Team:Macquarie Australia/Project

From 2011.igem.org

(→Background) |

m (→Aims) |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

3. Assemble an operon consisting of the heme-oxygenase and bacteriophytochrome BioBrick parts. | 3. Assemble an operon consisting of the heme-oxygenase and bacteriophytochrome BioBrick parts. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | 4. Optimise the gene expression from the operon such that the bacteriophytochrome light switch works without requiring the addition of biliverdin. | + | 4. Optimise the gene expression from the operon such that the bacteriophytochrome light switch works without requiring the addition of biliverdin. <br> |

= '''The Experiments''' = | = '''The Experiments''' = | ||

Latest revision as of 09:53, 5 October 2011

Contents |

Our project

Background

Phytochromes were first discovered in plants and were found to be associated with photo-perception - indeed, they are classed as photoreceptors. They are now known to exist in all plant species as well as some species of fungi and bacteria [2,5]. Plants use phytochromes as ambient light sensors involved for morphological development such as the germination of seeds, flower generation, responses to sunlight and position relative to shade [1,5,6,7,8,9]. Phytochrome proteins act as light sensors by absorbing red/far red light, however some phytochromes can detect light between the UV-A to far-red regions.

Bacteriophytochromes act as photoreceptors for bacteria, mediating sensory responses to their light environment [4,6]. Bacteriophytochromes can also act as protein kinases triggered by light. These are able to modify or regulate various components in the cell such as protein activity and the synthesis of the light harvesting complex (chromophore) via the promotion of transcription factors. By doing so, they create what can be thought of as a “light switch”. The light switch bacteriophytochrome that is utilised by Agrobacterium and Deinococcus has the domain structure: PAS-GAF-PHY-HisKinase, and is able to cause a shift in conformation of the chromophore complex according to the wavelength absorbed. Essentially, what this means is that two different chromophores from two different phytochromes can activate two separate pathways due to their slight differences in light absorbance affinity.

For a light switch to be self-sufficient and fully functional two main components are required: 1) A heme oxygenase enzyme and 2) the bacteriophytochrome coupled with ribosome binding sites. The heme oxygenase is required for the degradation of the porphyrin heme (which is naturally occuring in E.coli) to form the linear tetrapyrrole biliverdin [10]. Biliverdin is then able to bind to the GAF domain of the bacteriophytochrome, forming the chromophore complex. A colour is thus produced according to the ratio of red to far-red light absorbed.

Phytochromes exist in a default off state (Pr) where the protein is biologically inactive [1]. In this state, the phytochrome absorbs red light and converts to the far red state (Pfr). A phytochrome in the far red state is considered to be in the active form, which absorbs far-red light. When in the Pr form, the phytochrome expresses a blue colour. If the balance of red/far red light absorbed shifts to the far red side, then the phytochrome is able to isomerise to a green colour [2,3,4]. Essentially, the phytochrome acts as an oscillating switch - hit it with red light and the chromophore emits a green colour, hit it with far red light and the chromophore emits a blue colour. This holds enormous potential for differential expression of two different kinase pathways (remember the phytochrome structure) while at the same time providing a clear detection mechanism.

The bacteriophytochrome vector will be transformed into E. coli competent BL21 (DE3) cells, which contains the T7 RNA polyermase for the expression of T7 promoter regulated operons. As E. coli do not contain a native heme oxygenase gene, it must be incorporated into the final assembled operon construct along with a T7 promoter and the bacteriophytochrome genes from Deinococcus and Agrobacterium for the "light switch" to be self-assembled and functional.

References

1. Park, C. M., Kim, J. I., Yang, S. S., Kang, J. G., Kang, J. H., Shim, J. Y., Chung, Y. H., Park, Y. M. & Song, P. S. (2000). A second photochromic bacteriophytochrome from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: spectral analysis and down-regulation by light. Biochemistry 39, 10840-7.

