Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/S-Layer

From 2011.igem.org

(→Identification and localisation) |

(→Identification and localisation) |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

===Identification and localisation=== | ===Identification and localisation=== | ||

| - | After cultivation the | + | After a cultivation time of 18 h the mRFP|CspB fusion protein has to be localized in ''E. coli'' KRX. Therefore a part of the produced biomass was mechanically disrupted and the resulting lysate was washed with ddH<sub>2</sub>O. The periplasm was detached by using a osmotic shock from other parts of the cells. The existance of fluorescene in the periplasm fraction, showed in fig. 3, indicates that ''C. glutamicum'' TAT-signal sequence is at least in part functional in ''E. coli'' KRX. |

| - | The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the polyacrylamide gel after a | + | The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the polyacrylamide gel after a SDS-PAGE of the lysate and the cell debris were still red. This indicates that the fusion protein intigrates with the lipid anchor into the cell membrane. For testing this assumption the washed lysate was treated with ionic, nonionic and zwitterionic detergents to release the mRFP|CspB out of the membranes. |

| - | The | + | The existance of flourescence in the detergent fractions and the proportionally to the lysis fraction low fluorescence in the wash fraction confirm the hypothesis of an insertion into the cell membrane (fig. 3). An insertion of these S-layer proteins might stabilize the membrane structure and increase the stability of cells against mechanical and chemical treatment. A stabilization of ''E. coli'' expressing S-layer proteins was discribed by Lederer ''et al.'', (2010). |

| + | An other important fact is, that there is actually mRFP fluorescence measurable in such high concentrated detergent solutions. The S-layer seems to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP. The MALDI-TOF analysis of the relevant size range in the polyacrylamid gel approved the existance of the intact fusion protein in all detergent fractions (fig 4). | ||

| - | [[Image:Bielefeld 2011 BF1 Purification.png|700px|thumb|center| '''Figure | + | |

| + | [[Image:Bielefeld 2011 BF1 Purification.png|700px|thumb|center| '''Figure 3: Fluorescence progression of the mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)]/CspB fusion protein initiating with the cultivation fractions up to the detergent fractions of the seperate denaturations. Cultivations were carried out in autoinduction medium at 37 ˚C. The cells were mechanically disrupted and the resulting biomass was wahed with ddH<sub>2</sub>O and resuspendet in the respective detergent. The used detergent acronyms stand for: SDS = 10 % (v/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate; UTU = 7 M urea and 3 M thiourea; U = 10 M urea; NLS = 10 % (v/v) n-lauroyl sarcosine; CHAPS = 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | MALDI-TOF analysis was first used to identify the location of the fusion protein in different fractions. Fractions of medium supernatant after cultivation, periplasmatic isolation, cell lysis, denaturation in 6 M urea and the following wash with 2 % (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 % SDS (w/v) were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE and fragments of the gel were measured with MALDI-TOF. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Bielefeld2011 K525131 page maldi.png|900px|thumb|center| '''Figure 4: SDS-PAGE of CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein. Lanes are fractions of culture supernatant (M), periplasmatic isolation (PP), cell lysis (L), denaturation (D) and a wash of the pellet of the denaturation with Triton X-100 (T). Used marker is PageRuler <sup>TM</sup> Prestained Protein Ladder SM0671. Marked regions were cut out and prepared for MALDI-TOF analysis.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following table shows the sequence coverage (in %) of our measurable gel samples with the amino acid sequence of fusion protein CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | {|{{Table}} | ||

| + | !number of gel sample | ||

| + | !sequence coverage (%) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |1.9 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |2 | ||

| + | |11.5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |8.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |2.6 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |6 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |7 | ||

| + | |2.6 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |8 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |9 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |10 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |11 | ||

| + | |9.4 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |12 | ||

| + | |2.6 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |13 | ||

| + | |2.8 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |14 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |15 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |16 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |17 | ||

| + | |8.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |18 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |19 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |20 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |21 | ||

| + | |12.2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |22 | ||

| + | |12.2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |23 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |24 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |25 | ||

| + | |0.0 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fig. 5 shows these data. The gel samples were arranged after estimated molecular mass cut out from the gel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Bielefeld2011_K525131_BF1_maldi_graph.png|700px|thumb|center| '''Figure 5: MALDI TOF measurement of CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein. Samples are arranged after estimated molecular mass of the gel slice. Measurement was performed with a ultrafleXtreme<sup>TM</sup> by Bruker Daltonics using the software FlexAnalysis, Biotools and SequenceEditor.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As expected, only minor sequence coverage was found in the periplasmatic fraction, due to the lipid anchor located at the carboxy-terminus. This hydrophobic region inhibits the transport of the protein to the periplasm, mediated by the amino-terminal TAT-sequence. Little fluorescence was also found in the lysis fraction, verifying our assumtion, that the protein integrates or strongly binds to the cell membrane. Using urea to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein from the cell membrane resulted only in a slightly higher sequence coverage. However, washing the pellet with 2 % Triton X-100 (v/v), 2 % SDS (w/v), previously treated with urea, resulted in a higher sequence coverage and can therefore be expected as more applicable to desintegrate the S-layer fusion protein. Sequence coverage in the supernatant of the cultivation medium can be explained with the late phase of cultivation where some cells are lysed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To obtain more specific informations about the location of the S-layer fusion protein, after comparison with same treated fraction of ''E. coli'' KRX all gel bands in a defined size area were cut out of the gel and analysed with MALDI-TOF. Results are shown in fig. 6. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

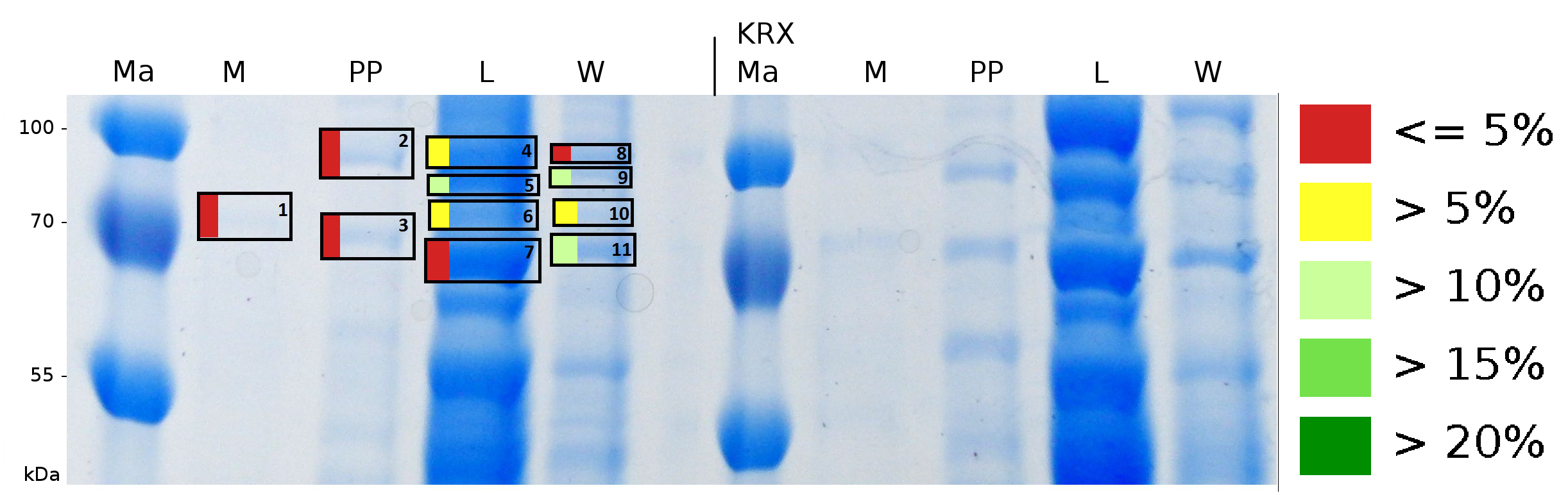

| + | [[Image:Bielefeld2011_K525131_BF1_Gel1.png|900px|thumb|right| '''Figure 6: MALDI-TOF measurement of CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] fusion protein in different fractions. Abbreviations are Ma: Marker (PageRuler <sup>TM</sup> Prestained Protein Ladder SM0671), M (medium), PP (periplasm), L (cell lysis with ribolyser), W (wash with ddH<sub>2</sub>O). In the left half of the gel fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX with induced production of fusion protein, the right half shows fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX without carrying the plasmid coding the fusion protein. Colours show the sequence coverage of the gel lane, cutted out of the gel.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sequence coverage was only found in the wash and the lysis fraction, again indicating that the S-layer protein is integrating in the cell membrane. Thus transport to the periplasm mediated through the amino-terminal TAT-sequence cannot take place or after transport to the periplasm binds to the inner cell membrane. | ||

