Team:Imperial College London/Project/Chemotaxis/Results

From 2011.igem.org

| (66 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<h1>Chemotaxis Results</h1> | <h1>Chemotaxis Results</h1> | ||

| - | < | + | <h1>Modelling</h1> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | <h2> | + | <h2>Introduction</h2> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>E.coli is a motile strain of bacteria, which is to say it can swim. It is able to do so by rotating its flagellum, which is a rotating tentacle like structure on the outside of cell. |

| + | Chemotaxis is the movement up concentration gradient of chemoattractants (i.e. malate in our project) and away from poisons. E.coli is too small to detect any concentration | ||

| + | gradient between the two ends of itself, and so they must randomly head in any direction and then compare the new chemoattractant concentration at new point to the previous | ||

| + | 3-4s point. Its motion is described by ‘runs’ and ‘tumbles’, runs refer to a smooth, straight line movement for a number of seconds, while tumble referring to reorientation of | ||

| + | bacteria [1]. Chemoattractant increases transiently raise the probability of ‘tumble’ (or bias), and then a sensory adaptation process returns the bias to baseline, enabling the cell | ||

| + | to detect and respond to further concentration changes. The response to a small step change in chemoattractant concentration in a spatially uniform environment increase the | ||

| + | response time occurs over a 2- to 4- s time span [2]. Saturating changes in chemoattractant can increase the response time to several minutes. </p> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>Many bacterial chemoreceptors belong to a family of transmemberane methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) [3]. Each chemoreceptors on the bacterium has a periplasmic binding domain and a cytoplasmic signaling domain that communicates with the flagellar motors via a phosphorelay sequence involving the CheA, CheY, and CheZ proteins. Modeling of this chemotaxis pathway in single cell is very important, as it will help us to determine, with certain numbers of chemoreceptors, the threshold of chemoattractant concentration where the bacterium is able to detect and the saturation level of chemoattractant where the all the receptors on the bacterium are occupies. A it is believed that the auxin should be kept at a very close region around the root (0.25 cm [4]), therefore it is very important to obtain the number of chemoreceptors needed on individual bacterium that enables the it to stay close to the plant root/seed from modeling. </p> |

| - | + | <p>In addition, modeling of chemotaxis of bacteria population is also valuable for us to capture the overview of movement of bacteria around the plant root; therefore it can potentially inform our project about how and where we can place our bacteria. Under experiment condition, the chemoattractant diffuses all the time from the source. However, in real soil, the root produces malate all the time, therefore we assume that the distribution of chemoattractant outside the root is steady and time-independent. Hence, the modeling of bacteria population chemotaxis will be built with different patterns of chemoattractant distributions.</p> | |

| - | < | + | <h2> Chemotaxis Pathway </h2> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>The chemotaxis pathway in E.Coli is demonstrated in Figure 1. MCPs form stable ternary complexes with the CheA and CheW proteins to generate signals that control the direction of rotation of the flagellar motors [5]. The signaling currency is in the form of phosphoryl groups (p), made available to the CheY and CheB effector proteins through autophosphorylation of CheA[1].CheY-p initiates flagellar responses by interacting with the motor to enance the probability of ‘run’ [1]. CheB-p is part of a sensory adaptation circuit that terminates motor responses [1]. MCP complexes have two alternative CheA autokinase activity; When the receptor is not occupied by chemoattractant, the receptor stimulates CheA activity [1]. The overall flux of phosphoryl groups to inhibited and stimulated states. Changes in attractant concentration shift this distribution, triggering a flagellar response [1]. The ensuing changes in CheB phosphorylation state alter its methylesterase activity, producing a net change in MCP methylation state that cancels the stimulus signal [1]. Therefore, studying of methylation level, phosphorylation level of CheB and CheY are important to understand chemotaxis of single cell. </p> |

| + | <p> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/0/05/0.png" /> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 1[1]: Chemotaxis signaling conponents and oathways for E.Coli.<b></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p>The model based on Spiro et al. (1997) [1] was used to identify candidates of the chemotaxis receptor pathway. The methylation level of receptors, phosphorylation level of CheY and CheB were studied from Spiro’s model(Figure 2-Figue3). With receptor concentration per cell equals to 8x10<sup>-6</sup>mole/L, the lower threshold concentration of chemoattractant that the bacterium start to detect is 10<sup>-8</sup>mole/L. The saturation level is 10<sup>-6</sup>mole/L in which concentration or higher the bacteria’s movements to chemoattractant are less efficient. In addition, the relation between chemoreceptor concentration and the lower threshold and staturation level were also studied (Figure 5). </p> | ||

| + | <p>The quantity that links the CheY-p concentration with the type of motion (run vs. tumble) is called bias. It is defined as the fraction of time spent on the directed movement with respect to the total movement time. The relative concentration of CheYp is converted into motor bias using a Hill function (Euqation 1)[5]. A graph describes bias against CheY-p concentration was shown in Figure 5.</p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/5/58/800px-1.png"alt="" width="250" height="110" /> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/c/cc/P1.png/800px-P1.png" width="800" height="478" /> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 2: [Phosphorylated CheY]/ [CheY]</b></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/1/10/3.png/800px-3.png" /> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 3: [Phosphorylated CheY]/ [CheY]</b></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/0/09/4.png/800px-4.png" /> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 4: [Phosphorylated CheB]/ [CheB]</b></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/8/82/5.png" /> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 6: The dependency of Bias on the concentration of CheY-p</b></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | < | + | <h2>Simulation of chemotaxis of bacteria population</h2> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>The part of modeling focused on creating the movement model of bacteria population for chemotaxis. In order to accurately built this model, the following assumptions are made based on literature: </p> |

