Team:ETH Zurich/Biology/Detector

From 2011.igem.org

(→How we used it) |

|||

| (250 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/ | + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/HeaderNew}} |

| - | { | + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} |

| - | + | = Network Elements = | |

| - | + | '''SmoColi can be divided into different network elements: the major sub-networks being a sensor, a band-pass filter and a quorum sensing mechanism. | |

| - | + | <br> <br> | |

| - | + | Cigarette smoke contains a lot of different toxic and carcinogenic components. In nature there are many sensors for such components, mostly to induce their degradation. One is the acetaldehyde system in ''aspergillus nidulans'': the activator AlcR binds to its operator site if acetaldehyde is present [[#Ref1|[1]]]. Another one is the xylene sensing system in ''Pseudomonas putida'' [[#Ref2|[2]]] working as an activator. Since our system is constructed in a modular fashion an can be coupled with any sensor, an arabinose sensing system was established as a proof of principle. | |

| - | + | We combined a smoke-sensitive band-pass filter with GFP output with a quorum-sensing based mechanism alarming the user at high smoke levels by expressing RFP.''' | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | <center> | |

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <img src="/wiki/images/6/61/Moduls_of_SmoColi.png" usemap="#Moduls"/> | ||

| + | <map name="Moduls"> | ||

| + | <area shape="rect" alt="" title="" coords="4,46,332,114" href="#Acetaldehyde_Sensor" target="" /> | ||

| + | <area shape="rect" alt="" title="" coords="342,46,432,112" href="#Inverter" target="" /> | ||

| + | <area shape="rect" alt="" title="" coords="2,114,430,182" href="#Xylene_Sensor" target="" /> | ||

| + | <area shape="rect" alt="" title="" coords="4,188,430,252" href="#Arabinose_Sensor" target="" /> | ||

| + | <area shape="rect" alt="" title="" coords="444,4,610,250" href="#Bandpass" target="" /> | ||

| + | <area shape="rect" alt="" title="" coords="612,2,718,252" href="#Quorum_Sensing_of_the_Alarm_system" target="" /> | ||

| + | </map> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| - | + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | |

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| - | == | + | =Acetaldehyde Sensor = |

| + | === Where it comes from... === | ||

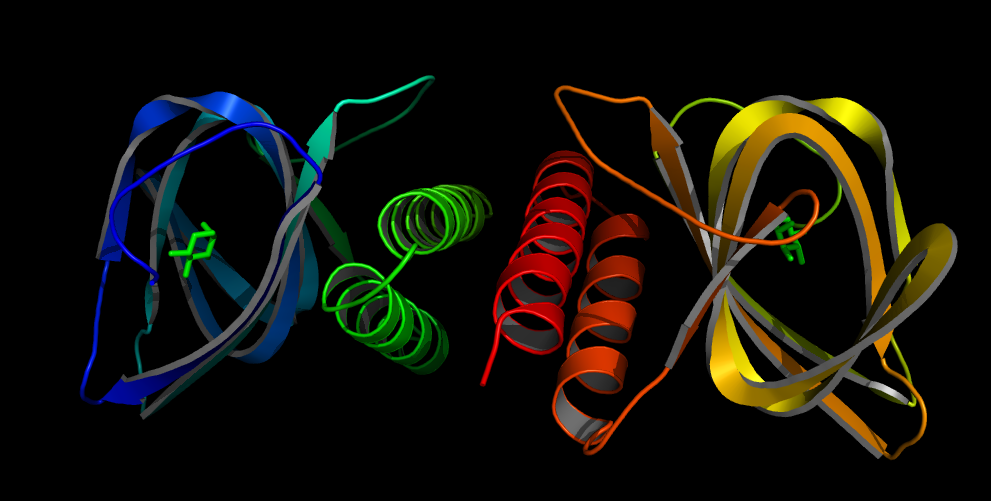

| + | [[File:AlcR.png|200px|right|thumb|'''Figure 1: Structures of the AlcR(1-60)-DNA complex''' [[#Ref13|[13]]] ]] | ||

