Team:Paris Bettencourt/HumanPractice/wikiAnalysis

From 2011.igem.org

Human Practice

Synthesis and analysis of collaborative engagement within the iGEM community

Introduction

Much like in the early times of Biotechnology scientists gathered and set for themselves some basic standards and practices on both ethical and pragmatic issues I believe that it is time we, iGEMers, do the same. As future researchers, we are entitled to have our word on how the field of synthetic biology (as well as the iGEM competition) ought to look like. Did you know that the President Obama asked last year for a report on bioethical issues regarding Synthetic Biology? The report came out in December 2010 and included a set of recommendations that the discussion panel deemed necessary. Good. Better yet: why not produce a more down-to-earth proposal on synthetic biology ?

As an interesting turn of fate 2012 happens to be the year in which both French and US Presidential elections are happening (and 2013 for the German ones), what if we could produce a unified document that could potentially change the face of how Science is done? Ambitious? Most probably BUT if we co-operate at a European -and even worldwide- level such an aim is completely attainable. The first thing is to get the frame of analysis, have clear steps to follow if coordination is to happen.

Please find the outline we propose for the co-operative project for an iGEM centered proposal on synthetic biology.

The more we are, the more questions we can tackle! Everybody is welcomed.

Objectives

- Create a full list of teams and their respective Human Practice projects

- Identify societal issues mostly addressed by iGEM teams

- Propose a comprehensive review on synthetic biology from the iGEM point of view

- Analyze content and create debates within our team, Europe and iGEM community

Step 1: Scanning of the wiki

We dedicated a good deal of time just to actually go into each wikis of each years since 2007 until 2011 and found what were the themes tackled by the teams. A priori, we told ourselves that obviously teams having a clear human practice tab were to be considered but as in the past iGEM competition it was not mandatory to include such discussion we thought that people might have included it within a more general discussion and this is why we read all of them. Every time there was a discussion about bio-safety/bio-security, ethics or any kind of reflexion revolving around synthetic biology up to the application of the project was taken into account. The primary raw data was huge, but we already had quite an overview of what had been said. This is where we agreed between us to discard discussion on applications of a project since most teams where mentioning it. Second, we created six convenient categories that are as follows:

- Public education

- This includes bringing to the public (defined as other iGEM teams, scientists or the general public) a presentation of what is synthetic biology (SB) or the specific iGEM project may it be in the form of a forum, a conference or classes given to students.

- Public perception

- This includes getting to know the opinion or the preconception of what is SB, genetic modifications of organisms and any relevant pieces of information about their knowledge in biology/modelling/engineering. We also included in that part the social and political framework in which iGEM evolves.

- Patents and licenses

- This is a rather specific discussion or questioning about laws, patenting regulations and other legal concerns.

- DIY bio

- The Do It Yourself (DIY) movement is at the cross-section of many societal and scientific debates therefore it is a section in and of itself.

- Ethics

- This is the most vague section as it includes bio-safety, bio-security issues as well as questioning about application and societal implications of iGEM and biology at large. As a matter of fact any thorough investigations and questioning revolving around SB was included here.

- iGEM tool development

- Some teams decided to give back to the SB's community in another form than BioBricks, some of them developed "how-to" guides and others software programs.

Analysis of Data Scanned

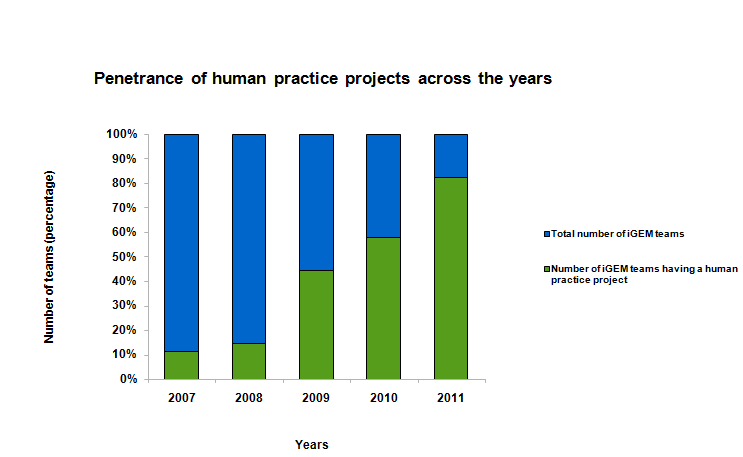

This way of regrouping common questions, common practices mentioned by the past teams allows for some basic statistical analysis. What we present here is mostly for descriptive purposes. The first trend that we observe is an obvious augmentation of human practice (HP) projects, both in terms of absolute numbers and relatively to the number of iGEM projects, over the years.

