Team:Washington/Celiacs/Methods

From 2011.igem.org

(→Using Foldit to Design Mutations) |

(→Redesigning Kumamolisin to Have Higher Activity at Low pH) |

||

| (55 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| - | + | <center><big><big><big><big>'''Gluten Destruction: Methods'''</big></big></big></big></center><br><br> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ==Using Foldit to Design Mutations== | + | ='''Redesigning Kumamolisin to Have Higher Activity at Low pH'''= |

| - | In order to design mutations to wild-type Kumamolisin that would increase the enzyme’s proteolytic activity on gluten, we used a computational enzyme editing program called Foldit, which allows the user to hypothetically modify the amino acid sequence of a protein by creating point mutations at any location within the protein’s crystal structure. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Washington Foldit.png|550px|thumb|right|A Sample Mutation in [http://fold.it Foldit] Showing a Change from Glycine to Serine]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =='''Using [http://fold.it Foldit] to Design Mutations'''== | ||

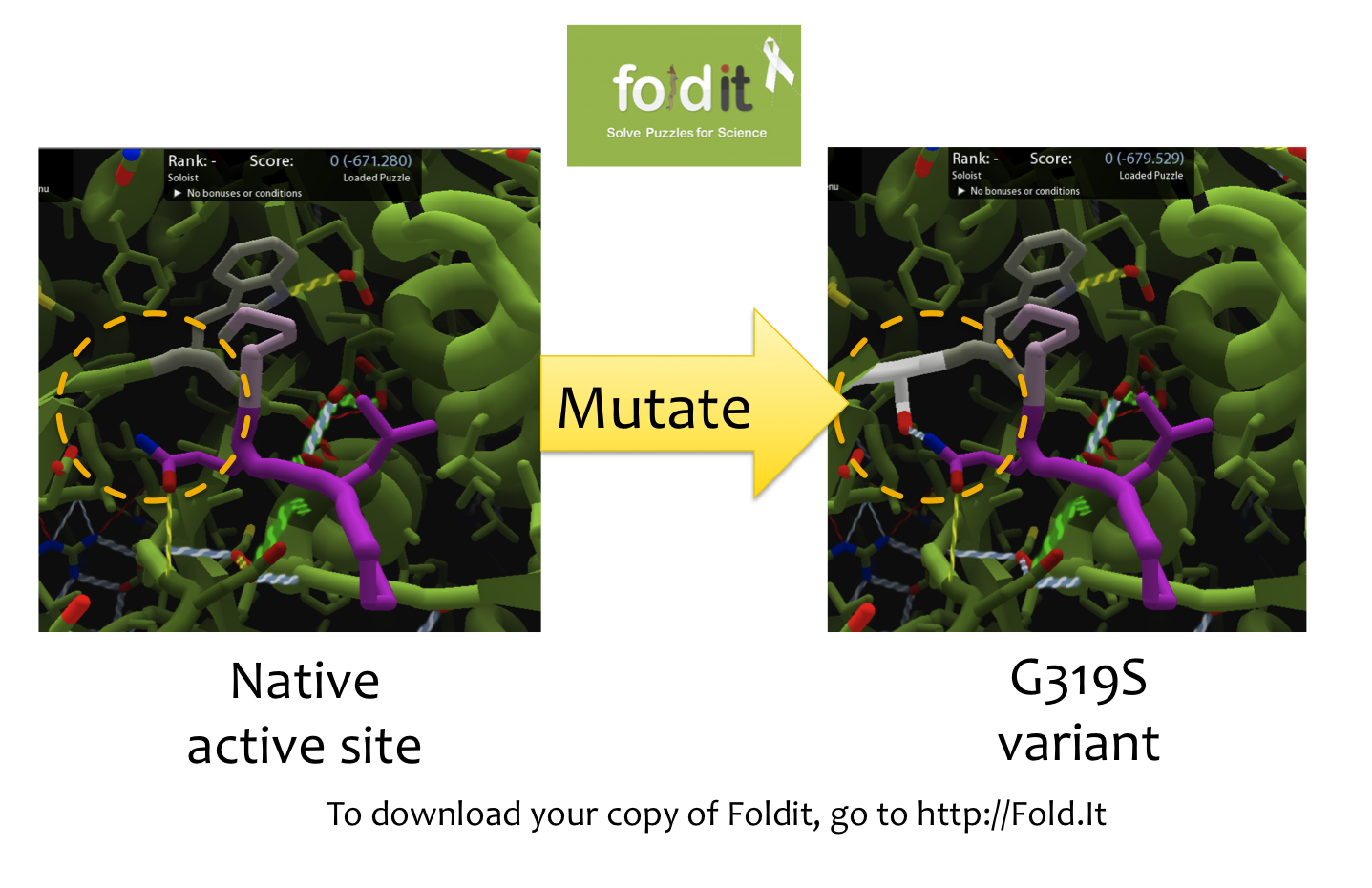

| + | In order to design mutations to wild-type Kumamolisin that would increase the enzyme’s proteolytic activity on gluten, we used a computational enzyme editing program called [http://fold.it Foldit], which allows the user to hypothetically modify the amino acid sequence of a protein by creating point mutations at any location within the protein’s crystal structure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Within Foldit, we loaded Kumamolisin’s crystal structure in complex with a model PQLP peptide that recurs frequently in gluten, thus mimicking gluten as a substrate. We then modified the amino acid residues around the active site of Kumamolisin in the crystal structure, attempting to decrease the free energy of, and thus stabilize, the system. Estimations of free energy were based on algorithms run by Foldit. | ||

Using this method, we designed over 100 novel mutants, each of which could potentially increase Kumamolisin’s proteolytic activity on gluten. | Using this method, we designed over 100 novel mutants, each of which could potentially increase Kumamolisin’s proteolytic activity on gluten. | ||

| - | = | + | |

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | ='''Mutagenizing Kumamolisin'''= | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kunkel mutagenesis is a classic procedure for incorporating targeted mutations into a piece of DNA, so it was ideal for changing our wild-type Kumamolisin gene to code instead for specifically designed variant enzymes. | ||

