Team:DTU-Denmark/Background

From 2011.igem.org

What is ...?

Contents |

Introduction

In our project we dig into the fascinating world of sRNA regulation with the aim of engeneering a so-called trap sRNA regulating module and hereby creating a universal tool for a whole new way of regulating gene expression in synthetic biology. To fully understand our project, at basic knowledge of sRNAs, the way they regulate gene expression, the players involved (the RNA chaperone Hfq) and the unique features of the regulation is required. So continue reading if these words are new to you.

An ongoing theme for sRNA regulation is the diversity of its mechanism; some sRNAs are repressors other activators, some act catalytically others non-catalytically, some require Hfq others not and so on. All in all this illustrates the extensive variety of sRNAs and how they over evolution have been tuned to operate in a range of regulatory niches in the cell.

What is sRNA

Many different kinds of RNA molecules are present in the cell; some of these are never translated into proteins. This group is collectively called non-coding RNAs, and includes in addition to small RNA (sRNA) also rRNA and tRNA as well as many other more exotic RNA classes. Bacterial sRNAs are small (normally 50-200 nucleotides) RNA molecules which are extremely interesting as they have been demonstrated to play central regulatory roles in prokaryotes, where they regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level[2][4]. Also eukaryotes (including mammals) use functional analog to sRNAs in post-transcriptional regulation, namely miRNA[4][7].

Cis-Trans-Antisense

Regulatory sRNAs are divided into different sub-groups depended on their genomic locations. Cis-encoded sRNAs are located in the same gene as the one it regulates whereas trans-encoded sRNAs are located somewhere else in the genome. Cis-encoded sRNAs can be further subdivided into sense-RNAs which are coded on the same strand as the mRNA and are thus located at either the 5’ or 3’ untranslated region (UTR) or antisense which are endoded on the complementary strand. Examples of the first class are riboswitches and RNA-thermometers. Antisense RNA share extensive sequence complementarity with its target mRNA in contrast to trans-encoded sRNAs which often only posses a complementary base-pairing region of 8-20 nucleotides [5].

sRNA in Nature

Trans-encoded sRNAs are widespread in nature and an increasing number of sRNAs have been found to regulate critical pathways. In prokaryotes, sRNAs are predominantly involved in response to environmental stimuli or stress situations , eg nutrient starvation, quorum sensing, membrane stress, oxidative stress, and SOS response to DNA damage[2][4]. Examples of well-known sRNAs include; the E.coli RyhB which down regulate non-essential iron-sulfur containing enzymes when iron is limited and the Vibrio Qrr which represses quorum sensing when the cell density is low[7].

How do (trans) sRNAs Work as Regulators

The key-word for sRNA mediated regulation is base-pairing. A part of the sRNA shows limited complementary to the mRNA of the gene it regulates and the sRNA can thus base-pair with the mRNA. The region of base-pairing is typically only 8-20 nucleotides, and often is it only subset of these nucleotides which seem to be critical for regulation[5][7]. This (often imperfect) base-pairing between the sRNA and target mRNA leads to changes in mRNA translation or stability - or both, and thereby influences the target gene expression[2]. sRNAs can be both activators and repressors for gene expression depending on what part of the mRNA molecule they base-pair with, this is summarized in figure.

Repressor sRNA acts negatively by binding to the 5’ UTR often near the ribosome binding site. The binding inhibits translation by impeding ribosome binding and/or target the mRNA for degradation by RNAases, often RNase E. Notice that the degradation entails irreversible regulation[7]. Some sRNAs act stochiometrically meaning that they are co-degradated with the mRNA whereas others act catalytically and are not degraded in the reaction.

Activator sRNA acts positively through an anti-antisense mechanism where sRNA base pairing with the target mRNA disrupts an inhibitory secondary structure sequestering the ribosome-binding site. As a result the ribosome-binding site is liberated and free to bind ribosomes[7].

The Role of Hfq

Hfq is an RNA-binding protein encoded in approximately half of the (in 2002) sequence bacterial genomes and is one of the most abundant proteins in Escherichia coli[3]. Hfq consists of six identical subunits arranged in a ringshape structure[3] with two RNA-binding faces and a long unstructured C-terminal. The sequence motif for RNAs binding to the distal face is 5'-AAYAAYAA-3' (where Y is a pyrimidine, A,T or C), whereas the proximal face seems to favor U-rich sequences[6].