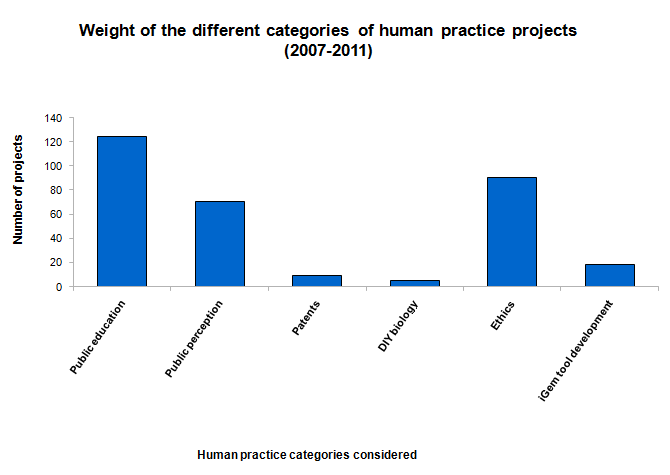

Second, we have this other simple bar graph that is an overview of the data obtained from the scan. It gives the relative amount of each kind of category. Interestingly, "Public education" has been the most widely discussed theme. Right after comes "Ethics" and "Public Perception". The three remaining themes account for the rest. It must be noted that we might at some point considered two different themes for a single team if their projects covered them so this makes a greater total number of themes than human practice projects per se.

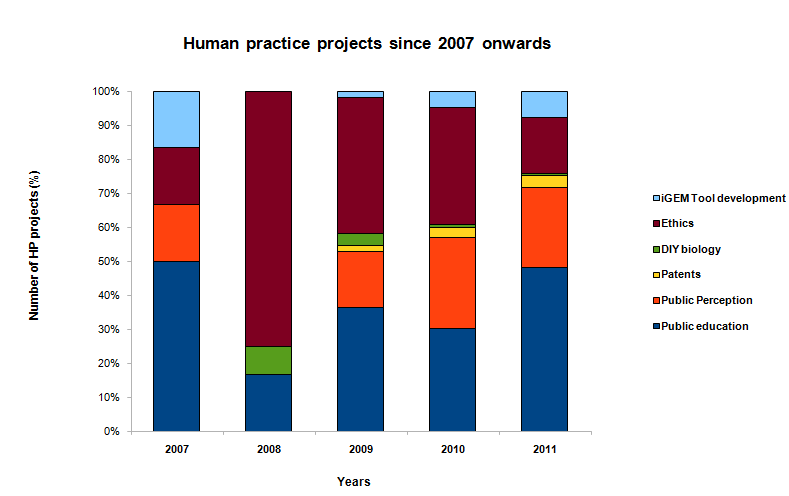

The graph below shows the percentage of each category of human practice project in each year of the iGEM competition. As observed, a greater number of teams that worked on human practice project in the beginning (2007;deep blue bands) focused on educating the public on the new field of synthetic biology. This has however decreased recently until 2011 since synthetic biology is growing in the community and the awareness is increasing, however since as of 2011 obtaining a gold medal includes a HP component it may have been an easy way to fulfil this criterion. Now that synthetic biology has become known to the public, the next hurdle is to look at the perception of the public (orange colour) on the field and this attributes to why an increase in human practice projects centred on public perception is observed in recent iGEM human practice projects. Secondly, Patents have become a great issue in synthetic biology as the idea is to create a standardised and reusable open source parts. The issue of patents in an iGEM project discovery and synthetic biology in general has called for an increase in the number of human practise projects addressing this recently (yellow bands). Ethical concerns (pink colour) were raised after the first iGEM competition (2007) on the potential dangers of synthetic biology and this called for a greater number of teams to focus on it in the next year (2008) as shown on the graph. Ethics still remains a major concern of synthetic biology and has since been addressed by the next generations of iGEM teams (2009-2011) although not as in the second iGEM competition. There were quite a low number of Do It Yourself biology (DIY) (green colour) issues addressed by the iGEM teams and this trend was also observed in teams that tried to develop tools (sea blue) (software, manual guides etc.). Some of the trends observed can also be attributed to the increase in diversity of the human practice projects as more teams tend to address different issues of synthetic biology in their projects.