| + | |||

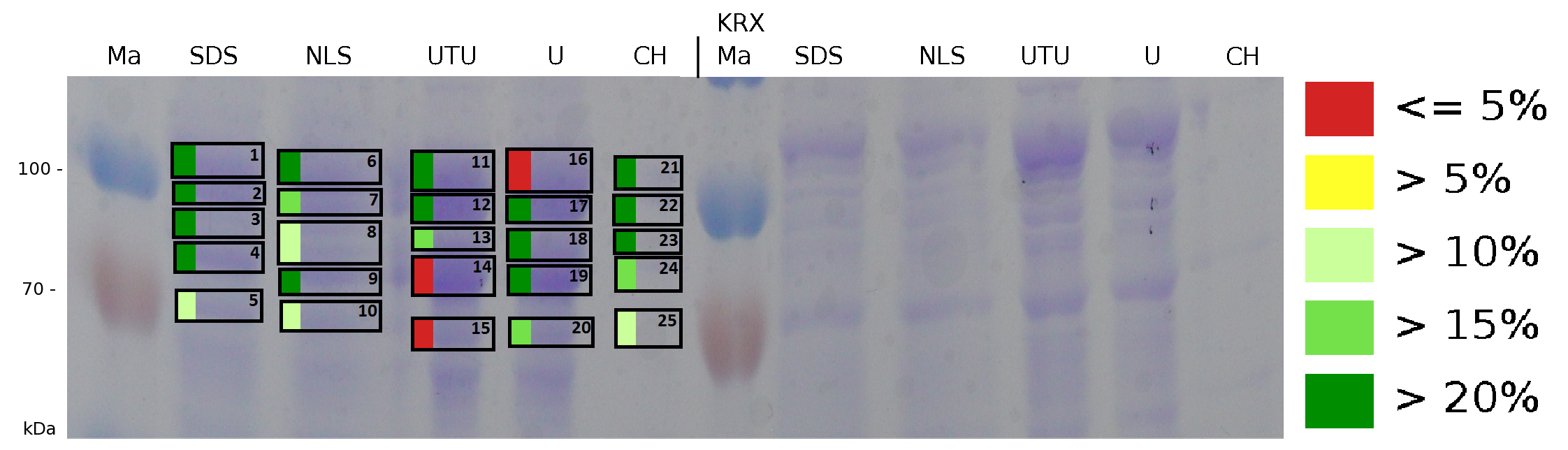

| + | The influence of other detergents to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein was tested after disrupting the cells with a ribolyser. The cell pellet was incubated in 10 % (v/v) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), in 7 M urea and 3 M thiourea (UTU), in 10 M urea (U) in 10 % (v/v) n-lauroyl sarcosine (NLS) and in 2 % CHAPS (C). Samples of the incubations with these detergents were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE prior to measurement with MALDI TOF. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Bielefeld2011 K525131 BF1 Gel2 maldi.png|900px|thumb|left| '''Figure 7: Influence of diffent detergents on the disintegration of the fusionprotein CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] from the cell membrane of ''E. coli'' KRX. Abbreviations are: SDS (Sodium dodecyl sulfate 10 % (w/v)), NLS ((10 % (w/v) m-lauroyl sarcosine), UTU (3 M thiourea, 7 M urea), U (10 M urea), CH (2% CHAPS 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate), Ma Marker (PageRuler <sup>TM</sup> Prestained Protein Ladder SM0671). On the left half of the gel fractions of the S-layer fusion protein are displayed, on the right half fractions of ''E. coli'' KRX are displayed.''']] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The result of the MALDI-TOF measurement clearly demonstrates that all used detergents are applicable to disintegrate the S-layer fusion proteins from the bacterial cell membrane of ''E. coli''. Fluorescence measurement of fractions, treated with the detergents, show significantly different values, indicating that some of the detergents (''e.g.'' 3 M thiourea, 7 M urea) have a strong effect on protein folding. | ||

==CspB without TAT-sequence and with lipid anchor== | ==CspB without TAT-sequence and with lipid anchor== | ||

Revision as of 00:59, 22 September 2011

SgsE from Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a

Purification of SgsE fusion protein

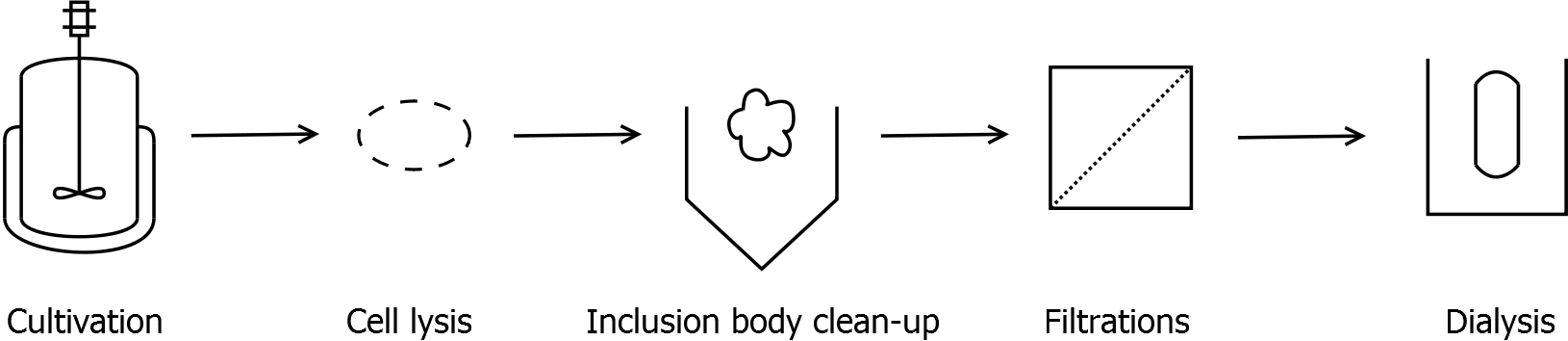

As seen in the analysis of the cultivations with expression of SgsE | mCitrine fusion proteins, these proteins form inclusion bodies in E. coli. Inclusion bodies have the advantage that they are relatively easy to clean-up and are resistant to proteases. So the first purification step is to solve and set-free the inclusion bodies. This step is followed by two filtrations (300 kDa UF and 100 kDa DF/UF) to further concentrate and purify the S-layer proteins. After the filtrations, the remaining protein solution is dialized against ddH2O for 18 h at 4 °C in the dark. The dialysis leads to a precipitation of the water-insoluble proteins. After centrifugation of the dialysate the water-soluble S-layer monomers remain in the supernatant and can be used for recrystallization experiments.

The fluorescence of the collected fractions of this purification strategy is shown in the following figure A:

A lot of protein is lost during the purification especially after centrifugation steps. The fluorescence in the urea containing fractions is lowered due to denaturation of the fluorescent protein. Some fluorescence could be regenerated by the recrystallization in HBSS. This purification strategy is very simple and can be carried out by nearly everyone in any lab being one first step to enable real do it yourself nanobiotechnology.

Final purification strategy

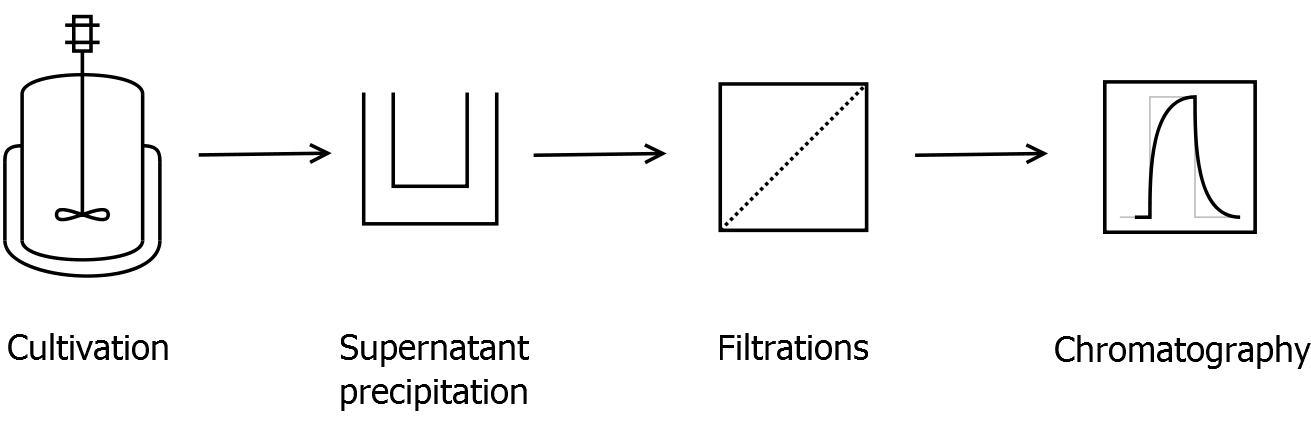

Scheme of purification strategy for SgsE (fusion) proteins:

First, SgsE is expressed in E. coli under the control of a T7 / lac promoter for separation of growth and production phase due to metabolic stress of the S-layer expression. Because the SgsE protein is forming inclusion bodies in E. coli, an inclusion body purification with urea follows the cell lysis. The S-layers are further concentrated and purified by two ultrafiltration / diafiltration steps (300 kDa and 100 kDa) and afterwards dialysed against water leading to the precipitation of water-insoluble proteins. The supernatant contains the monomeric SgsE solution.

