Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Nutshell

From 2011.igem.org

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

<p><b><a href=Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/NAD>Results</a></b>: We were able to utilize NAD<sup>+</sup>-dependent DNA ligase from <i>E. coli</i> (LigA) for a highly sensitive and selective molecular beacon based bioassay detecting NAD<sup>+</sup> in nano molarity scale (limit of detection: 2 nM). The deadenylated form of LigA could ligate nicked DNA (a split target hybridized to a molecular beacon) resulting in an increase of fluorescence intensity. In relation to this, the initial velocity displayed a linear dependence on the employed NAD<sup>+</sup> concentrations as long as these remained the limiting factor for DNA ligation. Additionally, the NAD+ bioassay has been successfully coupled to the NADH-dependent conversion of pyruvate to L-lactate by lactic acid dehydrogenase. </p> | <p><b><a href=Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/NAD>Results</a></b>: We were able to utilize NAD<sup>+</sup>-dependent DNA ligase from <i>E. coli</i> (LigA) for a highly sensitive and selective molecular beacon based bioassay detecting NAD<sup>+</sup> in nano molarity scale (limit of detection: 2 nM). The deadenylated form of LigA could ligate nicked DNA (a split target hybridized to a molecular beacon) resulting in an increase of fluorescence intensity. In relation to this, the initial velocity displayed a linear dependence on the employed NAD<sup>+</sup> concentrations as long as these remained the limiting factor for DNA ligation. Additionally, the NAD+ bioassay has been successfully coupled to the NADH-dependent conversion of pyruvate to L-lactate by lactic acid dehydrogenase. </p> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | [[Image:Bielefeld-Germany-2011_NAD+_bioassay_1.png| | + | [[Image:Bielefeld-Germany-2011_NAD+_bioassay_1.png|475px|thumb|left| '''NAD<sup>+</sup> can be detected utilizing the NAD<sup>+</sup>-dependence of LigA for a molecular beacon based bioassay.''']] |

| - | [[Image:Bielefeld-Germany-2011_NAD+_bioassay_imaging.png| | + | [[Image:Bielefeld-Germany-2011_NAD+_bioassay_imaging.png|407px|thumb|right| '''Visualization of NAD<sup>+</sup> presence with the help of the NAD<sup>+</sup> bioassay.]] |

<html> | <html> | ||

<p></p> | <p></p> | ||

Revision as of 23:31, 28 October 2011

The project

The development of sensitive and selective biosensors is an important research field in synthetic biology. Unfortunately, cellular biosensors often show negative side effects that complicate any practical application. Common problems are the limited applicability outside of a gene laboratory due to the use of genetically engineered cells, the low durability because of the utilization of living cells and the appearance of undesired signals induced by endogenous metabolic pathways.

To solve these problems, the iGEM-Team Bielefeld 2011 aims at developing a cell-free bisphenol A (BPA) biosensor based on a coupled enzyme reaction fused to S-layer proteins for everyday use. Bisphenol A is a harmful substance which is used in the production of polycarbonate. To detect BPA, it is degraded by a fusion protein under formation of NAD+ which is detected by an NAD+-dependent enzymatic reaction with a molecular beacon. Both enzymes are fused to S-layer proteins which build up well-defined nanosurfaces and are attached to the surface of beads. By providing these nanobiotechnological building blocks the system is expandable to other applications.

Subprojects

Our project is composed of three subprojects which are joined together in the project overview image below.

S-layer

S-layers (crystalline bacterial surface layer) are crystal-like layers consisting of multiple protein monomers and can be found in various (archae-)bacteria. Especially their ability for self-assembly into distinct geometries is of scientific interest. At phase boundaries, in solutions and on a variety of surfaces they form different lattice structures. By modifying the characteristics of the S-layer through combination with functional groups and protein domains it is possible to realize various practical applications. In particular for the production of cell-free biosensors, functional fusion proteins are of great importance. Enzymes fused to immobilized S-layers exhibited a significantly longer durability and were more stable against physical and chemical treatment.

We aim to assemble, produce and immobilize S-layer fusion proteins for the detection of BPA by a coupled enzymatic reaction. The provision of various S-layers with different geometries offers the possibility for the scientific community to create functional nanobiotechnological surfaces with simple and standardized methods. More information on the background can be found here.

