Team:EPF-Lausanne/Tools/Microfluidics/HowTo2

From 2011.igem.org

Microfluidics how-to part II: building your setup

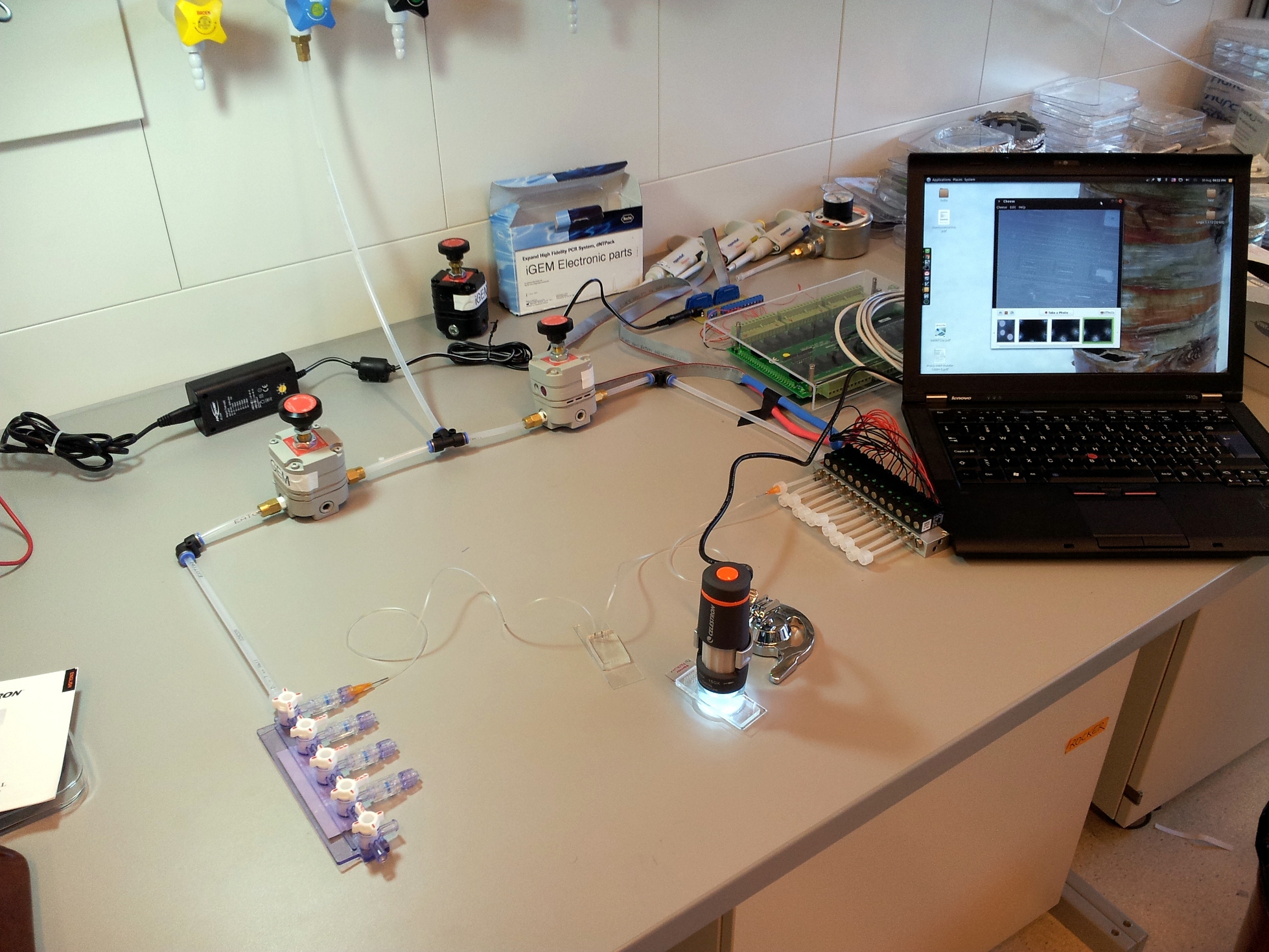

Microfluidics Main | How-To Part I | How-To Part II | TamagotchipMicrofludic chips are nothing but a piece of moulded rubber. To actually get something out of them, an external setup of tubing, compressed air, and valves is needed to flow in fluids and actuate the on-chip valves. To see what's happening, you'll also need some form of microscope. No matter the application of the chip, whether it is designed to study fluid mechanics, to characterise protein-DNA interaction, or even cultivate bacteria and nematodes, the external setup remains essentially the same.