Click for detailed information

Immobilization behaviour

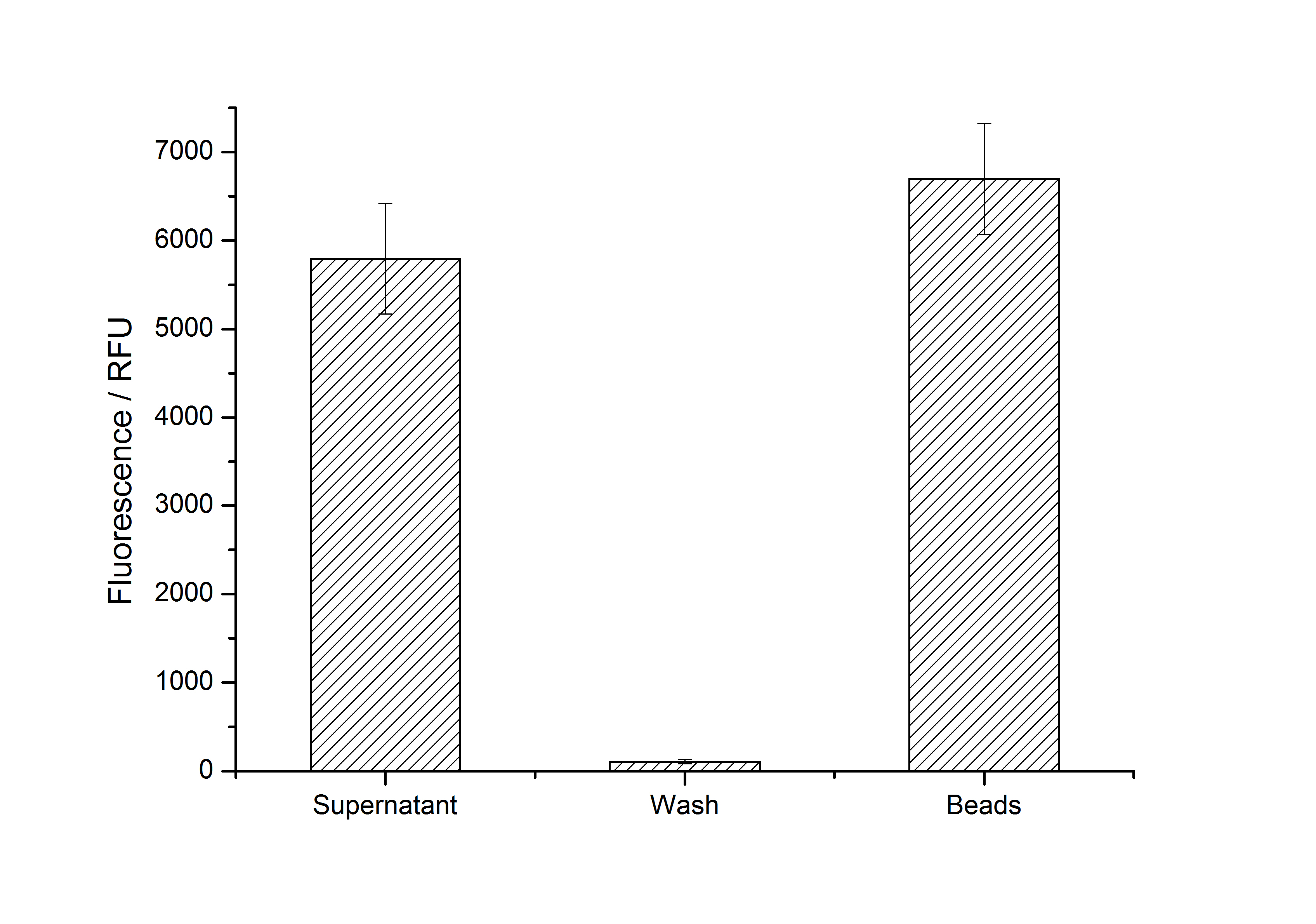

After purification, solutions of monomeric SgsE S-layer proteins can be recrystallized and immobilized on silicon dioxide beads in HBSS (Hank's buffered saline solution). After the recrystallization procedure the beads are washed with and stored in ddH2O at 4 °C in the dark. The fluorescence of the collected fractions of a recrystallization experiment with <partinfo>K525305</partinfo> are shown in fig. X. 100 mg beads were coated with 100 µg of protein. The figure shows, that not all of the protein is immobilized on the beads (supernatant fraction) but the immobilization is pretty stable (very low fluorescence in the wash). After the immobilization, the beads show a high fluorescence indicating the binding of the SgsE | mCitrine fusion protein.

Optimal bead to protein ratio for immobilization

To determine the optimal ratio of silica beads to protein for immobilization, the degree of clearance ϕC in the supernatant is calculated and plotted against the concentration of silica beads used in the accordant immobilization experiment (compare fig. A):

The data was collected in three indipendent experiments. The fluorescence of the samples was measured in the supernatant of the immobilization experiment after centrifuging the silica beads. The fluorescence of the control was measured in a sample which was treated exactly like the others but no silica beads were added. 100 µg protein was used for one immobilization experiment. The data was fitted with a sigmoidal dose-response function of the form

with the Hill coefficient p, the bottom asymptote A1, the top asymptote A2 and the switch point log(x0) (R² = 0.874).

The fit indicates that a good silica concentration for 100 µg of protein is 150 - 200 mg mL-1. This set-up leads to saturated beads with low waste of protein. So a good protein / bead ratio to work with is 5 - 7 * 10-4.

SbpA from Lysinbacillus sphaericus CCM 2177

Purification of SbpA fusion protein

As seen in the analysis of the cultivations with expression of SbpA | mCitrine fusion proteins, these proteins form inclusion bodies in E. coli. Inclusion bodies have the advantage that they are relatively easy to clean-up and are resistant to proteases. So the first purification step is to solve and set-free the inclusion bodies. This step is followed by two filtrations (300 kDa UF and 100 kDa DF/UF) to further concentrate and purify the S-layer proteins. After the filtrations, the remaining protein solution is dialized against ddH2 for 18 h at 4 °C in the dark. The dialysis leads to a precipitation of the water-insoluble proteins. After centrifugation of the dialysate the water-soluble S-layer monomers remain in the supernatant and can be used for recrystallization experiments.

The fluorescence of some collected, important fractions of this purification strategy is shown in the following figure A:

A lot of protein is lost during the purification especially after centrifugation steps (compared to filtrations). The fluorescence in the urea containing fractions is lowered due to denaturation of the fluorescent protein. This purification strategy is very simple and can be carried out by nearly everyone in any lab being one first step to enable real do it yourself nanobiotechnology.

Final purification strategy

Scheme of purification strategy for SbpA (fusion) proteins:

First, SbpA is expressed in E. coli under the control of a T7 / lac promoter for separation of growth and production phase due to metabolic stress of the S-layer expression. Because the SbpA protein is forming inclusion bodies in E. coli, an inclusion body purification with urea follows the cell lysis. The S-layers are further concentrated and purified by two ultrafiltration / diafiltration steps (300 kDa and 100 kDa) and afterwards dialysed against water leading to the precipitation of water-insoluble proteins. The supernatant contains the monomeric SbpA solution.

Click for detailed information

Immobilization behaviour

After purification, solutions of monomeric SbpA S-layer proteins can be recrystallized and immobilized on silicon dioxide beads in recrystallization buffer (0.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9, 10 mM CaCl2). After the recrystallization procedure the beads are washed with and stored in ddH2O at 4 °C in the dark. The fluorescence of the collected fractions of a recrystallization experiment with <partinfo>K525405</partinfo> are shown in fig. X. 100 mg beads were coated with 100 µg of protein. The figure shows, that not all of the protein is immobilized on the beads (supernatant fraction) but the immobilization is pretty stable (very low fluorescence in the wash). After the immobilization, the beads show a high fluorescence indicating the binding of the SbpA | mCitrine fusion protein.

Optimal bead to protein ratio for immobilization

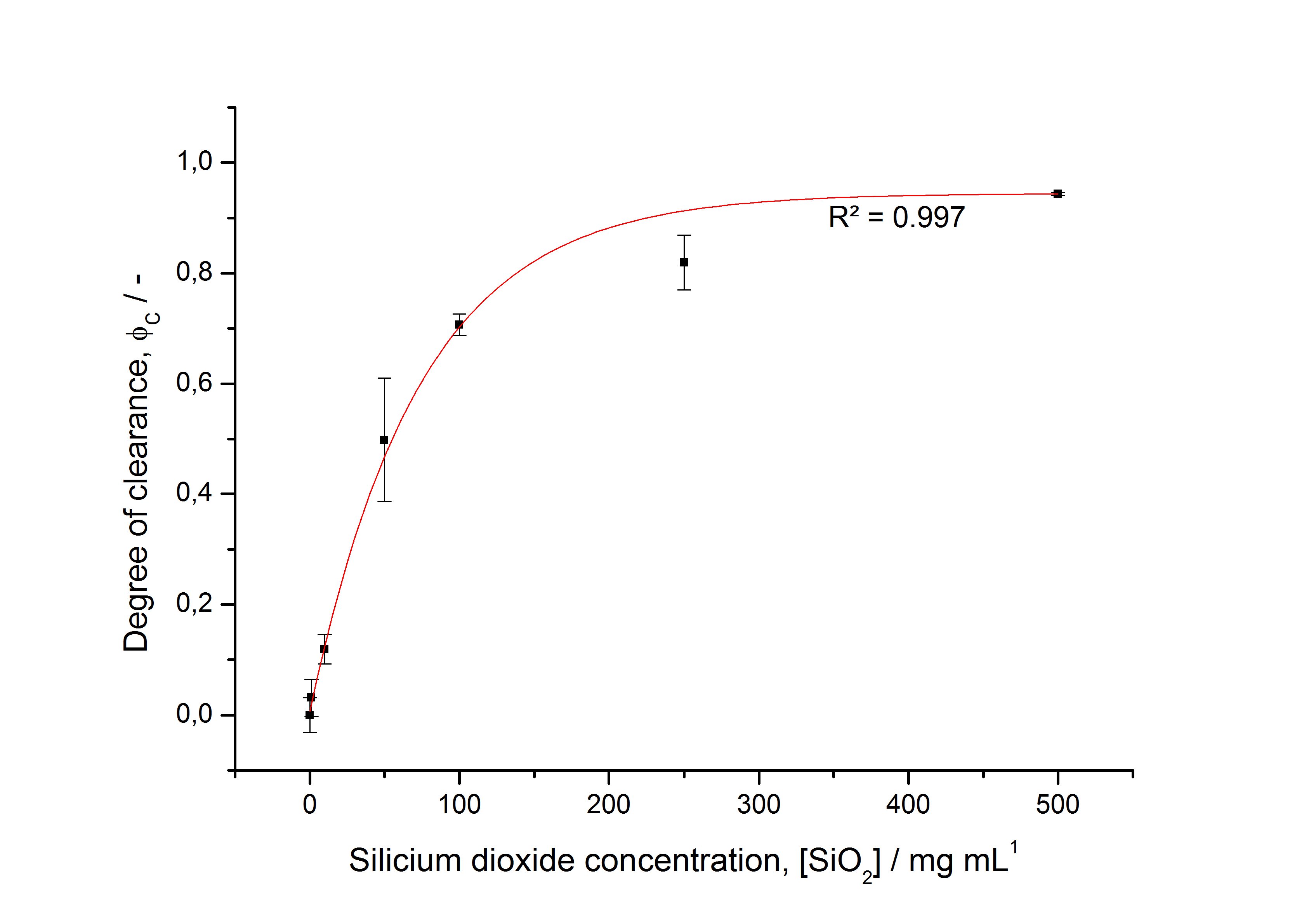

To determine the optimal ratio of silica beads to protein for immobilization, the degree of clearance ϕC in the supernatant is calculated and plotted against the concentration of silica beads used in the accordant immobilization experiment (compare fig. A):

The data was collected in three indipendent experiments. The fluorescence of the samples was measured in the supernatant of the immobilization experiment after centrifuging the silica beads. The fluorescence of the control was measured in a sample which was treated exactly like the others but no silica beads were added. 100 µg protein was used for one immobilization experiment. The data was fitted with a sigmoidal dose-response function of the form

with the Hill coefficient p, the bottom asymptote A1, the top asymptote A2 and the switch point log(x0) (R² = 0.997).

