Team:Paris Bettencourt/Project

From 2011.igem.org

Overview of the project

Mankind is only beginning to grasp the complexity of living organisms. New discoveries often challenge our understanding of life. We believe that synthetic biology can be used as a powerful and reliable tool to help us comprehend and characterize the phenomena we just encountered.

As an iGEM team, we decided to work on one of the most intriguing microbiological discovery of the last decade: the existence of nanotube communication routes in Bacillus subtilis!

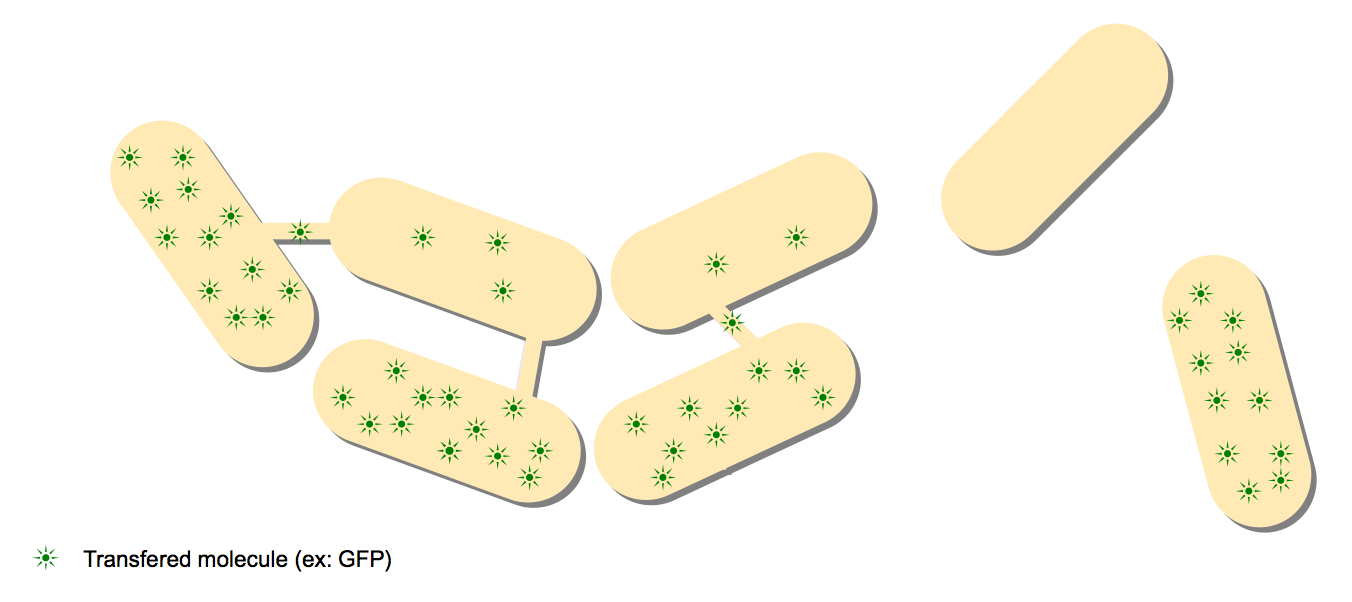

The recent discovery of nanotubes between individual Bacillus subtilis by Dubey and Ben-Yehuda spiked our interest. Through very detailed and advanced microscopy, they showed nanotubes forming between cells and that a wide range of proteins could pass through this communication channel (GFP, calcein, antibiotic resistance proteins, ...). They also showed signs of communication between B.subtilis and E.coli, two entirely different species. This counter-intuitive communication channel could very well have a tremendous impact on evolution, with two different species sharing proteins and even genetic material.

The Project

The existence of the nanotube network discovered by Dubey and Ben-Yehuda is still discussed. We wanted to use synthetic biology to provide new evidence supporting the existence of a new cell-to-cell communication in B.subtilis and between B.subtilis and E.coli. Thus, we want to characterize this communication as best as we can using carefully crafted genetic designs. We also aim at proposing new applications combining synthetic biology and the nanotubes network.

Each step of our project corresponds to a new level of understanding of the nanotube network inner mechanisms.

Modeling the transfer through the nanotubes

We wanted to see if the process of non-specific transfer through the nanotubes was possible in theory. In order to do so we designed two transfer models.

First we wanted to see if an active transfer was possible. Since the Dubey/Ben-Yehuda article shows that a wide range of molecules can pass through the tubes, we felt it was unlikely. We chose to investigate an alternative mechanism. Based on tension difference between the lipid membrane of two neighbouring cells, we propose a model that could justify the quick transfer through the nanotubes. We call it "assisted diffusion".

The detailed explanation for this assisted diffusion model is available here.

The results of this assisted diffusion model might not fully explain what was observed in the article. We therefore created a passive diffusion simulation to further investigate the possible explanations for the transfer. The results of this model can be found here.

Both these models were of tremendous help when we designed our construct. They showed us that it would be indeed very difficult to directly measure diffusion through the tubes since they suggest it might be a very fast process (taking less than a minute). We had to focus on other parameters to measure than diffusion time.