Contents |

A basic microfluidics control setup

Building the setup is relatively straightforward, once you have determined which components are needed and their purpose, and once you have collected the parts. Connecting the components is basic plumbing: just remember to wrap plumber's tape around all metallic screw threads, and then connect the pressure regulators in the correct orientation. With this in mind, we'll go through the parts of a microfluidics setup one by one, and from there you should be able to build your own.

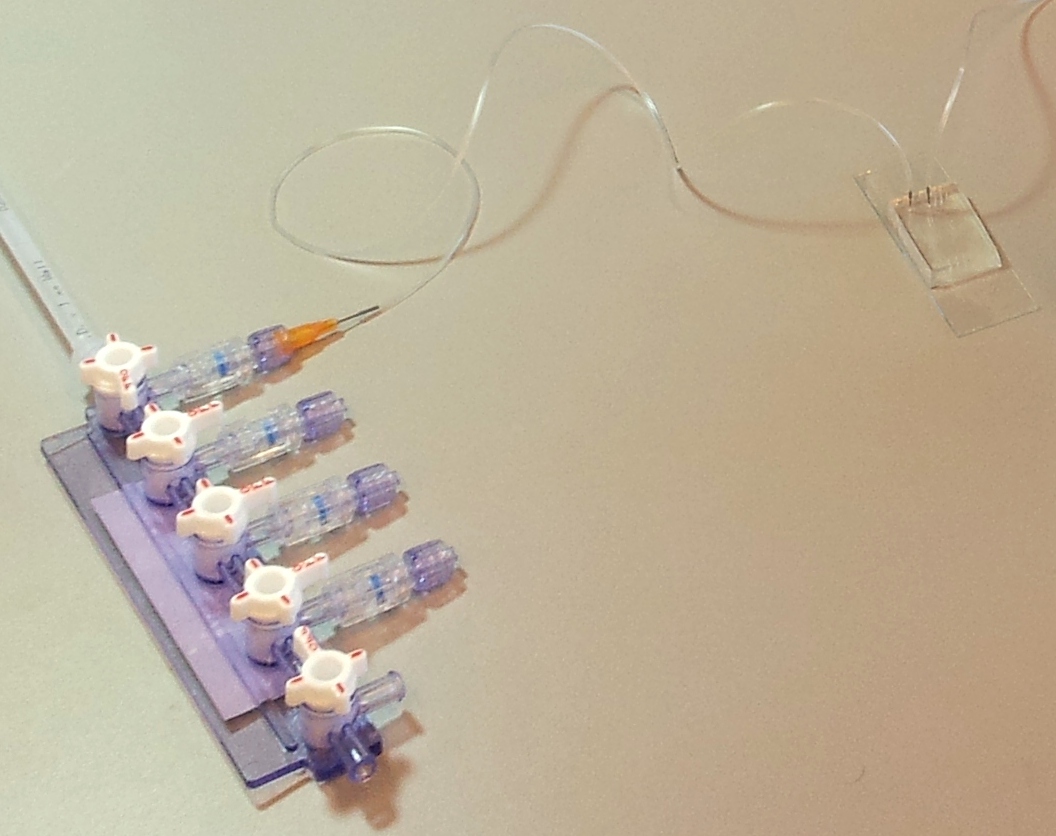

Injecting fluids: mains pressure and tubing, pressure regulators

A microfluidic chip is a network of small channels for fluids. To inject fluid in, a small (.02" inner diameter) tube is filled, then plugged into the chip through one of the punched holes (connecting them with a tubular metal pin). On the other end, the tubes are plugged into a manifold, in turn supplied with air at about 0.2 bar (3 psi), as set by a pressure regulator. The fluid is thus forced into the channels by the compressed air. A syringe can also be used to fill the chip, but it is hard to keep an even pressure (plus you quickly run out of hands).