| + | In ''Aspergillus nidulans'', the ''alcR'' gene encodes a regulatory protein which activates the expression of the ethanol utilization (alc) pathway if the co-inducer acetaldehyde is present. Ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde by the alcohol dehydrogenase and further metabolized to acetate by the aldehyde dehydrogenase. Both genes ''alcA'' and ''aldA'' are regulated by AlcR. AlcR also regulates its own expression by autoactivation [[#Ref1|[1]]]. | ||

| + | The AlcR DNA binding domain contains a zinc bi-nuclear cluster, which can bind either to symmetric and asymmetric sites with same affinity. In contrast to other members of the Zn<sub>2</sub>Cys<sub>6</sub>, the DNA binding domain is stretch of 16 amino acid residues between the third and fourth cysteine. AlcR binds as a monomer, but 2 proteins can bind to inverted repeats in a noncooperative manner. Additional DNA sequences upstream of the zinc cluster were identified to be responsible for high-affinity binding, [[#Ref4|[4]]]. | ||

| + | <br clear="all" /> | ||

| - | + | === How we used it === | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | Because fungal activators normally do not work in ''E. coli'', the system was modified to work as a bacterial repressor. The mechanism of how AlcR activates transcription is not completely known, which makes the process of redesigning it very challenging. A second challenge is the different codon usage in ''Apergillus nidulans'' and ''E. coli''. The codon adaptation index (CAI) of ''Aspergillus nidulans'' AlcR is 0.7 in ''E. coli'', especially at the beginning of the gene a few very rare codons are present. To get a fully ''E. coli''-optimized gene, we ordered the gene codon-optimized. To get a partly codon-optimized version, we exchanged the rare codons at the beginning of the ''Aspergillus nidulans'' protein with PCR. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | [[File:AlcR_Promotordesign.png|300px|left|thumb|'''Figure 2: Design of the promoter for the AlcR-system in SmoColi''', the operon sequence is designed between the -10 and the -35 region (blue) of a strong promoter with inverted and direct repeats.]] | |

| - | | | + | <span id="AlcR_Promoter">For</span> a redesigned bacterial P<sub>Alc</sub> promoter, natural operator sites of AlcR from ''Aspergillus nidulans'' were placed between the -10 and -35 region of a constitutive ''E.coli'' promoter. Two versions of the synthetic promoter were implemented, one with direct-repeat targets and one with inverted [[#Ref1|[1]]]. The idea is that in the presence of acetaldehyde, AlcR will bind to the operon and block the binding of the RNA polymerase. This only works if the mechanism of AlcR transcriptional activation is based on acetaldehyde induced DNA binding and does not just involve conformational changes. When implementing the SmoColi genetic network, an additional inverter (TetR) is added in front of the bandpass, so that the acetaldehyde signal is passed into the bandpass in a positive way. Thus the AlcR promoter (P<sub>Alc</sub>) is cloned in front of the TetR repressor to introduce the bandpass. |

| - | = | + | |

| - | + | <br clear="all" /> | |

| + | [[File:Design2.png|400px|right|thumb|'''Figure 3: Circuit operations for SmoColi with acetaldehyde sensor''', AlcR works as an repressor, therefore a inverter (TetR) is introduced to convert the repression of the input to an activation.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Acetaldehyde is reduced by the native ''E. coli'' enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase, generating a concentration gradient in our tube. At the position with the required concentration of acetaldehyde for the bandpass-filter, GFP is expressed, at all other positions it is repressed, resulting in a single GFP band. By tuning the input of acetaldehyde in the tube, we get the GFP band at different positions. Thus, with constantly increasing acetaldehyde concentration, we get a moving band from one side to the other side of the channel. Finally,if the acetaldehyde concentration exceeds a certain threshold, the whole channel turns red, due to the quorum-sensing based RFP expression. | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| - | + | = Xylene Sensor = | |

