Team:Washington/Celiacs/Results

From 2011.igem.org

(→Calculating the catalytic efficiency) |

|||

| (52 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<center><big><big><big><big>'''Gluten Destruction: Results Summary'''</big></big></big></big></center><br><br> | <center><big><big><big><big>'''Gluten Destruction: Results Summary'''</big></big></big></big></center><br><br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

='''Testing Kumamolisin-As against SC-PEP'''= | ='''Testing Kumamolisin-As against SC-PEP'''= | ||

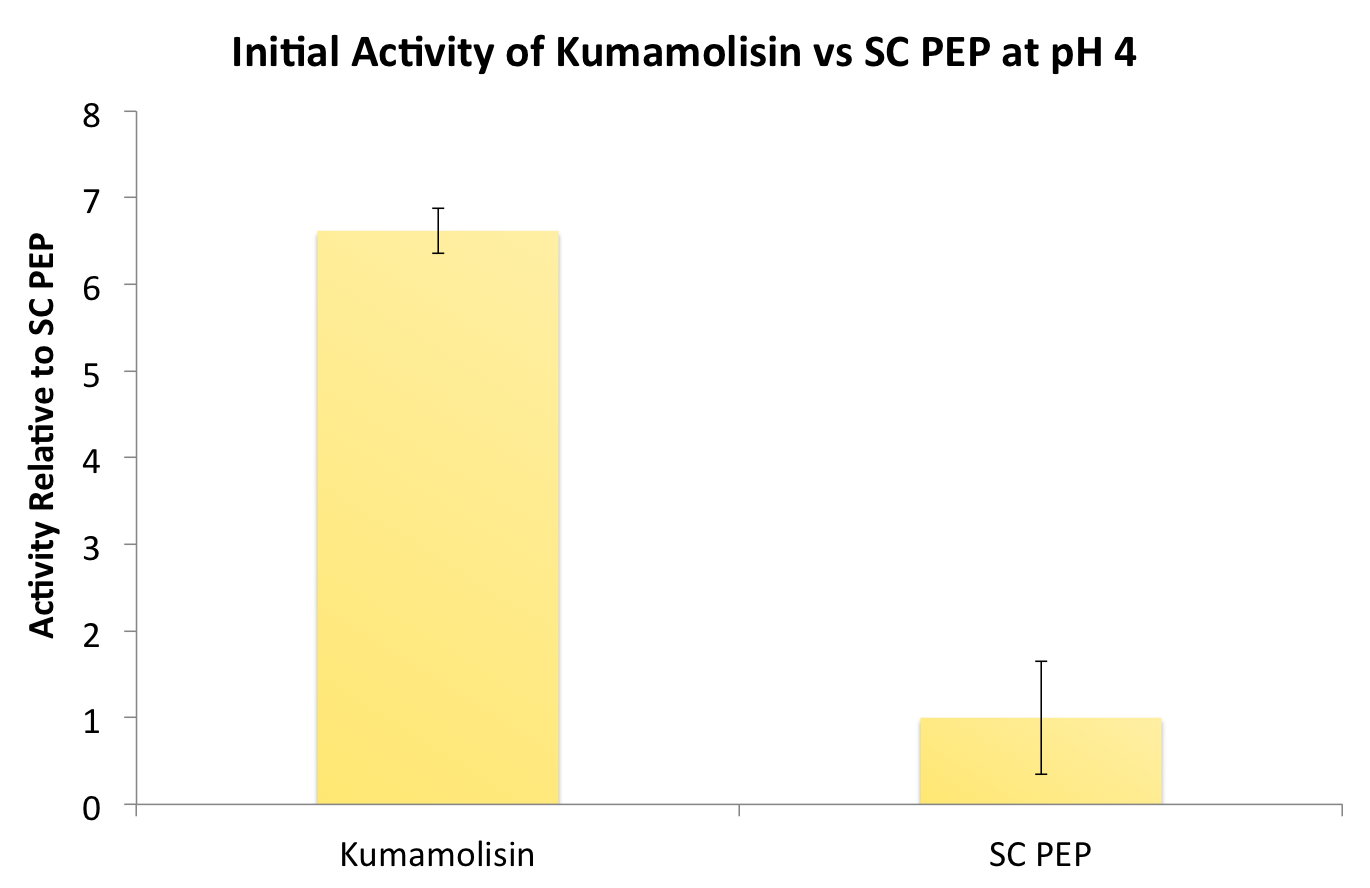

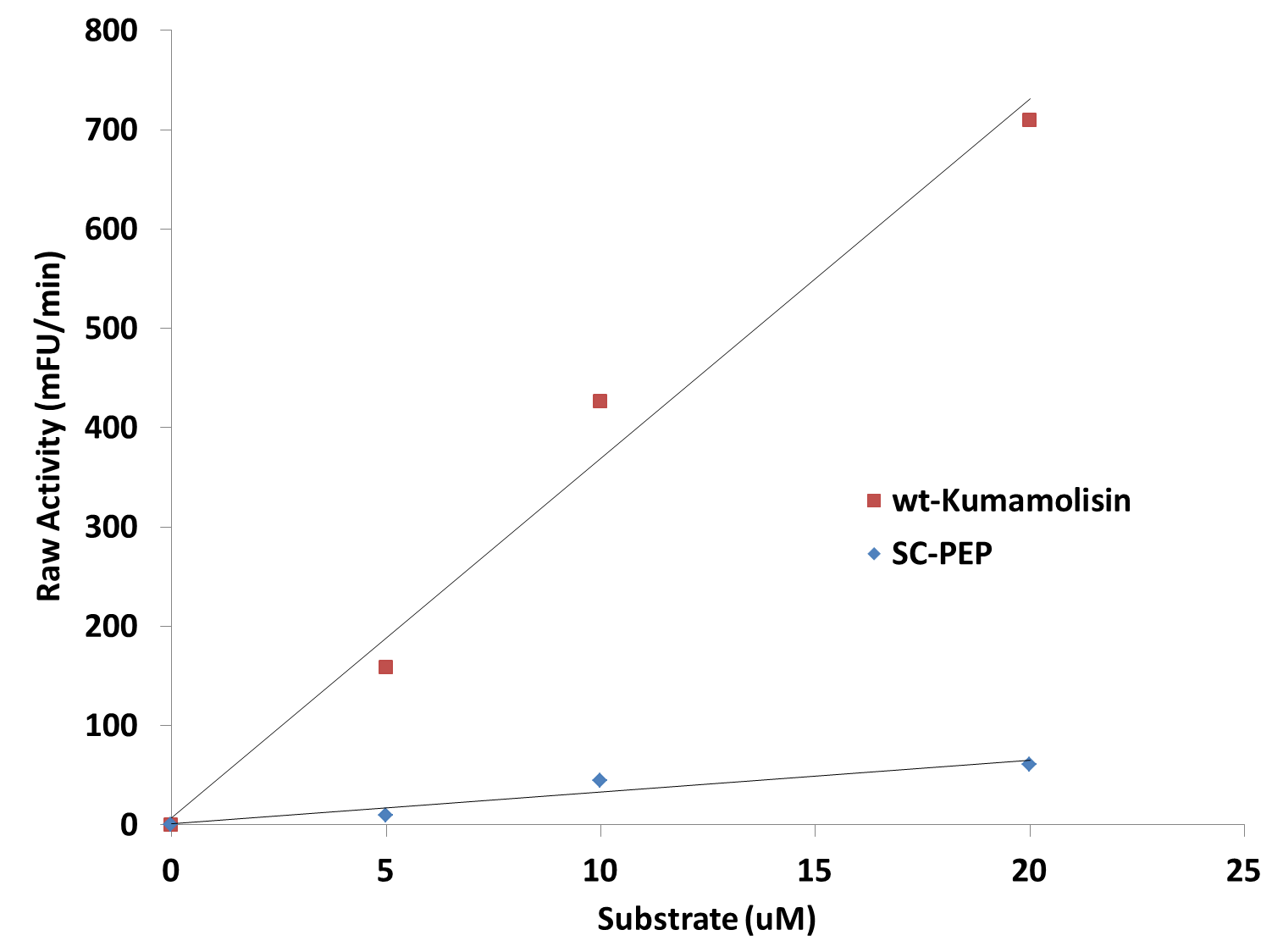

| - | After | + | After identifying Kumamolisin as a good candidate for activity at low pH, we tested its activity on breaking down PQLP at pH 4 against the activity of SC PEP, the enzyme currently in clinical trials for breaking down gluten. Kumamolisin had never been tested for its ability to breakdown gluten, and so we began novel experimentation into the enzyme's activity on our gluten model. From tests using the fluorescent PQLP system described in our methods section, Kumamolisin showed about 7 times better activity on breaking down PQLP at pH 4 when compared to the activity of SC PEP. |

| - | [[File:Washington InitialKumavSC.png|center|500px|thumb|Initial screenings revealed that | + | [[File:Washington InitialKumavSC.png|center|500px|thumb|Initial screenings revealed that Kumamolisin has a much higher activity level than SC-PEP, in addition to being amenable to engineering and effective at gastric pH.]] |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 23: | Line 16: | ||

