Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Project/Background/BPA

From 2011.igem.org

(→Bisphenol A degradation) |

(→Further applications of bisphenol A degrading BioBricks and enzymes) |

||

| (One intermediate revision not shown) | |||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

The three gene products responsible for hydroxylating BPA act together to reduce BPA while oxidizing NADH. The cytochrome P450 (BisdB) reduces the BPA and is oxidized during this reaction. BisdB in its oxidized status is reduced by the ferredoxin (BisdA) so it can reduce BPA again. The oxidized BisdA is reduced by a ferredoxin-NAD<sup>+</sup> oxidoreductase consuming NADH so that the BPA degradation can continue ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki ''et al.'', 2005b]). The ''bisdAB'' genes from ''S. bisphenolicum'' AO1 were isolated, transformed into and expressed in ''E. coli'' and by this enabled ''E. coli'' to degrade BPA ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03843.x/full Sasaki ''et al.'', 2008]). In addition, the BisdAB proteins from ''S. bisphenolicum'' AO1 were used to degrade BPA in a cell-free system (enzyme assay) in which spinach reductase ([http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/EC1/18/1/2.html EC 1.18.1.2]) was added ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki ''et al.'', 2005b]). | The three gene products responsible for hydroxylating BPA act together to reduce BPA while oxidizing NADH. The cytochrome P450 (BisdB) reduces the BPA and is oxidized during this reaction. BisdB in its oxidized status is reduced by the ferredoxin (BisdA) so it can reduce BPA again. The oxidized BisdA is reduced by a ferredoxin-NAD<sup>+</sup> oxidoreductase consuming NADH so that the BPA degradation can continue ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki ''et al.'', 2005b]). The ''bisdAB'' genes from ''S. bisphenolicum'' AO1 were isolated, transformed into and expressed in ''E. coli'' and by this enabled ''E. coli'' to degrade BPA ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03843.x/full Sasaki ''et al.'', 2008]). In addition, the BisdAB proteins from ''S. bisphenolicum'' AO1 were used to degrade BPA in a cell-free system (enzyme assay) in which spinach reductase ([http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/EC1/18/1/2.html EC 1.18.1.2]) was added ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki ''et al.'', 2005b]). | ||

| - | In 2008, the iGEM team from the [https://2008.igem.org/Team:The_University_of_Alberta/Parts University of Alberta] submitted the ''bisdAB'' genes from ''S. bisphenolicum'' AO1 to the [http://partsregistry.org/Main_Page registry of standard biological parts] in the so-called [http://partsregistry.org/Assembly_standard_25 Freiburg BioBrick assembly standard] (<partinfo>K123000</partinfo> and <partinfo>K123001</partinfo>). In order to degrade BPA in a cell-free system, also a FNR BioBrick is needed. As demonstrated, the BisdA and BisdB work together in a cell-free system with spinach reductase and they work intracellular in ''E. coli''. Thus, it can be assumed that it is possible to produce all components necessary to degrade BPA in a cell-free system in ''E. coli''. To achieve this, a ferredoxin-NADP<sup>+</sup> oxidoreductase BioBrick, isolated from ''E. coli'', is provided by the Bielefeld-Germany 2011 iGEM team (<partinfo>K525499</partinfo>). We were also able to construct the fusion protein <partinfo>K525560</partinfo>, which consists of <partinfo>K123000</partinfo>, <partinfo>K123001</partinfo> and <partinfo>K525499</partinfo>. | + | In 2008, the iGEM team from the [https://2008.igem.org/Team:The_University_of_Alberta/Parts University of Alberta] submitted the ''bisdAB'' genes from ''S. bisphenolicum'' AO1 to the [http://partsregistry.org/Main_Page registry of standard biological parts] in the so-called [http://partsregistry.org/Assembly_standard_25 Freiburg BioBrick assembly standard] (<partinfo>K123000</partinfo> and <partinfo>K123001</partinfo>). In order to degrade BPA in a cell-free system, also a FNR BioBrick is needed. As demonstrated, the BisdA and BisdB work together in a cell-free system with spinach reductase and they work intracellular in ''E. coli''. Thus, it can be assumed that it is possible to produce all components necessary to degrade BPA in a cell-free system in ''E. coli''. To achieve this, a ferredoxin-NADP<sup>+</sup> oxidoreductase BioBrick, isolated from ''E. coli'', is provided by the Bielefeld-Germany 2011 iGEM team (<partinfo>K525499</partinfo>). We were also able to construct the fusion protein <partinfo>K525560</partinfo>, which consists of <partinfo>K123000</partinfo>, <partinfo>K123001</partinfo> and <partinfo>K525499</partinfo>. |

