Team:Glasgow/Control of Dispersal/Intro

From 2011.igem.org

Control of Dispersal- Use of Light

Back to Results

Light is a ubiquitous feature of nature; it is a fundamental aspect of life on Earth, from driving photosynthesis in plants to allowing sight in humans. It is also an indispensable tool in the engineering of biological pathways.

The DISColi project aims to capitalize on light in the control of circuits which allow the modular construction of valuable products. In contrast to other potential response-inducers, such as temperature or chemicals, light has the ability to be finely adjusted and target very specific areas at very high resolution (100 megapixels per square inch as demonstrated by UT Austin '05 Coliroid). Unlike chemicals such as arabinose, lactose, IPTG and x-gal which are commonly used to induce gene expression, light is a non-invasive option to precisely induce transcription of the desired gene without heavily stressing the cell.

The wide-ranging spectrum of wavelengths which constitute light offer innumerable possibilities to the user; it's responsibility of synthetic biology to provide the receptors to the scientific community. With a simple and inexpensive set-up including a light-source and a filter, one is capable of fine tuning which wavelength is used. In tandem with a variety of different light-dependent devices, this system allows for precise control over what the desired outcome will be. Light can also yield high resolution results, meaning an enhanced formation of 2D pictures and bio-photolithographic devices.

Latherin: Origin

Latherin is a surfactant protein with detergent like properties.

Latherin is a surfactant protein with detergent like properties.

Latherin was first isolated from the sweat of horses (Equus caballus). It was first described in the 1980s by John Beeley and David Eckersall, from the University of Glasgow.

Since being found in horse sweat, the protein has since been found in the salivary glands of several species of geographically separated equids. Sequence analysis has shown that it is a highly conserved protein.

Research has established the presence of latherin in the salivary glands, but has not found it in any other tissue.

Natural Function:

Of the three species of mammal that are known to thermoregulate by sweating, horses are unique in having sweat with such a high concentration of protein and low concentration of salt. Latherin is the most abundant protein found in horse sweat and is believed to be the cause of the foaming appearance of the sweat on exercising horses.Latherin has long been suspected to be involved in thermoregulation. The protein is absorbed readily at hydrophobic surfaces, allowing them to become wettable. It will also cause a reduction in water surface tension. This function is presumably linked to the protein’s ability to facilitate evaporation of sweat from the pelt.

Latherin has also been found in the saliva of several species of equids. Its proposed function here is to aid in the wetting of food, which in turn aids chewing and the ability of salivary enzymes to digest the food.

Structure Information

Sequence analysis shows that latherin is a member of the PLUNC (“Palate, Lung and Nasal Epithelium Clone”) family. PLUNC represents a family of proteins, originally discovered in human. Their function is not entirely clear, but it is believed they may function in the innate immune response in the airways.

Analysis has shown that latherin has an unusual amino acid composition. The total number of hydrophobic amino acids is abnormally high, with leucine representing a large proportion of his. In fact, almost one in four residues is leucine. This is also true of the protein huPLUNC1, which has already been shown to have antimicrobial activity.

Ranaspumin-2

Ranaspumin-2 is one of six proteins used by the tungara frog (Engystomops pustulosus, found in Central and South America) to form protein foam nests in which it deposits its eggs. Protein foams are relatively rare in biology, and in this case offer a biocompatible solution to incubation and protection from mechanical destruction, as well as anti-microbial properties.

Structure

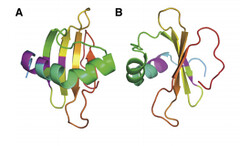

Coded for by the gene rsn-2, Ranaspumin-2 (Rsn2) is a monomeric surfactant protein, with an atomic mass of 11kDa. It has a molecular weight of 13415.2 and is comprised of 117 amino acids. In aqueous solution it adopts a tightly folded globular shape, which is uncharacteristic of surfactant proteins. In this 3D arrangement Rsn2 consists of a single helix over a four-stranded sheet, as can be seen in the image below.

Image 1: Ribbons structure of Ranaspumin-2 A: Frontal view B: 90 degree-rotation (Mackenzie, 2009)

This structure is highly unusual for a protein with surfactant properties, and appears to convey no significant amphiphilicity. It is therefore believed that Rsn2 undergoes a significant conformational change when at the air-water interface, in which it will expose hydrophobic groups to the air and hydrophilic groups to the water beneath. (Mackenzie, 2009)

Click here for Ranaspumin-2 sequence.Function

The protein undergoes a conformational refolding whilst in solution, exhibiting significant surfactant properties at the air-water interface. This property makes it potentially useful when working with biofilms that form at the same phase interface, as it is thought that it may assist in the destruction of the biofilm.

Click here for Dispersal Results

References & Further Reading:

Beegley J, et al., 1986. Isolation and characterization of latherin, a surface-active protein from horse sweat.Mcdonald R., et al., 2009. Latherin: A Surfactant Protein of Horse Sweat and Saliva

Kennedy M., Latherin: A Surface Active Protein from Horse Sweat

Kennedy M., 2011., Latherin and other biocompatible surfactant proteins

Goubran Botros H., et al 2001., Biochemical Characterisation and Surfactant Properties of Horse Allergens

Mackenzie et al., 2009. Ranaspumin-2: structure and function of a surfactant protein from the foam nests of a tropical frog. Biophysical Journal, 96, pp. 4984-4992

Kennedy, M.W., Proteins of Frog Foam Nests.

Cooper, A., Biofoams and natural protein surfactants

"

"