| - | + | === Where it comes from... === | |

| - | + | The ''xylR'' gene in ''Pseudomonas putida'' encodes a 566 aa regulatory protein that activates the degradation of toluene and xylene. In ''P. putida'' the complete upper Tol pathway is under the control of the toluene-responsive promoter P<sub>U</sub>. In the presence of xylene, XylR hexamerically binds to P<sub>U</sub> promoter and activates it [[#Ref5|[5]]]. This activates expression of the xylene degradation cassette ''xylC-xylM-xylA-xylB-xylN'', where ''xylC'' encodes for the benzaldehyde dehydrogenase, ''xylM'' and ''xylA'' for subunits of the xylene oxygenase and ''xylB'' for benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase [[#Ref6|[6]]]. XlyN is not required for the degradation of xylene, but it is part of the whole transcriptional unit. The DNA binding of XylR occurs at a 40 bp upstream activating sequence (UAS) located 150 bp upstream from the transcriptional start site of the σ<sup>54</sup> P<sub>U</sub> promoter. DNA looping between the UAS and the -12/-24 motifs of the σ<sup>54</sup>-RNAP facilitates the activation of the holoenzyme by XylR [[#Ref7|[7]]]. | |

| - | | | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | === How we used it === | |

| - | + | [[File:Alternative_Xylene_system.png|400px|left|thumb|'''Figure 4: Circuit operations of SmoColi with xylene sensor''' ]] | |

| + | Xylene is not degraded naturally by ''E. coli''. To generate a concentration gradient of xylene we engineered its degradation in SmoColi by including the upper Tol pathway. XylR is a prokaryotic enhancer binding protein, thus is completely functional in ''E. coli''. As an input into the SmoColi system, LacI<sub>M1</sub> and CI are put under the control of the P<sub>U</sub> promoter, enhancing their expression in the presence of xylene. | ||

| - | < | + | <br clear="all" /> |

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| - | <span id="Ref4">[4] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ | + | = Arabinose Sensor = |

| - | + | === Where it comes from... === | |

| + | [[File:ETH Arac.png|200px|right|thumb|'''Figure 5: Structures of the AraC heterodimere with L-Arabinose''' [[#Ref14|[14]]] ]] | ||

| + | The AraC regulatory protein is a activator of the genes for the araBAD, the ''araE'' and the ''araFGH'' operon in ''E.coli''. ''araB, araA'' and ''araD'' encode for the metabolic enzymes which degrade L-Arabinose to D-xylulose-5-phosphate. In absence of arabinose AraC does bind to two DNA site separated over 200 bp from each other (I<sub>1</sub> and O<sub>2</sub> of the P<sub>BAD</sub> promoter) [[#Ref8|[8]]]. By dimer formation of the two DNA bound AraC molecules the DNA is looped and transcription blocked. Binding of arabinose leads to binding of arabinose to I<sub>1</sub> and I<sub>2</sub>, I<sub>2</sub> bound AraC directly interacts with the RNA polymerase and activates it. ''araF, araG'' and ''araH'' and ''araE'' encode for proteins needed for uptake of arabinose. If some arabinose enters the cell, the uptake of arabinose is activated leading and more and more arabinose entering the cell. This positive feedback loop leads to an all or nothing response of arabinose in the cells. | ||

| + | <br clear="all" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === How we used it === | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Arabinose system.png|400px|left|thumb|'''Figure 6: Circuit operations of SmoColi with arabinose sensor''' ]] | ||

| + | To show that our system can be activated by different signals, we introduced a arabinose sensor. Due to the fact that AraC s well established in contract AlcR and XlyR, the arabinose system can be seen as proof of principle for the bandpass and the alarm system for our smoke sensors. The LacI<sub>M1</sub> and the CI regulators were under the control of the P<sub>BAD</sub> promoter, enhancing their expression in the presence of arabinose and the absence of glucose. | ||

| + | The all or nothing response of the arabinose system makes the natural system unusable for our bandpass, because we need an intermediate input signal. In order that we can still use the arabinose system we use the BW27783 (BW25113 DE(''araFGH'') Φ(∆''araEp'') (P<sub>CP8</sub>-''araE'')) ''E.coli'' strain [[#Ref9|[9]]]. This strain has a knock-out of the ''araBAD'' (degradation), ''araFGH'' (low capacity, high affinity transporter) and the promoter of the ''araE'' gene (high capacity, low affinity transporter) has been exchanged from P<sub>BAD</sub> to P<sub>CP8</sub>, which is a constitutive promoter. The elimination of the positive feedback loop within this strains leads to a titratable response on arabinose, allowingintermediate input concentrations for the bandpass filter. By inactivation of the kanamycin casette, we created the BW27783 from the BW27749, which was provided to us by Khlebnikov et al. (Done according to the method of: [[#Ref10|[10]]]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Bandpass = | ||

