Team:Cornell/Description

From 2011.igem.org

Project Description |

Future Directions |

Business Development |

Outreach/HP |

Safety

Contents |

The BioFactory

Cornell’s BioFactory aims to develop a simple and efficient method for the construction of enzyme-immobilized surfaces capable of multi-step chemical reactions.

As more chemical production techniques begin to utilize enzymatic reactions, genetic engineers must consider ways to resolve competing side reactions and the toxic accumulation of intermediates, reduce purification costs, and correctly express non-native enzymes or proteins in bacteria. In some cases, such challenges could be more easily resolved by simply extracting the molecular metabolic mechanisms and produce the target compound in a cell-free environment. We believe a cell-free system for biosynthesis can resolve these issues and still use the power of bacteria to help build devices capable of producing complex organic compounds.

Over the summer, Cornell's iGEM team engineered strains of E. coli to produce modified enzymes from the biosynthetic pathway of Violacein which were immobilized on the surface of microfluidic devices and capable of converting an initial feed of substrate into prodeoxyviolacein, a direct intermediate of the violacein pathway. The microfluidic chips were designed, built and tested in the lab using Cornell’s modern clean room and nanofabrication facilities. We additionally designed and began construction of a light-induced apoptosis system capable of lysing bacterial cultures, producing the necessary enzymes without the use of expensive reagents or extensive protocols.