The fit indicates that a good silica concentration for 100 µg of protein is 200 - 250 mg mL-1. This set-up leads to saturated beads with low waste of protein. So a good protein / bead ratio to work with is 7 - 9 * 10-4.

CspB from Brevibacterium flavum

CspB with TAT-sequence and lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

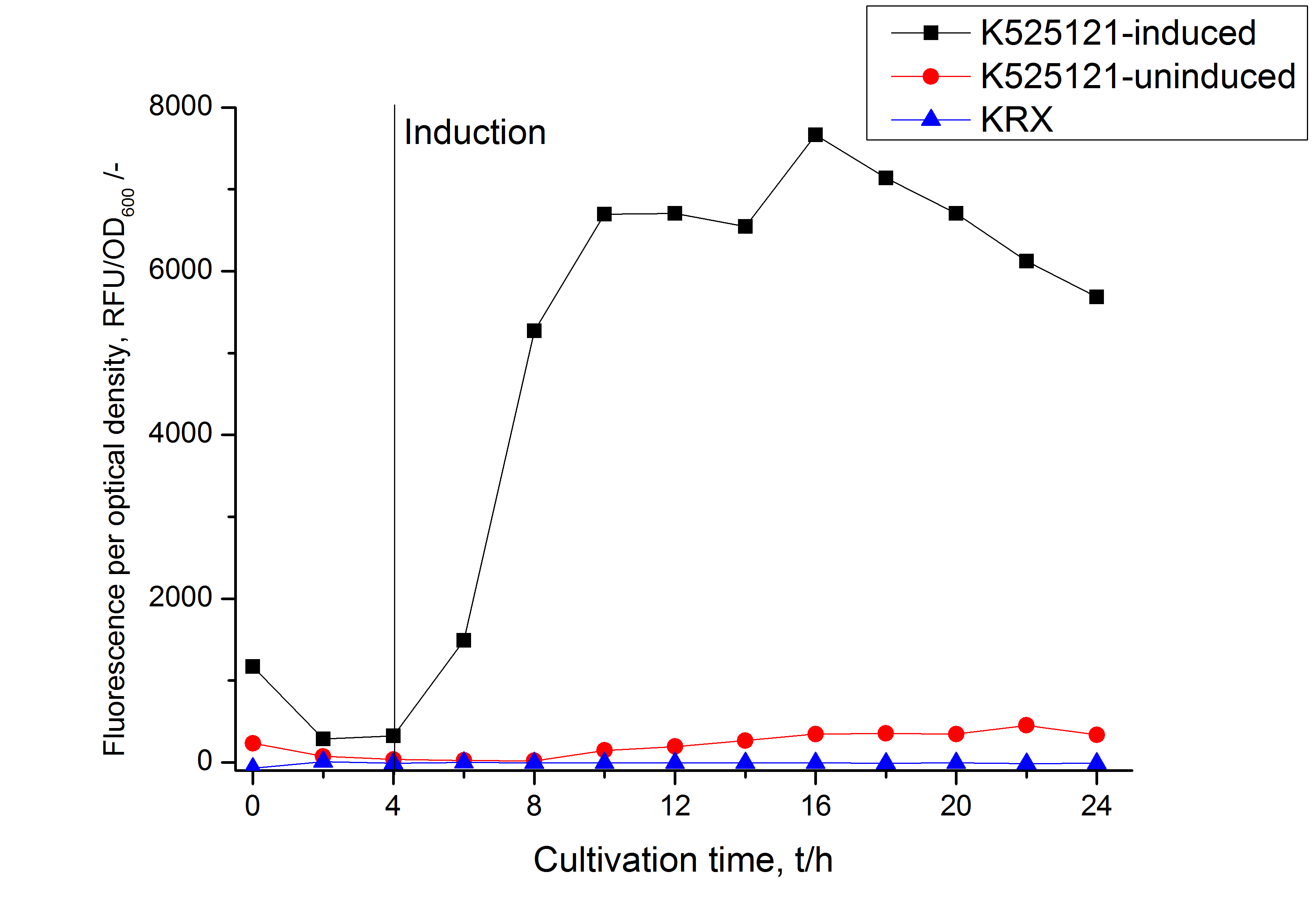

For characterization CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525121 (K525121)] gen was fused with a monomeric RFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] using Gibson assembly.

The CspB|mRFP fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the autoinduction protocol.