| + | === Where it comes from... === | ||

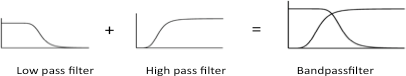

| + | [[File:ETH_Theory_Bandpass.png|500px|right|thumb|'''Figure 7: A Bandpassfilter''', is a combination of a high pass filter and a low pass filter.]] | ||

| + | In 2005 Ron Weiss et al. constructed the first band-pass filter device in synthetic biology. This was done by using the combination of a high-pass and a low-pass filter. An input signal is transmitted by cell to cell communication while the signal processing is done using an intracellular feed-forward loop. Filters are created by using different transcriptional regulator proteins with different repression efficiencies and binding affinities for corresponding promoters. | ||

| + | <br clear="all" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === How we used it === | ||

| + | |||

| + | We used his pioneering network design as a basis in the planning process for our band-pass filter implementation [[#Ref11|[11]]]. Instead of cell-cell communication via AHL for the input signal, we included our different smoke detectors which detect small volatile molecules like acetaldeyhde, xylene or arabinose. | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| + | |||

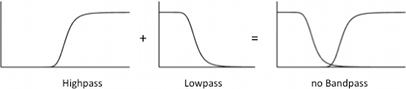

| + | = Inverter = | ||

| + | === Where it comes from... === | ||

| + | An inverter is a part which converts a repressor signal into an activator signal, or vise versa. For SmoColi we used TetR as an inverter. TetR binds and blocks the TetR promoter (P<sub>Tet</sub>, [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 BBa_R0040]). | ||

| + | <br clear="all" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === How we used it === | ||

| + | [[File:Noinverter.png|500px|right|thumb|'''Figure 8: What would happen without an inverter:''' No GFP formation..]] | ||

| + | When the inverter is not present, the band does not appear because the activation threshold of the high pass filter is at a higher value than the repression threshold of the low pass filter, thus there is no region where both branches produce an output signal. If the input signal (a repressor) is inverted we get again a nice bandpass filter. In our circuit the inverter is only needed for AlcR, for AraC and XylR the input signal is correct (they are already activators). | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Quorum Sensing of the Alarm system = | ||

| + | === Where it comes from... === | ||

| + | The luminescence operon in ''Vibrio fischeri'' is regulated by the transcriptional activator (LuxR). The lux box is a 20 bp inverted repeat sequence at a position centered 42.5 bases upstream of the transcriptional start. LuxR binds to the lux box in presents of AHL and enhance its expression. LuxR is needed to activate the σ<sup>70</sup> RNA Polymerase. The ''Vibrio fischeri'' lux operon consists of seven genes, the first one is ''luxI''. The ''luxI'' gene encodes for the enzyme for AHL synthesis. The autoinducer AHL is secreted by the cells to coordinate gene expression based on the local density of the bacterial population. Furthermore transcription of luciferase in the lux operon is induced, leading to bioluminescence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === How we used it === | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Lux Promoter.png|300px|right|thumb|'''Figure 9: Promoter for luxR''', the operon (red) designed between the -10 and the -35 region (blue) of the promoter.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | For our system we used a promoter which is repressed by luxR! ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0061 BBa_R0061]) It was designed by placing the lux box between and partially overlapping the consensus -35 and -10 site of an artificial lacZ promoter. In the presence of AHL, LuxR binds to the lux box and inhibits binding of the RNA Polymerase. [[#Ref12|[12]]] | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionStart}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = References = | ||