The whole electron transport chain built by the three enzymes involved in BPA degradation and the BioBricks needed to enable this reaction ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro'' are shown in the following figure (please have some patience, it is an animated .gif file): | The whole electron transport chain built by the three enzymes involved in BPA degradation and the BioBricks needed to enable this reaction ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro'' are shown in the following figure (please have some patience, it is an animated .gif file): | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

==Further applications of bisphenol A degrading BioBricks and enzymes== | ==Further applications of bisphenol A degrading BioBricks and enzymes== | ||

| - | Beside the use in a biosensor, BPA degrading BioBricks could mainly be used in bioremediation approaches in BPA contaminated water or soil. If it was possible to determine and isolate the genes which are responsible for the complete degradation of BPA to substrates that can be used by bacteria as a carbon source, it would enable the bacterium carrying these BioBricks to grow on BPA. This device under the control of a BPA inducible promoter, transformed into bacteria living in a BPA contaminated environment, would be a selective advance making other selection markers such as antibiotic resistance unnecessary. For bioremediation approaches this would be an interesting advance because genes for antibiotic resistances | + | Beside the use in a biosensor, BPA degrading BioBricks could mainly be used in bioremediation approaches in BPA contaminated water or soil. If it was possible to determine and isolate the genes which are responsible for the complete degradation of BPA to substrates that can be used by bacteria as a carbon source, it would enable the bacterium carrying these BioBricks to grow on BPA. This device under the control of a BPA inducible promoter, transformed into bacteria living in a BPA contaminated environment, would be a selective advance making other selection markers such as antibiotic resistance unnecessary. For bioremediation approaches this would be an interesting advance, because genes for antibiotic resistances which could potentially be passed to other bacteria via bacterial conjugation, are not released into the environment. The release of antibiotic resistance genes always bears the danger that these find a way into pathogenic bacteria strains creating multi-drug-resistant pathogens. A device which enables bacteria to grow on BPA as the only carbon source would not generate this risk in bacterial-based bioremediation approaches and therefore enhances the biosecurity of such an approaches. |

=References= | =References= | ||

Latest revision as of 21:21, 28 October 2011

Contents |

Bisphenol A

The organic compound bisphenol A (BPA) is a key monomer in the production of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins. Since polycarbonate is clear, heat stable and nearly shatter-proof, it is used in many common products like baby and water bottles, electronics, CDs/DVDs and eyeglass lenses. Epoxy resins are used as coatings on the inside of almost all food and beverage cans. BPA monomers can leak in small doses from these plastics into aqueous solutions. This leads to a daily exposure to BPA. Due to safety concerns, BPA use in the production of baby bottles is forbidden in the European Union and in Canada.

Bisphenol A and its effects on mammals

Due to the leaking of BPA monomers into aqueous solutions from BPA containing plastics, it may be absorbed by humans or eventually contaminate the environment. The exposure of BPA-based platics to heat under acidic or basic conditions accelarates the hydrolysis of the ester-bonds between the BPA monomers resulting in an increased release of BPA ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Richter et al., 2007]). It has been shown that the exposure to even low doses of BPA during development has persistent effects ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Richter et al., 2007]).