| - | </ | + | <p>1) During the directed movement phase, the mean speed of an E. coli equals 24.1 μm/s, varying speed between 17.3 μm/s and 30.9 μm/s [7]. Whereas during the tumbling phase, the speed is significantly smaller and can be neglected. </p> |

| - | < | + | <p>2) E.Coli usually take previous second as their basis on deciding whether the concentration has increased or not. Therefore, in our model the bacteria will be able to compare the concentration of chemattractant at t second and t-1 second. </p> |

| - | <h2> | + | <p>3) In our model, we ignored that E.Coli do not travel in straight line during run, but take curved paths due to unequal firing of flagella. </p> |

| + | <p>4) Our model did not consider the size changing and dividing of bacteria. And the tendency of bacteria congregate into small area due to qurum sensing is also ignored. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Model Designing</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>In chemotaxis, receptors sensing an increase in the concentration of chemoattractant send a signal that suppresses tumbling, and, simultaneously, the receptor becomes more highly methylated. Conversely, a decrease in the chemoattractant concentration increases the tumble frequency and causes receptor demethylation. The tumbling frequency is approximately 1 Hertz, and decreased to almost zero as he bacteria move up a chemtoatic gradient [5]. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p>In the model, the bacteria should be able compare the chemoattractant concentration at current point to the concentration at previous second. If the concentration decreases (i.e. C_t1-C_t2 ≤0), the bacteria will tumble with frequency 1 Hertz. If the concentration increases (C_t1-C_t2 >0), the tumble frequency decreases, and hence the probability of tumbling decreases. From equation 10 in ref [6], we known that even if C_t1-C_t2 >0, the probability of tumbling could decreases to 39%. Therefore, we can conclude the above description into the following statement [8]: </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p style="text-align:center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/1/14/1_2.png/800px-1_2.png"alt="" width="300" height="100" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Chemotaxis of bacteria population under laboratory conditions</h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Under laboratory condition, the chemoattractant diffuses from the source, hence the distribution pattern of chemoattratctant changes with time. In this case, error function (Equation 2) was used to describe the non-steady chemoattractant distribution. The simulation of chemotaxis of 100 bacteria placed 6cm away from the 5mM malate is shown in the movie below. </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/d/dc/1_3.png/800px-1_3.png"alt="" width="430" height="102" /> | ||

| + | <p> <iframe width="850" height="694" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/v0pbKnQVZyQ?hl=zh&fs=1" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe><p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Chemotaxis of bacteria population in Soil</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Malate is used as the chemoattractant in our project, the malate is constantly secreted in the root tip, and the concentration is 0.3mM[9]. In this case, the malate source is always replenished due to continuous secretion from the root tip, the distribution pattern can be considered as steady (i.e. independent of time), and steady state Keler-Segel model was used to demonstrate this distribution (Equation 3 and Equation 5). The distribution was displayed in Figure 7. And Figure 8 shows the position of lower threshold where the bacteria start to response to malate and the saturation level where the chemoreceptors start to loss efficiency. Finally, the animation of bacterial chemotaxis in steady chemoattractant distribution is demonstrated in video below. </p> | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center;"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/6/6b/1_4.png/800px-1_4.png"alt="" width="430" height="180" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/thumb/f/f1/6.png/800px-6.png" /> </p> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 7: Malate distribution (1D)</b></p> | ||

| + | <p> <b>Figure 8: Malate distribution. Red: malate concentration = 10<sup>-8</sup>mol/L,Blue: malate concentration = 10<sup>-6</sup>mol/L</b></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h4>Reference</h4> | ||

| + | <p>[1] Peter A. Spiro, John S. Parkinson, Hands G. Othmer. ‘A model of exciatation and adaptation in bacterial chemotaxis’. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. USA, Vol. 94, pp. 7263-7268, July 1997. Biochemistry</p> | ||

| + | <p>[2] Blocks S. M., Segall J. E. and Berg H.C. (1982) Cell 31, 215-226.</p> | ||

| + | <p>[3] Stock J. B. and Surette M. G. (1996) ‘Escherichia coli and salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology’. Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC). </p> | ||

| + | <p>[4] Andrea Schnepf. ‘3D simulation of nutrient uptake’ </p> | ||

| + | <p>[5] M D Levin, C J Morton-Firth, W N Abouhamad, R B Bourret, and D Bray, ‘Origins of individual swimming behavior in bacteria.’</p> | ||

| + | <p>[6] Vladimirov N, Lovdok L, Lebiedz D, Sourjik V (2008) ‘Dependence of Bacterial Chemotaxis on Gradient Shape and Adaptation Rate’ PloS Comput Biol 4(12): e1000242. Doi:10.1371/journal.pcb1.1000242. </p> | ||

| + | <p>[7] Zenwen Liu and K. Papadopoulos. ‘Unidirectional Motility of Escherichia coli’. | ||

| + | APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY, Oct. 1995, p. 3567–3572 Vol. 61, No. 100099-2240/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology</p> | ||

| + | <p>[8] https://2009.igem.org/Team:Aberdeen_Scotland/chemotaxis</p> | ||

| + | <p>[9] Enrico Martinoia and Doris Rentsch. ‘Malate Compartmentation-Responses to a Complex Metabolism’ Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology Vol. 45: 447-467 (Volume publication date June 1994) DOI: 10.1146/annurev.pp.45.060194.002311</p> | ||

| + | <p>[10] C.J. Brokaw. ‘Chemotaxis of bracken spermatozoids: Implications of electrochemical orientation’. </p> | ||

