Team:DTU-Denmark/Project testing sRNA

From 2011.igem.org

Experiment: Testing sRNA

Contents |

Motivation

The biological experiments of the testing sRNA part is a proof of concept, showing that the E. coli sRNA sroB and the intergenic sRNA (trap-RNA) in the chbBCARG gene can be used to control gene expression by targeting the ybfM Shine-Dalgarno, and that these sRNAs can be rationally designed to target other Shine-Dalgarno sequences. The purpose is two-fold to construct plasmids and strains with deletions.

Strain construction involves deleting the original genes from the chromosome of a E. coli W3110 strain. Since we use the original genes, these need to be deleted from the chromosome to prevent them from interfering with our measurements.

Construction of plasmids necessary for testing our system involves taking the native system from E. coli, as well as a slightly modified system and putting them into plasmids that let us both control the expression of these components and measure the output of the system.

Strain construction

The strains used in testing our system were: IG9 a E. coli based on the wild-type K-12[3] strain W3110 with the lacZYA, chbBCARG operons deleted, and IG302 which is the K-12 $\Delta$lacZYA, $\Delta$chiP (alias ybfM), $\Delta$chiX (alias sroB, micM) strain constructed by Rasmussen et al.[6].

chbBCARG, chiP and chiX code for utilization of chitobiose (a sugar), chitobiose permease and the regulation of the chitobiose permease respectively.

