transport to the periplasm mediated through the amino-terminal TAT-sequence cannot take place or after transport to the periplasm binds to the inner cell membrane.

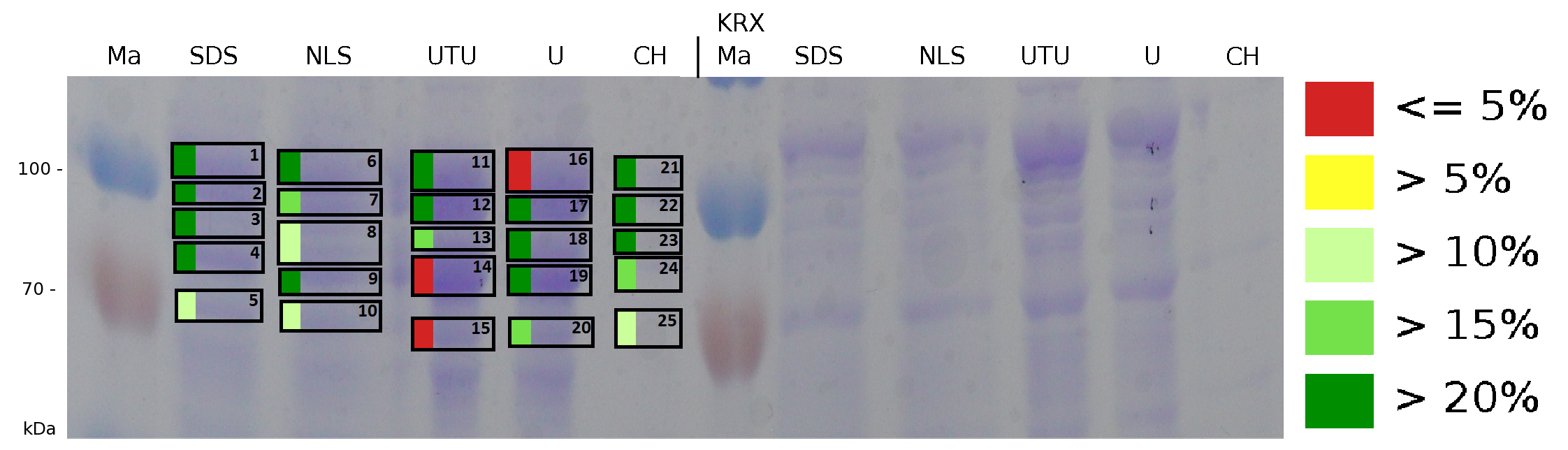

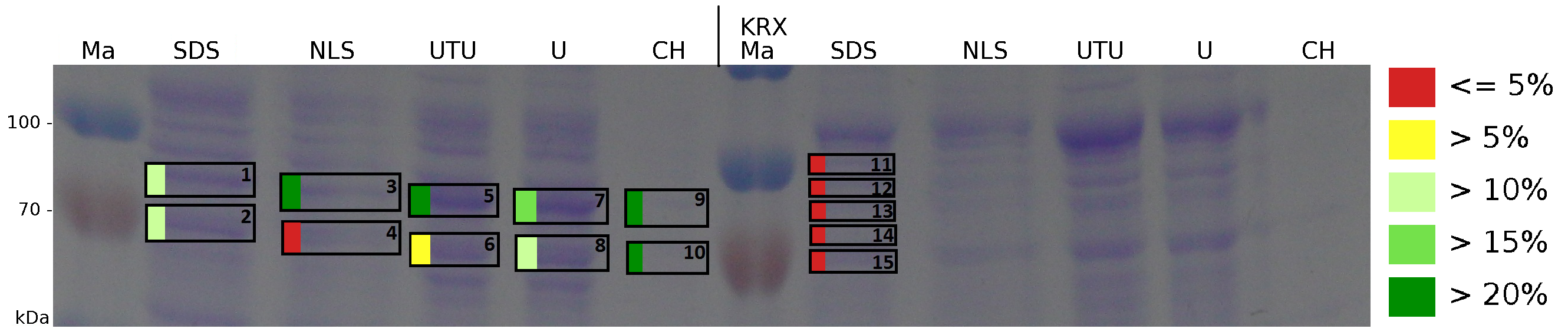

The influence of other detergents to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein was tested after disrupting the cells with a ribolyser. The cell pellet was incubated in 10 % (v/v) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), in 7 M urea and 3 M thiourea (UTU), in 10 M urea (U) in 10 % (v/v) n-lauroyl sarcosine (NLS) and in 2 % CHAPS (C). Samples of the incubations with these detergents were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE prior to measurement with MALDI TOF.

The result of the MALDI-TOF measurement clearly demonstrates that all used detergents are applicable to disintegrate the S-layer fusion proteins from the bacterial cell membrane of E. coli. Fluorescence measurement of fractions, treated with the detergents, show significantly different values, indicating that some of the detergents (e.g. 3 M thiourea, 7 M urea) have a strong effect on protein folding.

CspB without TAT-sequence and with lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

For characterization the modiefied CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525123 (K525123)] gen was fused with a monomeric RFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] using Gibson assembly.