2. Karniol, B. & Vierstra, R. D. (2003). The pair of bacteriophytochromes from Agrobacterium tumefaciens are histidine kinases with opposing photobiological properties. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 2807-12.

3. Tarutina, M., Ryjenkov, D. A. & Gomelsky, M. (2006). An unorthodox bacteriophytochrome from Rhodobacter sphaeroides involved in turnover of the second messenger c-di-GMP. The Journal of biological chemistry 281, 34751-8.

4. Giraud, E., Fardoux, J., Fourrier, N., Hannibal, L., Genty, B., Bouyer, P., Dreyfus, B. & Vermeglio, A. (2002). Bacteriophytochrome controls photosystem synthesis in anoxygenic bacteria. Nature 417, 202-5.

5. Davis, S. J., Vener, A. V. & Vierstra, R. D. (1999). Bacteriophytochromes: phytochrome-like photoreceptors from nonphotosynthetic eubacteria. Science 286, 2517-20.

6. Wilde, A., Fiedler, B. & Borner, T. (2002). The cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph2 inhibits phototaxis towards blue light. Molecular microbiology 44, 981-8.

7. Rockwell, N. C., Su, Y. S. & Lagarias, J. C. (2006). Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annual review of plant biology 57, 837-58.

8. Halliday, K. J. (2007). Photoreceptors and Associated Signaling I: Phytochromes. In Encyclopedia of Plant and Crop Science, pp. 881-884. 0 vols. Taylor & Francis.

9. Wagner, J. R., Zhang, J., Brunzelle, J. S., Vierstra, R. D. & Forest, K. T. (2007). High resolution structure of Deinococcus bacteriophytochrome yields new insights into phytochrome architecture and evolution. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 12298-309.

10. Grangeiro, N. M., Aguiar, J. A., Chaves, H. V., Silva, A. A., Lima, V., Benevides, N. M., Brito, G. A., da Graca, J. R. & Bezerra, M. M. (2011). Heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide-biliverdin pathway may be involved in the antinociceptive activity of etoricoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor. Pharmacological reports : PR 63, 112-9.

Aims

The objective in this project is to build and characterise a biological light switch in E. coli. This will involve construction of heme-oxygenase and bacteriophytochrome BioBrick parts. In 2010 the Macquarie Team cloned bacteriophytochrome from two sources. They showed that when one was expressed, it was functionally assembled when incubated with exogenous biliverdin and able to elicit a colour change when excited with far-red light. However, the part created is not directly usable as a BioBrick as it contains an internal EcoRI site (Deinococcus radiodurans phytochrome) and 2 PstI sites (Agrobacterium tumefaciens phytochrome). As biliverdin is not native to E. coli, the addition of heme oxygenase is required for the synthesis of bilivedin, enabling the self-assembly of the light switch. The 2010 Macquarie Team had managed to combine a ribosome binding site (RBS) to all 3 proteins of interest.

Hence, the aims of the team this year are to complete the light switch construction:

1. Assemble 3 fully functional BioBricks which are functionally expressed in E.coli.

2. Remove the restriction sites from the bacteriophytochrome which are incompatible with BioBrick assembly.

3. Assemble an operon consisting of the heme-oxygenase and bacteriophytochrome BioBrick parts.

4. Optimise the gene expression from the operon such that the bacteriophytochrome light switch works without requiring the addition of biliverdin.