Bisphenol A acts as endocrine disruptor, because it mimics the natural hormone estrogen and may thus induce negative health effects. It can bind in vivo and in vitro to estrogen receptors (ER) which leads to alterations in several levels of tissues and cells. The consequences are changes in estrogen-targeted cells in such as the brain and the mammary glands. In addition, BPA acts on non-classical targets like bones, cardiovascular tissue, pancreas, adipose tissue and the immune system ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2647705/ Vandenberg et al., 2009]). There is also evidence indicating an anti-tyroid hormone effect ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Richter et al., 2007]). A study of the BPA concentration in urine shows a significant relationship to cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and liver-enzyme abnormalities in adults ([http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/300/11/1303/ Lang et al., 2008]).

Another estrogenic effect of BPA is the disruption of pancreas ß-cells, resulting in an insulin resistance. Furthermore, it leads to an increase in glucose transporter GLUT4 and thus to glucose uptake in cells ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Richter et al., 2007]). BPA can also have an effect on the immune system, dependending on the time of exposure, as it affects the estrogen receptor that is expressed by lymphocytes dependent on age and gender ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Richter et al., 2007]).

Moreover, studies provide evidence that indicate an effect on male and female reproductive tracts. In males, it has an impact on sperm production, testosterone secretion and on reproductive structures (e.g. the prostate). These effects can already be observed under admission of low BPA doses. The effect on the adult male reproductive tract has adverse consequences for the testicular function. In the long run, this can lead to infertility. In case of females, alterations in the development of the mammary glands and their structure could be determined which might be a reason for cancer development ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Richter et al., 2007]).

Bisphenol A degradation

Many naturally occurring bacteria can degrade xenobiotic substances such as phenolic compounds or endocrine disruptors. In soil samples, taken from contaminated soil to find organisms that degrade such substances, Sphingomonas species were extraordinarily often isolated ([http://www.springerlink.com/content/t717l15u85507706/ Stolz, 2009]). In 2005, [http://www.springerlink.com/content/q7864l02734wg32m/ Sasaki et al.] isolated a soil bacterium from the Sphingomonas genus which is able to degrade the endocrine disruptor bisphenol A (BPA) with an unique rate and efficiency compared to other BPA degrading organisms. This strain, called Sphingomonas bisphenolicum AO1, is able to completely decompose 120 mg BPA L-1 in about 6 h while other strains need days of cultivation (e.g. Sphingomonas strain BP-7 isolated by [http://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bbb/71/1/71_51/_article Sakai et al. (2007)]).