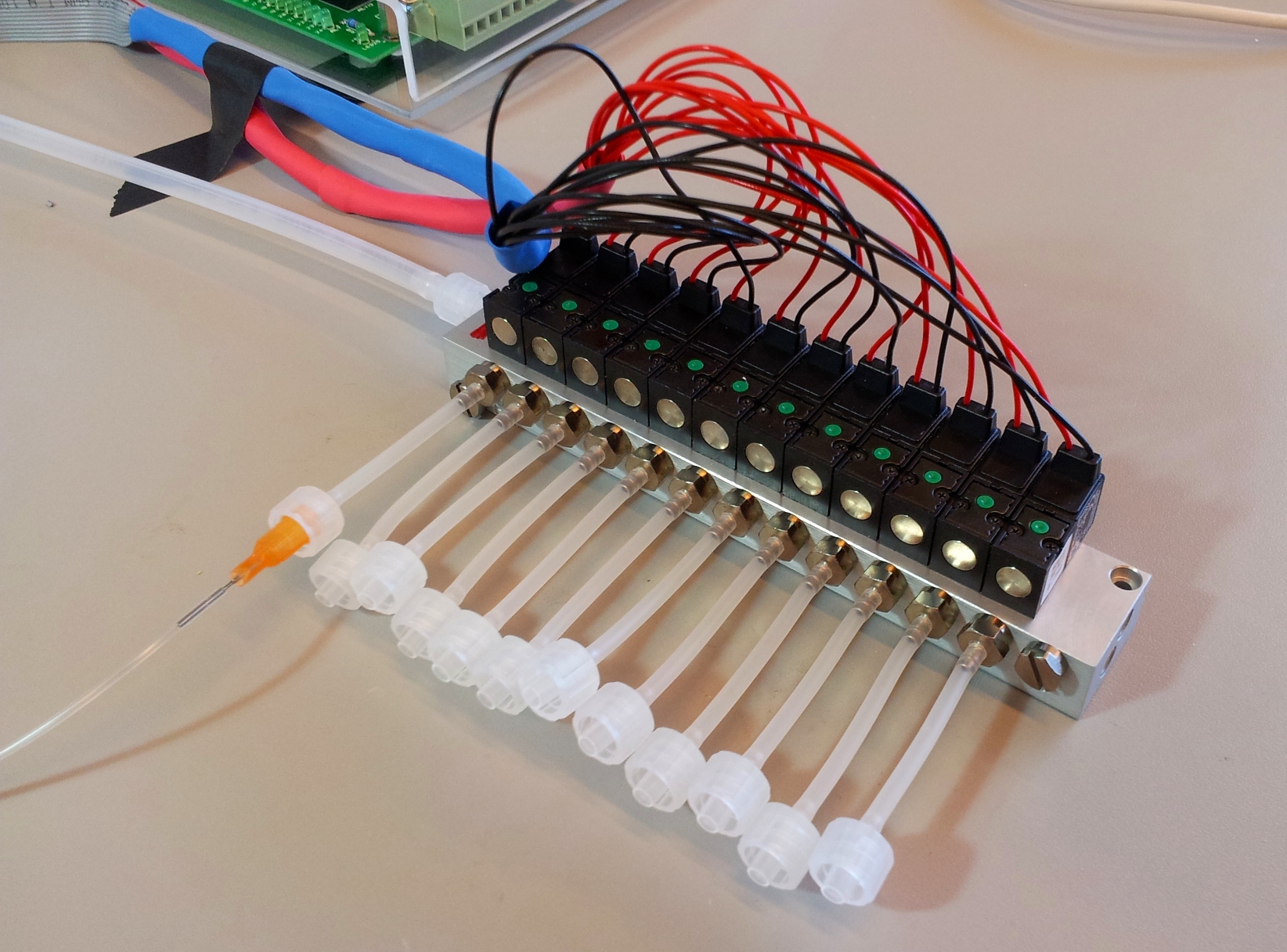

Controlling flow: on-chip valves and 3-way valves.