[[File:Washington Kunkels.png|500px|thumb|left|Overview of how Kunkel Mutagenesis works]] | [[File:Washington Kunkels.png|500px|thumb|left|Overview of how Kunkel Mutagenesis works]] | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =='''Kunkel Mutagenesis'''== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first step to producing our specially designed enzymes was to change the wild-type gene that codes for Kumamolisin to code instead for variant enzymes with our desired amino acid substitutions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We designed mutagenic oligonucleotide primers that would anneal to the wild-type Kumamolisin gene and incorporate point mutations that, when expressed, would result in a variant of Kumamolisin with the desired amino acid shift. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To incorporate these mutations, we first isolated single stranded DNA (ssDNA) of our vector harboring the wild-type Kumamolisin gene. To do this we infected cells with bacteriophage M13, which packages its own ssDNA genome identified by length, and so in tandem packaged our vector in single stranded form. We then harvested the phage from the lysed culture of E. coli, and extracted our single stranded vector DNA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next, we annealed and extended our mutagenic oligos to incorporate the specified mutations into the newly synthesized antisense strand. This hybrid vector was transformed into E. coli that degraded the original uracil-containing DNA and replaced it with sections complementary to the mutagenized strand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| Line 32: | Line 55: | ||

| + | ='''Using a Whole Cell Lysate Assay to Test Activity of Mutants'''= | ||

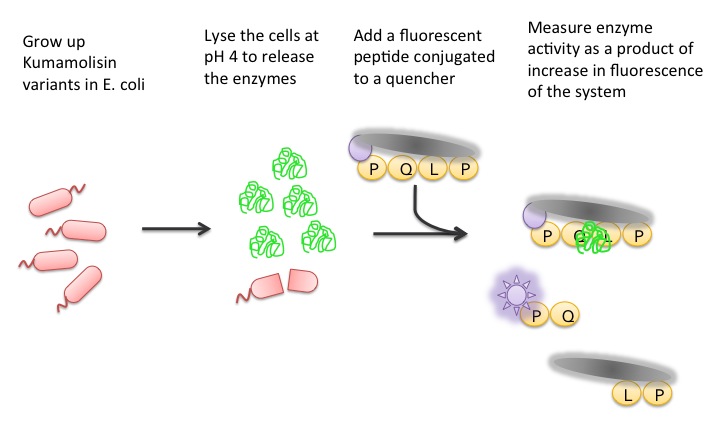

| + | To test our designs, we developed a whole cell lysate assay that allowed us to perform a rough screen of a large number of mutants. In this assay, we expressed our mutant enzymes in <i>E. coli</i>, lysed the cells and separated the enzymes from large cell particulate. We then performed the assay at pH 4, mimicking the gastric environment. We added our model PQLP peptide, conjugated to both a fluorophore and a quencher so that no fluorescence would be achieved until after the peptide had been enzymatically cleaved. We then measured the fluorescence of each reaction at 30 second intervals, and were thereby able to estimate relative activity on breaking down PQLP by increase in fluorescence of the system. | ||

| + | [[File:Washington Whole Cell Lysate Assay.jpg|center|General Overview of the Whole Cell Lysate]] | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | ='''Testing Purified Mutants to Accurately Assess Activity'''= | ||