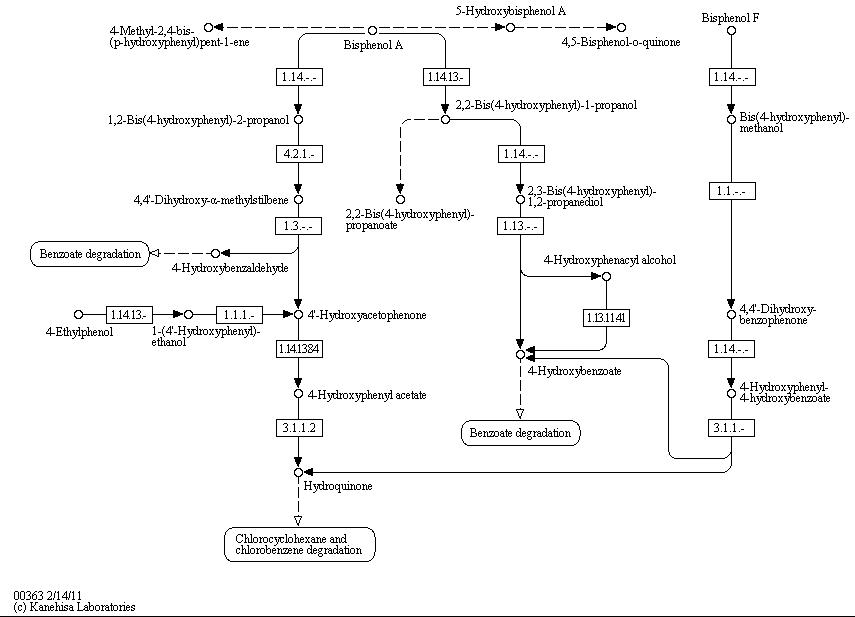

The full bisphenol A degradation pathway which is found in nature is shown in Figure 1 (taken from KEGG database). BPA is metabolized to 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 4'-hydroxyacetophenone and 4-hydroxybenzoate which can be used by some bacteria as a carbon source. These and other metabolites of the BPA degradation pathway can be found in the supernatant of cultivations of S. bisphenolicum AO1 containing BPA. Furthermore, this bacteria can grow on BPA as the only a carbon source ([http://www.springerlink.com/content/q7864l02734wg32m/ Sasaki et al., 2005a]).

Bisphenol A is mainly hydroxylated into the products 1,2-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol and 2,2-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol by some kind of oxidoreductase dependent on NADH or NADPH. In S. bisphenolicum AO1, a total of three genes were identified that are responsible for this BPA hydroxylation: a cytochrome P450 (CYP, bisdB), a ferredoxin (Fd, bisdA) and a ferredoxin-NAD+ oxidoreductase (FNR) ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki et al., 2005b]). Common class I electron transport systems for bacterial cytochrome P450 consist of these three enzymes mentioned above, mostly using a ferredoxin with a [2Fe-2S] iron-sulfur cluster ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304416506002133 Hannemann et al., 2007]). In addition, class V electron transport systems were found in bacteria, composed of a ferredoxin-cytochrome P450 fusion protein and a NAD(P)H-ferredoxin oxidoreductase. In these systems, the ferredoxin is fused to the N-terminus of the cytochrome P450 via a linker region ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304416506002133 Hannemann et al., 2007]). The three proteins mentioned above were isolated separately from S. bisphenolicum AO1 ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki et al., 2005]), so the CYPbisd electron transport system is a bacterial class I system.

The three gene products responsible for hydroxylating BPA act together to reduce BPA while oxidizing NADH. The cytochrome P450 (BisdB) reduces the BPA and is oxidized during this reaction. BisdB in its oxidized status is reduced by the ferredoxin (BisdA) so it can reduce BPA again. The oxidized BisdA is reduced by a ferredoxin-NAD+ oxidoreductase consuming NADH so that the BPA degradation can continue ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki et al., 2005b]). The bisdAB genes from S. bisphenolicum AO1 were isolated, transformed into and expressed in E. coli and by this enabled E. coli to degrade BPA ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03843.x/full Sasaki et al., 2008]). In addition, the BisdAB proteins from S. bisphenolicum AO1 were used to degrade BPA in a cell-free system (enzyme assay) in which spinach reductase ([http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/EC1/18/1/2.html EC 1.18.1.2]) was added ([http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Sasaki et al., 2005b]).

In 2008, the iGEM team from the University of Alberta submitted the bisdAB genes from S. bisphenolicum AO1 to the [http://partsregistry.org/Main_Page registry of standard biological parts] in the so-called [http://partsregistry.org/Assembly_standard_25 Freiburg BioBrick assembly standard] (<partinfo>K123000</partinfo> and <partinfo>K123001</partinfo>). In order to degrade BPA in a cell-free system, also a FNR BioBrick is needed. As demonstrated, the BisdA and BisdB work together in a cell-free system with spinach reductase and they work intracellular in E. coli. Thus, it can be assumed that it is possible to produce all components necessary to degrade BPA in a cell-free system in E. coli. To achieve this, a ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase BioBrick, isolated from E. coli, is provided by the Bielefeld-Germany 2011 iGEM team (<partinfo>K525499</partinfo>). We were also able to construct the fusion protein <partinfo>K525560</partinfo>, which consists of <partinfo>K123000</partinfo>, <partinfo>K123001</partinfo> and <partinfo>K525499</partinfo>.