| + | <p>[11] D.L.Jones, A.M. Prabowo, L.V.Kochian, ‘Kinetics of malate transport and decomposition in acid soils and isolated bacterial populations the effect of microorganisms on root exudation of malate under Al stress.’ Plant and Soil 182:239-247, 1996. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Malate concentration distribution</h2> | ||

| + | <p>For our project, malate is the chemoattractant that results in the movement of E.coli. In this section, we will first model the concentration distribution of the chemoattractant, malate in the soil. Then, we will model the bacteria concentration pattern as a result of this distribution of malate. Finally, we will infer some useful information by analysing the results of the modelling.</p> | ||

| + | <p>We will model the concentration distributions of malate and bacteria using the Keller-Segel model which is governed by the two equations shown below. Solving the equations will give the concentration distributions of the malate and the bacteria respectively | ||

| + | |||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/8/8a/ICL_EqnMalate1.png" /> ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------(1)</p> | ||

| + | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/9/97/ICL_EqnMalate2.png" /> -------------------------------------------------------(2)</p> | ||

| + | <p>s = concentration of chemoattractant<br/> | ||

| + | D = diffusion coefficient of chemoattractant<br/> | ||

| + | f = degradation of chemoattractant<br/> | ||

| + | b = number concentration of bacteria<br/> | ||

| + | µ = bacterial diffusion coefficient (how fast bacteria spread)<br/> | ||

| + | χ = chemotactic coefficient (how sensitive bacteria are)<br/> | ||

| + | g = bacterial cell growth<br/> | ||

| + | h = bacterial cell death | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>The values of the above parameters for E. coli are shown in the following table. These values will be used for the modelling. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="0"> | ||

| + | <tbody> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Parameter description</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Notation</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Value</p></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Initial bacterial concentration</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>b0</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>10^8 cells/ml</p></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Initial attractant concentration</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>s0</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>0.1 mM or 0.1 mol/m3</p></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Bacterial diffusion coefficient</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>µ</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>1.5*10-5 cm2/s</p></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Bacterial chemotactic coefficient</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>χ</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>1.5-75*10-5 cm2/s</p></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>Attractant diffusion coefficient</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>D</p></td> | ||

| + | <td width="205" valign="top"><p>10-5 cm2/s</p></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </tbody> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Reference: Overview of Mathematical Approaches Used to Model Bacterial Chemotaxis II: Bacterial Populations<br /> | ||

| + | The assumptions that we have made are as follow:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>The entire root system is assumed to take the shape of a long cylinder. Hence, a cylindrical coordinate system will be used.</li> | ||

| + | <li>The system is axisymmetric and there is no variation along the vertical length of the root. Hence, <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/e/ea/ICL_EqnMalate3.png" alt="" width="72" height="28" /></li> | ||

| + | <li>The system has reached steady state and is time-independent. Hence, <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/4/48/ICL_EqnMalate4.png" alt="" width="72" height="28" /></li> | ||

| + | <li>Degradation of chemoattractant is first order and is described by f = ks where k is the degradation rate of the chemoattractant.</li> | ||

| + | <li>Bacterial cell growth and death are neglected. Hence, g(b,s) = h(b,s) = 0</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p> Applying the assumptions above, equation (1) becomes</p> | ||

| + | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/d/d7/ICL_EqnMalate5.png" alt="" width="131" height="29" /> </p> | ||

| + | <p> Rearranging,<br /> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/f/f1/ICL_EqnMalate6.png" alt="" width="119" height="30" /> -------------------------------------------------(3)<br /> | ||

| + | Equation (3) is in the form of the modified Bessel equation. Hence, the solution of equation (3) is given by,<br /> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/3/3c/ICL_EqnMalate7.png" alt="" width="186" height="42" /> <br /> | ||

| + | Where K0 is the modified Bessel function.<br /> | ||

| + | Since it is unrealistic for the concentration to increase to infinity, A=0. And applying the boundary condition, the solution becomes,<br /> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/f/fa/ICL_EqnMalate8.png" alt="" width="103" height="42" /> -----------------------------------------------------(4)</p> | ||

| + | <p>The modeling result show that the steady-state pattern of malate distribution. The concentration of malate is a variable against the distance</p> | ||

| + | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/1/14/ICL_Malate1.png" alt="" width="331" height="260" /> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/2/2f/ICL_Malate2.png" alt="" width="303" height="270" /></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </body> | ||

| + | <h1>Assembly</h1> | ||

| + | <p>The receptor genes were synthesised in two fragments. In order to assemble the construct, we | ||

| + | -use CPEC to combine the two fragments</p> | ||

| + | <p>-Cells have been transformed with backbone plasmid pSB1C3 carrying biobrick BBa_K398500, with constitutive promoter J23100,<br> protocol for transformation can be found here.</p> | ||

| + | <p>-transformation of PA2652 fragments into E coli competent cells. Fragment numbers 22 & 23.<br> | ||

| + | -miniprep of the 22 & 23 cells to obtain DNA.<br> | ||

| + | -gibson assembly of 22&23 fragments. | ||

| + | -Due to this we have transformed 5a strain with a high copy plasmid containing ampicillin and kanamycin resistance (AK3 backbone)and sfGFP. These cells have been numbered 17.</p> | ||

| + | <h2>26th of August</h2> | ||

| + | <p> Colony PCR results of CPEC assembled PA2652 construct look promising! Will know for sure when sequencing results arrive next week </p> | ||

| + | <p> <img src=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/f/fa/ICL_PA2652_CPEC_colony_pcr2.jpg width=500px/> | ||