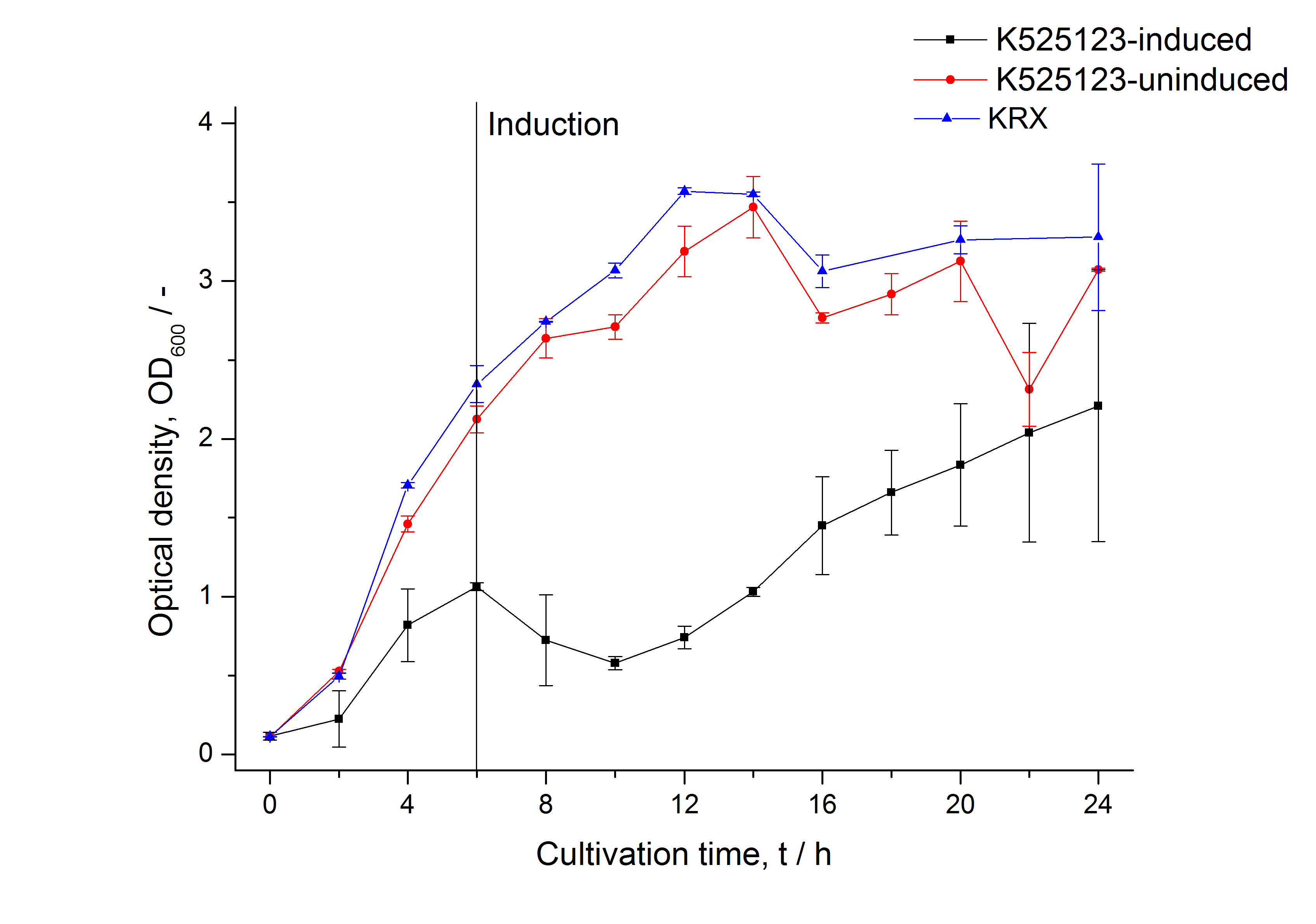

The fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the autoinduction protocol.

Identification and localisation

After a cultivation time of 18 h the mRFP|CspB fusion protein was localized in E. coli KRX. Therefor a part of the produced biomass was mechanically disrupted and the resulting lysate was washed with ddH2O. The periplasm was detached by using an osmotic shock.

The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the polyacrylamide gel after a SDS-PAGE of the lysate. This indicated that the fusion protein integrates into the cell membrane with its lipid anchor. For testing this assumption the washed lysate was treated with ionic, nonionic and zwitterionic detergents to release the mRFP|CspB out of the membranes.