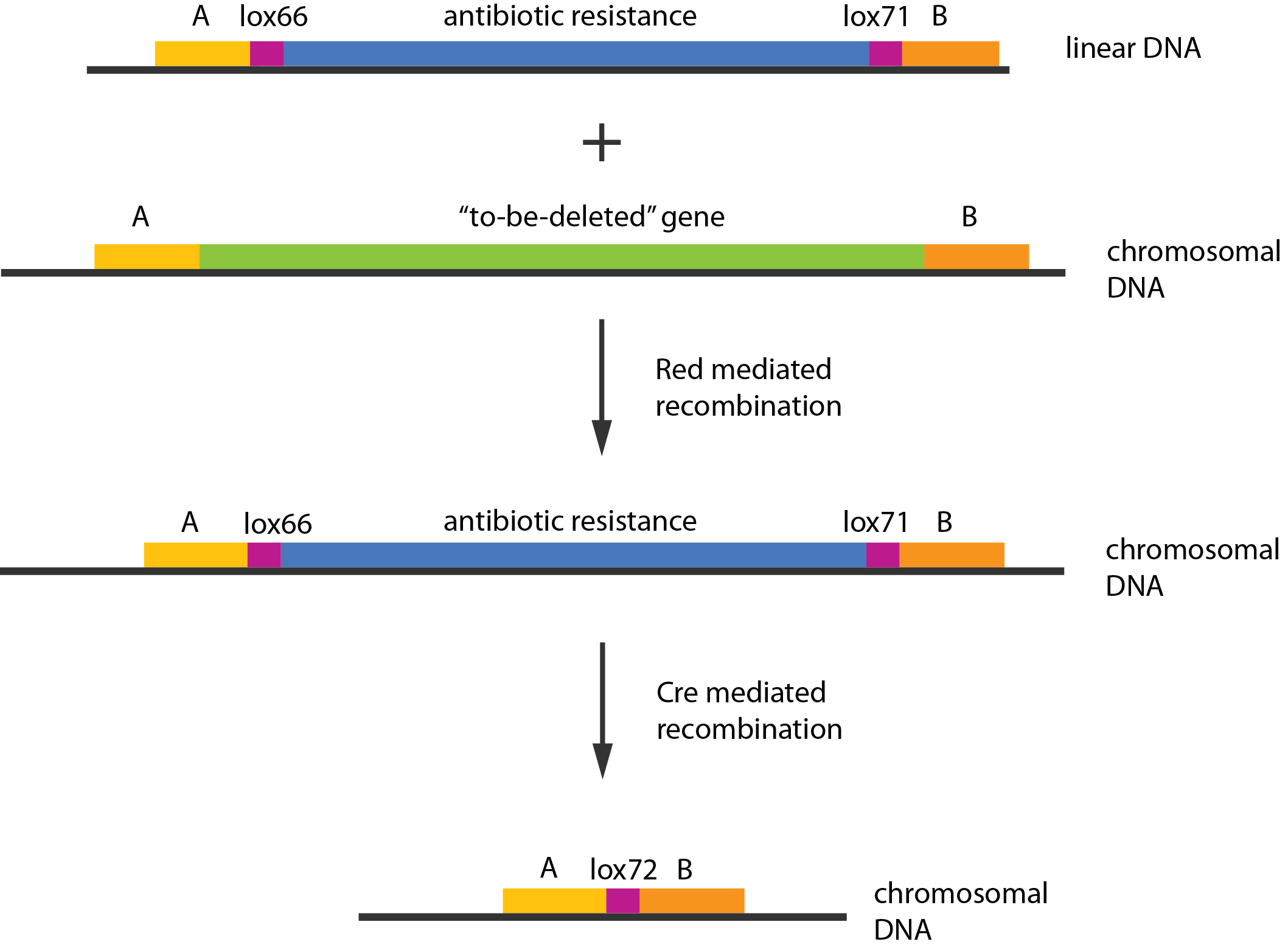

We used recombineering[1] to delete these genes. Schematically the procedure works in the following manner:

- Transform competent cells with Red and Cre helper plasmids.

- Make the cells competent and induce the Red recombination system.

- Transform with linear piece of DNA.

- Select for gain of resistance.

- Do colony PCR to check that resistance gene is inserted in the correct place.

- Move to medium inducing the Cre recombinase.

- Screen for loss of resistance.

- Verify the construct by colony PCR.

- Repeat step 2-7 as needed.

- Cure the helper plasmids.

The Red helper plasmids encodes the $\lambda{}$ phage Red recombination system. This system allows recombination events between sequences with around 40 nucleotides of homology. The cre helper plasmid encodes the Cre recombinase. This recombinase recognises 34bp loxP sequences and promotes recombination between them.

An example of a linear piece of DNA that could be used with this method, as well as the simplified representation of the procedure, can be seen in figure:

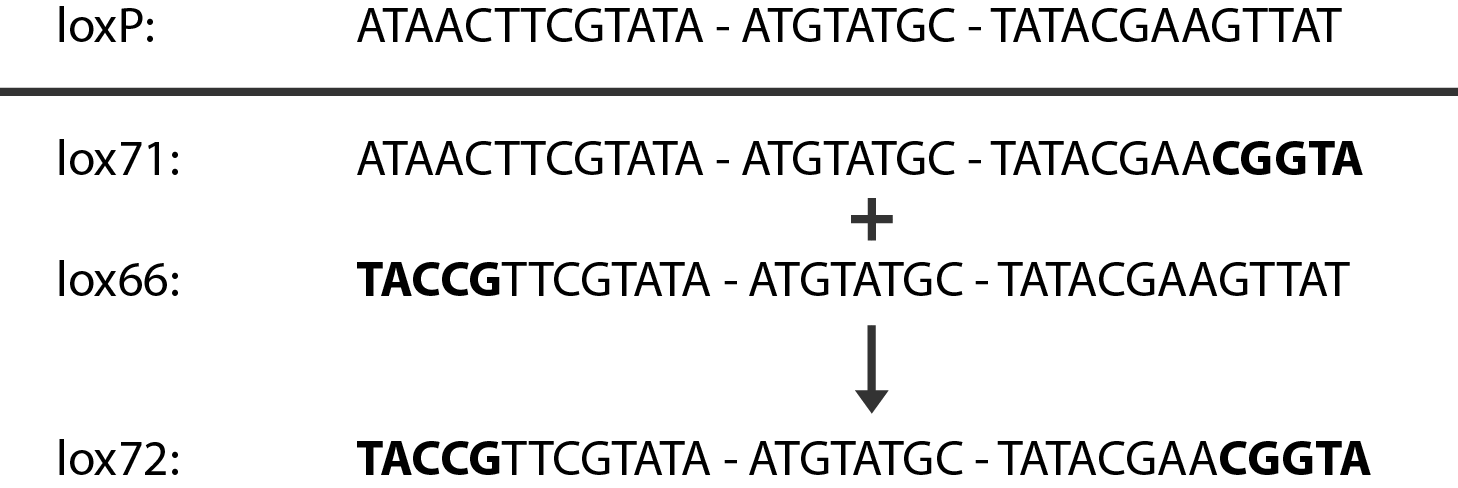

In case of two or more subsequent gene deletions using Red-Cre recombineering a problem of recombination between an old loxP site and newly introduced ones arises. Remember, that after each round of redswap one loxP site is left in the genome. As a result recombination using Cre recombinase in second or next redswap might not occur between loxP sites flanking a resistance gene. To circumvent this problem two mutated loxP sequences are used - lox66 and lox71[4]. In spite of the mutations these lox sites are recognized by Cre which can remove the intervening region. Finally, from lox66 and lox71 a new site is formed, lox72, which has a reduced affinity to Cre recombinase. Thus, more than one gene deletions can be subsequently conducted.

