Team:DTU-Denmark/Project improving araBAD

From 2011.igem.org

Experiment: Improving araBAD

Contents |

The araBAD promoter (BBa_I0500)

In our project to control chiXR (one of the sRNAs) expression we used the arabinose promoter (PBAD) from the araBAD operon that is regulated by the AraC protein[3]. AraC can work both as a repressor and activator of PBAD. In the absence of arabinose, AraC represses transcription from PBAD while a conformational change turns it into an activator in the presence of arabinose. In addition, the promoter is subject to catabolite rerpession and is, thus, further repressed in the presence of glucose.

PBAD is a very frequently used promoter because of its extreme tightness. In the presence of glucose, this promoter triggers negligible amount of transcription which allows cloning of toxic genes downstream of it, however, it is also relatively weak even upon full induction preventing high level of expression which could be necessary, e.g. for protein purification. Even though the response of the PBAD promoter appears graded to inducer concentration at the population level[2][3], it has been demonstrated that this is not the case at the individual cell level.[1] An "all or nothing" behaviors with cells being either completely "OFF" or fully "ON" have been showed and only the fraction of OFF/ON cells is varying upon arabinose concentration modification. As a result only a subset of cells becomes induced with the arabinose. This can be very problematic when trying to express poorly soluble functions or when working at the single cell level. This "all or nothing" behavior stems from the arabinose transporters being also positively regulated by arabinose. Upon entry of a little bit of inducer, a feed forward loop sets in. The transporters are strongly upregulated as they bring more and more arabinose into the cell until the inducer is exhausted in the immediate vicinity of the cell and the systems turns off. To circumvent this pitfall, researchers have created the strains which are constitutively permissive for arabinose entry, thus, breaking the feed forward loop. Such approaches, however, necessitate the introduction of many mutations inside a strain and is, therefore, difficult to implement in other microbes except E. coli where the strains already exist[2][4]. Besides, if an intermediate level of induction is required for a system to be optimal, reproducibly adding the exact precise concentration of arabinose in the culture can be a significant hurdle.

We have approached the problem through another angle. If it is difficult to obtain reproducible results by changing the inducer concentration, why not try and change the promoter strength and systematically use a saturating amount of inducer? Our approach was, therefore, based on last year's iGEM DTU team work on Synthetic Promoter Libraries but applied to an inducible promoter. In the process we were also hoping to obtain stronger than wild-type, but arabinose regulated, promoters which could better match other induced systems like the Ptet promoter[6] or the propionate induced PprpB[7].

Approach

Since control of the system is essential to the applicability of our system we attempted to modify the dynamic range of the arabinose promoter ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I0500 BBa_I0500]) by two means:

- rationally designing the -10 and -35 sequences of the promoter region since both the -35 (CTGACG) and the -10 (TACTGT) of the arabinose promoter are far from the consensus (TTGACA and TATAAT respectively) thus potentially explaining its weakness.

- randomizing all nucleotides between the -10 and the -35 boxes as well as a few residues on each side thus creating Synthetic Promoter Library (SPL) similar to that described in SPL but without any modification to the natural -10 and -35 from BBa-I0500.