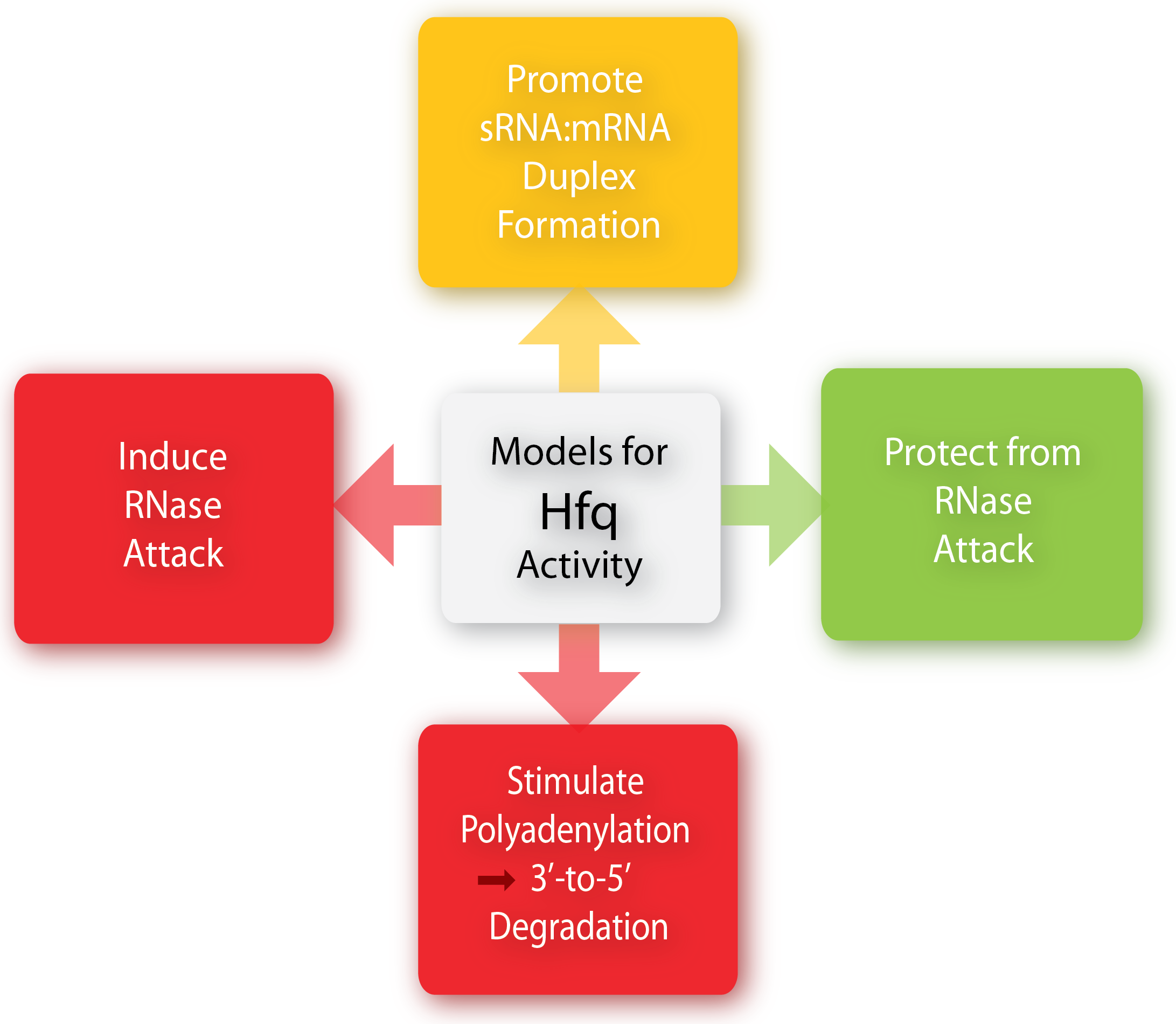

The Hfq chaperone is found to be required for many – but not all – trans-acting antisense sRNAs to form limited base-pairing interactions with their target mRNA[3]. Although Hfq has been the subject of extensive research activity, its specific role, mechanism, and function is still not fully understand and it seems to depend on the specific sRNA-mRNA pair. Several models for the general mechanism of Hfq mediate regulation and how exactly it is facilitated in the cell has been proposed and is summarized in a recent paper by Vogel and Luisi, 2011. Hfq may protect the sRNA from ribonuclease cleavage (often performed by RNase E) in some cases whereas Hfq in other cases induces the cleavage of the sRNA and its target mRNA by RNase E. Furthermore, Hfq may promote the polyadenylation of an mRNA by poly(A) polymerase and hereby triggering the 3’-to-5’ degradation by exoribonucleases[6]. Finally can Hfq promote duplex formation of the sRNA and mRNA, resulting in either translational repression or initiation, depending on whether the sRNA is an activator or repressor. One way by which Hfq can promote sRNA-mRNA duplex formation is by increasing the on-rate for sRNA annealing to target mRNA by promoting base-pairing, either by induce changes in the secondary structure of RNA to favor duplex formation or by simultaneously binding both the sRNA and mRNA hereby increasing the local concentration of the two RNAs[6][1].