Construction of plasmids

In order to quantitatively describe the natural trap-RNA system the following four plasmids were constructed:

- PchiP-lacZ plasmid

- To mimic and test repression of the chiP gene its upstream region of 599 bp was fused to reporter genes lacZ and inserted on the pSB1C3 plasmid. Expression from PchiP promoter is costitutive however it can be induced to a higher level by chitobiose. LacZ codes for $\beta$-galactosidase and its activity was tested using $\beta$-Gal assays.

- PchiP(mutated)-lacZ plasmid

- This plasmid is similar to the PchiP-lacZ plasmid, except the Shine-Dalgarno has been changed. This is expected to abolish or limit the regulatory effect of chiX.

- Ptet-chiX plasmid

- ChiX which is 84 bp long and regulates the wild-type chiP Shine-Dalgarno[2][5], was inserted into pSB4K under the control of the inducible promoter Ptet. Expression from Ptet promoter was induced using anhydrotetracycline.

- PBAD-chiXR plasmid

- A 284 bp long introgenic region from chbBCARG operon known to regulate chiX[2][5] was inserted into pSB3T5 plasmid. Expression from that plasmid was controlled by regulatory element from ara operon with arabinose as inducer.

Details on how the plasmids were constructed, including information on primers used, can be found in lab notebook.