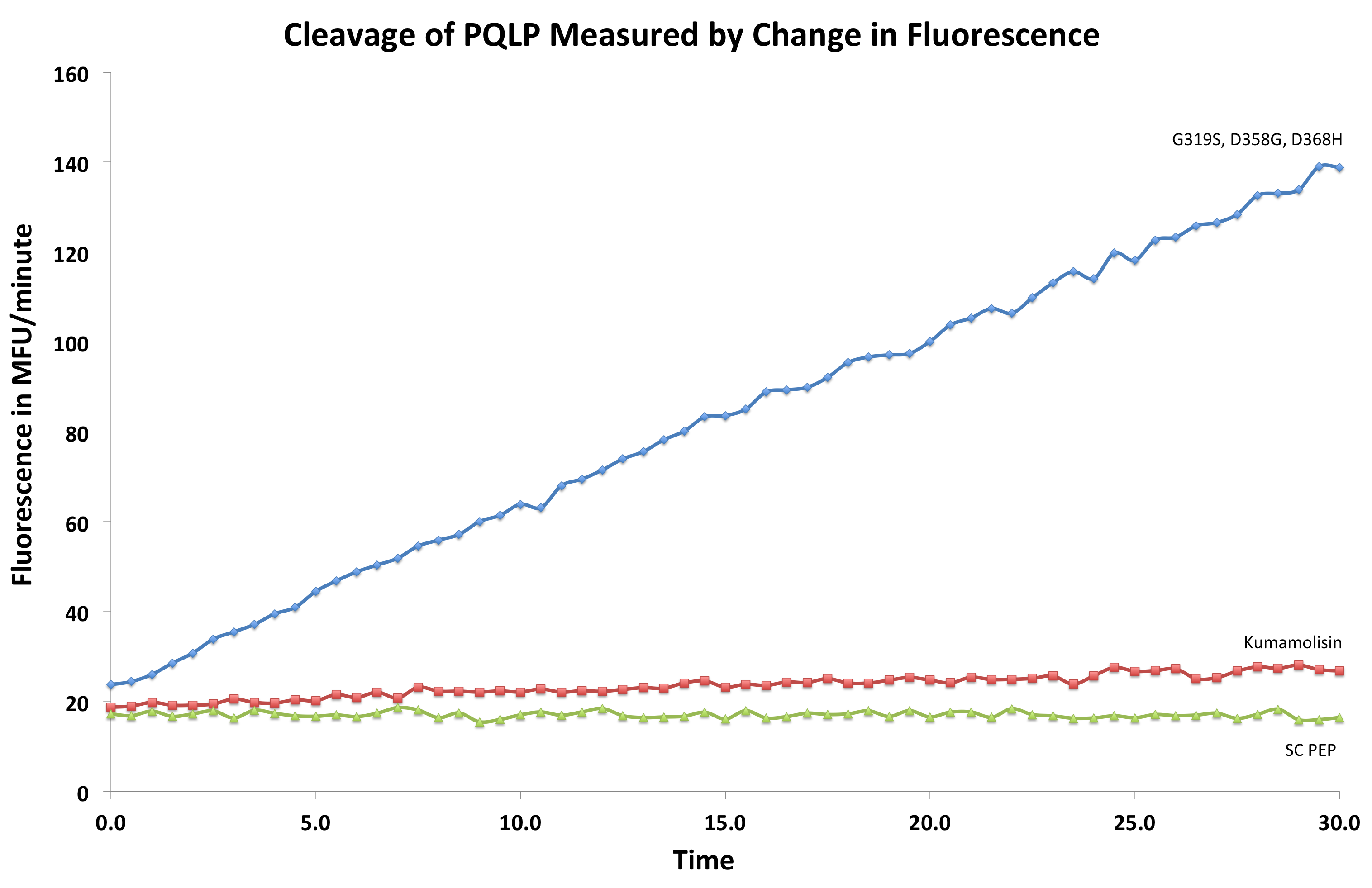

| + | [[File:Washington First Raw Data.png|right|500px|thumb|We measured fluorescence of each reaction at 30 second intervals to see the rate at which each mutant cleaved PQLP.]] | ||

| + | =='''Purification'''== | ||

| + | From our whole cell lysate screen of each design, we identified mutants that showed the most increase in activity from the wild-type Kumamolisin. We then proceeded to purify these most promising variants and test them against the wild-type and against SC PEP using the same fluorescence metric designed for the whole cell lysate assay. The key difference between the whole cell assay and the purified protein assay is that in the latter we were able to control the concentration of enzyme in each well, adjusting for the possibility of varying expression levels and thus enzyme concentrations in the whole cell lysate assay. | ||