| + | <span id="Ref1">[1] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2834622 R. Locklngton, C. Scazzocchio, D. Sequeval, M. Mathieu, B. Felenbok: '''Regulation of alcR, the positive regulatory gene of the ethanol utilization regulon of Aspergillus nidulans''', Mol Microbiol., 1987, 1: 275-81]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref2">[2] [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/64/2/748 Sven Panke, Juan M. Sánchez-Romero, and Víctor de Lorenzo: '''Engineering of Quasi-Natural Pseudomonas putida Strains for Toluene Metabolism through an ortho-Cleavage Degradation Pathway''', Appl Environ Microbiol, 1998, 64: 748-751]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref3">[3] [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/64/6/2032 Sven Panke, Bernard Witholt, Andreas Schmid, and Marcel G. Wubbolts: '''Towards a Biocatalyst for (S)-Styrene Oxide Production: Characterization of the Styrene Degradation Pathway of Pseudomonas sp. Strain VLB120''', Appl Environ Microbiol, 1998, 64: 2032-2043]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref4">[4] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9182587 Lenouvel F, Nikolaev I, Felenbok B.: '''In vitro recognition of specific DNA targets by AlcR, a zinc binuclear cluster activator different from the other proteins of this class''', J Biol Chem. 1997, 272(24):15521-6.]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref5">[5] [http://www.springerlink.com/content/r65l105rg21t1l73/ Manabu Gomada, Sachiye Inouye, Hiromasa Imaishi, Atsushi Nakazawa and Teruko Nakazawa: '''Analysis of an upstream regulatory sequence required for activation of the regulatory gene xylS in xylene metabolism directed by the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida''', Molecular and General Genetics MGG, 1992, 233:419-426]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref6">[6] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC210316/ S Harayama, M Rekik, M Wubbolts, K Rose, R A Leppik, and K N Timmis:''' Characterization of five genes in the upper-pathway operon of TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida and identification of the gene products''', 1989, 171(9): 5048–5055] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref7">[7] [http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/31/23/6926.full Marc Valls and Víctor de Lorenzo: '''Transient XylR binding to the UAS of the Pseudomonas putida σ<sup>54</sup> promoter Pu revealed with high intensity UV footprinting in vivo''', Nucl. Acids Res., 2003, 31 (23): 6926-6934] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref8">[8] [http://gene.bio.jhu.edu/Ourspdf/108.pdf D. A. Hodgson, C. M. Thomas: '''SGM symposium 61: Signals, switches, regulons and cascades: control of bacterial gene expression'''. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 81388 3 ©SGM 2002]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref9">[9] [http://mic.sgmjournals.org/content/147/12/3241/F4.expansion.html A. Khlebnikov, K. Datsenko, T. Skaug, B. Wanner and J. Keasling: '''Homogeneous expression of the P<sub>BAD</sub> promoter in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of the low-affinity high-capacity AraE transporter,''' Microbiology, 2001, (147): 3241–3247]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref10">[10] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10829079 Datsenko, KA, BL Wanner: '''One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products''', 2000 Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97(12):6640-5]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref11">[11] [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v434/n7037/full/nature03461.html Subhayu Basu, Yoram Gerchman, Cynthia H. Collins, Frances H. Arnold & Ron Weiss: '''A synthetic multicellular system for programmed pattern formation''', Nature 2005, 434: 1130-11342]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref12">[12] [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/182/3/805 Kristi A. Egland and E. P. Greenberg: '''Conversion of the Vibrio fischeri Transcriptional Activator, LuxR, to a Repressor''', Journal of Bacteriology, 2000, 182: 805-811]</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pymol: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref13">[13] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=49005 '''http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=49005''' NCBI Protein Structure summary, 18.10.11] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="Ref14">[14] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=52511 '''http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=52511''' NCBI Protein Structure summary, 18.10.11] | ||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/SectionEnd}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Team:ETH Zurich/Templates/HeaderNewEnd}} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:41, 29 October 2011

Contents |

Network Elements

SmoColi can be divided into different network elements: the major sub-networks being a sensor, a band-pass filter and a quorum sensing mechanism.

Cigarette smoke contains a lot of different toxic and carcinogenic components. In nature there are many sensors for such components, mostly to induce their degradation. One is the acetaldehyde system in aspergillus nidulans: the activator AlcR binds to its operator site if acetaldehyde is present [1]. Another one is the xylene sensing system in Pseudomonas putida [2] working as an activator. Since our system is constructed in a modular fashion an can be coupled with any sensor, an arabinose sensing system was established as a proof of principle.