The Experiments

Primer Design

Primer Sequence Melting temp (°C) BB-FWD 5'- GAA TTC GCG GCC GCT TCT AGA -3' 59.7 BB-REV 5'- CTG CAG CGG CCG CTA CTA GTA -3' 61 T7-BB-FWD 5'- GAA TTC GCG GCC GCT TCT AGA TCT CGA TCC CGC G -3' 69.4 T7-BB-REV 5'- CTG CAG CGG CCG CTA CTA GTA GAG GGG AAT TGT TAT -3' 66.5 HO1-BB-FWD 5'- GCG GCC GCT TCT AGA CTT TAA GAA GGA GAT ATA C -3' 61.9 HO1-BB-REV 5'- GCG GCC GCT ACT AGT ACT TTC GGG CTT TGT TAG C -3' 67 DR-BB-FWD 5'- TCG CGG CCG CTT CTA GAA GGA GGG CTG CTA TGA GC -3' 71 DR-BB-REV 5'- GCG GCC GCT ACT AGT ATC AGG CAT CGG CGG CTC CCG G -3' 68.7 DR-M-FWD 5'- TTG CTG ATT CTG GAG TTC GAG CCG ACG GAG -3' 63.5 DR-M-REV 5'- CTC CGT CGG CTC GAA CTC CAG AAT CAG CAA -3' 61.7 AT-BB-FWD 5'- CGC GGC CGC TTC TAG AGA TTA GGA GGG CTG CTA TGA G -3' 69.1 AT-BB-REV 5'- GCG GCC GCT ACT AGT AGA TTT CAG GCA ATT TTT TCC -3' 64.3 AT-M1-FWD 5'- GTC CCT GCA TTA TCT TCA GAT GAT ATC AGA -3' 53.8 AT-M1-REV 5'- TCT GAT ATC ATC TGA AGA TAA TGC AGG GAC -3' 55.7 AT-M2-FWD 5'- GTG TTT CAG AGG CTT CAG CGG GTG GAG GA -3' 63.9 AT-M2-REV 5'- TCC TCC ACC CGC TGA AGC CTC TGA AAC AC -3' 64.5 BB - BioBrick compatible, M - Mutagenic primer (Italics - base mutation), Bold - Restriction sites

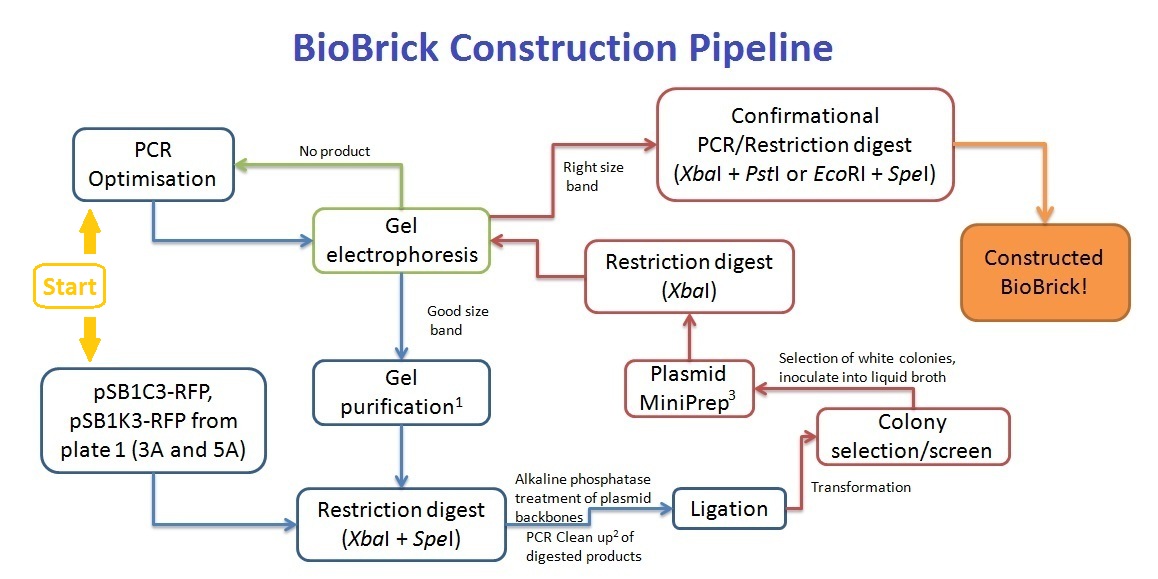

Primers were designed such that the amplicon would consist of at least the XbaI site or SpeI site and be restricted by the length of the primers. As such, an EcoRI or PstI restriction digest would not work for our BioBrick construction, resulting in the XbaI and SpeI digestion for the ligation. This creates a problem - the inserted coding sequence would be incorrectly orientated - SpeI ligating with XbaI instead. To solve this problem, we've decided to screen at least 10 colonies that grow on the antibiotic resistant plates, and perform an XbaI digest to screen for inserts that are in the right orientation. Colony PCR was trialled, but due to the lack of difference between the right and wrong orientation of inserts (only 2 single base difference), the screening method was abandoned (see notebook).