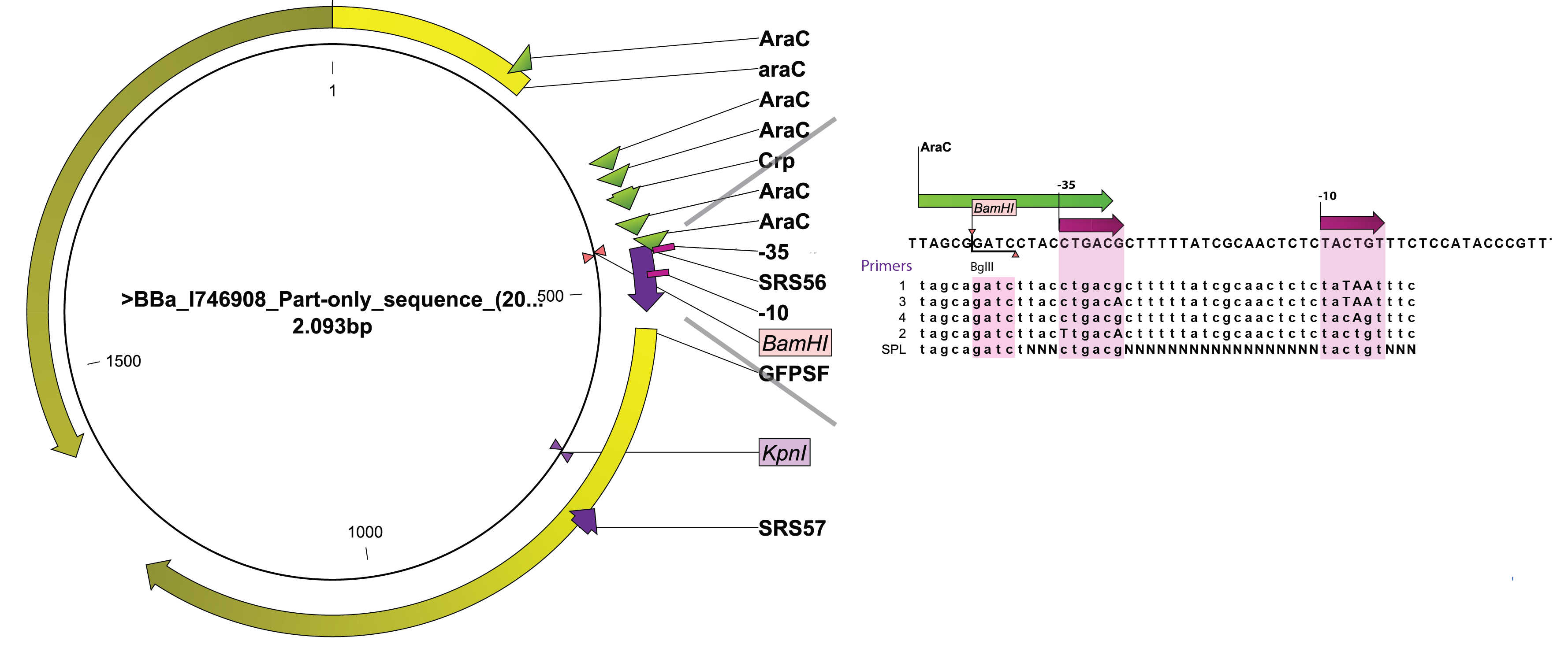

SPL require screening fo a relatively high number of colonies to obtain a representative idea of the promoter diversity generated. We therefore wanted to take advantage of the BioLector aparatus available on campus. Indeed, this highly parallel micro fermentor allows testing 24 colonies at a time with minimal human interference. As a consequence, we sought for an existing PBAD regulated GFP or RFP within the registry as their activity can be measured by our machine. We turned to [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746908 BBa_I746908] created by the Cambridge team in 2008. A rapid look through the sequence of BBa_I746908identified two unique restriction sites that could be used to levitate the existing wild-type promoter and replace it by engineered variants, BamHI, located immediately upstream of the -35 box and KpnI, within the GFP gene. A PCR primer (SRS57) was designed to anneal downstream of the KpnI and amplify the 3' end of GFP in conjunction with 5 different primers designed to overlap the arabinose promoter and introduce defined changes in the -10 and/or -35 box (SRS56-1, -2, -3, -4) while SRS56-SPL created a bank of promoters with highly variable spacer sequences (see Figure 1). SRS56 also features a BglII site in place of the natural BamHI site so that proper mutants could be easily screened out after ligation and transformation.

Detailed description of the experiments, including information on primers used, can be found in notebook.