Verifying constructs

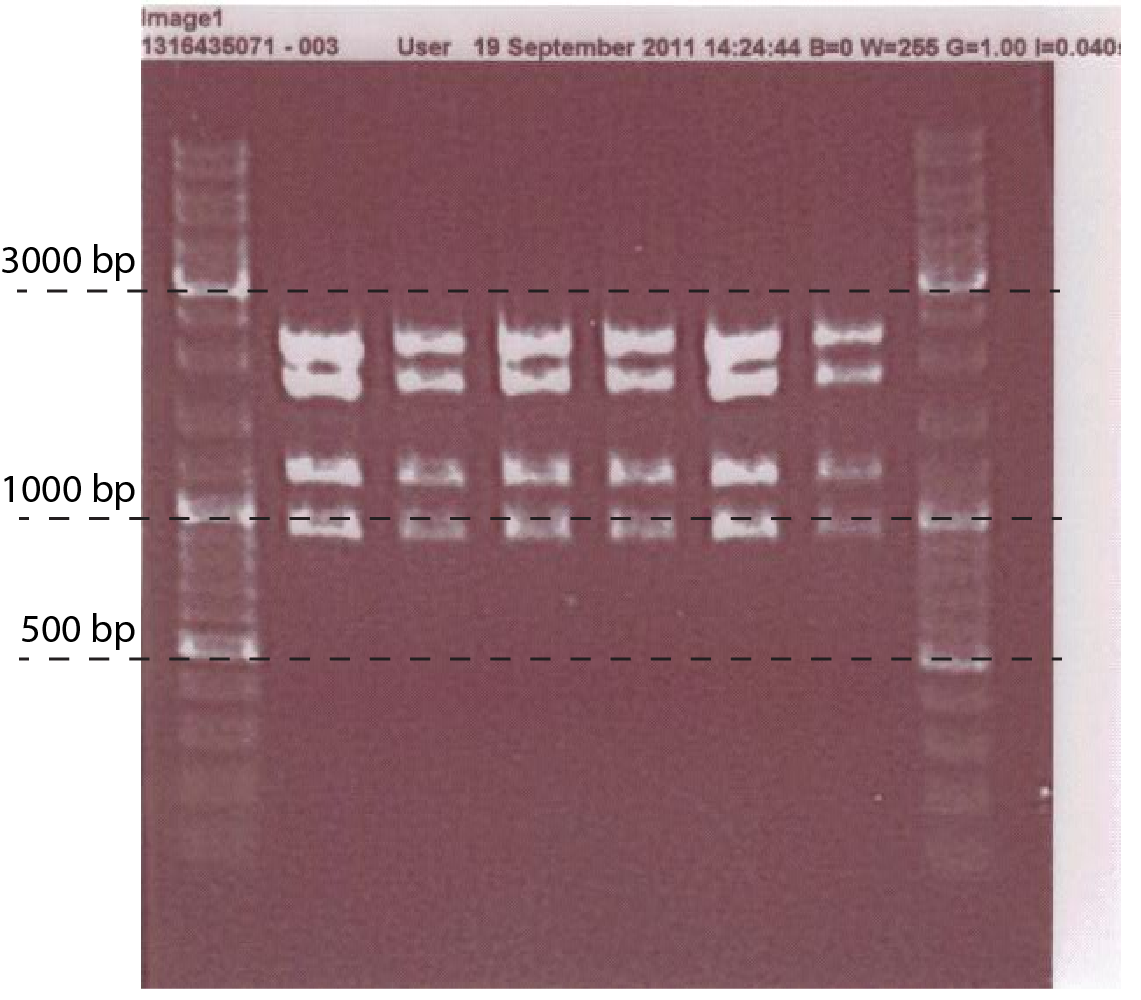

The plasmids we constructed were verified in two ways. The PBAD-chiXR fusion and PchiP-lacZ fusion were tested by restriction analysis of the plasmid. And the Ptet-chiX fusion was tested by PCR.