BioBrick Construction Method

1 - Qiagen Gel extraction kit, 2 - Sigma PCR clean up kit, 3 - Qiagen Spin Miniprep kit

Along with the PCR clean up of the pre-ligation products, the cut plasmid backbone was separated on a gel, and gel purified to remove any red fluorescent protein gene products.

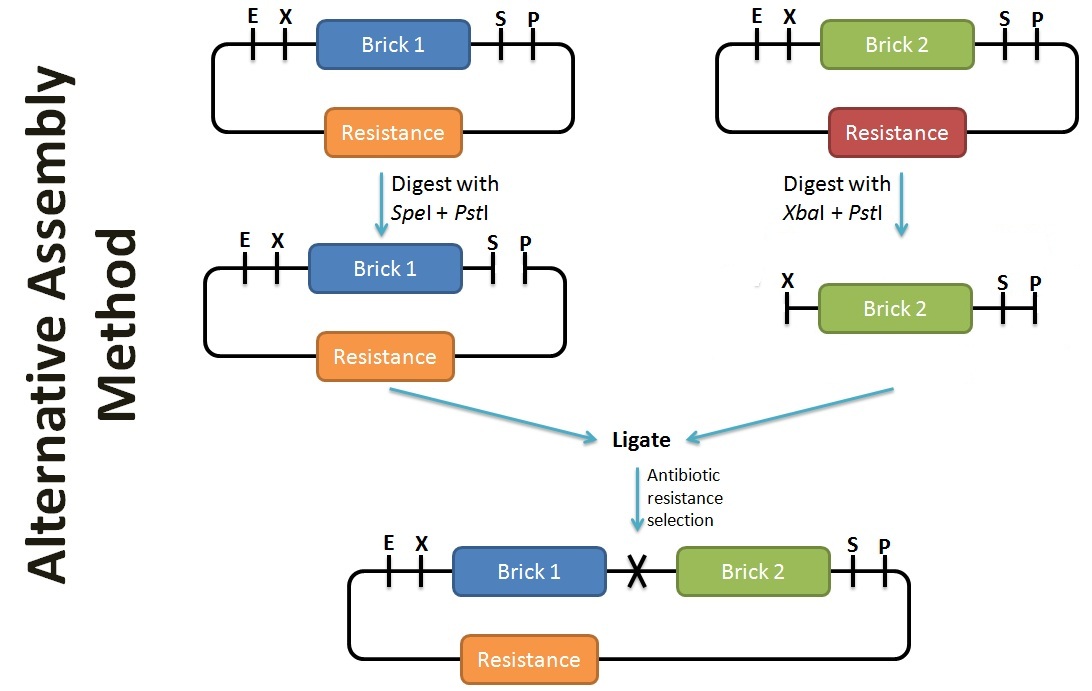

Alternative Assembly Method

In contrast to the assembly protocol as proposed by iGEM, we've adopted a slightly different protocol. This can be applied when the antibiotic backbone of one of the parts remains the same (such as preparation for submission), while inserting the desired part. The screening of successful assembly can either be by protein expression (eg. T7 promoter part + GFP = fluoresce), PCR using BioBrick primers, or by plasmid extraction (successful assembly would have a larger band size). To enhance the efficiency of the assembly, alkaline phophatase treatment should be performed on the plasmid with the selection resistance to minimise re-ligation.

"

"