| + | <img src=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2011/0/01/ICL_PA2652_CPEC_colony_pcr_neg_cntrls.jpg width=250px/> | ||

| + | <p>Gel 12: Colony PCR of 19 colonies picked from cells transformed with CPEC assembled PA2652 construct, about half have the correct size insert, these will be inoculated and miniprepped. Gel 13: Two more colony PCRs which were unsuccesfull, followed by five colony PCRs from negative control colonies (assembly of backbone vector without insert)showing backbone vector (6a) in one. The next well is a positive control colony PCR with plasmid 6a. The final two wells are analytical PCRs of the CPEC assembly and negative control with sequencing primers showing the correct size band for the assembled insert.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h1>Testing</h1> | ||

| + | <p>Testing for chemotaxis can be split into qualitative and quantitative assays. Qualitative assays involve putting engineered <i>E. coli</i> and an attractant onto semi-solid agar plates and observe the movement of the microbes. If they can be observed to move towards the attractant source, they are likely to be attracted to the ligand. In quantitative assays, capillaries are filled with different concentrations of the attractant malate. Positive controls are provided by filling identical capillaries with different concentrations of serine, which <i>E. coli</i> naturally move towards. Negative controls are provided by filling capillaries with media that does not contain a source of attractant. The amount of bacteria that swim into each capillary is evaluated by FACS.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> For simplicity, we will be working with Arabidopsis to observe the uptake of bacteria into plant roots. | ||

| + | Arabidopsis thaliana is a common plant model organism. It belongs to the mustard family and fulfils many important requirements for model organisms. As such, its genome has been almost completely sequenced and replicates quickly, producing a large number of seeds. It is easily transformed and many different mutant strains have been constructed to study different aspects (National Institute of Health, no date). While Arabidopsis may not represent plant populations naturally occurring in arid areas threatened by desertification, it is a handy model organism we will be using to study the effect of auxin on roots, observe chemotaxis towards them and look at uptake of bacteria into the roots.</p> | ||

| + | <p>We will be using Arabidopsis to look at the uptake of our engineered bacteria into the plants. For this, we will be using wild type Arabidopsis and E. coli that constitutively express green fluorescent protein. The natural fluorescence produced by plant roots and green fluorescence produced by the bacteria can be used to image the uptake of bacteria using confocal microscopy.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>1. Testing for chemotaxis towards malate</h2> | ||

<p>Experiments involving chemotaxis can be split to two categories, qualitative and quantitative. In the qualitative experiments, we are able to show that bacteria, which we study do or do not move towards a source, however it does not inform us at all about the cell count.</p> | <p>Experiments involving chemotaxis can be split to two categories, qualitative and quantitative. In the qualitative experiments, we are able to show that bacteria, which we study do or do not move towards a source, however it does not inform us at all about the cell count.</p> | ||

<h2>5th of August - Agar plug in assay</h2> | <h2>5th of August - Agar plug in assay</h2> | ||

| Line 223: | Line 376: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<p>Note: Concentration values for 4 & 5 were not obtained from models. They were overestimations to show possible saturation of the medium with attractant. </p> | <p>Note: Concentration values for 4 & 5 were not obtained from models. They were overestimations to show possible saturation of the medium with attractant. </p> | ||

| - | <b>Results</b>: | + | <p><b>Results</b>:</p> |

| - | < | + | </html> |

| - | <p> | + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_nc_0to0.1M.jpg]] |

| - | <p> | + | <html> |

| + | <p><i>Figure 1: Negative control pictured for the attraction E. coli cells, with added attractant malate. Rising consentrations of malate were tested, 0 M, 10<sup>-5</sup> M, 10 <sup>-4</sup> M, 10 <sup>-3</sup> M, 10 <sup>-2</sup> M, 10 <sup>-1</sup> M. Circular colonies are observed with rising concentrations.</i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_nc_0to25mM.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