Analysis of the Grenoble Video

The team from Grenoble made a video of a debate on synthetic biology that they sent to us as part of our Human practice project. They read the cooperative project proposal and decided to focus on a more ethical point of view. This kind of video provides a unique insight into what non-SBist think of the field.

The way they created the discussion allows people to express themselves and also to stir up substantive issues together. From their video, we highlighted three major issues: firstly, what means synthetic biology and what are the thoughts in terms of dream and fable? Secondly, what could be the main ethical issues? And finally how the future of such a field could take shape?

In the assembly, we saw two kind of personalities: on the one hand those that set out the idea of a technological tool that has practical applications and which is dedicated to commercial use. On the other hand people looking for any convincing arguments on the usefulness of SB. It clearly appears here that these people ask for more clarifications from scientists and companies. One of the fable behind could be the will of the synthetic biology cosmos to hide the truth in order to avoid any mass panic, as it happened with GMOs in France.

From the ethical point of view, two notions are underlined: the first of which is the scientists' responsibilities. Is the field too young insomuch, we scientists, fail analyzing it by taking a step back? Do we have enough credibility (And who would decide anyways? Politics, firms or scientists?)?

The last issue that was raised during the debate was: if there are commercial interests, how to avoid propagation of GMOs? Any scientist really has to dwell upon notions of capacity to live outside the lab, control and analysis of external factors. It is true, for instance, that if a commercial synthetic biological products was to be used by the general public there would be a clear concern of proper usage and proper recycling. This point allows me to dress up the second notion which is: do we have to put one's head on the block and what are the risks?

The final point raised was: we (as scientists) chose to work on synthetic biology because we have a lot of expectations but what about a renovation of the SB movement? Or should it continue as it is? And who would decide for us?

We find that, in the end, their debate revolved around the essence of SB whether it is a tool or a proper scientific field. This question brings about all the issues of decision processes and risks versus benefits assessment.

Step 2: Synthesize information and spark debates

Once the data retrieved and some information obtained on the nature of the themes and some knowledge about the questions treated we started to get interested in the patents matter. We decided not to treat ethics any further since we had the Grenoble debate video. The theme patents has been treated a few times only which is surprising since it seems to be a crucial theme for the good progress of iGEM projects in an open-source manner. It must be noted that the following text may not represent the profound opinion and beliefs of all the members of the team, however it created a sort of consensus when we debated. The debates were hold on a non-official basis the whole team participated. By no means this is a complete overview of the matter but it brings together the thought and information we had so far. This is obviously an ongoing debate.

On the matter of patents and patentability: basics

It ought to be mentioned that there is no need for an extensive survey of the literature to get a grasp of what the issue revolves around. Conceptually, it is mostly an opposition of private versus public good or reward versus exclusivity. Here, I present a view that is clearly from the narrow point of view of students in research and participants in the iGEM competition.

The process in and of itself had been created to reward an inventor by allowing him exclusive economic benefits for usually twenty years. The European criterion is as follows:

Art. 52(1): ” European patents are granted for inventions that are new, involve an inventive step and are susceptible of industrial application. An invention can belong to any field of technology » 1

This is quite vague and probably inadequate as we will see later. From my understanding, in regards to patentability of the living, treatment methods on animals and humans are not patentable while the molecules used are. Naturally occurring organisms are also excluded. However, and this is where it is most relevant to us is the point about microorganisms:

Guid. C-IV, 4.7 : The exclusion does not apply to microbiological processes or the products of such processes. In general, biotechnological inventions are also patentable if they concern biological material that is isolated from its natural environment or produced by means of a technical process, even if it previously occurred in nature.1

Our experience during the competition has been one of open-source: many researcher have kindly shared their strains and their technical knowledge when applicable, most notably the authors of the article we are basing our study on. To be added is the offer of the “push-on push-off” system put together by the PKU team. “Why can't it always be this way?”, we asked ourselves naively. The immediate answer that was given by some non-biologists was that we were working at the fundamental level, with no real big money in play. In effect, bearing in mind Berkeley 2007's example, the questions of patents poses itself, at our level at least, if a clear application is the outcome of an iGEM project. That lead us to think about this issue, although we did not hit a dead end by confronting patented material. And the first step we took was to analyse was being said both in the Obama Report on SB and what had previous iGEM teams had said