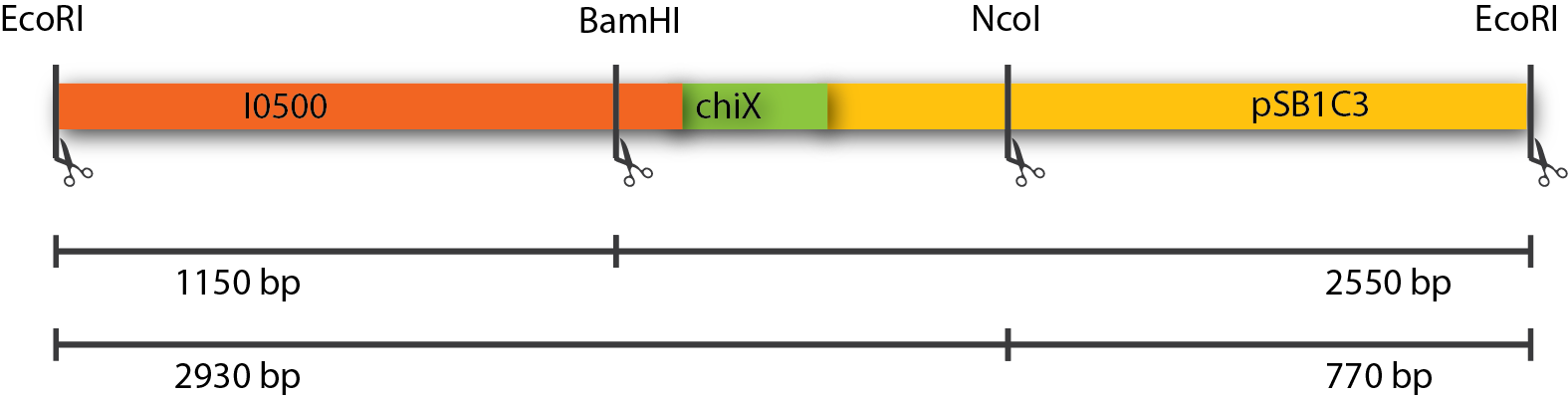

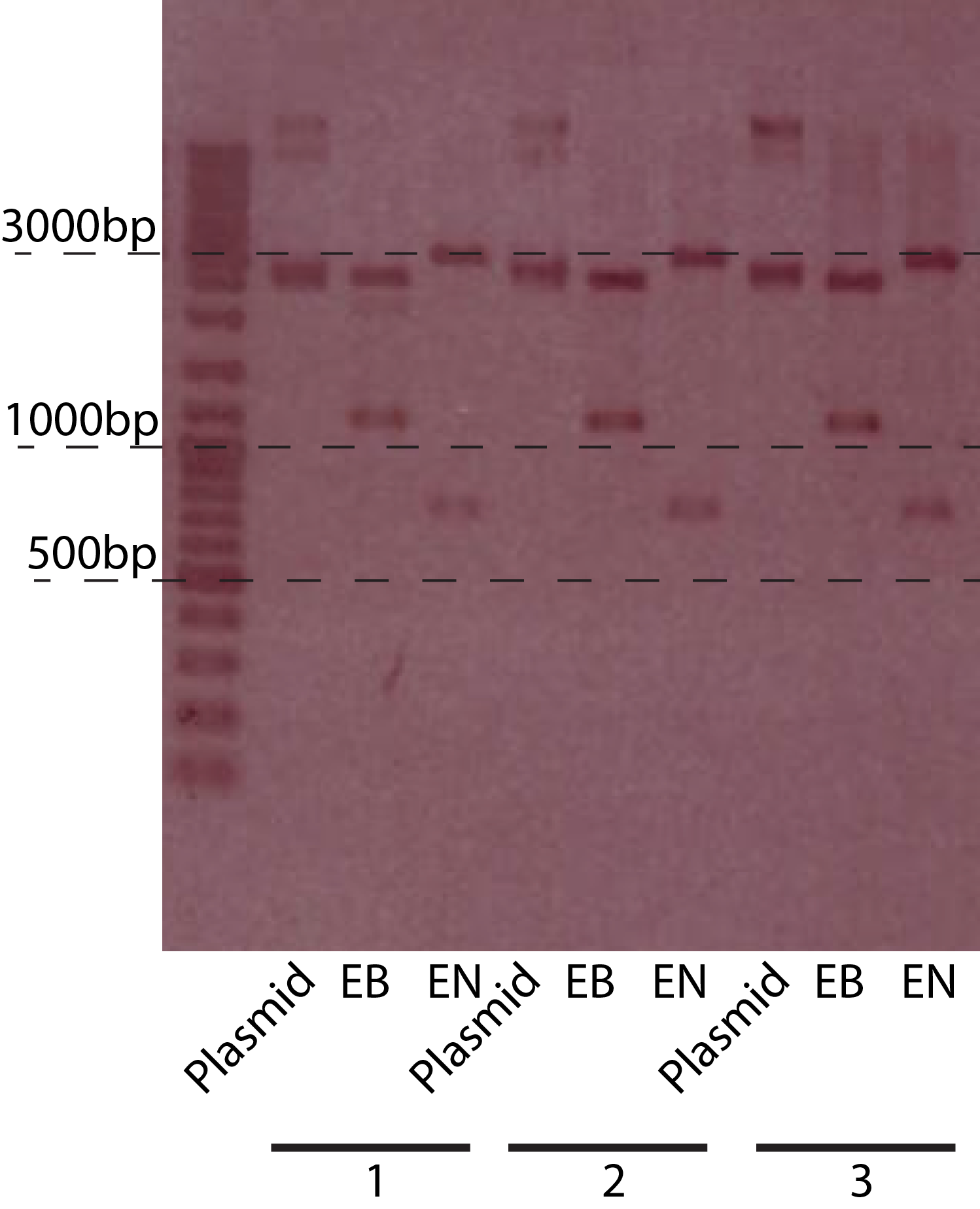

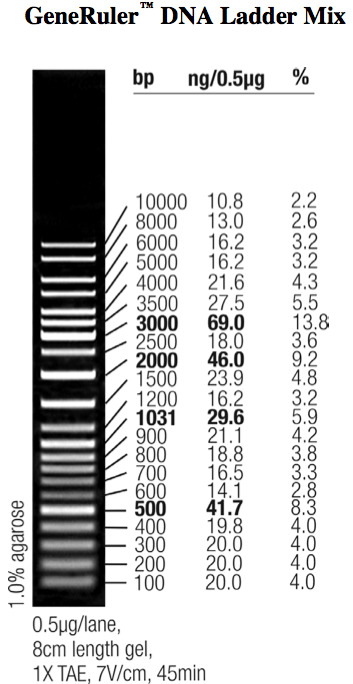

The restriction of three plasmids tested revealed fragments of the expected sizes. These can be seen in the table below. The gel picture is also available.

| Restriction Enzymes | Expected sizes |

|---|---|

| EcoRI + BamHI | 1150 + 2550 |

| EcoRI + NcoI | 2930 + 770 |

The PCR to test the Ptet-chiX fusion was done on a number of colonies following a transformation. The primers used were CS149 (GGTTTGCCACCTGACGTCTAAGAA) and CS150 (CCAAATTACCGCCTTTGAGTG). These two primers anneal just outside the BioBrick and can be used to PCR any BioBrick in a BioBrick compatible plasmid. The expected size of the PCR product was 1358 bp. Two of the colonies tested contained bands of the correct size, while the rest were background. These two were purified and subsequently used.