Our chips have a second control layer above or below the main flow layer. The layers are separated by a thin membrane of PDMS, and their channels overlap in specific locations. When channels of the control layer are pressurized, the membrane bends into the flow layer and blocks it. This creates a microfluidic 'on-chip' valve.

The channels of the control layer are filled in the same way as the flow layer, but require much higher pressure to bend the membrane. We typically used about 2 bar or 30 psi. Each independant valve in the control layer is pressurised by a different tube, regulated by a three-way valve. These switch between high pressure (from mains pressure, and the pressure regulator) to low pressure (atmospheric pressure), and hence allow quick toggling of the microfluidic valve between the open (unpressurised) and closed (pressurised) state. Three way valves come in manually- or electrically-controlled flavours. The manual kind is simpler and more reliable; we use them for the MITOMI chips. The electric kind (more specifically solenoid valves) we use for the web-controlled setup.

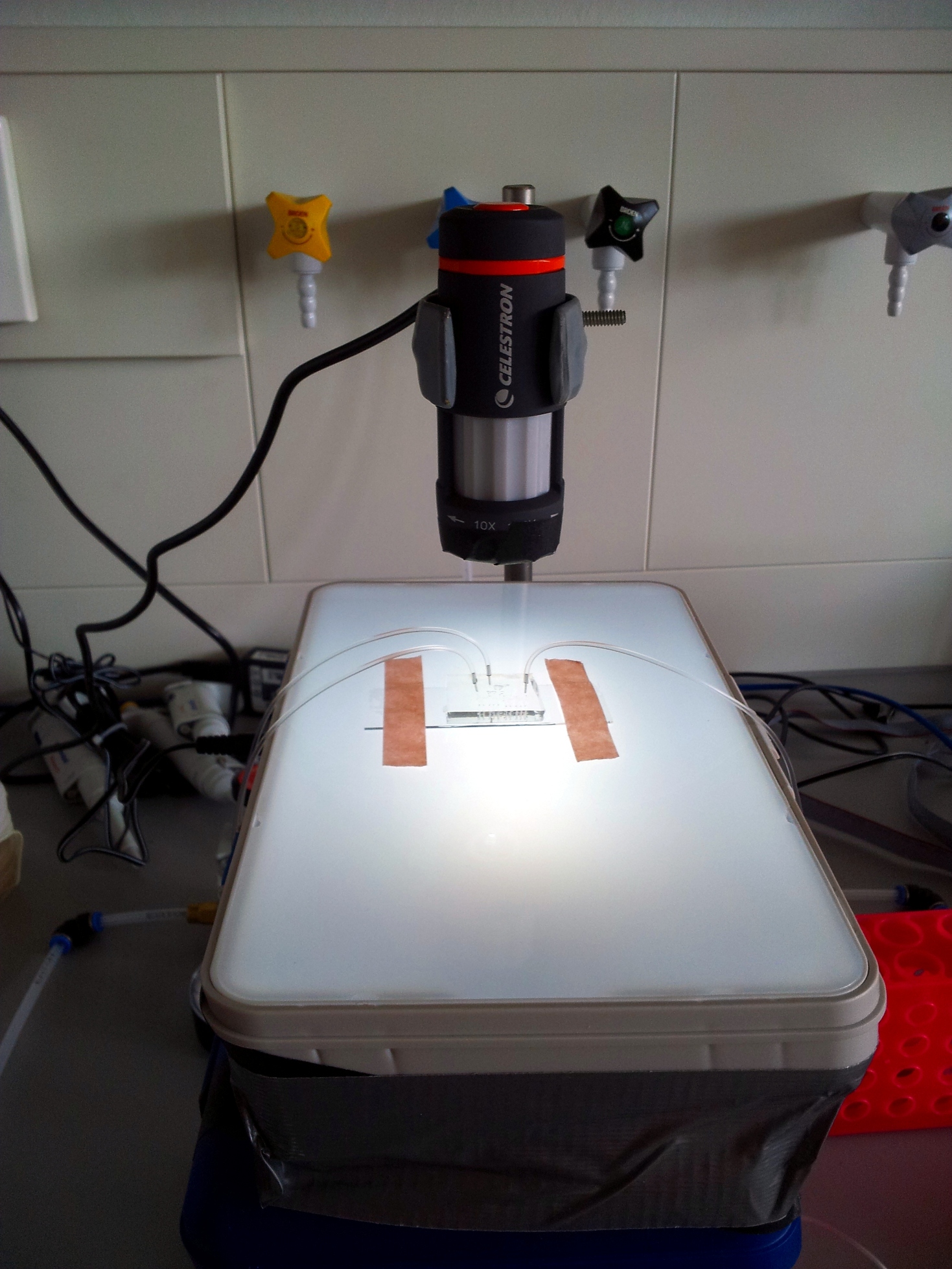

Watching what's going on: the microscope

In our experience, the best tool to look at a microfluidic chip is a low-magnification rear-illuminated binocular microscope. However, we needed a cheap way of viewing the chip on a computer, to then stream the image through internet. We used a toy webcam microscope ($50), and bought a toy light table for rear-illumination ($25). To improve stability and focusing, we fixed the microscope to a chemist's stand and placed the light table on a scissor jack.

- Webcam microscope: [http://www.celestron.com/c3/product.php?ProdID=781 Celestron Deluxe Handheld Digital Microscope]

- Light table: [http://www.artograph.com/products/light_glowbox.htm Artograph GLOBOX]

Hooking it all up: preparing tubes and priming the chip