=='''Using a whole cell lysate assay to screen a large number of mutants for good activity'''== | =='''Using a whole cell lysate assay to screen a large number of mutants for good activity'''== | ||

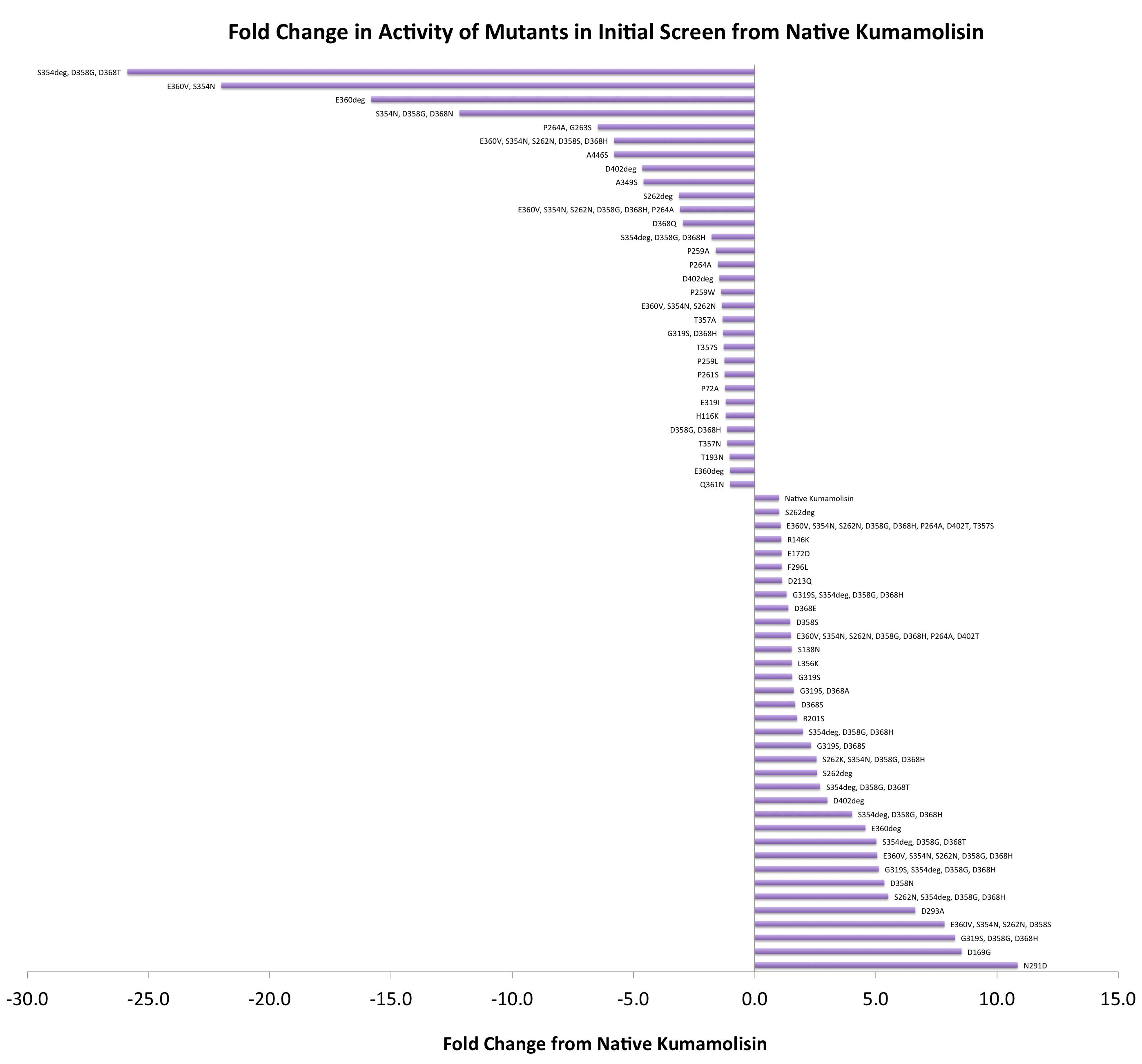

| - | In order to determine whether our proposed mutations to the wild-type Kumamolisin improved the ability of the enzyme to break down PQLP, we | + | In order to determine whether our proposed mutations to the wild-type Kumamolisin improved the ability of the enzyme to break down PQLP, we screened each mutant with a whole cell lysate fluorescence assay. Cells harboring the expressed mutants were lysed and the assay was performed at pH 4, mimicking the gastric environment. The released enzymes, after being roughly separated from cell material, were added to a fluorescent PQLP that had been conjugated to a quencher. Thus, no fluorescence was achieved until the peptide had been cleaved and the fluorophore had been released from the quencher. This allowed a relative assessment of rate of enzyme activity by measuring increase in fluorescence of the system. |

| - | As one might expect, our first screen of mutants showed some mutants with a decrease in activity from the wild-type, some showed no change, and some actually showed great increase in activity. One single point mutant showed | + | As one might expect, our first screen of mutants showed some mutants with a decrease in activity from the wild-type, some showed no change, and some actually showed great increase in activity. One single point mutant showed over 10-fold increase in activity from wild-type Kumamolisin! |

| - | + | [[File:Washington Vertical Initial Screen.png|center|700px|thumb|Over 100 unique mutants were screened with a whole cell lysate assay for improved activity on the PQLP model substrate. *"deg" in the data labels indicates use of a degenerate primer. Data for these points is representative of a group of variants, each with different substitutions at one residue. This accounts for the <100 data points on this graph, despite testing >100 novel mutants in total.]] | |

| - | [[File:Washington | + | |

=='''Purifying and characterizing promising mutants for accurate rate comparison'''== | =='''Purifying and characterizing promising mutants for accurate rate comparison'''== | ||