Results

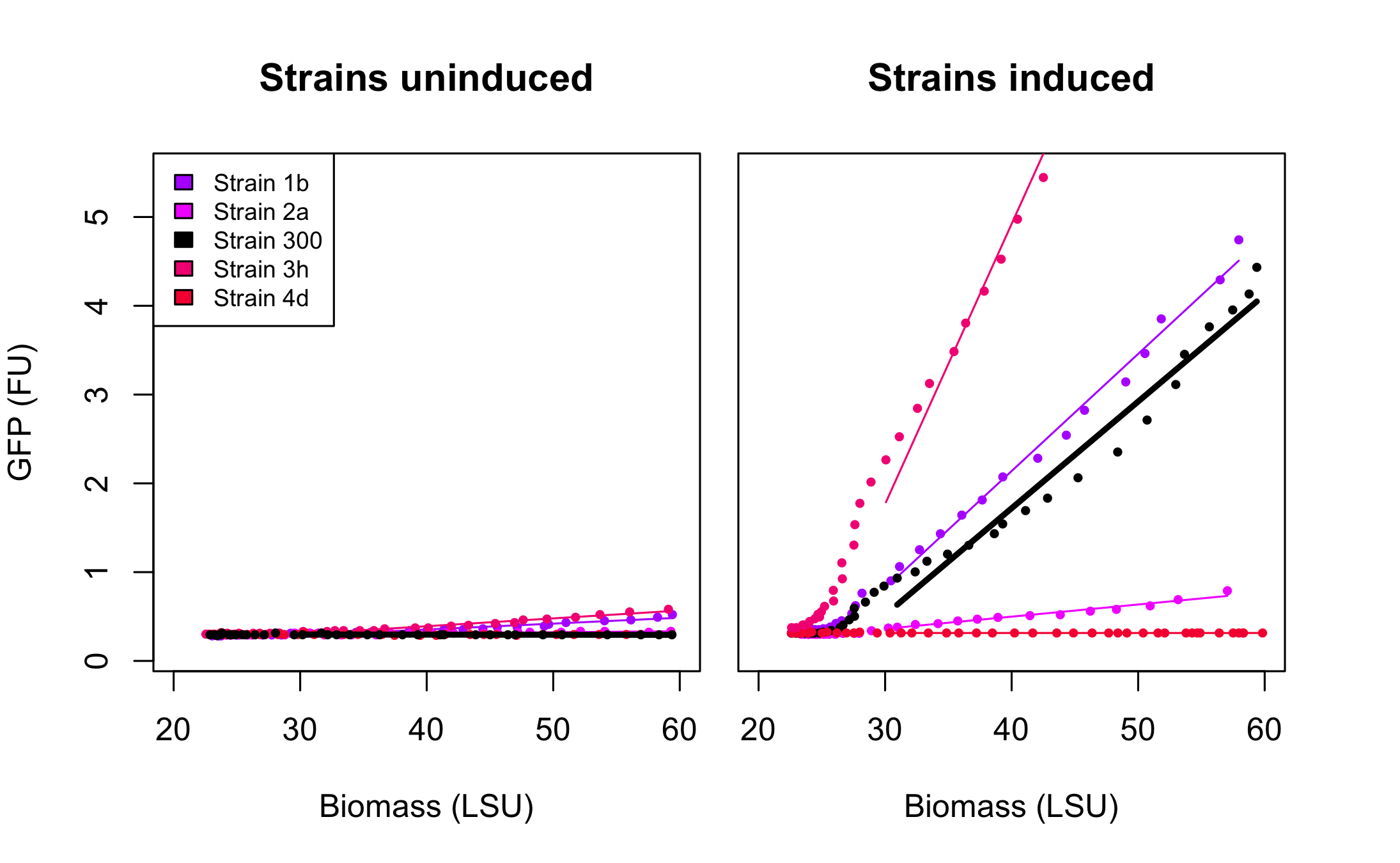

As seen on the accompanying figure, SRS56-1 aimed at bringing the -10 box to consensus (TACTGT-->TATAAT), -2 brought the -35 box to consensus (CTGACG-->TTGACA), while -3 and -4 modified both -35 and -10 boxes in order to bring them closer to consensus. Several correct clones were found for each rationally modified PBAD and roughly analysed in a fluorometer. They all displayed similar fluorescence levels induced or not and only 1 of each type was kept for further analysis in the biolector in order to make room for as many PBAD-SPL clones as possible. After verification of BamHI resistance, 18 randomly chosen clones from the SPL were analysed in the BioLector. All 4 rationally designed (in strains called 1b, 2a, 3h, 4d, the number refers to the primer that was used for their construction) and 18 SPL-changed arabinose promoters (in strains called SPL-1 up to SPL-24) fused to GFP were tested under induction with arabinose at concentration 0.2% and compared to non-induced state. The original [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746908 BBa_I746908] BioBrick was also included and named strain 300. In all the figures the GFP expression and the biomass concentration are expressed in fluorescence unit (FU) and light scattering unit (LSU) respectively.

Figure 3 presents the characterization for the rationally designed arabinose promoters. When uninduced (left part of the figure) the background GFP expression level for strains 1b and 3h is slightly above the background in original promoter (black line) which indicates that these promoters are less tight. In case of strains 2a and 4d the basal expression level is comparable to the original promoter. From the right part of the figure we can see that the induction didn't influence expression in strain 4d which implies that unknown mutations abolished arabinose regulation in that promoter. In the case of strain 2a induction is maintained, however its level is much lower than that of original promoter. The mutations increased the promoter strength in strain 1b and 3h when compared to strain 300. These results seem to point, as could be expected, towards the -10 playing a more important role in strength determination than the -35. The -35 apparently requiring to be "bad" for the stimulatory effect of AraC bound to arabinose to be optimal.