Results: Four different S-layer BioBricks with different lattice structures were created and sent to the Partsregistry. The performance of these genes when expressed in E. coli was characterized and purification strategies for the expressed proteins were developed. Two purified fluorescent S-layer fusion proteins from different organisms were immobilized on beads, leading to a highly significant fluorescence enhancement of these beads (p < 10-14). Furthermore, regarding the other two S-layers (CspB from Corynebacterium glutamicum and Corynebacterium halotolerans), we discovered that while expression with a lipid anchor resulted in an integration into the cell membrane, the expression with a TAT-sequence resulted in a secretion into the medium. We also detected that those S-layers seem to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP. Furthermore, we expressed and purified a fluorescent CspB fusion protein from C. halotolerans which had not been expressed in E. coli before.

Bisphenol A

The organic compound bisphenol A is a key monomer in the production of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins. BPA monomers can leak in small doses from BPA-based plastics into aqueous solutions. This leads to a daily exposure to BPA. As BPA is an endocrine disruptor that mimics the natural hormone estrogen, the exposure may induce negative health effects.

In 2005 a soil bacterium was isolated which is able to degrade the environmental poison bisphenol A with a unique rate and efficiency compared to other BPA degrading organisms. Three genes which are responsible for the first step of this effective BPA degradation by were identified: a cytochrome P450 (bisdB), a ferredoxin (bisdA) and a ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR). More information on the background can be found here.