Preliminary experiments

We aimed at reproducing the observations made in the original paper. To this end, we re-did the antibiotic resistance and the GFP transfer experiments. We also introduced new hypotheses when it was required and came up with alternative explanations for the results observed.

Since we did not have access to an electronic microscopy facility, we were not able to reproduce the most striking pictures of the article. However, we were determined to obtain quantitative and reliable results with synthetic biology approach.

Characterization

The main goal of our project is to characterize the nanotubes. What passes through them? How efficient is the transfer through the nanotubes network? What are the typical reaction times in our systems? We tested if RNA, proteins of different sizes and/or metabolites can pass through and with what ease and rate. Our methodology is to pass different molecules so that we can characterize the transfer mechanism for a wide range of parameters. For that purpose, we engineered, using synthetic biology approaches, different designs built on this logic:

- An emitter cell produces a signal (RNA, protein etc.)

- This messenger passes through the nanotubes and into the receiver cell

- The receiver cell has specific promoters that activates an amplification system

- This amplification system in turn triggers a reporter mechanism we can measure (fluroescence, others)

Even though the inter-species (B.subtilis-E.coli) connection seems more difficult to reproduce, according to the Dubey/Ben-Yehuda paper, we decided to explore it along with the B.subtilis-B.subtilis connection. This was mainly motivated by the overwhelming number of Biobricks available for E.coli when compared to those available for B.subtilis.

An overview of these steps of the project is available here.

Modeling our designs

In order to predict the expected behaviour of our constructs and see what could be the key parameters of the experiments we created models of the genetic networks our designs. We saw which designs were the most likely to be successful and which ones would give us results more difficult to comprehend.

You can find more about the models of our designs here.

Results

We conducted numerous experiments during the summer to test the so-called nanotube transfer. We re-did the original experiments, characterized our parts and finally tried to test the nanotube transfer with our new designs.

These experiments were designed according to the results of our modeling, both for the genetic network and the transfer mechanism.

You can find more about our lab achievements here.

Summary of the article:

The article published by Dubey and Ben-Yehuda [1] in the journal Cell is the starting point of our project. In this paper, they show an extraordinary new form of communication between Bacillus subtilis cells and even exchanges with E. coli

The article in 5 bullet points (all of this happens on solid medium only):

- GFP and calcein, two molecules which cannot leave the cytoplasm, can be transferred to neighbouring cells in B.subtilis.

- A nanotube network can be observed through electronic microscopy between B.subtilis cells.

- GFP can be observed passing through these nanotubes.

- Antibiotic resistance can be transferred between B.subtilis cells or between B.subtilis and E.coli, both in a hereditary and a non-hereditary manner.

- Nanotubes connecting different species (B.subtilis, E.coli and S.aureus) have been oberved with electronic microscopy.

The starting point of this paper is the culture of two different strains of B.subtilis. One produces GFP, a fluorescent protein and the other does not. When grown close together on a solid medium, a transfer of fluorescence from the gfp+ towards the neighbouring gfp- cells was observed. Interestingly, this transfer was clearly linked to the distance between two different individuals.

To test if this transfer could be reproduced with smaller molecules, the Dubey/Ben-Yehuda team worked with calcein. Calcein is much smaller than GFP (623 Da to compare to 27kDa). Calcein can be used to label cells as it easily enters the cell but does not leave the cytoplasm afterwards. In addition calcein can be hydrolysed by B.subtilis, resulting in a strong fluorescence. Calcein-free cells growing on a solid medium near calcein-labeled cells exhibited the same behaviour as in the GFP experiment above. Non-fluorescent cells exhibited fluorescence and calcein-labeled cells were less fluorescent as time passed. Controls however showed that calcein+ cells kept a steady fluorescence and calcein- cells were not fluorescent.

These two experiments suggested that a close range cell-to-cell communication pathway exists in B.subtilis. The Dubey/Ben-Yehuda team investigated this discovery further using electronic microscopy.

The pictures support the existence of numerous nanotubes connecting cells. To ensure that these nanotubes could be a significant transfer mechanism, another GFP experiment was tried. Similar to the first one, two antibodies were added. One was an anti-GFP antibody, attaching to the GFP molecules. The other was a secondary antibody attaching to the first one and gold-conjugated. This way, individual GFP molecules could be tagged with the gold-conjugated antibody and followed by electronic microscopy. In this case, they observed GFP molecules moving in the nanotubes from one cell to another.

The images showed that nanotubes were between 30 and 130 nm wide and up to 1 µm long

The next step was to study antibiotic resistance transfer. Trying to see if non-hereditary (through resistance protein sharing) and hereditary (through plasmids) resistance to antibiotics could be passed through this nanotube network, they manipulated different strains of B.subtilis. We reproduced these experiments and some others related to antibiotic resistance and discussed this matter at length here.

Finally, encouraged by the results of these antibiotics experiments, the Dubey/Ben-Yehuda team took another round of fluorescent and electronic microscopy pictures, this time involving B.subtilis, E.coli and S.aureus. Nanotubes connected those different species, even though some are Gram-positive (B.subtilis and S.aureus) and the other is Gram-negative (E.coli)!

References

- Intercellular Nanotubes Mediate Bacterial Communication, Dubey and Ben-Yehuda, Cell, available here

"

"