Identification and localisation

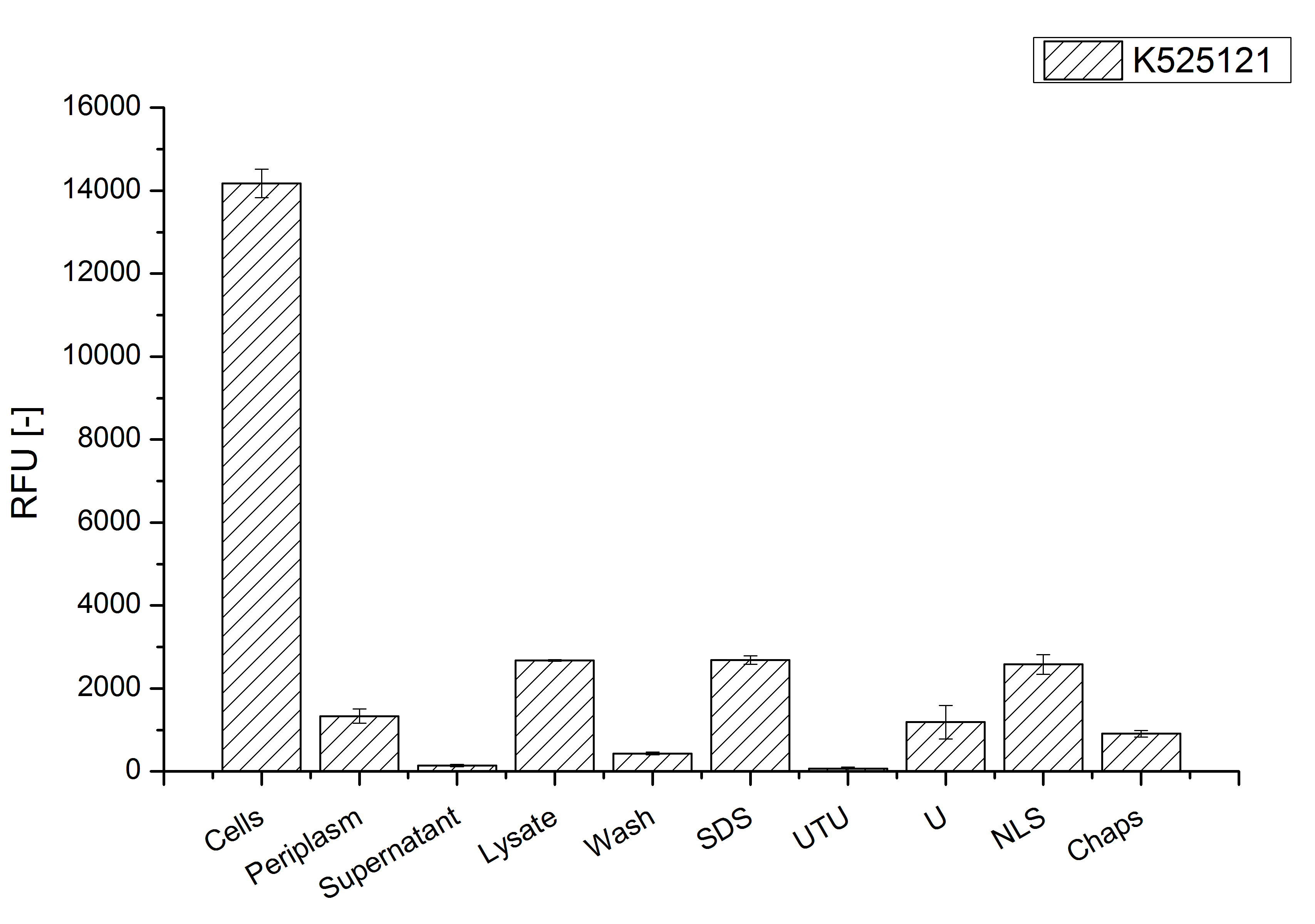

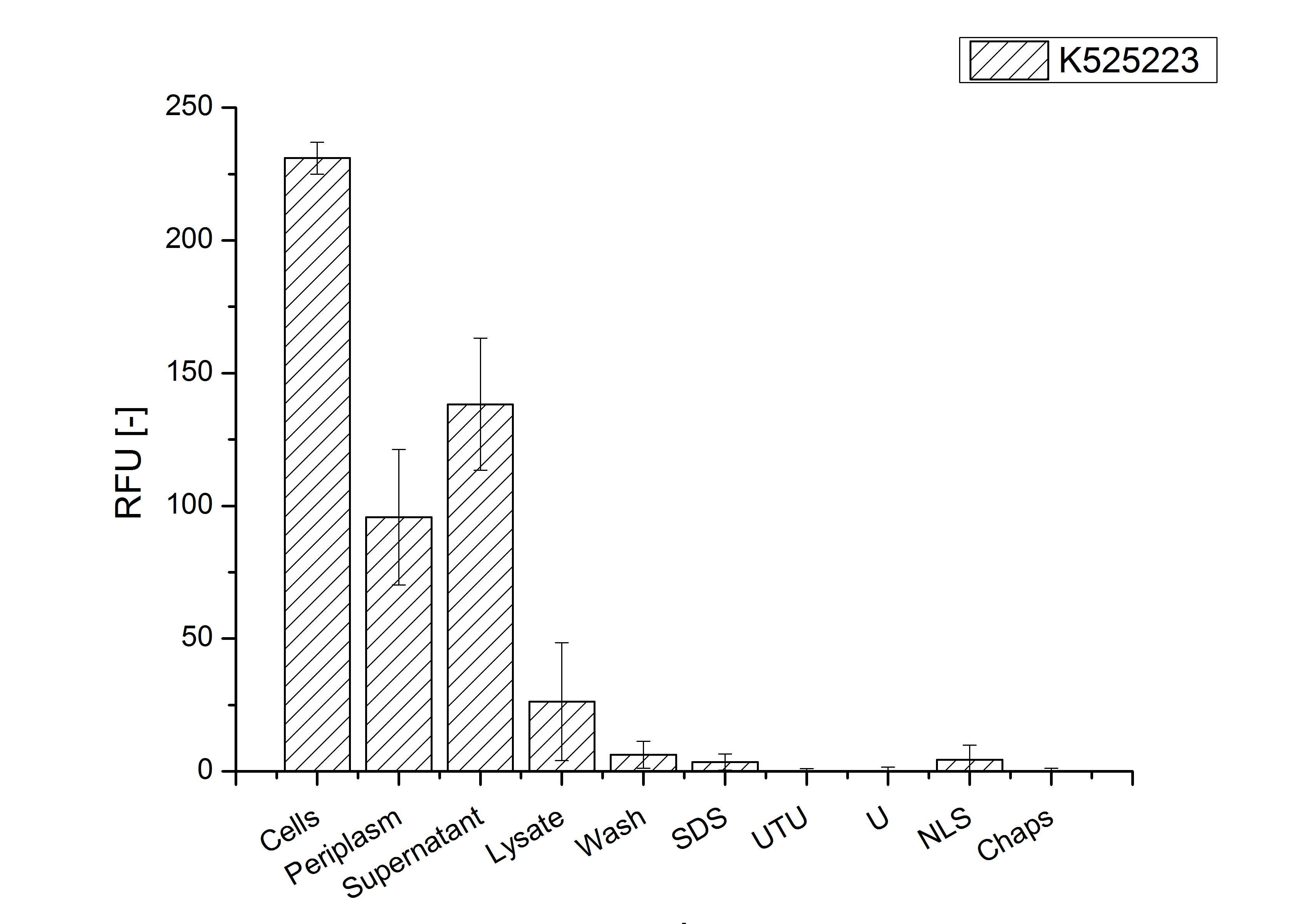

After a cultivation time of 18 h the mRFP|CspB fusion protein has to be localized in E. coli KRX. Therefore a part of the produced biomass was mechanically disrupted and the resulting lysate was washed with ddH2O. The periplasm was detached by using a osmotic shock from other parts of the cells. The existance of fluorescene in the periplasm fraction, showed in fig. 3, indicates that C. glutamicum TAT-signal sequence is at least in part functional in E. coli KRX.

The S-layer fusion protein could not be found in the polyacrylamide gel after a SDS-PAGE of the lysate and the cell debris were still red. This indicates that the fusion protein intigrates with the lipid anchor into the cell membrane. For testing this assumption the washed lysate was treated with ionic, nonionic and zwitterionic detergents to release the mRFP|CspB out of the membranes.

The existance of flourescence in the detergent fractions and the proportionally to the lysis fraction low fluorescence in the wash fraction confirm the hypothesis of an insertion into the cell membrane (fig. 3). An insertion of these S-layer proteins might stabilize the membrane structure and increase the stability of cells against mechanical and chemical treatment. A stabilization of E. coli expressing S-layer proteins was discribed by Lederer et al., (2010).

An other important fact is, that there is actually mRFP fluorescence measurable in such high concentrated detergent solutions. The S-layer seems to stabilize the biologically active conformation of mRFP. The MALDI-TOF analysis of the relevant size range in the polyacrylamid gel approved the existance of the intact fusion protein in all detergent fractions (fig 4).

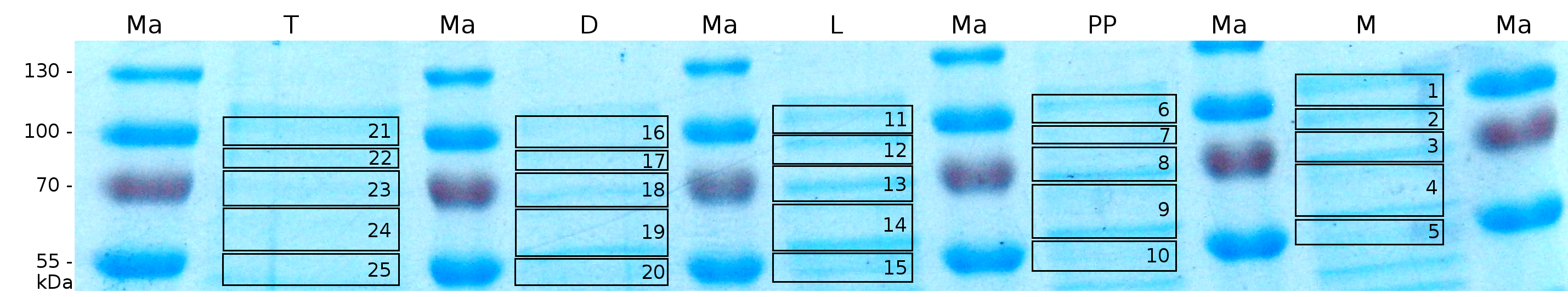

MALDI-TOF analysis was first used to identify the location of the fusion protein in different fractions. Fractions of medium supernatant after cultivation, periplasmatic isolation, cell lysis, denaturation in 6 M urea and the following wash with 2 % (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 % SDS (w/v) were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE and fragments of the gel were measured with MALDI-TOF.

The following table shows the sequence coverage (in %) of our measurable gel samples with the amino acid sequence of fusion protein CspB/mRFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)].

| number of gel sample | sequence coverage (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.9 |

| 2 | 11.5 |

| 3 | 8.0 |

| 4 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 2.6 |

| 8 | 0.0 |

| 9 | 0.0 |

| 10 | 0.0 |

| 11 | 9.4 |

| 12 | 2.6 |

| 13 | 2.8 |

| 14 | 0.0 |

| 15 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 0.0 |

| 17 | 8.0 |

| 18 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.0 |

| 21 | 12.2 |

| 22 | 12.2 |

| 23 | 0.0 |

| 24 | 0.0 |

| 25 | 0.0 |

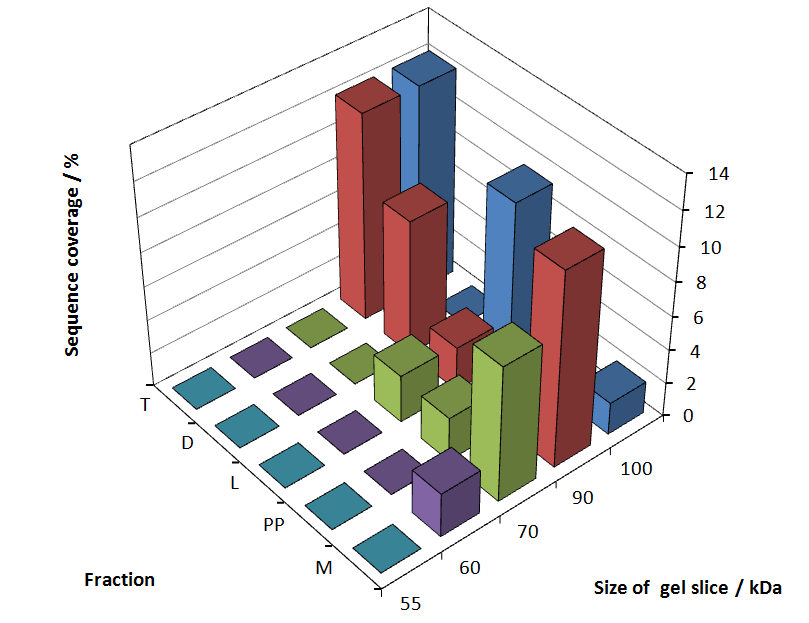

Fig. 5 shows these data. The gel samples were arranged after estimated molecular mass cut out from the gel.

As expected, only minor sequence coverage was found in the periplasmatic fraction, due to the lipid anchor located at the carboxy-terminus. This hydrophobic region inhibits the transport of the protein to the periplasm, mediated by the amino-terminal TAT-sequence. Little fluorescence was also found in the lysis fraction, verifying our assumtion, that the protein integrates or strongly binds to the cell membrane. Using urea to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein from the cell membrane resulted only in a slightly higher sequence coverage. However, washing the pellet with 2 % Triton X-100 (v/v), 2 % SDS (w/v), previously treated with urea, resulted in a higher sequence coverage and can therefore be expected as more applicable to desintegrate the S-layer fusion protein. Sequence coverage in the supernatant of the cultivation medium can be explained with the late phase of cultivation where some cells are lysed.

To obtain more specific informations about the location of the S-layer fusion protein, after comparison with same treated fraction of E. coli KRX all gel bands in a defined size area were cut out of the gel and analysed with MALDI-TOF. Results are shown in fig. 6.

Sequence coverage was only found in the wash and the lysis fraction, again indicating that the S-layer protein is integrating in the cell membrane. Thus transport to the periplasm mediated through the amino-terminal TAT-sequence cannot take place or after transport to the periplasm binds to the inner cell membrane.

The influence of other detergents to disintegrate the S-layer fusion protein was tested after disrupting the cells with a ribolyser. The cell pellet was incubated in 10 % (v/v) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), in 7 M urea and 3 M thiourea (UTU), in 10 M urea (U) in 10 % (v/v) n-lauroyl sarcosine (NLS) and in 2 % CHAPS (C). Samples of the incubations with these detergents were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE prior to measurement with MALDI TOF.