The whole electron transport chain built by the three enzymes involved in BPA degradation and the BioBricks needed to enable this reaction in vivo and in vitro are shown in the following figure (please have some patience, it is an animated .gif file):

Further applications of bisphenol A degrading BioBricks and enzymes

Beside the use in a biosensor, BPA degrading BioBricks could mainly be used in bioremediation approaches in BPA contaminated water or soil. If it was possible to determine and isolate the genes which are responsible for the complete degradation of BPA to substrates that can be used by bacteria as a carbon source, it would enable the bacterium carrying these BioBricks to grow on BPA. This device under the control of a BPA inducible promoter, transformed into bacteria living in a BPA contaminated environment, would be a selective advance making other selection markers such as antibiotic resistance unnecessary. For bioremediation approaches this would be an interesting advance, because genes for antibiotic resistances which could potentially be passed to other bacteria via bacterial conjugation, are not released into the environment. The release of antibiotic resistance genes always bears the danger that these find a way into pathogenic bacteria strains creating multi-drug-resistant pathogens. A device which enables bacteria to grow on BPA as the only carbon source would not generate this risk in bacterial-based bioremediation approaches and therefore enhances the biosecurity of such an approaches.

References

Lang IA, Galloway TS, Scarlett A, Henley WE, Depledge M, Wallace RB, Melzer D (2008) Association of Urinary Bisphenol A Concentration With Medical Disorders and Laboratory Abnormalities in Adults, [http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/300/11/1303/ JAMA 300(11)].

Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, Sonnenschein C, Rubin BS, Soto AM (2009) Bisphenol-A and the Great Divide: A Review of Controversies in the Field of Endocrine Disruption, [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2647705/ Endocrine Reviews 30(1):75–95].

Richter CA, Birnbaum LS, Farabollini F, Newbold RR, Rubin BS, Talsness CE, Vandenbergh JG, Walser-Kuntz DR, vom Saal FS (2007) In Vivo Effects of Bisphenol A in Laboratory Rodent Studies [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2151845/ Reprod Toxicol 24(2): 199–224].

Hannemann F, Bichet A, Ewen KM, Bernhardt R (2007) Cytochrome P450 systems—biological variations of electron transport chains, [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304416506002133 Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1770(3):330-344].

Sakai K, Yamanaka H, Moriyoshi K, Ohmoto T, Ohe T (2007) Biodegradation of Bisphenol A and Related Compounds by Sphingomonas sp. Strain BP-7 Isolated from Seawater, [http://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bbb/71/1/71_51/_article Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 71(1):51-57].

Sasaki M, Maki J, Oshiman K, Matsumura Y, Tsuchido T (2005a) Biodegradation of bisphenol A by cells and cell lysate from Sphingomonas sp. strain AO1, [http://www.springerlink.com/content/q7864l02734wg32m/ Biodegradation 16(5):449-459].

Sasaki M, Akahira A, Oshiman K, Tsuchido T, Matsumura Y (2005b) Purification of Cytochrome P450 and Ferredoxin, Involved in Bisphenol A Degradation, from Sphingomonas sp. Strain AO1, [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/71/12/8024 Appl Environ Microbiol 71(12):8024-8030].

Sasaki M, Tsuchido T, Matsumura Y (2008) Molecular cloning and characterization of cytochrome P450 and ferredoxin genes involved in bisphenol A degradation in Sphingomonas bisphenolicum strain AO1, [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03843.x/full J Appl Microbiol 105(4):1158-1169].

Stolz A (2009) Molecular characteristics of xenobiotic-degrading sphingomonads, [http://www.springerlink.com/content/t717l15u85507706/ Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 81:793-811].

"

"