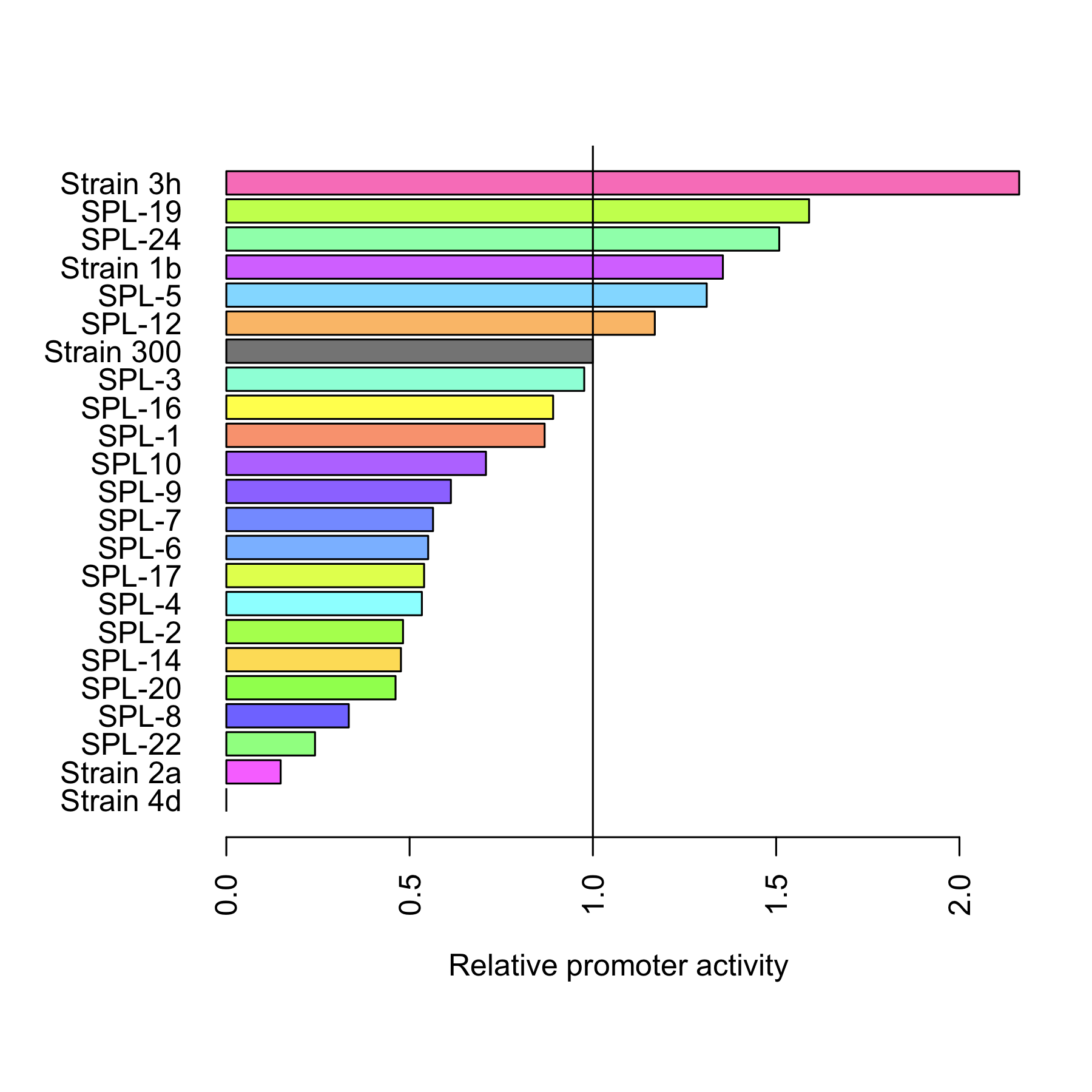

Figure 4 presents the characterization for the arabinose promoters changed using SPL. At the uninduced state (left part of the figure) the basal expression of all promoters is at the same level as that of original promoter. In the induced state however, the differences in the levels of GFP expression varies significantly with some of the promoters being more active and others less active than the original promoter in strain 300. This confirms the value of SPL in the engineering of the strength of promoters. Indeed, the variability created within our very small subset of tested isolates already spans a wide range of promoter activities while still retaining the most important characteristics of the arabinose promoter, its tightness.

Finally we compared the relative activity[5] of both the rationally designed promoters and SPL. Figure 5 depicts that 6 of the mutated promoters are characterized by a higher activity than the original promoter. The most active one, 3h, is twice as strong. 15 promoters have lower activity.

Conclusion

Rationally changing the arabinose promoter as well as using the Synthetic Promoter Library proved to be succesfull in terms of improving the dynamic range of this promoter at the saturation level of inducer. This approach extends the last year DTU team efforts to improve constitutive promoter (SPL for constitutive promoter). It provides the framework for selecting an inducible promoter of a desired strength in a high-troughput manner. We believe that this approach can easily be applied to other inducible promoters.

References

[1] Novick, A. & Weiner, M. “Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon“ Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 43 (1957), 533–556.

