Team:Edinburgh/Interview Analysis

From 2011.igem.org

Interview Analysis

During our interviews, a number of themes came up. Some related specifically to our biorefineries project, while others applied to synthetic biology more generally.

Contents |

Biosafety

Precautionary Principle

A number of interviewees mentioned the Precautionary Principle, which states that we should not do something unless we understand things well enough to know that it is safe. The Principle demands that anyone undertaking research show that it is not harmful.

Regulation

Some interviewees wanted to see greater regulation; for example by requiring stricter containment facilities for genetic engineering labs. There was a general acceptance of the need to strike a balance between regulation and allowing research to go forward, and one interviewee said that UK governments have been well-informed and generally set up the right level of regulation.

One of our interviewees took the view that it was best to be on the leading edge of research, as this would help us prepare for bioterrorism or bioaccident.

We wondered whether tough regulation would lead to research going abroad, but one of our interviewees suggested that in some areas the UK government has to take a stand that something isn't acceptable, and if the result is research going abroad then so be it.

Accidental release

The accidental release of organisms into the environment was a concern of several interviewees. One pointed out that humanity has a dismal record of releasing alien species into the environment, leading to drastic ecological damage.

Another said that, when an organism is used on an industrial scale, release is inevitable. This implies that we must ensure an organism is safe; we can't rely on containment working (but this is not a reason to be lax in our containment efforts!)

Risk assessments

The need for risk assessments was made clear by several interviewees. Of course, these already exist; our own project was subjected to a risk assessment.

Social justice

Who benefits?

Several interviewees were concerned that new technologies, including synthetic biology, would be used as tools for the rich to exploit the poor. "The rich" could mean either rich corporations, or rich nations.

Exploitation / sourcing

This was particularly relevant to our project, since a biorefinery would require large amounts of feedstock. While ideally such feedstock would be mere waste, some interviewees questioned the plausibility of this. We must avoid a situation where land is diverted from food production for the sake of producing crops that are turned into high fructose corn syrup or ethanol for the rich.

Sustainability

Interviewees from an environmentalist background were concerned that feedstock for a biorefinery be sustainably sourced. Some stressed that humanity is living beyond its means, and will soon be forced to reduce its levels of consumption.

Other ethical questions

Animal suffering

A couple of interviewees mentioned this as a specific concern. It is not relevant to projects involving bacteria, but in the future it will become easier to modify animals. Where this is for research, we must ensure that suffering is minimised, and if it is ever done for purely aesthetic reasons (e.g. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GloFish GloFish]) then we ought to ensure there is no suffering at all.

One interviewee pointed out that genetic modification of animals is strictly regulated in the UK.

Other disciplines

One interviewee pointed out that biologists are not trained ethicists, and emphasised the need for involvement of people of other fields. Another pointed out that "human practices" has always been a key part of the synthetic biology community - for example at conferences, it is always a major subject for discussion.

Democracy

Public engagement

Several interviewees stressed the need for open debate and public engagement. This is true at two levels: the level of society, where a broad scale debate must take place, but also the level of local communities, where biorefineries will be placed or crops will be grown.

There is a need for consultation, and projects must not go ahead without the consent of the people affected. Anyone likely to be affected by synthetic biology projects ought to be fully informed.

Media interaction

One interviewee criticised media reporting of GM foods. In general, the interviewees stressed the need for the public to be well-informed of what is going on; naturally this requires accurate reporting in the press.

Patents

Two interviewees mentioned gene patents as a potential problem. One was concerned about how patents are often used to prevent rival businesses from going ahead with their plans. Another mentioned the difficulties a small country has in dealing with patent issues, and mentioned the need for a unified approach in the European Union.

The limitations of technology

Many of the interviewees stressed that technology is not a panacea that will cure the world's problems. Other more fundamental solutions are needed, and these will involve changes in politics and society. One interviewee said that, while future technology may help deal with environmental damage already done, we cannot rely on it to forever fix our mistakes.