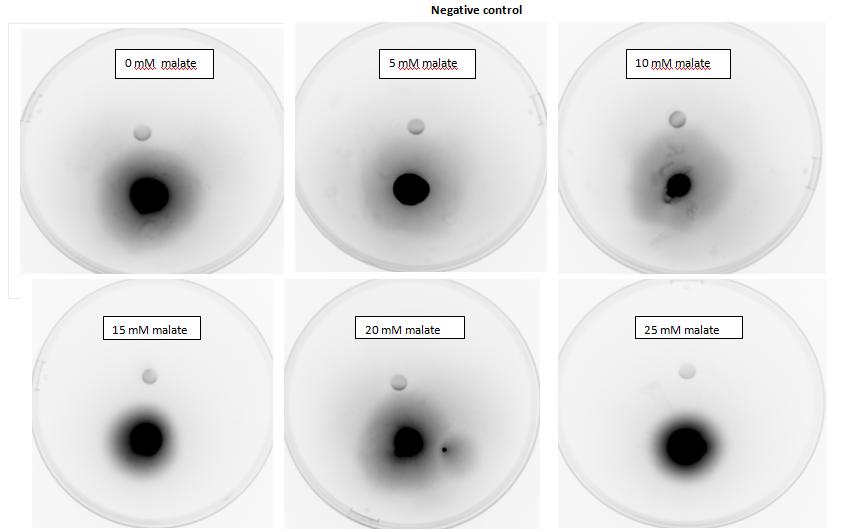

| + | <p><i>Figure 2: Negative control pictured for the attraction E. coli cells, with added attractant malate. Rising consentrations of malate in milimolar range were tested, 0 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM, 20 mM, 25 mM. Circular colonies are observed with rising concentrations.</i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_pc_0to0.1M.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p><i>Figure 3: Positive control pictured for the attraction E. coli cells, with added attractant serine, which is compatible with native E. coli chemoreceptors. Rising consentrations of serine were tested, 0 M, 10<sup>-5</sup> M, 10 <sup>-4</sup> M, 10 <sup>-3</sup> M, 10 <sup>-2</sup> M, 10 <sup>-1</sup> M. Circular colonies are observed with 0 M & 10<sup>-5</sup> M concentrations, result for 10 <sup>-4</sup> M has been rendered void due to mishandling with semi - solid agar. Possible elipse shape of the 10 <sup>-3</sup> M sample can be observed. Directed colony shape towards the attractant source is observed at 10 <sup>-2</sup> M, and circular colony shape is observed in the 10 <sup>-1</sup> M sample.</i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_pc_0to25mM.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p><i>Figure 4: Positive control pictured for the attraction E. coli cells, with added attractant serine, which is compatible with native E. coli chemoreceptors. Rising consentrations of serine in milimolar range were tested, 0 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM, 20 mM, 25 mM. Circular colony can be observed at 0 mM concentration as control, at all other milimolar concentrations directed colony shape towards attractant source can be observed.</i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_mcpS_0to0.1M.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p><i>Figure 5: Modified 5α E. coli cells with mcpS on pRK415 plasmid pictured with added attractant malate. Rising consentrations of malate were tested, 0 M, 10<sup>-5</sup> M, 10 <sup>-4</sup> M, 10 <sup>-3</sup> M, 10 <sup>-2</sup> M, 10 <sup>-1</sup> M. Circular colonies are observed with rising concentrations.</i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_mcpS_0to25mM.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

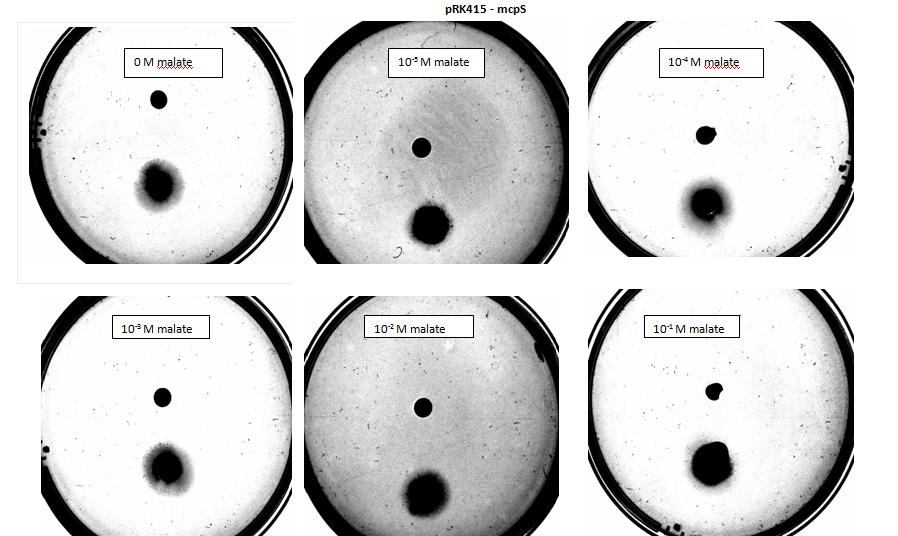

| + | <p><i>Figure 6: Modified 5α E. coli cells with mcpS on pRK415 plasmid pictured with added attractant malate. Rising consentrations of malate in milimolar range were tested, 0 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM, 20 mM, 25 mM. Circular colonies are observed with rising concentrations, with possible directed colony shape at 15mM and 20mM samples.</i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_PA2652_0to0.1M.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p><i>Figure 7: Modified 5α E. coli cells with PA2652 receptor on pSB1C3 plasmid pictured with added attractant malate. Rising consentrations of malate were tested, 0 M, 10<sup>-5</sup> M, 10 <sup>-4</sup> M, 10 <sup>-3</sup> M, 10 <sup>-2</sup> M, 10 <sup>-1</sup> M. Circular colony can be observed for control, elipse shape of colonies can be observed at 10<sup>-5</sup> & 10 <sup>-3</sup>M concentrations. Elipse shaped colony can also be observed at 10 <sup>-4</sup> M however a large spread of bacteria can also be observed to the right side of the plate. Bacteria exposed to 10 <sup>-2</sup> M, 10 <sup>-1</sup> M concentrations, appear as circular colonies, however the colony spread is smaller it is possible due to saturation by malate at high concentrations.</i></p></i></p> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:ICL_semisolid_PA2652_0to25mM.jpg]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