The result of the MALDI-TOF measurement clearly demonstrates that all used detergents are applicable to disintegrate the S-layer fusion proteins from the bacterial cell membrane of E. coli. Fluorescence measurement of fractions, treated with the detergents, show significantly different values, indicating that some of the detergents (e.g. 3 M thiourea, 7 M urea) have a strong effect on protein folding.

CspB without TAT-sequence and with lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

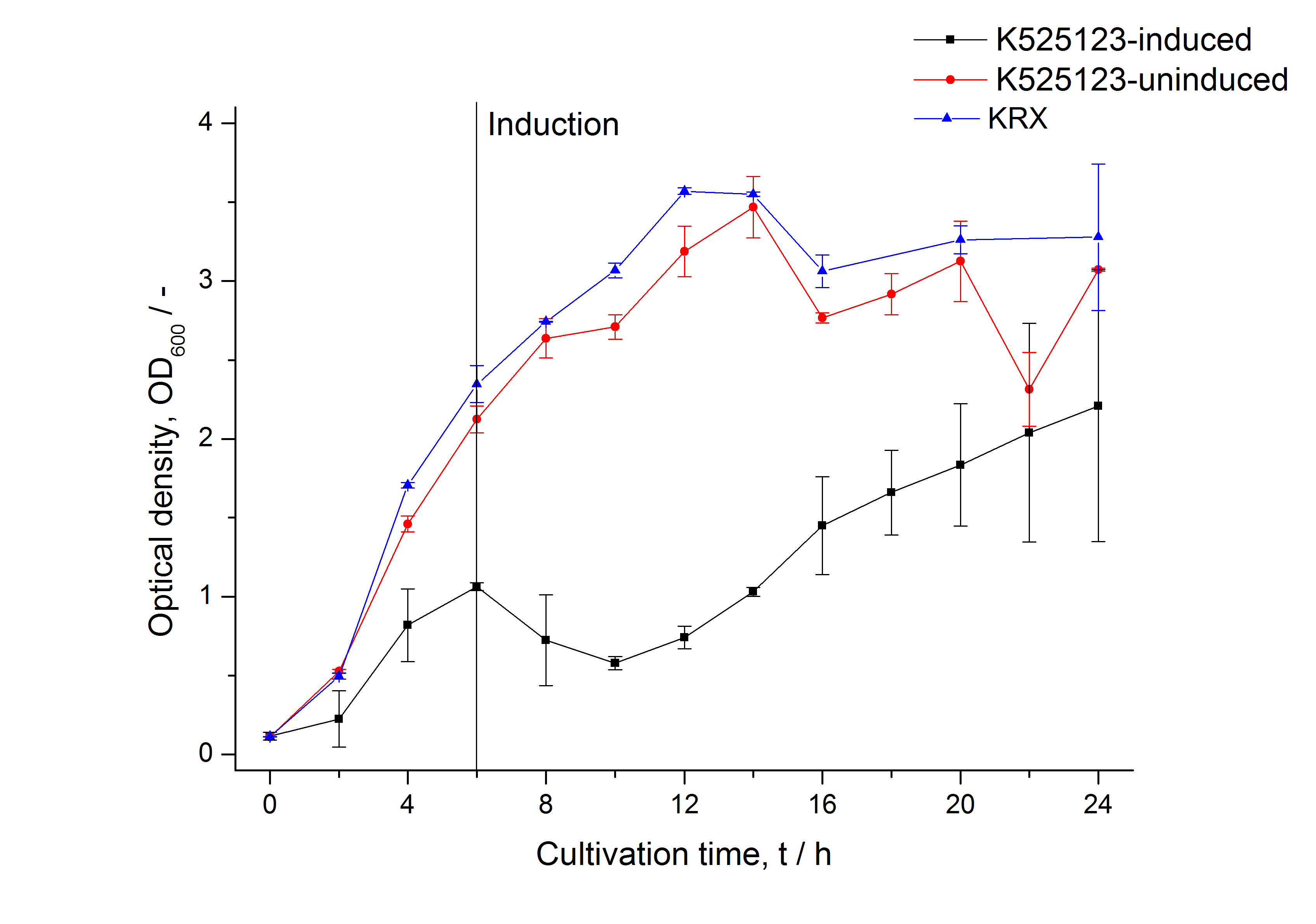

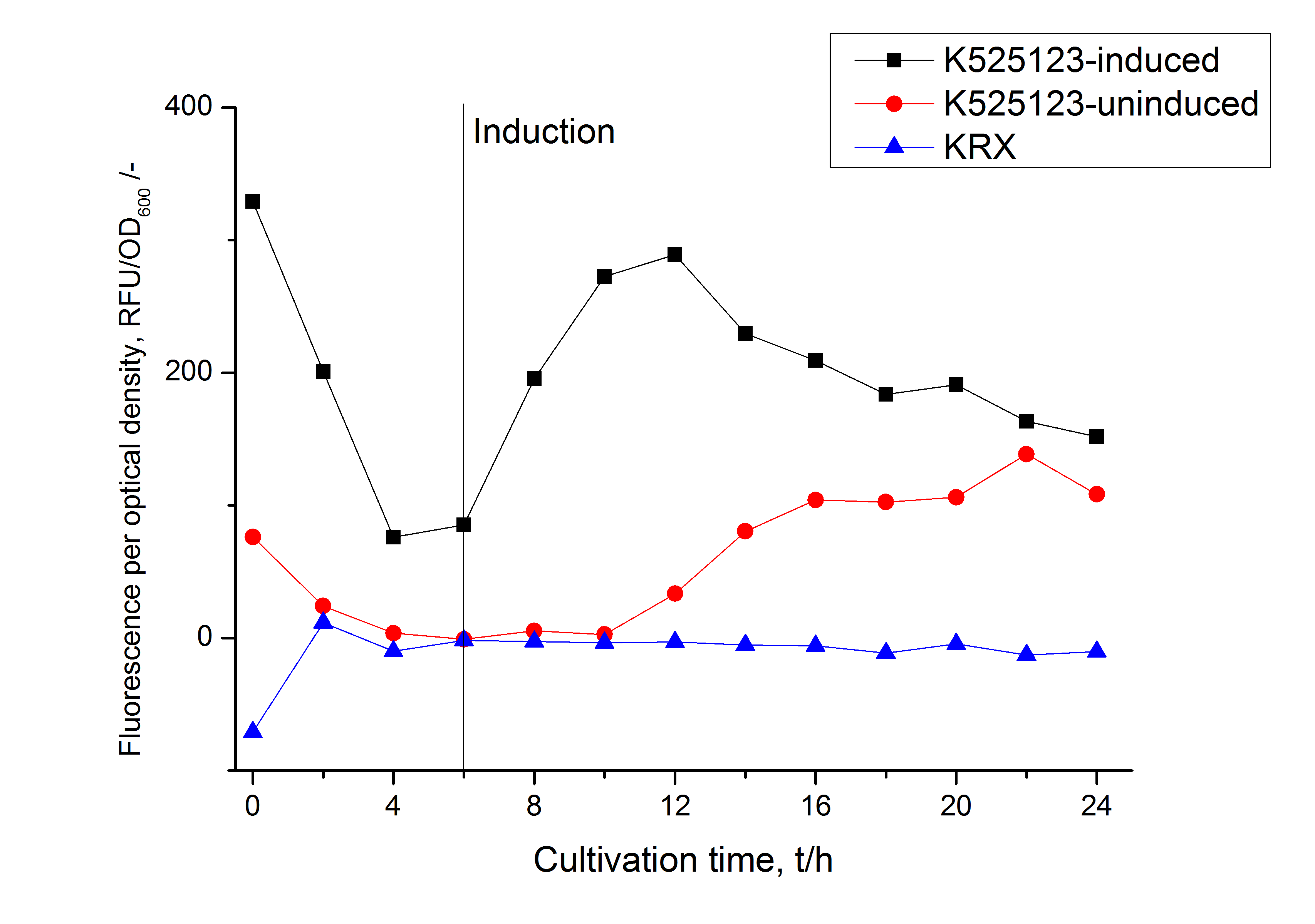

For characterization the modiefied CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525123 (K525123)] gen was fused with a monomeric RFP [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 (BBa_E1010)] using Gibson assembly.

The fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the autoinduction protocol.

Identification and localisation

CspB from Corynebacterium halotolerans

CspB without TAT-sequence and lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