We combined a smoke-sensitive band-pass filter with GFP output with a quorum-sensing based mechanism alarming the user at high smoke levels by expressing RFP.

Acetaldehyde Sensor

Where it comes from...

In Aspergillus nidulans, the alcR gene encodes a regulatory protein which activates the expression of the ethanol utilization (alc) pathway if the co-inducer acetaldehyde is present. Ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde by the alcohol dehydrogenase and further metabolized to acetate by the aldehyde dehydrogenase. Both genes alcA and aldA are regulated by AlcR. AlcR also regulates its own expression by autoactivation [1].

The AlcR DNA binding domain contains a zinc bi-nuclear cluster, which can bind either to symmetric and asymmetric sites with same affinity. In contrast to other members of the Zn2Cys6, the DNA binding domain is stretch of 16 amino acid residues between the third and fourth cysteine. AlcR binds as a monomer, but 2 proteins can bind to inverted repeats in a noncooperative manner. Additional DNA sequences upstream of the zinc cluster were identified to be responsible for high-affinity binding, [4].

How we used it

Because fungal activators normally do not work in E. coli, the system was modified to work as a bacterial repressor. The mechanism of how AlcR activates transcription is not completely known, which makes the process of redesigning it very challenging. A second challenge is the different codon usage in Apergillus nidulans and E. coli. The codon adaptation index (CAI) of Aspergillus nidulans AlcR is 0.7 in E. coli, especially at the beginning of the gene a few very rare codons are present. To get a fully E. coli-optimized gene, we ordered the gene codon-optimized. To get a partly codon-optimized version, we exchanged the rare codons at the beginning of the Aspergillus nidulans protein with PCR.

For a redesigned bacterial PAlc promoter, natural operator sites of AlcR from Aspergillus nidulans were placed between the -10 and -35 region of a constitutive E.coli promoter. Two versions of the synthetic promoter were implemented, one with direct-repeat targets and one with inverted [1]. The idea is that in the presence of acetaldehyde, AlcR will bind to the operon and block the binding of the RNA polymerase. This only works if the mechanism of AlcR transcriptional activation is based on acetaldehyde induced DNA binding and does not just involve conformational changes. When implementing the SmoColi genetic network, an additional inverter (TetR) is added in front of the bandpass, so that the acetaldehyde signal is passed into the bandpass in a positive way. Thus the AlcR promoter (PAlc) is cloned in front of the TetR repressor to introduce the bandpass.

Acetaldehyde is reduced by the native E. coli enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase, generating a concentration gradient in our tube. At the position with the required concentration of acetaldehyde for the bandpass-filter, GFP is expressed, at all other positions it is repressed, resulting in a single GFP band. By tuning the input of acetaldehyde in the tube, we get the GFP band at different positions. Thus, with constantly increasing acetaldehyde concentration, we get a moving band from one side to the other side of the channel. Finally,if the acetaldehyde concentration exceeds a certain threshold, the whole channel turns red, due to the quorum-sensing based RFP expression.

Xylene Sensor

Where it comes from...

The xylR gene in Pseudomonas putida encodes a 566 aa regulatory protein that activates the degradation of toluene and xylene. In P. putida the complete upper Tol pathway is under the control of the toluene-responsive promoter PU. In the presence of xylene, XylR hexamerically binds to PU promoter and activates it [5]. This activates expression of the xylene degradation cassette xylC-xylM-xylA-xylB-xylN, where xylC encodes for the benzaldehyde dehydrogenase, xylM and xylA for subunits of the xylene oxygenase and xylB for benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase [6]. XlyN is not required for the degradation of xylene, but it is part of the whole transcriptional unit. The DNA binding of XylR occurs at a 40 bp upstream activating sequence (UAS) located 150 bp upstream from the transcriptional start site of the σ54 PU promoter. DNA looping between the UAS and the -12/-24 motifs of the σ54-RNAP facilitates the activation of the holoenzyme by XylR [7].

