Team:Edinburgh/BioSandwich

From 2011.igem.org

BioSandwich: a new assembly protocol

BioSandwich is a new method for assembling multiple BioBricks (which can be RFC10-compliant) in a single reaction. BioSandwich was invented by Dr. Chris French of Edinburgh University, and the Edinburgh iGEM team carried out the first attempts at making it work.

Contents |

Theory

The point of BioBricks is that any combination of parts can be assembled together in any order (as long as the parts are in the same format, e.g. RFC10). The main disadvantage is speed; combining two BioBricks into one can take days, so making a construct that incorporates a significant number of BioBricks can take weeks.

Across the world, most synthetic biology labs are now using homology-based methods such as Gibson assembly. These methods have the advantage of speed: multiple parts can be assembled at once in a single reaction. However, the assembly process relies on the 3' end of every part having homology to the 5' end of another part. These regions of homology determine the order in which the parts assemble. The parts are therefore not reusable as they stand.

BioSandwich is a hybrid that combines many of the benefits of both systems. Parts are reusable because they come in a standard format (much like ordinary BioBricks) with restriction sites flanking the part. The restriction sites are BglII (agatct) in the prefix, and SpeI (actagt) in the suffix. However, these restriction sites are not used directly for assembly; instead they are used to attach short (~35 bp) oligonucleotides (called "spacers"). These spacers serve two purposes:

- They create homology between the end of one part and the start of another; this allows homology-based assembly.

- They can incorporate short meaningful sequences such as ribosome binding sites, linkers for fusion proteins, etc.

Any lab using BioSandwich will want to keep a small library of different spacers for different purposes. Once (carefully chosen) spacers have been attached to each part, homology based assembly can be carried out in a single reaction. Precisely which spacers have been attached to which parts will determine the order of the parts in the final assembly.

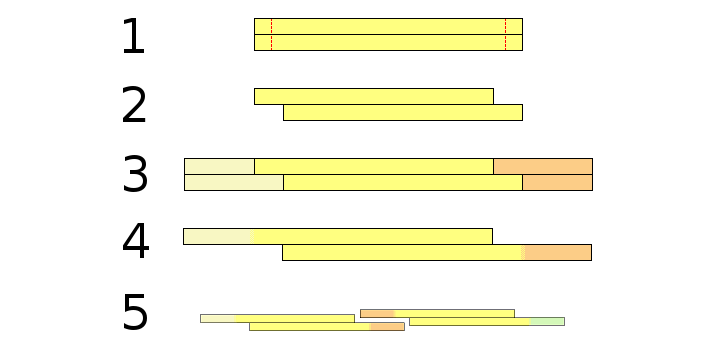

The overall process works roughly like this:

2. They are cut with restriction enzymes.

3. The spacers are annealed.

4. Ligation occurs at the 5' ends of the part only, as only these ends are phosphorylated.

5. [Only required for LIC] Denaturation causes the unligated oligos to fall away. Ideally they should probably be purified out.

6. The parts are placed together, and homology-based assembly is carried out.

Standards

Normal parts

Parts must be free of internal BglII restriction sites (agatct) and SpeI sites (actagt). Each part must be made with a BglII site at the start, and a SpeI site at the end. If compliance with RFC10 is desired, the full format becomes:

gaattcgcggccgcttctagagatct NNN NNN NNN NNt actagtagcggccgctgcag

After cutting with BglII and SpeI, we have the following (shown in frame, which is relevant for fusion proteins):

5' ga tct NNN [...] NNt a 3' 3' a nnn [...] nna tga tc 5'

When a part is used for fusion proteins, the "t" base at the start of the RFC10 suffix becomes the final base of the final codon in the part. Design of the part should take this into account. This is often done by making this final codon GGT, coding for an innocuous glycine residue. (If a fusion protein is not being made, no such consideration is needed. If RFC10-compliance is not required, this "t" base can be replaced with anything.)