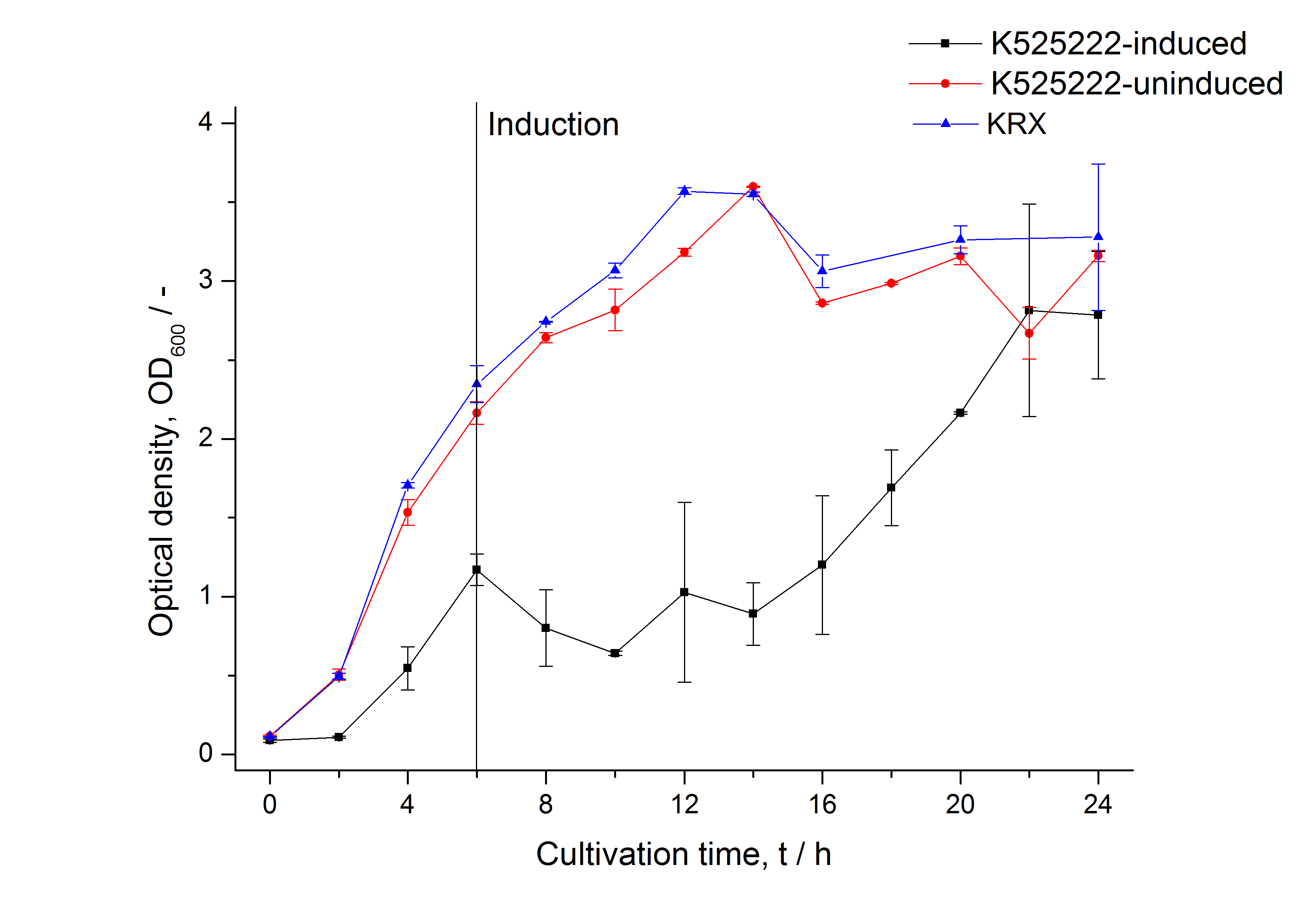

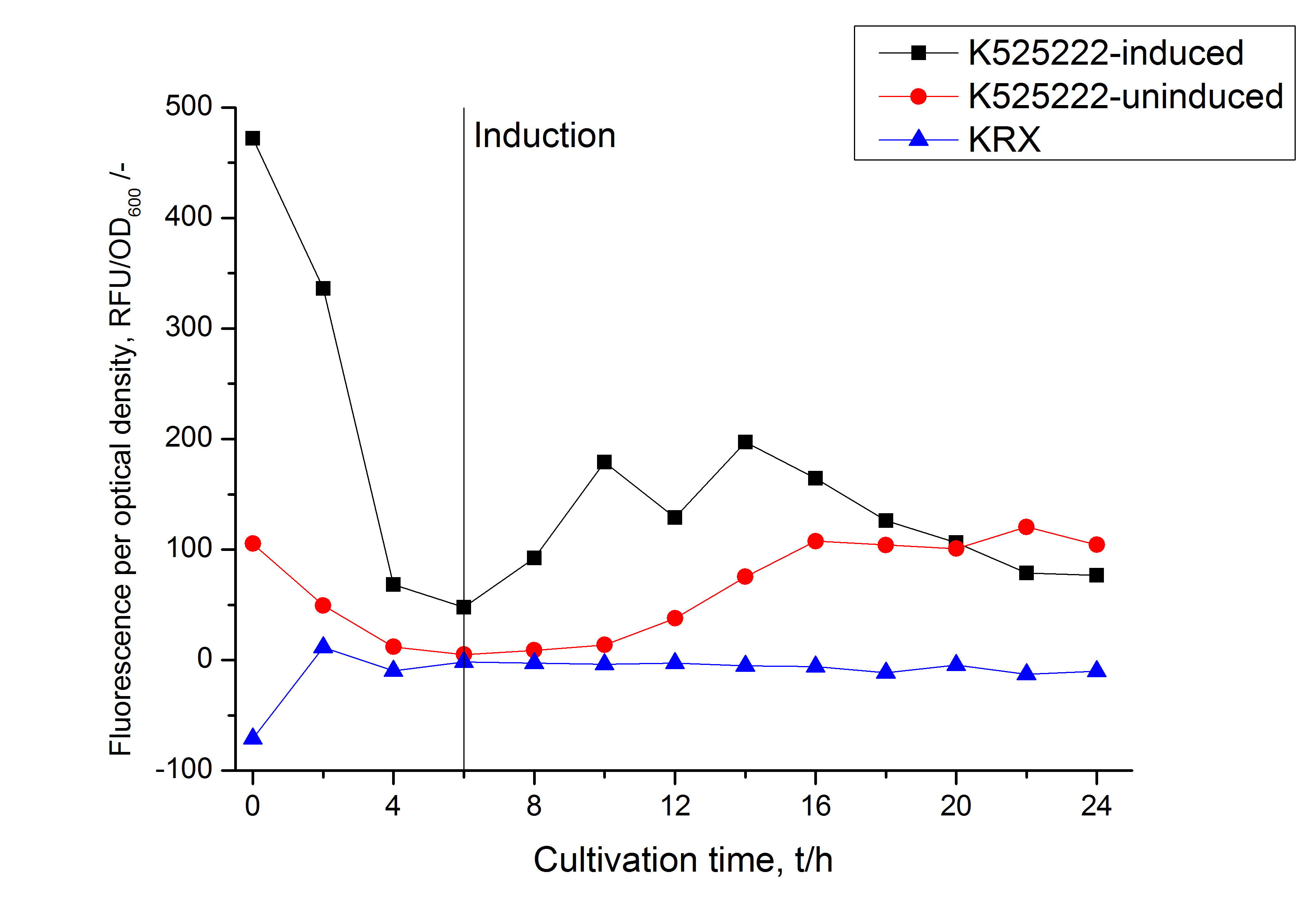

For characterization the modiefied CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525222 (K525222)] gen was fused with a monomeric RFP ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 BBa_E1010]) using Gibson assembly.

The fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the auinduction protocol.

Identification and localisation

CspB without TAT-sequence and with lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