| - | + | Purification was performed via Nickel-affinity chromatography, and resulting protein concentrations were measured using ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | == | + | =='''Assay'''== |

| - | + | Concentration dependent assays were performed for each promising mutant. We measured the fluorescence of each reaction at 30 second intervals to see the rate at which fluorescence increased, thus obtaining a relative rate of cleavage of PQLP by increase in fluorescence of the system. Raw data appeared as shown right, and the slope of each line was calculated, giving us relative rate information that could be used in conjunction with rate information obtained in the same assay for native Kumamolisin to determine fold change in activity. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

Latest revision as of 02:36, 29 September 2011

Redesigning Kumamolisin to Have Higher Activity at Low pH

Using [http://fold.it Foldit] to Design Mutations

In order to design mutations to wild-type Kumamolisin that would increase the enzyme’s proteolytic activity on gluten, we used a computational enzyme editing program called [http://fold.it Foldit], which allows the user to hypothetically modify the amino acid sequence of a protein by creating point mutations at any location within the protein’s crystal structure.

Within Foldit, we loaded Kumamolisin’s crystal structure in complex with a model PQLP peptide that recurs frequently in gluten, thus mimicking gluten as a substrate. We then modified the amino acid residues around the active site of Kumamolisin in the crystal structure, attempting to decrease the free energy of, and thus stabilize, the system. Estimations of free energy were based on algorithms run by Foldit.

Using this method, we designed over 100 novel mutants, each of which could potentially increase Kumamolisin’s proteolytic activity on gluten.

Mutagenizing Kumamolisin

Kunkel mutagenesis is a classic procedure for incorporating targeted mutations into a piece of DNA, so it was ideal for changing our wild-type Kumamolisin gene to code instead for specifically designed variant enzymes.

Kunkel Mutagenesis

The first step to producing our specially designed enzymes was to change the wild-type gene that codes for Kumamolisin to code instead for variant enzymes with our desired amino acid substitutions.

We designed mutagenic oligonucleotide primers that would anneal to the wild-type Kumamolisin gene and incorporate point mutations that, when expressed, would result in a variant of Kumamolisin with the desired amino acid shift.

To incorporate these mutations, we first isolated single stranded DNA (ssDNA) of our vector harboring the wild-type Kumamolisin gene. To do this we infected cells with bacteriophage M13, which packages its own ssDNA genome identified by length, and so in tandem packaged our vector in single stranded form. We then harvested the phage from the lysed culture of E. coli, and extracted our single stranded vector DNA.

Next, we annealed and extended our mutagenic oligos to incorporate the specified mutations into the newly synthesized antisense strand. This hybrid vector was transformed into E. coli that degraded the original uracil-containing DNA and replaced it with sections complementary to the mutagenized strand.

Using a Whole Cell Lysate Assay to Test Activity of Mutants

To test our designs, we developed a whole cell lysate assay that allowed us to perform a rough screen of a large number of mutants. In this assay, we expressed our mutant enzymes in E. coli, lysed the cells and separated the enzymes from large cell particulate. We then performed the assay at pH 4, mimicking the gastric environment. We added our model PQLP peptide, conjugated to both a fluorophore and a quencher so that no fluorescence would be achieved until after the peptide had been enzymatically cleaved. We then measured the fluorescence of each reaction at 30 second intervals, and were thereby able to estimate relative activity on breaking down PQLP by increase in fluorescence of the system.

Testing Purified Mutants to Accurately Assess Activity

Purification

From our whole cell lysate screen of each design, we identified mutants that showed the most increase in activity from the wild-type Kumamolisin. We then proceeded to purify these most promising variants and test them against the wild-type and against SC PEP using the same fluorescence metric designed for the whole cell lysate assay. The key difference between the whole cell assay and the purified protein assay is that in the latter we were able to control the concentration of enzyme in each well, adjusting for the possibility of varying expression levels and thus enzyme concentrations in the whole cell lysate assay.

Purification was performed via Nickel-affinity chromatography, and resulting protein concentrations were measured using ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry.

Assay

Concentration dependent assays were performed for each promising mutant. We measured the fluorescence of each reaction at 30 second intervals to see the rate at which fluorescence increased, thus obtaining a relative rate of cleavage of PQLP by increase in fluorescence of the system. Raw data appeared as shown right, and the slope of each line was calculated, giving us relative rate information that could be used in conjunction with rate information obtained in the same assay for native Kumamolisin to determine fold change in activity.

"

"