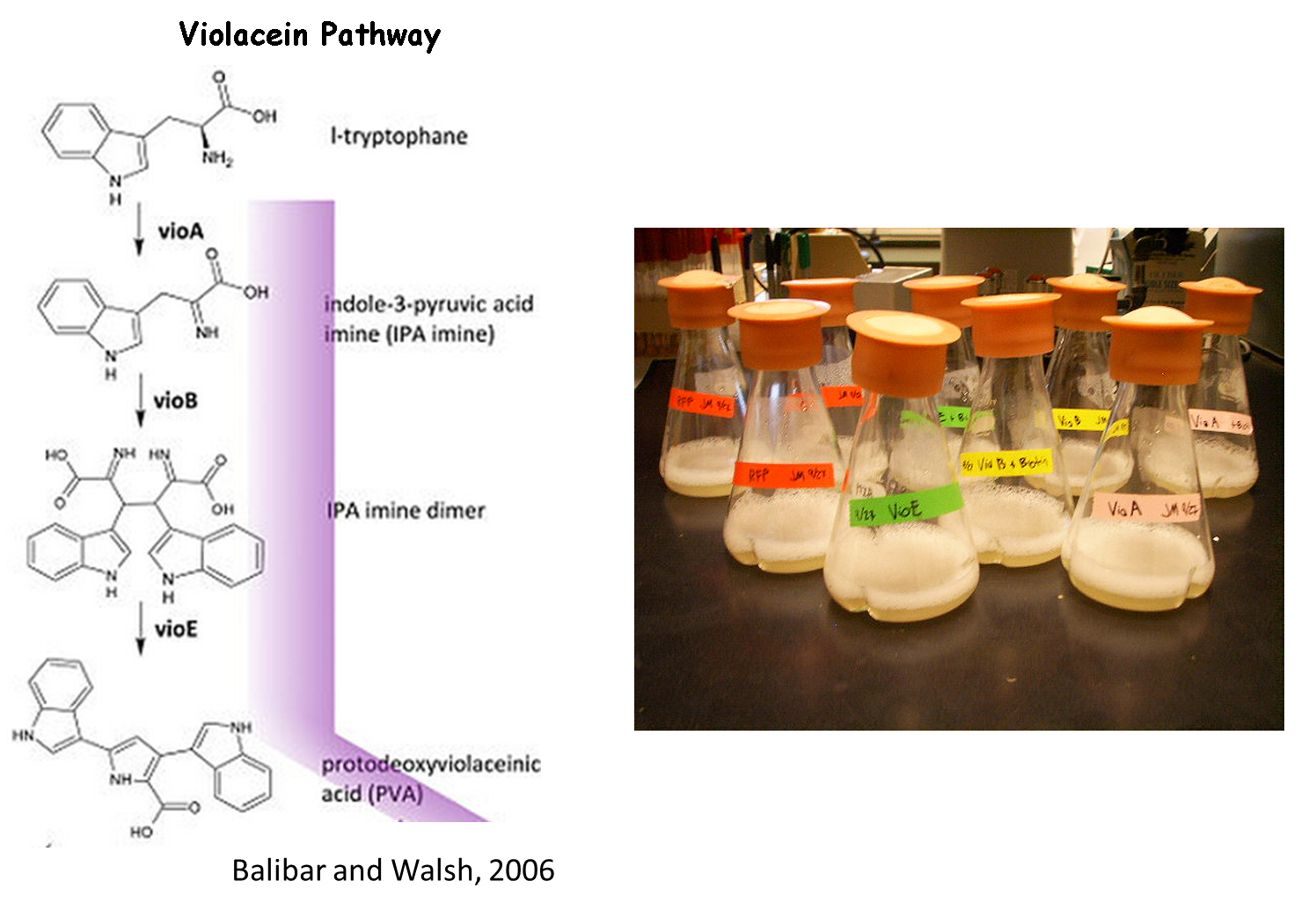

Violacein Pathway

We chose to use the violacein pathway fully characterized by Balibar et. al.3 as our model enzyme-mediated-reaction. The violacein pathway involves five enzymes (VioA, VioB, VioC, VioD, and VioE) in the conversion of L-tryptophan into violacein, a purple chromophore. This pathway was an especially attractive candidate for our project not only because it has been thoroughly characterized in E. coli, but also because relatively few enzymes are needed to convert a cheap, common substrate into a visualizable product. Furthermore, only three of the five enzymes (VioA, VioB, and VioE) are required to produce a colored product. L-tryptophan is converted into prodeoxyviolacein, a green pigment (Figure 3A in Balibar et al.3). Thus, we chose to biotinylate only VioA, VioB, and VioE to provide proof-of-concept that enzymes bound to our microfluidic devices may be used to facilitate enzyme-mediated reactions.

How To Make Our Enzymes Stick to the BioFactory:

- Have the Bacteria Do the Work

- We made use of the biotin-streptavidin binding interaction in fixing our biotinylated enzymes to the PDMS channel surfaces. E. coli has a natural mechanism encoded by the birA gene to produce biotin and biotinylate proteins. Thus, by appending the AviTag peptide to enzymes of interest and adding biotin to the bacterial culture for enhanced biotinylation of the AviTag, we functionalized our enzymes for biotin-NeutrAvidin binding to the microfluidic device. We chose the biotin-avidin interaction over the competing nickel-histidine binding method commonly used for protein purification, as the avidin-biotin binding interaction lasts longer.

- Chemical Treatment to Surface of BioFactory Devices

- Using standard chemical procedures from Gleghorn et al.1 provided by Dr. Kirby (Cornell University, Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering), NeutrAvidin was bonded to the surface of PDMS channels. NeutrAvidin is a deglycosylated version of avidin and is interchangeable with streptavidin. It has a similar tetramer structure, which binds with biotin in four regions. NeutrAvidin can bind greater than 12 µg of biotin per mg protein and has a dissociation constant Kd = 10-15 M.

- When biotinylated enzymes come into contact with the NeutrAvidin in the devices, they bind in a ligand interaction capable of withstanding the continuous flow rates of solutions against the surfaces.

The BioFactory Microfluidic System

Overview:

In order to develop a scalable synthetic pathway the team required a means to apply enzymes

to proteins extracted from lysis.

This means would have to:

- Provide large enzyme exposure area within a small volume.

- Allow for scalability for industrial application.

- Be able to accommodate a system of separate enzymes as components of a chosen biosynthetic pathway.

- Be relatively simple and inexpensive

After a series of brainstorming and development sessions during the spring of 2011, the team

decided to move forward with the creation of a microfluidic device.

Final Chip Design (7/3/2011 - 7/6/2011)

Summary:

Optimized chip size to fit 4 chips on a 4'' diameter wafer.

After discussion, changed channel dimensions back to narrow safe limits of printing machine: 200 microns wide, 200 micron spacing.

Channel margins changed to limit of safe margin for wafer size.(1cm from edge)

Inlet/outlet positioning was changed to prevent channel damage when punching inlet/outlet holes.

Final Design was approved for printing.

Solidworks Sketch converted to DXF in Solidworks. Edited in Modo. Converted to GDS using LinkCAD and printed to mask.

Basis for Revision:

- Channels dimensions needed to balance space-savings and safe-print.

- Team wanted to print as many chips in as little space as possible.

- Team aimed to minimize damage when punching inlet/outlet holes.

Features:

Material:

We chose to create our microfluidic chip out of Polydimethylsiloxane

(PDMS) because of its extensive use in biologically related

microfluidic research. PDMS is an optically clear, nontoxic,

nonflammable and inert material that is ideal for working with

biological material. It is also a cost efficient material that can

easily be fabricated into a microfluidic device.

Inlet/Outlet

- Changed inlet/outlet position to reduce wasted space and reduce loss of chips

Channel

Dimensions

- Channel width changed to 200 microns.

- Channel spacing changed to 200 microns.

- Channel depth changed to 100 microns.

Overall Dimensions

- Reduced chip print dimensions to 22.05mm by 25.00mm. Fits 4 safely on a 4'' diameter wafer. (101.6 mm diameter)

Mask

- Developed. Specifications drawing in Images below.

DXF to GDS File:

"

"