Analyzing the debate

Analysis of Obama's report point of view

The [http://bioethics.gov/cms/synthetic-biology-report Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues] in their « analysis and recommendations » section identify that indeed intellectual property and sharing of scientific knowledge are crucial issues in synthetic biology. They are however, may be due to divergent point of views in the people involved in the debate, stating that they are unable to solve the issue and they cannot even offer insight into what needs to be changed to achieve synthetic biology's promises. This is understandable in some ways since in America free enterprise, one of the pillars of society, cannot be touched upon even if it profits only to the fewest (i.e. the largest industries) and they predict a lot of revenues could be made through synthetic biology if 1 trillion dollars had been generated just in the pharmaceutical industry for “lifestyle” product. Like most ethics debate, they just recognize that they are questions raised but refuse to solve them but encourage transparency and hope matters will evolve by themselves. Just like Virginia 2011 pointed out, the presidential commission still believes that it is up to governments and public agencies to finance 'risky research' or non-profitable ones (such as tropical diseases which are virtually absent in Northern industrialized countries but where the pharmaceutical market is).

Analysis of the iGEMer's point of view

We see that we cannot trust the U.S presidential commission to address correctly the patents issue and it brings about absurdity most notably outlined by MIT 2010. Since we already are in this sort of market-free environment and asked to think critically let's turn to the analysis and reflexion previous iGEM teams did. While some do not bring anything significant, a couple teams stand out. Freiburg Software 2010 compares the rise of synthetic biology to the change of company controlled source code into open source codes and they propose that if everything was to go in the public domain - and they should, states Tianjin 2010, because it belongs to society - then companies could survive by offering long term services and expertise in specific domains. Otherwise, we find ourselves (the students) in a difficult choice: a potentially exciting and new design/system but that has to be paid for or not doing it at all. Conceptually, from the iGEM's point of view the real strain is between accessibility and exclusivity.

How can we bridge the concepts of sharing and open-source with the justifiable desire to reward real innovators? Insight on how to solve this question is offered by uOttawa 2010 by achieving what they call a "reach through licensing agreement" whereby researchers pay little or nothing for using patented material and if a new innovation is made then the original patent holder can have a share. This idea is very interesting since it frees fundamental research from patentability issues, problem could arise when it comes to sharing. It is imaginable that legal minima could be set in order to solve future problems. They argue that it shifts the legal issues from researchers to those who actually want to make profit.

This also brings us to what seems to be a confusion, it often seems that innovators are impersonated as single researchers who deserves in the theory financial gains for their discovery whereas problems are often described in a setting where it is an already wealthy company which files patents and make a whole vending strategy around them. That is to say there is always an often unrecognized two speeds system whereby one is rewarded but the other profits abusively from it.

A first idea that could allow the bridging of concepts is a compromise that would ease up the research of future iGEM teams which has been put forward by UQ_Australia 2011. They feel that making an overarching license for all competitors as long the patented sequences are used uniquely within this framework. In this context, patent holders (most likely multinationals) would become sponsors but there are chances that most will refuse based on mistrust and lack of control; yet it could be a good start for iGEM's sake. Furthermore, this does not apply to the larger SB community.

It appears that another model that would satisfy our needs as iGEMers is Virginia 2011's since it is based on public beneficence. The less extreme version of the model would be a direct funding reward model whereby the governments finances specific research and development if the inventor decides to put his invention in the public domain. This team goes even as far as suggesting that a total socialization could be the key to the problem. In practice, there would be no more patents but financial rewards for researchers in the form of research funding and/or percentage on the sales generated by the invention. This could ironically also allow free market -liberal approach- models to function since no patents could open the door to competition, secrecy or trade strategies thereby lowering prices and improving accessibility to lower classes and to non-industrialized countries. Albeit an extreme model, it would fulfil most of the goals of synthetic biology. For iGEMers, this would also be a guaranteed protection against troll patents.

Sparking debates within the team

We also would like to present our own discussion, it was interesting to discover that very different opinions are held even within a single iGEM team. For example, for some of us genomes should not be patented whatever the organisms, a thought that may not be shared by everyone in the team.

Research first!

That is the main point I want to focus on, indeed as future researcher we are maybe going to be confronted with patent issues. I see no reason why any form of retention should come up in research even if patented material is used. It seems that usually University researchers do not encounter such difficulty 4, however in a preventive manner it should made explicit in biotechnology patents that every bit of information concerning the “invention” should be made public, freely available and threat of going to court forbidden. This is just extending the Synthetic Biology principles already exposed by Jimmy Huan of the 2008 UCSF team but applying them to the whole Living and all genomes. This open source approach in essence makes a common database of genes accessible to all researchers worldwide.