[2] Khlebnikov, A., K. Datsenko, T. Skaug, B. L. Wanner, and J. D. Keasling. “Homogeneous expression of the P(BAD) promoter in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of the low-affinity high-capacity AraE transporter.” Microbiology (Reading, England) 147, no. Pt 12 (December 2001): 3241-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11739756.

[3] Guzman, L M, D Belin, M J Carson, and J Beckwith. “Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter.” Journal of bacteriology 177, no. 14 (July 1995): 4121-30. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=177145&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

[4] Morgan-Kiss, Rachael M, Caryn Wadler, and John E Cronan. “Long-term and homogeneous regulation of the Escherichia coli araBAD promoter by use of a lactose transporter of relaxed specificity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99, no. 11 (May 28, 2002): 7373-7. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=124238&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

[5] Alper, Hal, Curt Fischer, Elke Nevoigt, and Gregory Stephanopoulos. “Tuning genetic control through promoter engineering.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, no. 36 (2005): 12678 -12683. http://www.pnas.org/content/102/36/12678.abstract.

[6] Bertram, Hillen. "The application of Tet repressor in prokaryotic gene regulation and expression." Microb Biotechnol. 2008 Jan;1(1):2-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=21261817

[7] Lee SK, Keasling JD. "A Salmonella-based, propionate-inducible, expression system for Salmonella enterica." Gene. 2006 Aug 1;377:6-11. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378111906001788

"

"