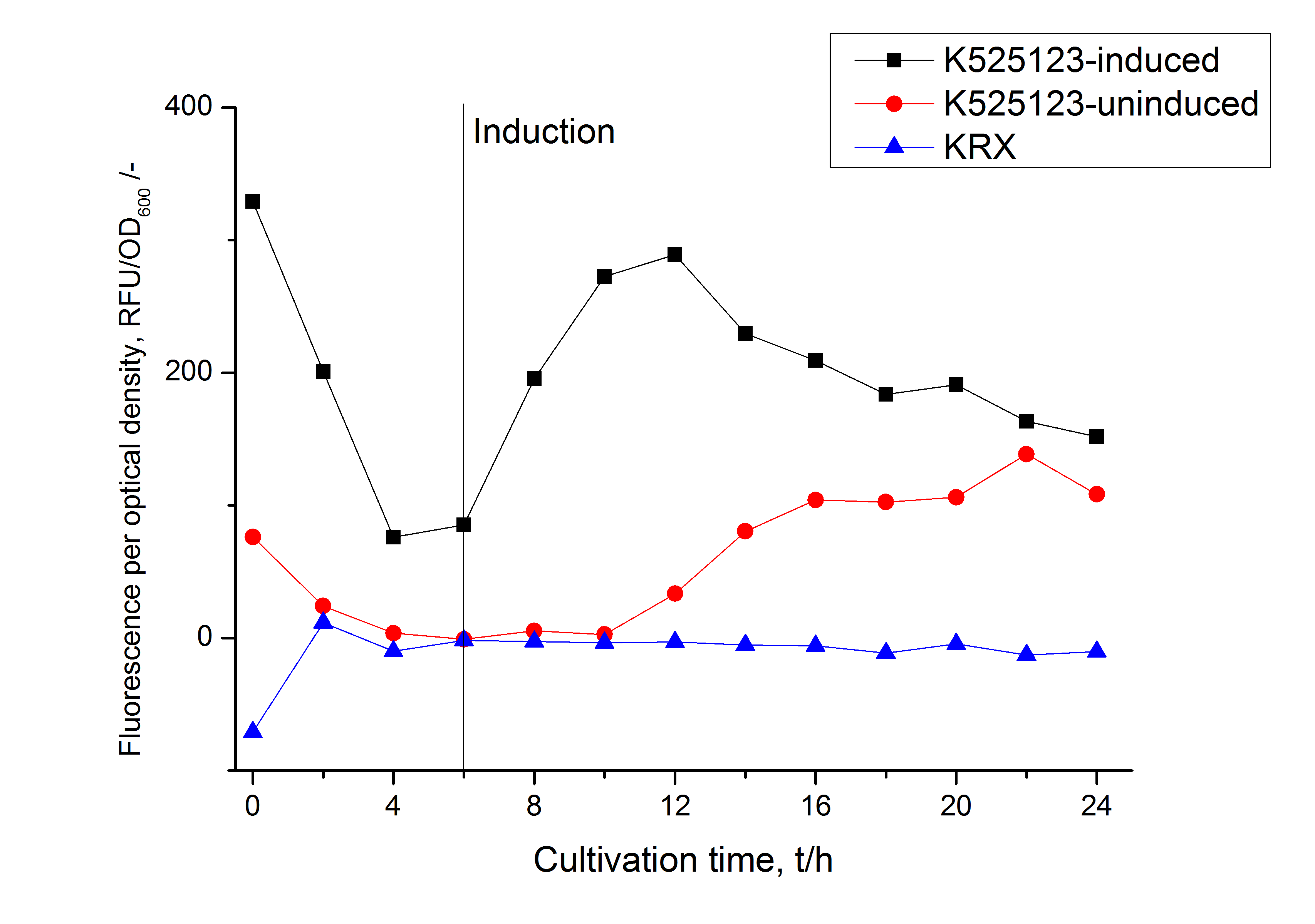

The existance of flourescence in the detergent fractions and the not existent fluorescence in the wash fraction confirms the hypothesis of an insertion into the cell membrane (fig. 11). An insertion of these S-layer proteins might stabilize the membrane structure and increase the stability of cells against mechanical and chemical treatment. A stabilization of E. coli expressing S-layer proteins was described by [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20829284 Lederer et al., (2010)].

Another important fact is that there is actually mRFP fluorescence measurable in such high concentrated detergent solutions. The S-layer seems to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP. The MALDI-TOF analysis of the relevant size range in the polyacrylamid gel approved the existance of the intact fusion protein in all detergent fractions (fig 12).

In comparison with the mRFP fusion protein of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525121 K525121], which has a TAT-sequence, a minor relative fluorescence in all cultivation and detergent fractions was detected (fig. 11). Together with the decreasing RFU/OD600 after 12 h of cultivation (fig. 10) indicates that the TAT-sequence results in a postive effect on the protein stability.

MALDI-TOF analysis was used to identify the location of the fusion protein in different fractions. Fractions of medium supernatant after cultivation (M), periplasmatic isolation (PP), cell lysis (L) and the following wash with ddH2O, samples were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE. After comparison with same treated fraction of E. coli KRX all gel bands in a defined size area were cutted out of the gel and analysed with MALDI-TOF. Results are shown in fig. 12.

Results show that the fusion protein of mRFP[http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)]/CspB without TAT-sequence and with lipid anchor has only been identified in the lysis fraction. However, in conclusion with absent TAT-sequence, the protein has not been identified in the periplasm and the culture supernatant, respectively.

The influence of other detergents to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein was tested after disrupting the cells with a ribolyser. The cell pellet was incubated in 10 % (v/v) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), in 7 M urea and 3 M thiourea (UTU), in 10 M urea (U) in 10 % (v/v) N-lauroyl sarcosine (NLS) and in 2 % CHAPS (C). Samples of the incubations with these detergents were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE prior to measurement with MALDI-TOF (fig. 13).

The results of the MALDI-TOF measurement clearly demonstrate that all used detergents are applicable to disintegrate the S-layer fusion proteins from the bacterial cell membrane of E. coli. Fluorescence measurement of fractions treated with the detergents, show significantly different values, indicating that some of the detergents (e.g. 3 M thiourea, 7 M urea) have a strong effect on protein folding. The samples taken from gel lanes of E. coli KRX show no sequence coverage, therefore not similar proteins are naturally induced in E. coli.

"

"