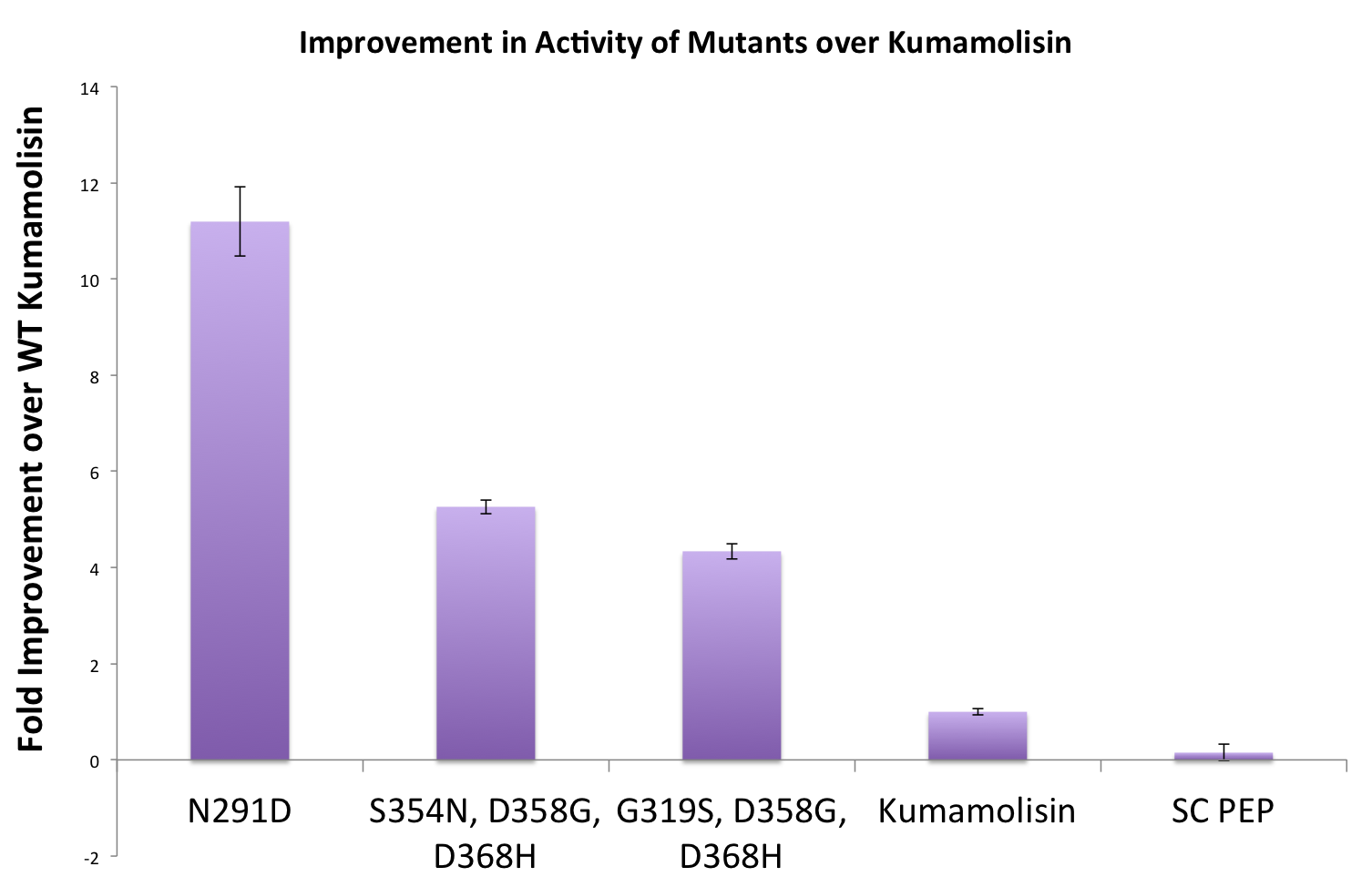

| - | Once we had identified mutants that showed a promising increase in activity from the wild-type | + | Once we had identified mutants that showed a promising increase in activity from the wild-type, we purified and characterized activity in concentration controlled fluorescence assays, identical to the fluorescence system used for the whole cell lysate assay. Our best mutant demonstrated an 11-fold increase in activity from the native enzyme. |

| - | [[File:Washington Best Mutants.png|center|500px|thumb| | + | [[File:Washington Best Mutants.png|center|500px|thumb|Concentration controlled rate data relative to native Kumamolisin for three of our most active mutants.]] |

---- | ---- | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | ='''Combining Mutations for the Construction of a Gluten Hydrolase'''= | |

| - | In order to achieve even more rate improvement from the native, we repeated our mutagenesis, this time taking successful mutations and adding them | + | In order to achieve even more rate improvement from the native, we repeated our mutagenesis, this time taking successful mutations and adding them together to make combinatorial variants. |

| + | =='''Successful mutations were combined to construct a second library for screening'''== | ||