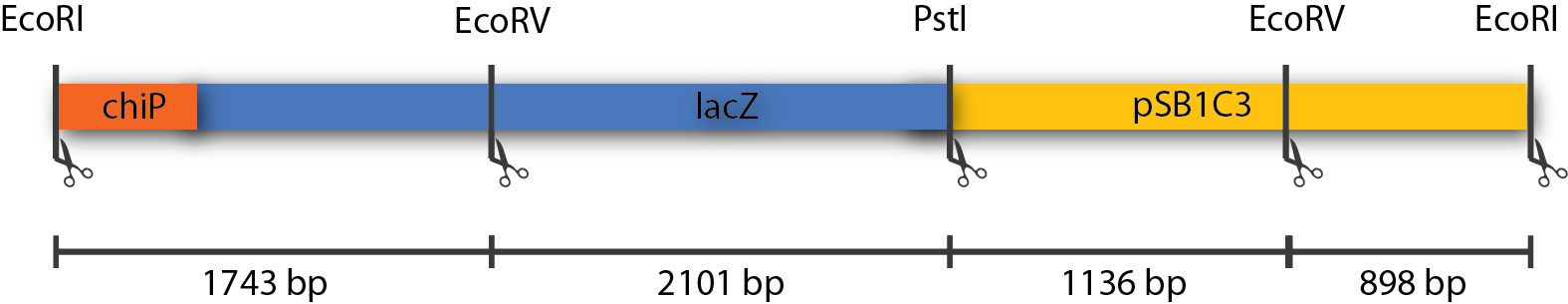

A number of PchiP-lacZ fusions were verified using restriction analysis. The expected band sizes are shown below, as is a gel-picture of the restriction:

| Restriction Enzymes | Expected sizes |

|---|---|

| EcoRI + EcoRV + PstI | 1743 + 2101 + 1136 + 898 |

Results and Conclusions

Although we believe we obtained the correct plasmids, and they were subcloned into plasmids that let us test them, we were unable to do so due to time pressure. Only a few combinations with the PchiP plasmids were performed. These are summarized in the table below:

| Strain | [http://ecoliwiki.net/colipedia/index.php/NM522 NM522] | IG302 |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | chiX + | chiX - |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K564012 PchiP(original):lacZ, BBa_K564012] | 467 | 4781 |

| [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K564013 PchiP(mutated):lacZ, BBa_K564013] | 2353 | 2403 |

We concluded that the PchiP is regulated by chiX, and that mutating the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) removes the regulatory effect of chiX on the PchiP SD. The lower baseline expression of the mutated promoter is most likely due to the slightly weaker SD.

References

[1] Datta, Simanti, Nina Costantino, and Donald L Court. “A set of recombineering plasmids for gram-negative bacteria.” Gene 379 (September 1, 2006): 109-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16750601.

[2] Figueroa-Bossi, Nara, Martina Valentini, Laurette Malleret, and Lionello Bossi. “Caught at its own game: regulatory small RNA inactivated by an inducible transcript mimicking its target.” Genes & Development 23, no. 17 (2009): 2004 -2015.

[3] Hayashi, Koji, Naoki Morooka, Yoshihiro Yamamoto, Katsutoshi Fujita, Katsumi Isono, Sunju Choi, Eiichi Ohtsubo, et al. “Highly accurate genome sequences of Escherichia coli K-12 strains MG1655 and W3110.” Molecular Systems Biology 2 (2006): 2006.0007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16738553.

[4] Lambert, Jolanda M, Roger S Bongers, and Michiel Kleerebezem. “Cre-lox-based system for multiple gene deletions and selectable-marker removal in Lactobacillus plantarum.” Applied and environmental microbiology 73, no. 4 (February 2007): 1126-35. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1828656&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

[5] Overgaard, Martin, Jesper Johansen, Jakob Møller‐Jensen, and Poul Valentin‐Hansen. “Switching off small RNA regulation with trap‐mRNA.” Molecular Microbiology 73, no. 5 (September 2009): 790-800.

[6] Rasmussen, Anders Aamann, Jesper Johansen, Jesper S Nielsen, Martin Overgaard, Birgitte Kallipolitis, and Poul Valentin‐Hansen. “A conserved small RNA promotes silencing of the outer membrane protein YbfM.” Molecular Microbiology 72, no. 3 (May 2009): 566-577.

"

"