Normal spacers

Spacers are designed as a set of oligonucleotides that are attached to the parts. Each type of spacer will be attached upstream of one part and downstream of another. Different forms ("spoligos") of each spacer must be synthesised for each attachment. Thus one might expect that there would be four versions of each spacer; however it is possible to cheat and use three. They should be designed so that the spacer's non-ligating ends are blunt.

The format for the upstream spacers is as follows (both strands shown):

5' ct agc NNN [...] NNN g 3' (forward spoligo) 3' ga tcg nnn [...] nnn cct ag 5' (reverse spoligo ONE)

The format for the downstream spacers is:

5' ct agc NNN [...] NNN g 3' (forward spoligo) 3' g nnn [...] nnn c 5' (reverse spoligo TWO)

The bases indicated in blue should be used for fusion proteins as they result in small hydrophilic amino acids being coded for; however these bases are otherwise optional (though if other bases are chosen, care must be taken not to regenerate the BglII and SpeI sites).

The format of different spacers should be varied to avoid homology. It is recommended that non-coding spacers have an in-frame stop codon, in case they are to be used after a coding part which lacks one.

Vector

A vector is made as a PCR product with a BglII site (agatct) at the 5' end and an XbaI site (tctaga) at the 3' end. Since XbaI produces sticky-ends compatible with SpeI, the vector is compatible with standard spacers.

If one wishes the final products (after insertion into the vector) to be RFC10-compliant, the format for a vector is as follows (BglII and XbaI in bold):

agatct [...] tactagtagcggccgctgcag [ori, cmlR, etc] gaattcgcggccgcttctaga

(The actual vector used by Edinburgh 2011 is shown here.)

Note that a few additional bases must be present at the 5' and 3' ends to allow the restriction enzymes space to work. When spacers are to be annealed, the vector is cut with BglII and XbaI (not SpeI).

Start spacer

For compliance with RFC10, the spacer that connects the vector to the first part must be in the following format:

Spoligos attaching upstream of first part:

5' ctagag NNN [...] NNN g 3' (forward spoligo) 3' gatctc nnn [...] nnn cctag 5' (reverse spoligo ONE)

Spoligos attaching downstream of vector:

5' ctagag NNN [...] NNN g 3' (forward spoligo) 3' tc nnn [...] nnn c 5' (reverse spoligo TWO)

The "a" indicated in red is needed to regenerate the XbaI site, and the "g" indicated in red is needed to complete the RFC10 prefix. The blue bases are still optional, as they were in the normal spacer format.

Protocols

The actual protocols that follow are merely suggestions. Each lab will want to follow its own favourite methods.

Digestion of parts and vector

Each part must be digested separately.

- Parts: digest with BglII and SpeI in NEB Buffer 2

- Vector: digest with BglII and XbaI in NEB Buffer 2 or 3

Each tube gets:

36 uL Water 5 uL DNA 5 uL Buffer 2 uL Enzyme 1 2 uL Enzyme 2

The digestions are then left for 2 hours at 37 C.

Afterwards they are purified with 5 uL glass beads, and eluted to 10 uL EB ([http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Cfrench:DNAextraction1 protocol]).

Ligation of parts and vector to spacer oligos

The parts and vector must now be ligated to the correct spacers...

- Each tube gets:

10 uL Water 5 uL DNA 1 uL Spacer pair #1 1 uL Spacer pair #2 2 uL Ligase buffer 1 uL T4 DNA ligase

- Tubes should then be left for 9 hours at 16 C.

- They must then be purified ([http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Cfrench:DNAextraction1 protocol]).

Tests of BioSandwich

Once you have your parts ligated to spacers, there are multiple ways in which they can be assembled...

We tested several methods. Summaries are found on our Results page.

References

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO (2009) [http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v6/n5/full/nmeth.1318.html Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases]. Nature Methods 6: 343-345 (doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318).

"

"