Synthetic biology

Synthetic biology is a scientific field concerning the design of new biological functions. The way humans do design is fundamentally different than the evolutionary principles from which life origins. Life has evolved due to an incredible long series of trial-and-error driven and governed by selectional pressure. As this approach have led to an enormous variety of solutions to ways of being alive on earth, from the most sophisticated machine known to mankind, the human brain, to the most resilient microorganisms, there is no doubt to the success of evolution. But what principles may humans apply if we where to do biological design with similar success? One possibility is to guide and facilitate selection, a principle adhered to by breeding programs of the last millennia. This way we might change wolves into dogs or improve crop yields, but there might be and probably are impossibilities of this approach. What if something really useful is only achievable by completely redesigning whole organisms or specific pathways as opposed to simply gradually changing them? A wonderful example of redesign of organisms is the production of human insulin from microorganisms, an application made possible by novel understanding of the components of life and recombinant DNA technology. But from an engineering perspective introducing one recombinant gene is a lot simpler than introducing whole pathways not to speak of designing pathways a priori. The reason microbial insulin production was possible is that the problem reduces to one well characterized component namely the gene encoding insulin. This way the topic of complexity is avoided by utilizing the abilities of the cells to perform the complex task of protein synthesis. Thus one of the most successful cases of applied biotechnology and the redesign of life highlights our current limited ability to understand and control life itself.

To broaden the scope of synthetic biology and biology in general it is necessary to address complexity and not simply reduce scientific inquires to individual components. The emergent properties of life which we ultimately want to understand and control arises from interactions between components. These interactions are often so complex that the unaided human brain might be unable to perceive what is going on. For example the large subunit of the ribosome in simple prokaryotes consists of 2 rRNAs and 34 different proteins all exerting some function. Even if one had the precise structure and function of each component it is unlikely that we would have the ability to fully grasp and understand this subunit of the ribosome. Thus there are clearly limits to human understanding of which one must be aware to successfully conduct research. It is clear that some knowledge of components are required but one might continue to gather knowledge of components for all eternity without gaining understanding of the phenomena of protein synthesis. This indicates that not all knowledge is equal and some knowledge might even be useless to practical applications in the life sciences. Today biology is generating discoveries and insights at an unprecedented rate but despite of the massive gain in knowledge promises of biotechnology are often repeatedly postponed. This indicates that life is often more complicated than anticipated and that new paradigms might be needed to generate useful knowledge of biological systems.

The increasing computing power are emerging as a decisive factor for modern biology. The effect of faster computation have already transformed biology enabling the vast field of bioinformatics and as computing continues to improve its impact on biology are likely to be even greater. More advanced modeling and simulations also known as in silico experiments are enabled, which may guide researchers and designers of biological systems. To construct accurate models or simulations it necessary to have a framework representing the actual system. In terms of mathematics this framework could be a network of interactions and a set of parameters governing the magnitudes of interaction. In developing tools for synthetic biology, such as the trap-RNA system, it is important to provide means of incorporating the tools into both living organisms as well as advanced modeling and simulation.

References

[1] Aiba, Hiroji. “Mechanism of RNA silencing by Hfq-binding small RNAs.” Current Opinion in Microbiology 10, no. 2 (2007): 134-139.

[2] Beisel, Chase L., and Gisela Storz. “Base pairing small RNAs and their roles in global regulatory networks.” FEMS Microbiology Reviews 34, no. 5 (2010): 866-882.

[3] Jousselin, Ambre, Laurent Metzinger, and Brice Felden. “On the facultative requirement of the bacterial RNA chaperone, Hfq.” Trends in Microbiology 17, no. 9 (2009): 399-405.

[4] Levine, Erel, Zhongge Zhang, Thomas Kuhlman, and Terence Hwa. “Quantitative characteristics of gene regulation by small RNA.” PLoS biology. 5, no. 9 (2007).

[5] van Vliet, Arnoud Hm, and Brendan W Wren. “New levels of sophistication in the transcriptional landscape of bacteria.” Genome biology. 10, no. 8 (2009).

[6] Vogel, Jörg, and Ben F Luisi. “Hfq and its constellation of RNA.” Nature reviews. Microbiology 9, no. 8 (2011): 578-589.

[7] Waters, Lauren S., and Gisela Storz. “Regulatory RNAs in Bacteria.” Cell 136, no. 4 (2009): 615-628.

"

"