How we used it

Xylene is not degraded naturally by E. coli. To generate a concentration gradient of xylene we engineered its degradation in SmoColi by including the upper Tol pathway. XylR is a prokaryotic enhancer binding protein, thus is completely functional in E. coli. As an input into the SmoColi system, LacIM1 and CI are put under the control of the PU promoter, enhancing their expression in the presence of xylene.

Arabinose Sensor

Where it comes from...

The AraC regulatory protein is a activator of the genes for the araBAD, the araE and the araFGH operon in E.coli. araB, araA and araD encode for the metabolic enzymes which degrade L-Arabinose to D-xylulose-5-phosphate. In absence of arabinose AraC does bind to two DNA site separated over 200 bp from each other (I1 and O2 of the PBAD promoter) [8]. By dimer formation of the two DNA bound AraC molecules the DNA is looped and transcription blocked. Binding of arabinose leads to binding of arabinose to I1 and I2, I2 bound AraC directly interacts with the RNA polymerase and activates it. araF, araG and araH and araE encode for proteins needed for uptake of arabinose. If some arabinose enters the cell, the uptake of arabinose is activated leading and more and more arabinose entering the cell. This positive feedback loop leads to an all or nothing response of arabinose in the cells.

How we used it

To show that our system can be activated by different signals, we introduced a arabinose sensor. Due to the fact that AraC s well established in contract AlcR and XlyR, the arabinose system can be seen as proof of principle for the bandpass and the alarm system for our smoke sensors. The LacIM1 and the CI regulators were under the control of the PBAD promoter, enhancing their expression in the presence of arabinose and the absence of glucose. The all or nothing response of the arabinose system makes the natural system unusable for our bandpass, because we need an intermediate input signal. In order that we can still use the arabinose system we use the BW27783 (BW25113 DE(araFGH) Φ(∆araEp) (PCP8-araE)) E.coli strain [9]. This strain has a knock-out of the araBAD (degradation), araFGH (low capacity, high affinity transporter) and the promoter of the araE gene (high capacity, low affinity transporter) has been exchanged from PBAD to PCP8, which is a constitutive promoter. The elimination of the positive feedback loop within this strains leads to a titratable response on arabinose, allowingintermediate input concentrations for the bandpass filter. By inactivation of the kanamycin casette, we created the BW27783 from the BW27749, which was provided to us by Khlebnikov et al. (Done according to the method of: [10])

Bandpass

Where it comes from...

In 2005 Ron Weiss et al. constructed the first band-pass filter device in synthetic biology. This was done by using the combination of a high-pass and a low-pass filter. An input signal is transmitted by cell to cell communication while the signal processing is done using an intracellular feed-forward loop. Filters are created by using different transcriptional regulator proteins with different repression efficiencies and binding affinities for corresponding promoters.

How we used it

We used his pioneering network design as a basis in the planning process for our band-pass filter implementation [11]. Instead of cell-cell communication via AHL for the input signal, we included our different smoke detectors which detect small volatile molecules like acetaldeyhde, xylene or arabinose.

Inverter

Where it comes from...

An inverter is a part which converts a repressor signal into an activator signal, or vise versa. For SmoColi we used TetR as an inverter. TetR binds and blocks the TetR promoter (PTet, [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0040 BBa_R0040]).

How we used it

When the inverter is not present, the band does not appear because the activation threshold of the high pass filter is at a higher value than the repression threshold of the low pass filter, thus there is no region where both branches produce an output signal. If the input signal (a repressor) is inverted we get again a nice bandpass filter. In our circuit the inverter is only needed for AlcR, for AraC and XylR the input signal is correct (they are already activators).

Quorum Sensing of the Alarm system

Where it comes from...

The luminescence operon in Vibrio fischeri is regulated by the transcriptional activator (LuxR). The lux box is a 20 bp inverted repeat sequence at a position centered 42.5 bases upstream of the transcriptional start. LuxR binds to the lux box in presents of AHL and enhance its expression. LuxR is needed to activate the σ70 RNA Polymerase. The Vibrio fischeri lux operon consists of seven genes, the first one is luxI. The luxI gene encodes for the enzyme for AHL synthesis. The autoinducer AHL is secreted by the cells to coordinate gene expression based on the local density of the bacterial population. Furthermore transcription of luciferase in the lux operon is induced, leading to bioluminescence.