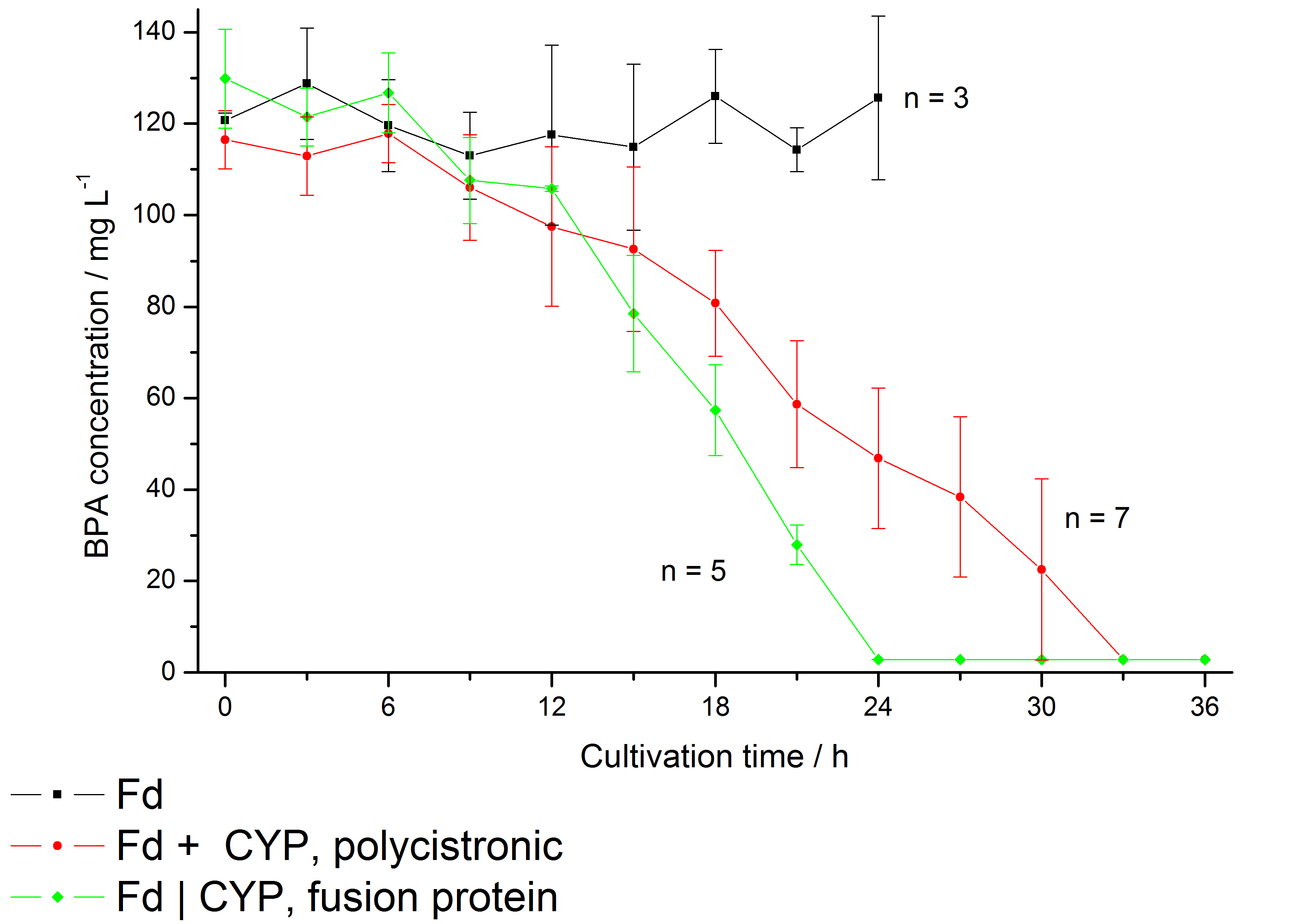

Results: We enabled E. coli to degrade BPA in vivo and improved the specific BPA degradation rate by creating a Fdbisd:CYPbisd fusion protein (BisdA | BisdB), changing the cytochrome P450 electron transport system from a putida-like bacterial class I type to a class V type.

NAD+ detection

Our selected NAD+ detection method utilizes a molecular beacon based approach. The ends of a single-stranded DNA molecule are labeled with a fluorophore as well as with an appropriate quencher. Due to a formed stem-loop both are in such a close proximity to each other that no fluorescence signal is detected. Using two complementary targets hybridizing side-by-side with the hairpin enables NAD+-dependent DNA ligation by E.coli DNA ligase. Only after closing the gap between both hybridized targets the stem opens and the secondary structure gets broken down to a linearized probe-target hybrid. The immediate consequence is a disruption of the close proximity of the fluorophore and the quencher, so that an excitation with light is converted into a visible fluorescence signal. Therefore, NAD+ concentration directly correlates with the emerging fluorescence signal. More information on the background can be found here.

Results: We were able to utilize NAD+-dependent DNA ligase from E. coli (LigA) for a highly sensitive and selective molecular beacon based bioassay detecting NAD+ in nano molarity scale (limit of detection: 2 nM). The deadenylated form of LigA could ligate nicked DNA (a split target hybridized to a molecular beacon) resulting in an increase of fluorescence intensity. In relation to this, the initial velocity displayed a linear dependence on the employed NAD+ concentrations as long as these remained the limiting factor for DNA ligation. Additionally, the NAD+ bioassay has been successfully coupled to the NADH-dependent conversion of pyruvate to L-lactate by lactic acid dehydrogenase.

Human Practice

While developing our project idea, we were already integrating biosafety aspects in our blueprint and came up with the idea of cell-free biosensors. Besides higher durability and more specific signals, cell-free biosensors have the significant advantage that for the application and production all GMOs stay in the controlled environment of the lab. All cells are grown under controlled conditions and only qualified personnel have access to them. This minimizes the risk of releasing GMOs into the environment and therefore the possibility of horizontal gene transfer.

We got an expert view on cell-free biosensors concerning technology assessment, biosafety and the embedment in the current discussions about synthetic biology by Dr. Arnold Sauter from the Office of Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag (TAB).

The goals of our outreach are to rise public awareness, start public discussions and participate in the discussion about iGEM. Additonally, we want to promote the open source idea behind iGEM, arouse interest and hopefully prevented fear when facing the principles of synthetic biology. Therefore, we organized and participated in various events. Check out our Human Practices section for more information.

Furthermore we provided a guide to do it yourself nanobiotechnology for fellow scientists, with detailed step by step instructions.

Achievements

With the BioBricks submitted by our team, we enable a fast and selective BPA degradation in E.coli, a highly sensitive and selective NAD+ detection that provides a versatile NAD+ bioassay for future iGEM teams and the immobilization of S-layer fusion proteins, which implies the use of our S-layer proteins as nanobiotechnological building blocks.

Since our approach is cell-free, we can guarantee a high biosafety of our biosensor and were able to create a rather simple model for BPA detection.

Check out our Achievements page, if you want to know about further achievements of our team.

"

"