| + | |||

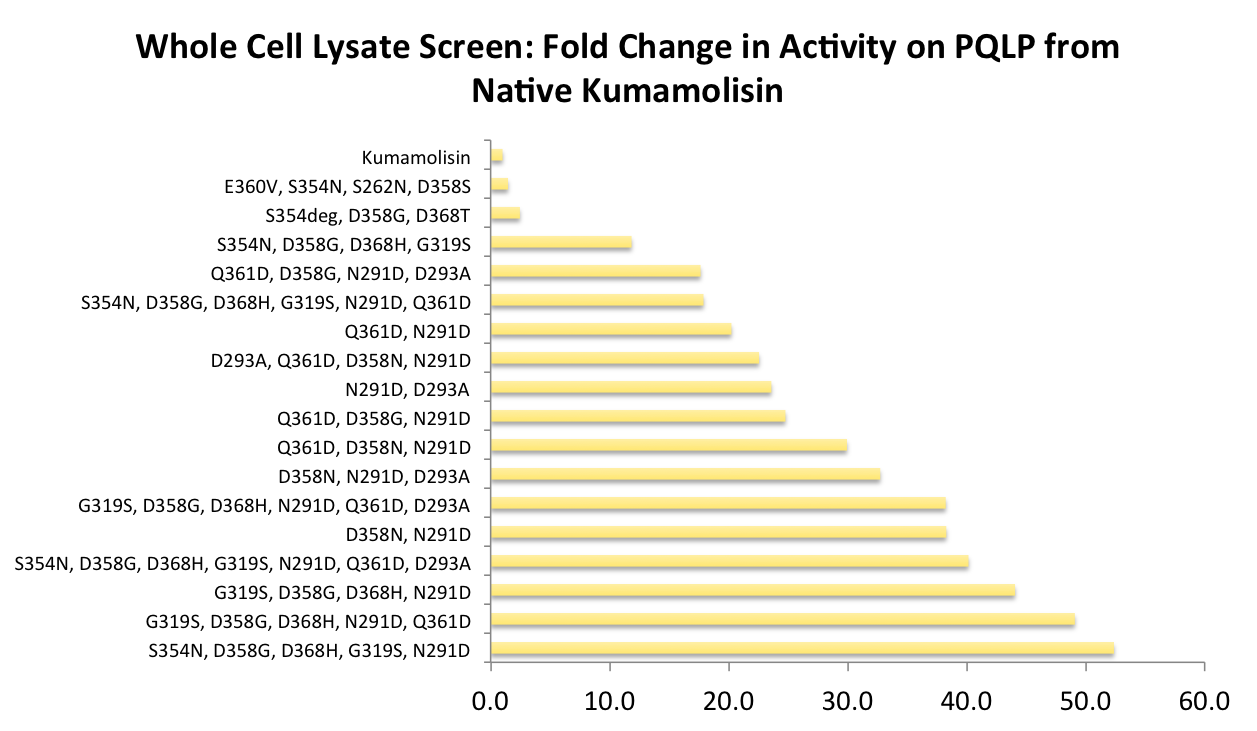

| + | After designing a collection of combinatorial mutants, drawing from successful mutations discovered in the first round, we again performed a rough screen to identify promising combinations of mutations. From the initial screen on our combinatorial mutants, it appeared that we had achieved around 50 times better activity than native Kumamolisin on breaking down PQLP. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Washington Comb Fold Change.png|center|500px|thumb|From initial whole cell lysate screens on combinatorial mutants, it appears that about 50-fold improvement over native Kumamolisin activity on PQLP has been achieved.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =='''One of the combinatorial mutants resulted in over a 100-fold increase in activity'''== | ||