Positive vs. negative vs. those in between

Given the variety of the interviewees it followed that the responses were also varied both in content and opinion. Many interviewees hovered on the precautionary side, reminding us of the limitations of Synthetic Biology, while others were very enthusiastic and encouraging of our endeavours.

For instance, we explained our project to Eric Hoffman,a biotechnology policy officer with Friends of the Earth suggesting that it could be used to convert waste cellulose into many useful products such as food additives. He, whilst noting the merit of the science, asked whether it was an appropriate application: is the current application of recycling cellulose (i.e. composting) in need of replacing? Does our system offer more potential benefits than the natural one already in place? He mentioned how scientific research often produces novel innovations which people then try to apply to existing ‘problems’. He asked whether this was the correct way to create solutions or whether a more direct approach to tackling problems was necessary.

On the other hand, Nicolas Peyret, a market and investment analyst with Scottish Enterprise, was highly enthusiastic about our project. When asked about regulation he stated that balanced regulation was not just important to allow commercial enterprise to flourish but also to ensure bio-security was maintained. If regulation was too strict in one country and thus hindered the field from advancing then research would be moved elsewhere where it could advance. This could create compromising situations if this advanced research was used in a malicious way, i.e. bioterrorism. It seemed that in a number of interviews a need for a global regulatory body was made apparent.

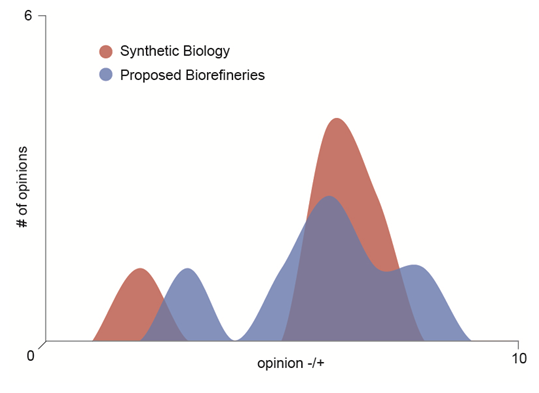

Overall, an air of cautious optimism was held, both toward our project and toward synthetic biology as a research field. We created an arbitrary graph (see fig p.1) to illustrate where we felt opinions lay.

Obviously, the scenario we presented was hypothetical and the questions we asked often generated discussion rather than found answers. The interviewees responded accordingly, offering only what they could without the necessary detail to make proper decisions. In all instances, however, it was decided that the drivers of synthetic biology needed to be altruistic and in order for that to happen an air of humility was of paramount importance. We must constantly question whether synthetic biology is an appropriate solution/innovation and if so, what are the wider implications an application of that knowledge would create? Are those implications worth the technological advance?

Upon reflection

So are biorefineries a feasible application of synthetic biology in society? At this stage it is difficult to tell.

When asked how his constituents would feel if a biorefinery was proposed to be built in his constituency Patrick Harvie, MSP, responded with more questions. He asked: how would the biorefinery look? How much space would it use? How much economic activity would it generate? Would it bring employment for the local population? And obviously, what kind of environmental impact would it have with regards to pollution, etc? These are questions that we had indeed thought about and had, to some extent, calculated; but not necessarily ones we had concrete answers to. However, if we consider current technologies in place that resemble biorefineries i.e. chemical plants, it isn’t hard to foresee a biorefinery development. In fact, there are already a number of them in existence is the United States.

Issues were also raised about the sourcing of biomass for feedstock. We had envisioned that the biorefinery could use cellulose-based waste as a feedstock (this could include paper-waste and perhaps other wood-based waste as well as agricultural waste) but it is possible that these waste sources would be insufficient to sustain a continual feedstock at present. And if waste wasn’t a sustainable feedstock how else could we create biomass? Using our currently proposed application i.e. producing foodstuffs, it seems counter-intuitive to devote acres of land to the production of biomass when they could instead be used to produce food.

Overall, we think it may be feasible for our proposed biorefinery to exist within society. However, that conclusion is dependent upon a restructuring of systems and legislation that would facilitate a biobased economy. Ultimately, only society can make the decision.

"

"