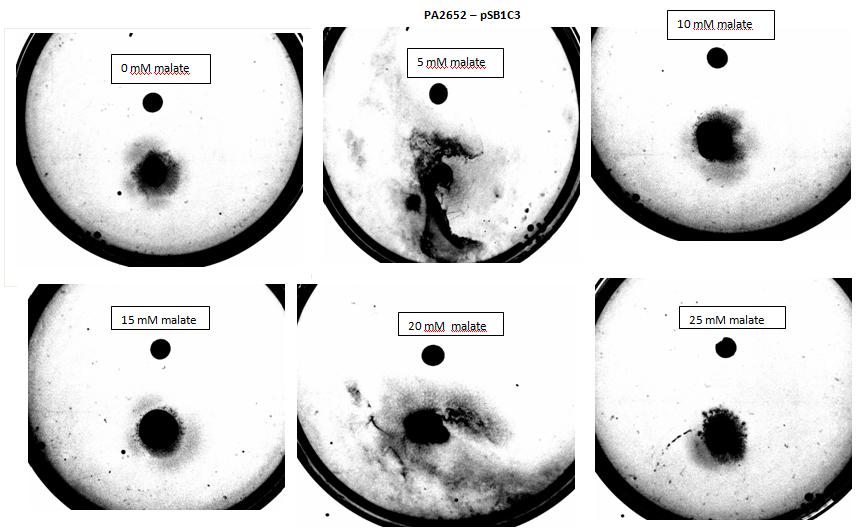

| + | <p><i>Figure 8:Modified 5α E. coli cells with PA2652 receptor on pSB1C3 plasmid pictured with added attractant malate. Rising concentrations of malate in milimolar range were tested, 0 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM, 20 mM, 25 mM. Circular colonies can be observed for 0 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM, 25 mM concentrations. Colonies exposed to 5 mM and 20 mM concentration of attractant were rendered void due to mishandling with semi - solid agar.</i></p> | ||

<h2>18th of August</h2> | <h2>18th of August</h2> | ||

<b>Capillary assay</b> | <b>Capillary assay</b> | ||

<p> quantitative, bacterial movement into a syringe/capillary based on attraction, number of bacteria measured in a capillary after 30min using FACS machine. motility medium & high bacterial OD used..</p> | <p> quantitative, bacterial movement into a syringe/capillary based on attraction, number of bacteria measured in a capillary after 30min using FACS machine. motility medium & high bacterial OD used..</p> | ||

| + | <h2>2. Tests for uptake of bacteria into roots</h2> | ||

| + | <h2>Wednesday, 3 August 2011</h2> | ||

| + | <p>One important part of our project is uptake of our bacteria into plant roots. The observation that this occurs (albeit under controlled lab settings) is new and was only published last year. We attempted to replicate these findings.</p> | ||

| - | + | <p>In preparation, we met with Dr Martin Spitaler who advised us on how to prepare samples for the confocal microscopy. Confocal microscopy is much more precise than conventional light field microscopy as it eliminates background light by focusing the laser through a pinhole (Mark Scott, oral communication). The confocal microscopy will focus on imaging GFP expressing bacteria inside Arabidopsis roots to show that uptake of the bacteria takes place. </p> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | <p> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | <p>Staining of wt roots with DiD, a lipophilic dye that stains the plant membranes and does not interfere with the absorption or emission spectra of GFP and Dendra, was unsuccessful. However, natural fluorescence was measured in a root in a spectrum that does not interfere with measuring GFP. We should therefore not need to dye the roots before imaging.</p> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | </p> | + | |

| - | < | + | <iframe width="420" height="345" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/EqLCzVaBGI0?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe><iframe width="420" height="345" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/Q60tsCjfH4c?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | < | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | < | + | <p><i>Stack of wt Arabidopsis root. The root can be imaged at around 488nm. Imaging carried out by Dr Martin Spitaler.</i></p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | <p>We may also try to stain the roots with propidium iodide, which is also a strong indicator of cell wall break down. </p> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | <p> | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | </ | + | <h2>Thursday, 4 August 2011</h2> |

| - | </html> | + | <p>We prepared the GFP-expressing bacteria for plant infection. They were spun down and media was exchanged prior to incubation at 37°C to reach exponential phase. Bacteria were then spun down and resuspended in wash buffer (5mM MES) to reach OD 30. 8ml, 4ml and 2ml were added to separate flasks, containing 100ml of half-MS media each. 4ml and 6ml of wash buffer were added to the flasks containing 4ml and 2ml bacteria, respectively. 8ml of wash buffer was added to the negative control. Ten Arabidopsis seedlings were distributed into each of the flasks. Incubation was carried out for 15 hours prior to imaging.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Friday, 5 August 2011</h2> | ||

| + | <p>Prior to imaging, roots were washed in PBS to wash off bacteria and facilitate imaging. We imaged the plants incubated with 8ml of bacteria and were able to find bacteria inside one of the roots. A 3D picture was taken of uninfected roots and roots containing bacteria by taking a Z stackk image using confocal microscopy. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <iframe width="425" height="349" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/BBqXWjh8D54?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><i>This video shows a zoom from the top to the bottom of the root. It was put together from successive images taken at different depth levels. The GFP-expressing bacteria are clearly visible within the root.</i></p> | ||

| + | <p>We also imaged roots that did not contain bacteria via a similar Z-stack scan. This image is shown below.</p> | ||

| + | <iframe width="420" height="345" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/SEqt6y749ZQ?rel=0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 09:46, 8 September 2011

Chemotaxis Results

Modelling

Introduction

E.coli is a motile strain of bacteria, which is to say it can swim. It is able to do so by rotating its flagellum, which is a rotating tentacle like structure on the outside of cell. Chemotaxis is the movement up concentration gradient of chemoattractants (i.e. malate in our project) and away from poisons. E.coli is too small to detect any concentration gradient between the two ends of itself, and so they must randomly head in any direction and then compare the new chemoattractant concentration at new point to the previous 3-4s point. Its motion is described by ‘runs’ and ‘tumbles’, runs refer to a smooth, straight line movement for a number of seconds, while tumble referring to reorientation of bacteria [1]. Chemoattractant increases transiently raise the probability of ‘tumble’ (or bias), and then a sensory adaptation process returns the bias to baseline, enabling the cell to detect and respond to further concentration changes. The response to a small step change in chemoattractant concentration in a spatially uniform environment increase the response time occurs over a 2- to 4- s time span [2]. Saturating changes in chemoattractant can increase the response time to several minutes.