| + | |||

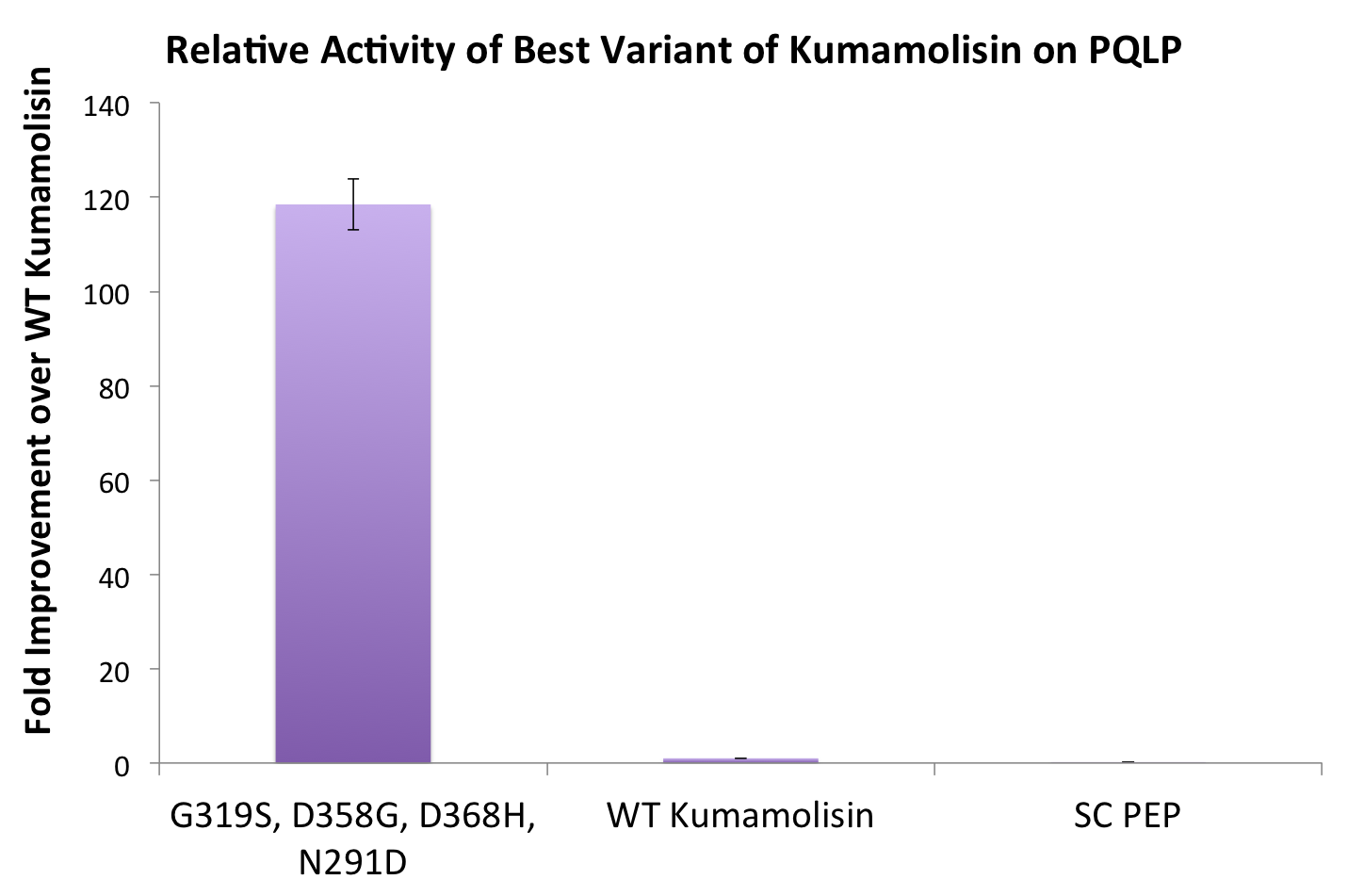

| + | By combining two of our top groups of mutations from the first round, we achieved an over 100-fold increase in activity on breaking down PQLP from the wild-type enzyme. This variant enzyme is ultimately 784 times better at breaking down PQLP than SC PEP, the enzyme currently in clinical trials for treating gluten intolerance. | ||

[[File:Washington BestCombMutant.png|center|500px|thumb|Our final engineered enzyme showed activity over 100 fold higher than wild type Kumamolisin, and ~700 fold higher than SC-PEP.]] | [[File:Washington BestCombMutant.png|center|500px|thumb|Our final engineered enzyme showed activity over 100 fold higher than wild type Kumamolisin, and ~700 fold higher than SC-PEP.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =='''Calculating the catalytic efficiency'''== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Washington_Linear_Michaelis_Celiac.png|right|450px|thumb|Activity vs. substrate graph shows assays were done at substrate levels where the Michaelis-Menten curve is linear. R<sup>2</sup> values were greater 0.9 for both lines of best fit.]] | ||

| + | {| {{table}} | ||

| + | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''Mutation(s)''' | ||

| + | | align="center" style="background:#f0f0f0;"|'''''k<sub>cat</sub>''/''K<sub>M</sub>'' (M<sup>-1</sup> s<sup>-1</sup>)''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590023 '''N291D''']||(5.21 ± 0.11) x 10<sup>5</sup> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590024 '''S354N, D358G, D368H''']||(2.45 ± 0.02) x 