The presence of bubbles in a channel increases its fluidic resistance, and therefore perturbates or even blocks flow. To avoid this, the first step in running a chip is priming: filling all the channels with fluid, then closing all the micro-valves and keeping pressure applied, until any air remaining in the chip diffuses through the chip walls and disappears.

Once all the channels are filled, the experiments can begin. For the worm chip, we would prime the device with buffer, then introduce the worm after the chip is filled. For the MITOMI chip, we would flow in various biomolecules (neutravidin, bovine serum albumin, antibodies, cell-free extracts) and DNA.

Complete parts list

All the parts used for the pneumatics, with approximate cost in Swiss francs, are listed below. The microscope is an additional cost, but most labs would have one already. The Mac Pro is a lone from EPFL's Biomedical Imaging Group, and the Thinkpad is an oldie that was lying around.

Savings could be made on the pressure regulators, on the valves, and on the EasyDAQ - most setups are better off with manual valves anyway.

| Part | Supplier | Qty | Unit cost [CHF] | Subtotal [CHF] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure Regulator | Bellofram | 2 | 186.00 | 372.00 |

| Manometer 0 - 4.5 bar | Mosch | 2 | 11.20 | 22.40 |

| EasyDAQ USB24mx | EasyDAQ | 1 | 230.00 | 230.00 |

| 12-Solenoid manifold (part S08-1557) | Pneumadyne | 1 | 245.00 | 245.00 |

| Luer barbed adapter, 1/16" (part EW-45503-00) | Cole-Parmer | 1 | 9.20 | 9.20 |

| Luer valve manifold (part EW-06464-87) | Cole-Parmer | 1 | 10.30 | 10.30 |

| Luer lock needles .6 mm ID, 12.7 mm length | Dosieren.net | 100 | 0.28 | 28.00 |

| Tygon .02" tubing, 100 ft | Cole-Parmer | 1 | 50 | 50.00 |

| PE Tubing (6 mm x 4 mm ODxID), 100 m | Serto | 1 | 30 | 30.00 |

| Push-to-connect fittings, for 6 mm OD (various) | Riegler | ~10 | [varies] | ~15.00 |

| Teflon tape, 6 mm | Serto | 1 | 10.92 | 10.92 |

| Total | 1007.82 |

"

"