How we used it

For our system we used a promoter which is repressed by luxR! ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0061 BBa_R0061]) It was designed by placing the lux box between and partially overlapping the consensus -35 and -10 site of an artificial lacZ promoter. In the presence of AHL, LuxR binds to the lux box and inhibits binding of the RNA Polymerase. [12]

References

[1] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2834622 R. Locklngton, C. Scazzocchio, D. Sequeval, M. Mathieu, B. Felenbok: Regulation of alcR, the positive regulatory gene of the ethanol utilization regulon of Aspergillus nidulans, Mol Microbiol., 1987, 1: 275-81]

[2] [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/64/2/748 Sven Panke, Juan M. Sánchez-Romero, and Víctor de Lorenzo: Engineering of Quasi-Natural Pseudomonas putida Strains for Toluene Metabolism through an ortho-Cleavage Degradation Pathway, Appl Environ Microbiol, 1998, 64: 748-751]

[3] [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/64/6/2032 Sven Panke, Bernard Witholt, Andreas Schmid, and Marcel G. Wubbolts: Towards a Biocatalyst for (S)-Styrene Oxide Production: Characterization of the Styrene Degradation Pathway of Pseudomonas sp. Strain VLB120, Appl Environ Microbiol, 1998, 64: 2032-2043]

[4] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9182587 Lenouvel F, Nikolaev I, Felenbok B.: In vitro recognition of specific DNA targets by AlcR, a zinc binuclear cluster activator different from the other proteins of this class, J Biol Chem. 1997, 272(24):15521-6.]

[5] [http://www.springerlink.com/content/r65l105rg21t1l73/ Manabu Gomada, Sachiye Inouye, Hiromasa Imaishi, Atsushi Nakazawa and Teruko Nakazawa: Analysis of an upstream regulatory sequence required for activation of the regulatory gene xylS in xylene metabolism directed by the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida, Molecular and General Genetics MGG, 1992, 233:419-426]

[6] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC210316/ S Harayama, M Rekik, M Wubbolts, K Rose, R A Leppik, and K N Timmis: Characterization of five genes in the upper-pathway operon of TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida and identification of the gene products, 1989, 171(9): 5048–5055]

[7] [http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/31/23/6926.full Marc Valls and Víctor de Lorenzo: Transient XylR binding to the UAS of the Pseudomonas putida σ54 promoter Pu revealed with high intensity UV footprinting in vivo, Nucl. Acids Res., 2003, 31 (23): 6926-6934]

[8] [http://gene.bio.jhu.edu/Ourspdf/108.pdf D. A. Hodgson, C. M. Thomas: SGM symposium 61: Signals, switches, regulons and cascades: control of bacterial gene expression. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 81388 3 ©SGM 2002]

[9] [http://mic.sgmjournals.org/content/147/12/3241/F4.expansion.html A. Khlebnikov, K. Datsenko, T. Skaug, B. Wanner and J. Keasling: Homogeneous expression of the PBAD promoter in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of the low-affinity high-capacity AraE transporter, Microbiology, 2001, (147): 3241–3247]

[10] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10829079 Datsenko, KA, BL Wanner: One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products, 2000 Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97(12):6640-5]

[11] [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v434/n7037/full/nature03461.html Subhayu Basu, Yoram Gerchman, Cynthia H. Collins, Frances H. Arnold & Ron Weiss: A synthetic multicellular system for programmed pattern formation, Nature 2005, 434: 1130-11342]

[12] [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/182/3/805 Kristi A. Egland and E. P. Greenberg: Conversion of the Vibrio fischeri Transcriptional Activator, LuxR, to a Repressor, Journal of Bacteriology, 2000, 182: 805-811]

Pymol:

[13] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=49005 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=49005 NCBI Protein Structure summary, 18.10.11]

[14] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=52511 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi?uid=52511 NCBI Protein Structure summary, 18.10.11]

"

"