Noteworthy: I am not condemning patenting, it is a perfect way to reward an inventor (a finder more like in the context of biotechnology) for its ingenuity and hard work. However, it must not impinge on further research so, in a way similar to the BioBrick legal situation, all DNA must be open-sourced even though a particular application may be patented. In my opinion, this would be putting into practice one of the ideals of synthetic biology.

A possible solution that I foresee is to be able to patent only the final product of the genetic circuit may it be a function, a medicinal molecule etc. if and only if it has the previous requirements of general patentability.

Pragmatic approach needed

Not even considering religious issues, how can one really claim to make someting new if it is just “discovering” something that existed? The term discovering is used sarcastically since on a conceptual level even if one made a modified antibiotic or whatever he still started with the existing genetic sequence and worked in such a way that one induced a conformational change in a protein that so happened to be beneficial. This point is very debatable but nonetheless patents are useful to get the credit for one's research and efforts. Taking an example of the possible absurdity of the application of patents and the distribution thereof is given by the European Office of Patents 3 : there exist a practice that consists of collecting, characterizing and then use exotic plants to create novel drugs even though the properties of it were known for centuries. Bio-piracy 6, as it is called, aims at patenting genes that have an obvious function but have not yet been characterized and hence are patentable. This practice is unacceptable because the population that were cultivating it might just have to pay the pharmaceutical firm to get the exact same product. I believe that once again if genes were removed out of exclusivity then no problems would arise. The said firm would have to use fair techniques to compete against the local production: such as proposing cheaper drugs. In the envisaged solution (final product only equals possible patentability) only the final molecules would be patented under this conditional name: molecules "X, Y" coming from a "W" enhanced genetic circuit in microorganism "Z". Under this condition, no genes could be patented, the plant genome's or the respective sequenced part available without trade secret, research could ensue and the country could still naturally produce it's plant and use it in a traditional way may the economic incentive to do so be there.

Next steps

The most extreme opinions involve abolishing patents, some intermediate believe that the defintion must be changed and the practice must be different. May it be for visibility reasons, for acessibility or on moral grounds we seem to however all believe that the situation on patents must be changed. We agree that we iGEMers and researchers in SB should all have unlimited and free access to patented material at least for basic research. A clear next step would be to either team up with lawyers or investigate ourselves the precise laws regarding patents and propose to political institution the modifications that we deem necessary. To then fully accomplish all the objectives we would need to make the proposal visible (media, internet) for more weight and repeat the analysis for every aspect treated or not by previous iGEM teams and Obama's report.

Sources

1) European Guide For Patent Application [http://www.epo.org/applying/european/Guide-for-applicants.html]

2) Biotechnology in European patents - threat or promise? [http://www.epo.org/news-issues/issues/biotechnology.html]

3) India’s Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL): A powerful tool for patent examiners [http://www.epo.org/news-issues/issues/traditional.html]

4) Can patents deter innovation, the anticommons in biomedical research. M.A. Heller . Science 280. 1998 [http://www.sciencemag.org/content/280/5364/698.full?searchid=1&HITS=10&hits=10&resourcetype=HWCIT&maxtoshow=&RESULTFORMAT=&FIRSTINDEX=0&fulltext=michael%20heller]

5) Gene Patents, in From Birth to Death and Bench to clinic: The Hasting Center Bioethics Briefing Book for Journalists, Policymakers and Campaigns. R. Cook-Deegan [http://www.google.fr/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CCMQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.thehastingscenter.org%2FuploadedFiles%2FPublications%2FBriefing_Book%2Fgene%2520patents%2520chapter.pdf&rct=j&q=Gene%20Patents%2C%20in%20From%20Birth%20to%20Death%20and%20Bench%20to%20clinic%3A%20The%20Hasting%20Center%20Bioethics%20Briefing%20Book%20for%20Journalists%2C%20Policymakers%20and%20Campaigns&ei=rj12Tve0J6HW0QX9h82YCA&usg=AFQjCNHdE2ns1fmKhHj4A3J12dnjL25ZIA&cad=rja]

6) Biopiracy: The Legal Perspective. M.A. Gollin [http://www.actionbioscience.org/biodiversity/gollin.html]

"

"