10<sup>5</sup> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590022 '''G319S, D358G, D368H''']||(2.02 ± 0.02) x 10<sup>5</sup> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590087 '''G319S, D358G, D368H, N291D (KumaMax)''']||(3.86 ± 0.04) x 10<sup>6</sup> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590021 '''wt-Kumamolisin''']||(3.25 ± 0.05) x 10<sup>4</sup> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | SC-PEP ||(4.96 ± 0.75) x 10<sup>3</sup> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Since we were able to measure the activity of these mutants at substrate and enzyme concentrations corresponding to the linear portion of a Michaelis-Menten curve, we were also able to calculate the catalytic efficiency (''k<sub>cat</sub>''/''K<sub>M</sub>'') values for wt-Kumamolisin, SC-PEP, and a few of our best mutants. This was done by first converting the raw activity in milli-Fluorescent Units (mFU)/min to the observed velocity (V<sub>obs</sub>) in M/min using a conversion constant with units of mFU/M. Since the concentration of total substrate and enzyme in each case was known, we were then able to use the equation (''k<sub>cat</sub>''/''K<sub>M</sub>'') = V<sub>obs</sub>/([E][S]), derived from the Michaelis-Menten equation, to calculate the catalytic efficiency of each mutant enzyme of interest. We were not, however, able to measure the independent catalytic (''k<sub>cat</sub>'') and binding constants (''K<sub>M</sub>'') using this methodology. Thus, one of our priorities moving forward will be to develop a mass spectroscopy assay to determine these constants independently. | ||