Many bacterial chemoreceptors belong to a family of transmemberane methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) [3]. Each chemoreceptors on the bacterium has a periplasmic binding domain and a cytoplasmic signaling domain that communicates with the flagellar motors via a phosphorelay sequence involving the CheA, CheY, and CheZ proteins. Modeling of this chemotaxis pathway in single cell is very important, as it will help us to determine, with certain numbers of chemoreceptors, the threshold of chemoattractant concentration where the bacterium is able to detect and the saturation level of chemoattractant where the all the receptors on the bacterium are occupies. A it is believed that the auxin should be kept at a very close region around the root (0.25 cm [4]), therefore it is very important to obtain the number of chemoreceptors needed on individual bacterium that enables the it to stay close to the plant root/seed from modeling.

In addition, modeling of chemotaxis of bacteria population is also valuable for us to capture the overview of movement of bacteria around the plant root; therefore it can potentially inform our project about how and where we can place our bacteria. Under experiment condition, the chemoattractant diffuses all the time from the source. However, in real soil, the root produces malate all the time, therefore we assume that the distribution of chemoattractant outside the root is steady and time-independent. Hence, the modeling of bacteria population chemotaxis will be built with different patterns of chemoattractant distributions.

Chemotaxis Pathway

The chemotaxis pathway in E.Coli is demonstrated in Figure 1. MCPs form stable ternary complexes with the CheA and CheW proteins to generate signals that control the direction of rotation of the flagellar motors [5]. The signaling currency is in the form of phosphoryl groups (p), made available to the CheY and CheB effector proteins through autophosphorylation of CheA[1].CheY-p initiates flagellar responses by interacting with the motor to enance the probability of ‘run’ [1]. CheB-p is part of a sensory adaptation circuit that terminates motor responses [1]. MCP complexes have two alternative CheA autokinase activity; When the receptor is not occupied by chemoattractant, the receptor stimulates CheA activity [1]. The overall flux of phosphoryl groups to inhibited and stimulated states. Changes in attractant concentration shift this distribution, triggering a flagellar response [1]. The ensuing changes in CheB phosphorylation state alter its methylesterase activity, producing a net change in MCP methylation state that cancels the stimulus signal [1]. Therefore, studying of methylation level, phosphorylation level of CheB and CheY are important to understand chemotaxis of single cell.

Figure 1[1]: Chemotaxis signaling conponents and oathways for E.Coli.

The model based on Spiro et al. (1997) [1] was used to identify candidates of the chemotaxis receptor pathway. The methylation level of receptors, phosphorylation level of CheY and CheB were studied from Spiro’s model(Figure 2-Figue3). With receptor concentration per cell equals to 8x10-6mole/L, the lower threshold concentration of chemoattractant that the bacterium start to detect is 10-8mole/L. The saturation level is 10-6mole/L in which concentration or higher the bacteria’s movements to chemoattractant are less efficient. In addition, the relation between chemoreceptor concentration and the lower threshold and staturation level were also studied (Figure 5).

The quantity that links the CheY-p concentration with the type of motion (run vs. tumble) is called bias. It is defined as the fraction of time spent on the directed movement with respect to the total movement time. The relative concentration of CheYp is converted into motor bias using a Hill function (Euqation 1)[5]. A graph describes bias against CheY-p concentration was shown in Figure 5.

Figure 2: [Phosphorylated CheY]/ [CheY]

Figure 3: [Phosphorylated CheY]/ [CheY]

Figure 4: [Phosphorylated CheB]/ [CheB]

Figure 6: The dependency of Bias on the concentration of CheY-p

Simulation of chemotaxis of bacteria population

The part of modeling focused on creating the movement model of bacteria population for chemotaxis. In order to accurately built this model, the following assumptions are made based on literature:

1) During the directed movement phase, the mean speed of an E. coli equals 24.1 μm/s, varying speed between 17.3 μm/s and 30.9 μm/s [7]. Whereas during the tumbling phase, the speed is significantly smaller and can be neglected.

2) E.Coli usually take previous second as their basis on deciding whether the concentration has increased or not. Therefore, in our model the bacteria will be able to compare the concentration of chemattractant at t second and t-1 second.

3) In our model, we ignored that E.Coli do not travel in straight line during run, but take curved paths due to unequal firing of flagella.

4) Our model did not consider the size changing and dividing of bacteria. And the tendency of bacteria congregate into small area due to qurum sensing is also ignored.

Model Designing

In chemotaxis, receptors sensing an increase in the concentration of chemoattractant send a signal that suppresses tumbling, and, simultaneously, the receptor becomes more highly methylated. Conversely, a decrease in the chemoattractant concentration increases the tumble frequency and causes receptor demethylation. The tumbling frequency is approximately 1 Hertz, and decreased to almost zero as he bacteria move up a chemtoatic gradient [5].

In the model, the bacteria should be able compare the chemoattractant concentration at current point to the concentration at previous second. If the concentration decreases (i.e. C_t1-C_t2 ≤0), the bacteria will tumble with frequency 1 Hertz. If the concentration increases (C_t1-C_t2 >0), the tumble frequency decreases, and hence the probability of tumbling decreases. From equation 10 in ref [6], we known that even if C_t1-C_t2 >0, the probability of tumbling could decreases to 39%. Therefore, we can conclude the above description into the following statement [8]:

Chemotaxis of bacteria population under laboratory conditions

Under laboratory condition, the chemoattractant diffuses from the source, hence the distribution pattern of chemoattratctant changes with time. In this case, error function (Equation 2) was used to describe the non-steady chemoattractant distribution. The simulation of chemotaxis of 100 bacteria placed 6cm away from the 5mM malate is shown in the movie below.