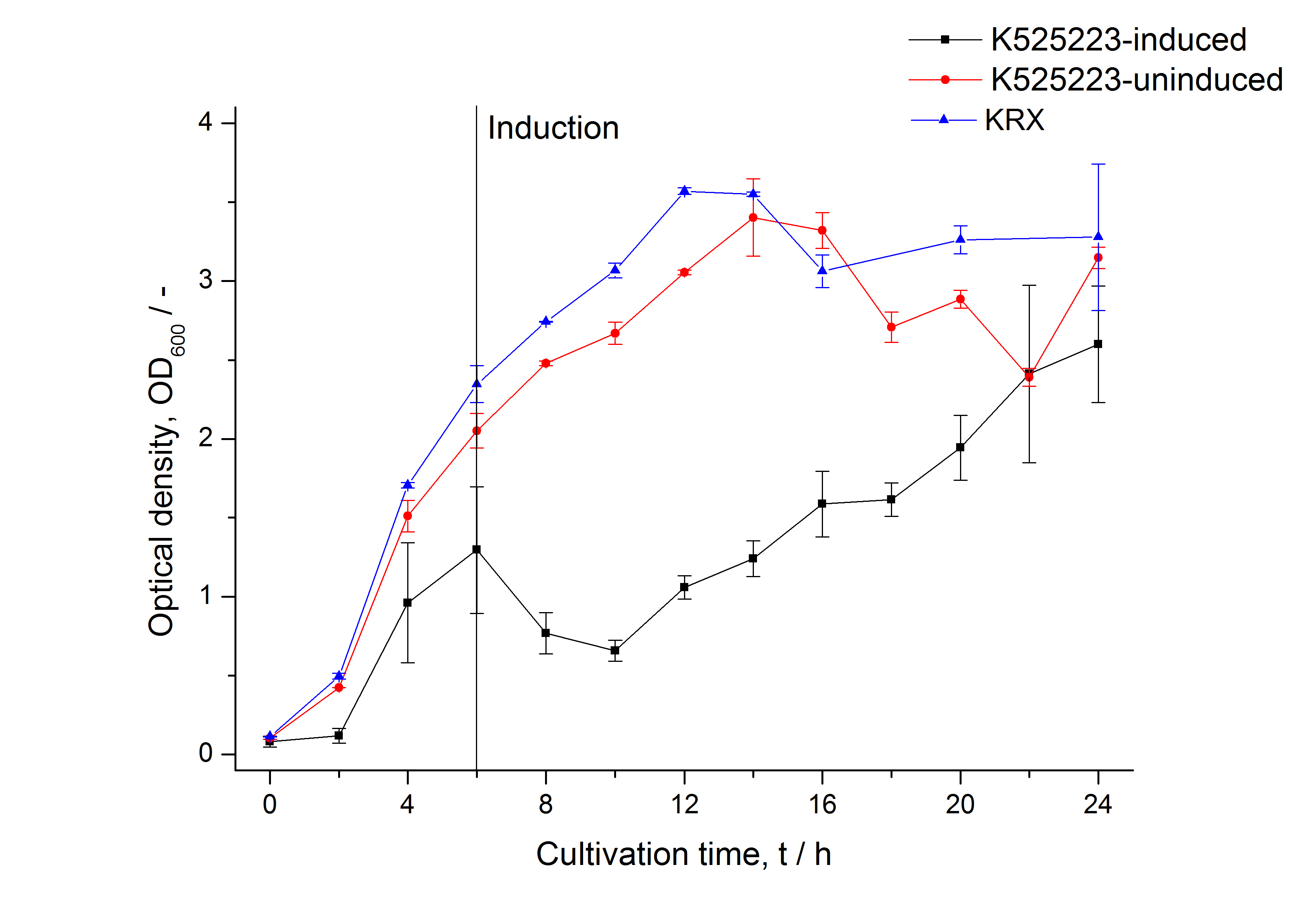

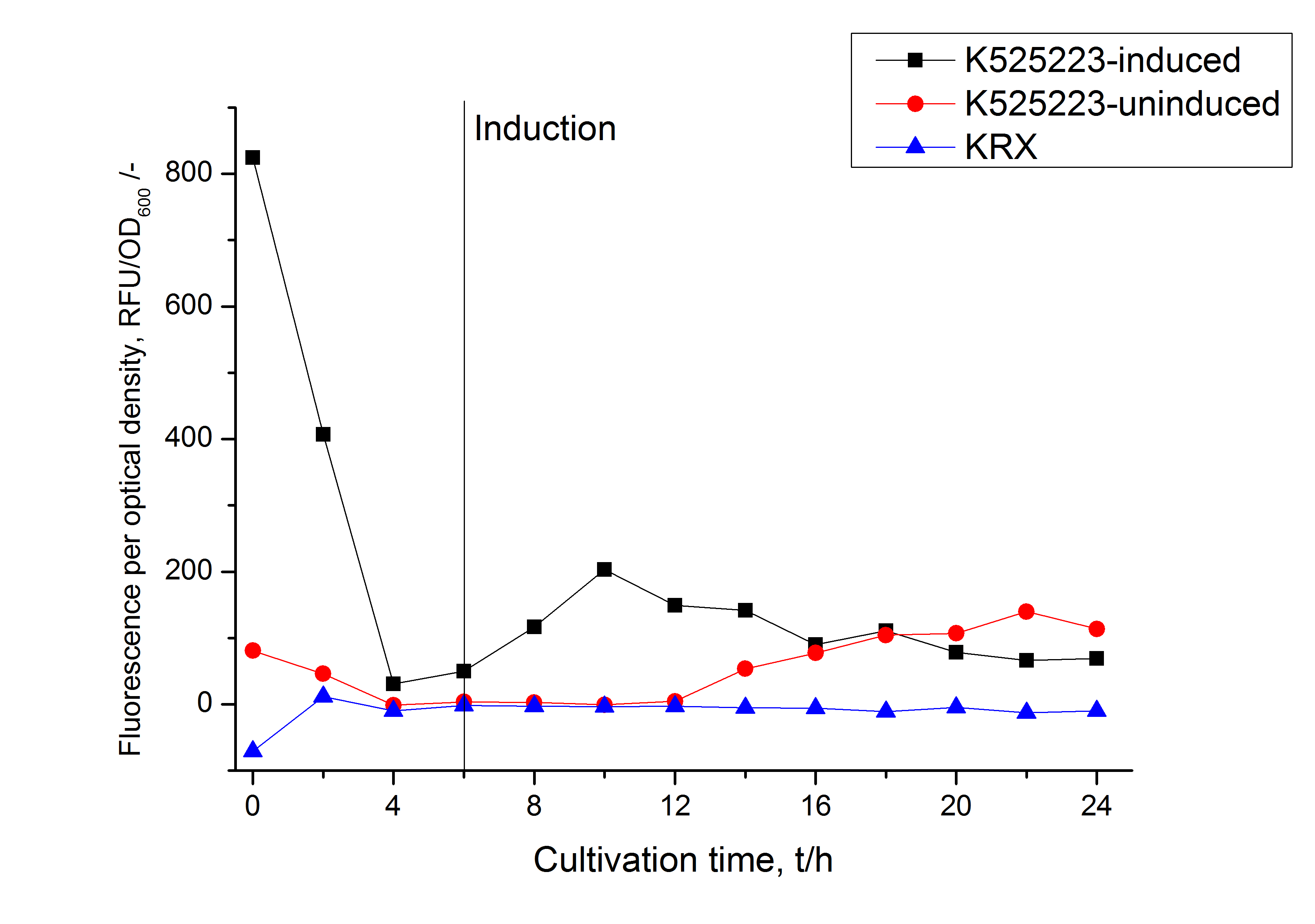

For characterization the modiefied CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525223 (K525223)] gen was fused with a monomeric RFP ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 BBa_E1010]) using Gibson assembly.

The fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the auinduction protocol.

Identification and localisation

CspB with TAT-sequence and without lipid anchor

Cultivation and protein expression

For characterization the modiefied CspB [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K525224 (K525224)] gen was fused with a monomeric RFP ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 BBa_E1010]) using Gibson assembly.

The fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli KRX after induction of T7 polymerase by supplementation of 0,1 % L-rhamnose using the auinduction protocol.

Identification and localisation

Purification

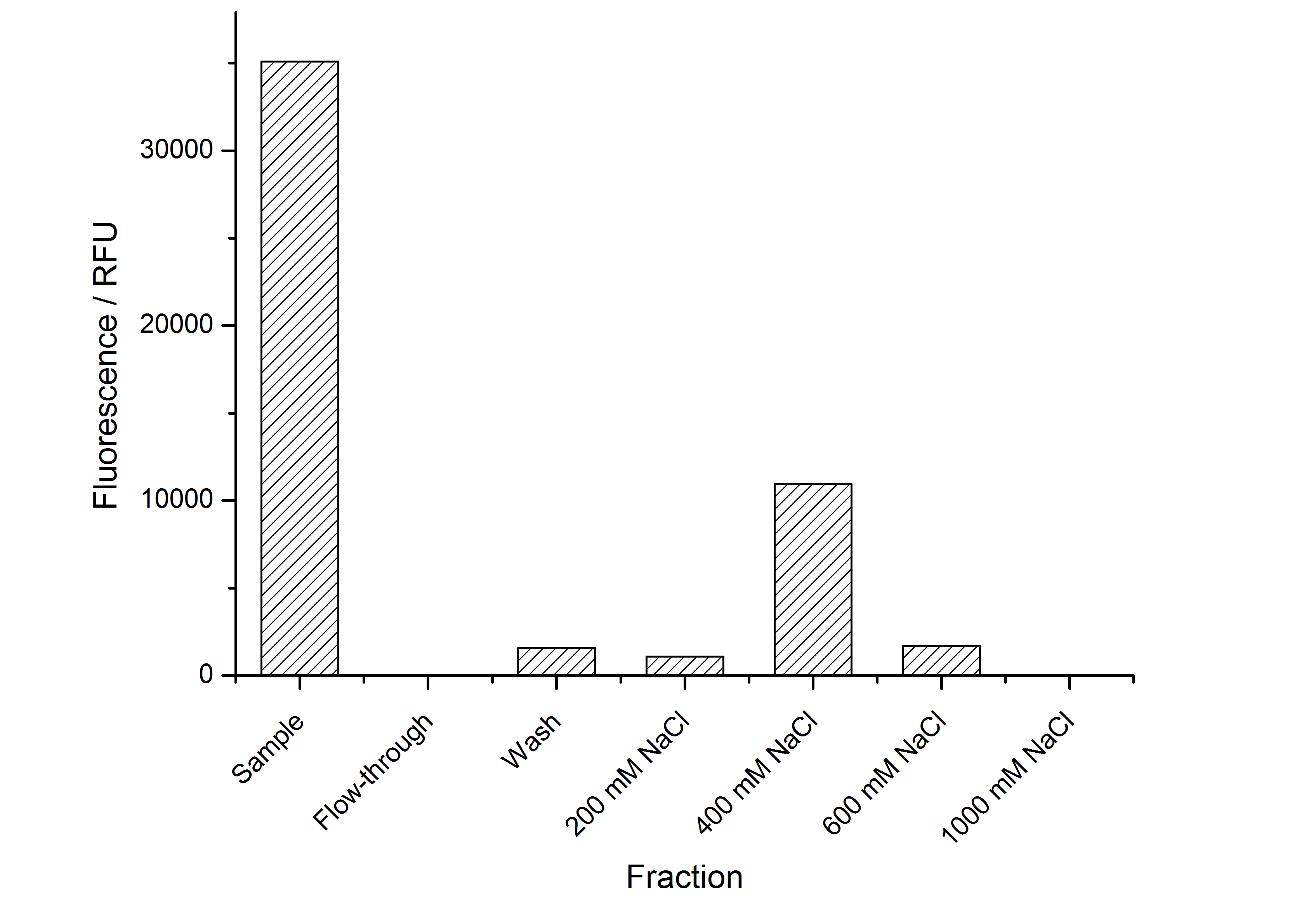

After the localisation of the S-layer protein in E. coli, different methods for purification were tested. The results of these methods are shown in fig. X. Fig. X shows, that the CspB protein does not form inclusion bodies in E. coli and most of the protein is transported out of the cell into the periplasm and a lot of protein is even secreted into the medium (all fractions were concentrated by filtration and precipitation, respectively). The secretion into the culture medium is very interesting because the purification is much faster (no cell disruption necessary).

The highest fluorescence could be obtained by a precipitation with ammonium sulfate of the culture supernatant followed by an ultrafiltration with a 300 kDa membrane and a diafiltration with a 50 kDa membrane. The diafiltration was against a binding buffer for an anion exchange chromatography (25 mM sodium acetate, 25 mM sodium chloride) with pH 6, due to the theoretical pI of <partinfo>k525234</partinfo>. The fluorescence of the collected fractions of the following anion exchange chromatography are shown in fig. B.

The binding conditions are well chosen because nearly all of the protein binds to the column. The protein is eluted from the column with rising sodium chloride concentrations. The highest fluorescence is in the elution fraction with 400 mM sodium chloride. 600 mM sodium chloride elutes all of the S-layer fusion proteins.

Final purification strategy

Scheme of purification strategy for CspB (fusion) proteins without lipid anchor:

First, CspB is expressed in E. coli under the control of a T7 promoter for separation of growth and production phase due to metabolic stress of the S-layer expression. Because the CspB protein with TAT-sequence and without lipid anchor is secreted to the culture medium in appreciable amounts by E. coli, an ammonium sulfate precipitation of the culture supernatant follows the cultivation. The S-layers are further concentrated and purified by two ultrafiltration / diafiltration steps (300 kDa and 100 kDa) with anion exchange chromatography binding buffer. The permeate of the last filtration is used for an anion exchange chromatography for capture and purification of the S-layer protein.

Click for detailed information

"

"