Latest revision as of 23:53, 28 October 2011

Testing Kumamolisin-As against SC-PEP

After identifying Kumamolisin as a good candidate for activity at low pH, we tested its activity on breaking down PQLP at pH 4 against the activity of SC PEP, the enzyme currently in clinical trials for breaking down gluten. Kumamolisin had never been tested for its ability to breakdown gluten, and so we began novel experimentation into the enzyme's activity on our gluten model. From tests using the fluorescent PQLP system described in our methods section, Kumamolisin showed about 7 times better activity on breaking down PQLP at pH 4 when compared to the activity of SC PEP.

Testing mutants for activity on breaking down PQLP

Using a whole cell lysate assay to screen a large number of mutants for good activity

In order to determine whether our proposed mutations to the wild-type Kumamolisin improved the ability of the enzyme to break down PQLP, we screened each mutant with a whole cell lysate fluorescence assay. Cells harboring the expressed mutants were lysed and the assay was performed at pH 4, mimicking the gastric environment. The released enzymes, after being roughly separated from cell material, were added to a fluorescent PQLP that had been conjugated to a quencher. Thus, no fluorescence was achieved until the peptide had been cleaved and the fluorophore had been released from the quencher. This allowed a relative assessment of rate of enzyme activity by measuring increase in fluorescence of the system.

As one might expect, our first screen of mutants showed some mutants with a decrease in activity from the wild-type, some showed no change, and some actually showed great increase in activity. One single point mutant showed over 10-fold increase in activity from wild-type Kumamolisin!

Purifying and characterizing promising mutants for accurate rate comparison

Once we had identified mutants that showed a promising increase in activity from the wild-type, we purified and characterized activity in concentration controlled fluorescence assays, identical to the fluorescence system used for the whole cell lysate assay. Our best mutant demonstrated an 11-fold increase in activity from the native enzyme.

Combining Mutations for the Construction of a Gluten Hydrolase

In order to achieve even more rate improvement from the native, we repeated our mutagenesis, this time taking successful mutations and adding them together to make combinatorial variants.

Successful mutations were combined to construct a second library for screening

After designing a collection of combinatorial mutants, drawing from successful mutations discovered in the first round, we again performed a rough screen to identify promising combinations of mutations. From the initial screen on our combinatorial mutants, it appeared that we had achieved around 50 times better activity than native Kumamolisin on breaking down PQLP.

One of the combinatorial mutants resulted in over a 100-fold increase in activity

By combining two of our top groups of mutations from the first round, we achieved an over 100-fold increase in activity on breaking down PQLP from the wild-type enzyme. This variant enzyme is ultimately 784 times better at breaking down PQLP than SC PEP, the enzyme currently in clinical trials for treating gluten intolerance.

Calculating the catalytic efficiency

| Mutation(s) | kcat/KM (M-1 s-1) |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590023 N291D] | (5.21 ± 0.11) x 105 |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590024 S354N, D358G, D368H] | (2.45 ± 0.02) x 105 |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590022 G319S, D358G, D368H] | (2.02 ± 0.02) x 105 |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590087 G319S, D358G, D368H, N291D (KumaMax)] | (3.86 ± 0.04) x 106 |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K590021 wt-Kumamolisin] | (3.25 ± 0.05) x 104 |

| SC-PEP | (4.96 ± 0.75) x 103 |

Since we were able to measure the activity of these mutants at substrate and enzyme concentrations corresponding to the linear portion of a Michaelis-Menten curve, we were also able to calculate the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) values for wt-Kumamolisin, SC-PEP, and a few of our best mutants. This was done by first converting the raw activity in milli-Fluorescent Units (mFU)/min to the observed velocity (Vobs) in M/min using a conversion constant with units of mFU/M. Since the concentration of total substrate and enzyme in each case was known, we were then able to use the equation (kcat/KM) = Vobs/([E][S]), derived from the Michaelis-Menten equation, to calculate the catalytic efficiency of each mutant enzyme of interest. We were not, however, able to measure the independent catalytic (kcat) and binding constants (KM) using this methodology. Thus, one of our priorities moving forward will be to develop a mass spectroscopy assay to determine these constants independently.

"

"