Chemotaxis of bacteria population in Soil

Malate is used as the chemoattractant in our project, the malate is constantly secreted in the root tip, and the concentration is 0.3mM[9]. In this case, the malate source is always replenished due to continuous secretion from the root tip, the distribution pattern can be considered as steady (i.e. independent of time), and steady state Keler-Segel model was used to demonstrate this distribution (Equation 3 and Equation 5). The distribution was displayed in Figure 7. And Figure 8 shows the position of lower threshold where the bacteria start to response to malate and the saturation level where the chemoreceptors start to loss efficiency. Finally, the animation of bacterial chemotaxis in steady chemoattractant distribution is demonstrated in video below.

Figure 7: Malate distribution (1D)

Figure 8: Malate distribution. Red: malate concentration = 10-8mol/L,Blue: malate concentration = 10-6mol/L

Reference

[1] Peter A. Spiro, John S. Parkinson, Hands G. Othmer. ‘A model of exciatation and adaptation in bacterial chemotaxis’. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. USA, Vol. 94, pp. 7263-7268, July 1997. Biochemistry

[2] Blocks S. M., Segall J. E. and Berg H.C. (1982) Cell 31, 215-226.

[3] Stock J. B. and Surette M. G. (1996) ‘Escherichia coli and salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology’. Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC).

[4] Andrea Schnepf. ‘3D simulation of nutrient uptake’

[5] M D Levin, C J Morton-Firth, W N Abouhamad, R B Bourret, and D Bray, ‘Origins of individual swimming behavior in bacteria.’

[6] Vladimirov N, Lovdok L, Lebiedz D, Sourjik V (2008) ‘Dependence of Bacterial Chemotaxis on Gradient Shape and Adaptation Rate’ PloS Comput Biol 4(12): e1000242. Doi:10.1371/journal.pcb1.1000242.

[7] Zenwen Liu and K. Papadopoulos. ‘Unidirectional Motility of Escherichia coli’. APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY, Oct. 1995, p. 3567–3572 Vol. 61, No. 100099-2240/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology

[8] https://2009.igem.org/Team:Aberdeen_Scotland/chemotaxis

[9] Enrico Martinoia and Doris Rentsch. ‘Malate Compartmentation-Responses to a Complex Metabolism’ Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology Vol. 45: 447-467 (Volume publication date June 1994) DOI: 10.1146/annurev.pp.45.060194.002311

[10] C.J. Brokaw. ‘Chemotaxis of bracken spermatozoids: Implications of electrochemical orientation’.

[11] D.L.Jones, A.M. Prabowo, L.V.Kochian, ‘Kinetics of malate transport and decomposition in acid soils and isolated bacterial populations the effect of microorganisms on root exudation of malate under Al stress.’ Plant and Soil 182:239-247, 1996.

Malate concentration distribution

For our project, malate is the chemoattractant that results in the movement of E.coli. In this section, we will first model the concentration distribution of the chemoattractant, malate in the soil. Then, we will model the bacteria concentration pattern as a result of this distribution of malate. Finally, we will infer some useful information by analysing the results of the modelling.

We will model the concentration distributions of malate and bacteria using the Keller-Segel model which is governed by the two equations shown below. Solving the equations will give the concentration distributions of the malate and the bacteria respectively

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------(1)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------(1)

-------------------------------------------------------(2)

-------------------------------------------------------(2)

s = concentration of chemoattractant

D = diffusion coefficient of chemoattractant

f = degradation of chemoattractant

b = number concentration of bacteria

µ = bacterial diffusion coefficient (how fast bacteria spread)

χ = chemotactic coefficient (how sensitive bacteria are)

g = bacterial cell growth

h = bacterial cell death

The values of the above parameters for E. coli are shown in the following table. These values will be used for the modelling.

Parameter description |

Notation |

Value |

Initial bacterial concentration |

b0 |

10^8 cells/ml |

Initial attractant concentration |

s0 |

0.1 mM or 0.1 mol/m3 |

Bacterial diffusion coefficient |

µ |

1.5*10-5 cm2/s |

Bacterial chemotactic coefficient |

χ |

1.5-75*10-5 cm2/s |

Attractant diffusion coefficient |

D |

10-5 cm2/s |

Reference: Overview of Mathematical Approaches Used to Model Bacterial Chemotaxis II: Bacterial Populations

The assumptions that we have made are as follow:

- The entire root system is assumed to take the shape of a long cylinder. Hence, a cylindrical coordinate system will be used.

- The system is axisymmetric and there is no variation along the vertical length of the root. Hence,

- The system has reached steady state and is time-independent. Hence,

- Degradation of chemoattractant is first order and is described by f = ks where k is the degradation rate of the chemoattractant.

- Bacterial cell growth and death are neglected. Hence, g(b,s) = h(b,s) = 0

Applying the assumptions above, equation (1) becomes

![]()

Rearranging,

![]() -------------------------------------------------(3)

-------------------------------------------------(3)

Equation (3) is in the form of the modified Bessel equation. Hence, the solution of equation (3) is given by,

![]()

Where K0 is the modified Bessel function.

Since it is unrealistic for the concentration to increase to infinity, A=0. And applying the boundary condition, the solution becomes,

![]() -----------------------------------------------------(4)

-----------------------------------------------------(4)

The modeling result show that the steady-state pattern of malate distribution. The concentration of malate is a variable against the distance

"

"