Team:Arizona State/Project/B halodurans

From 2011.igem.org

|

|

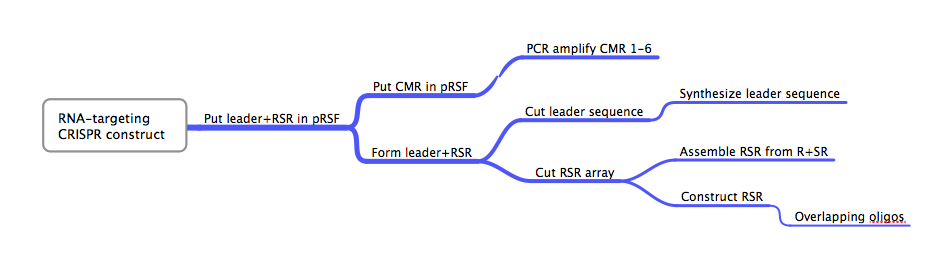

ConceptionBesides the DNA-targeting Crispr-Cas system in E. coli, our other original project was the construction of an RNA-targeting Crispr-Cas system from Bacillus halodurans. Early attempts to explain the function of the Crispr-Cas system proposed that the Crispr array was utilized to target RNA, not DNA, in a manner analogous to eukaryotic RNAi[80]. While later studies showed that DNA, not RNA, was the target of certain Crispr-Cas systems, at least one study found a Crispr-Cas system that seemed to target RNA[28][35]. This RNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas system used so-called repeat associated mysterious proteins (RAMPs) in the form of CMRs 1-6. We realized the potential importance of the successful creation and characterization of such an RNA targeting Crispr-Cas system and thought it would complement our E. coli-based DNA targeting system well. We chose B. halodurans because of its availability and because its CMR1-6 proteins are localized together on its genome, similar to the successful RNA-targeting CRISPR-Cas system[15]. DesignFlowchartThis is the experimental flowchart for the construction of our B. halodurans CRISPR platform. Beginning from the right-hand side of the diagram, this image outlines each step of the construction of our synthetically directed, RNA-targeting B. halodurans CRISPR-Cas construct. In short: Step 1) Construct RSR arrays with one of two methods:

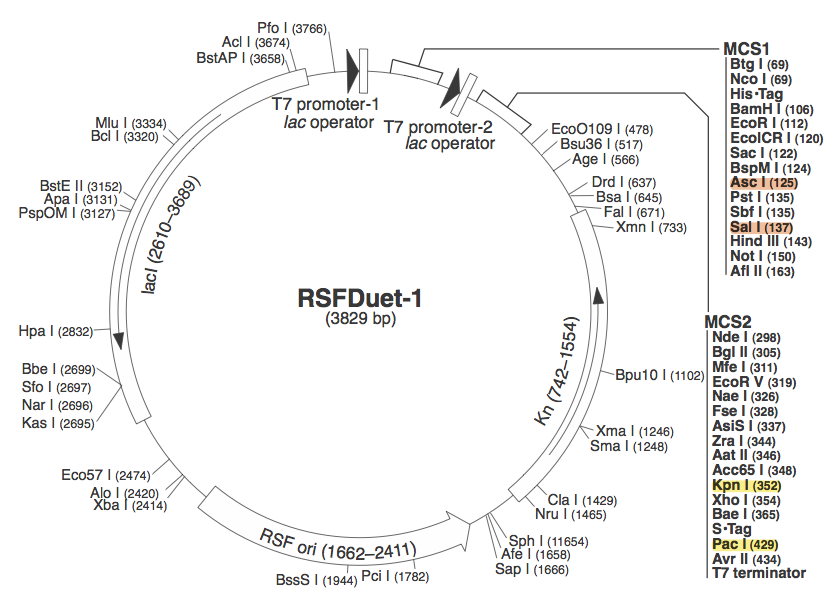

pRSF DuetWe chose to use pRSF Duet from Novagen as the vector for our construct because it has two multiple cloning sites (MCS1 and MCS2). In the image above, the restriction sites for each component of our construct are highlighted.

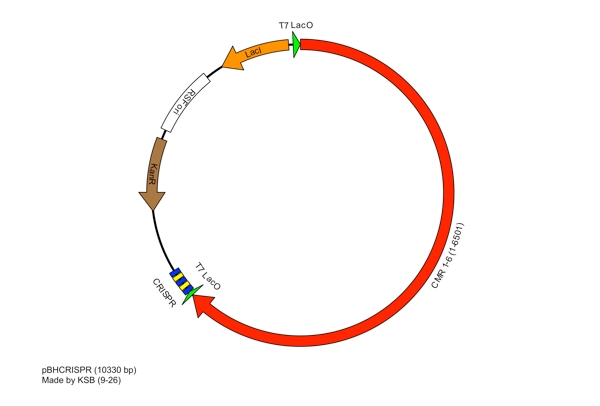

These restriction sites were specifically chosen because they do not fall within the Cas, Leader, or RSR sequences. This was confirmed using [http://tools.neb.com/NEBcutter2/ NEB Cutter]. Our PlasmidCompleting each of these steps yields this plasmid: The plasmid containing CRISPR derived from Bacillus halodurans includes the CMR region. In addition, it includes a leader sequence corresponding to B. halodurans CRISPR constructs, which is adjacent to our GFP-targeting Repeat/Spacer array. ConstructionRepeat-Spacer ArrayOriginally, we envisioned the Repeat-Spacer-Repeat (RSR) array as an easily manipulatable, modular, BioBrick-compatible component with restriction sites flanking the spacer. This would mean that once a functional CRISPR construct is constructed, all it would take is a simple restriction and ligation to insert a spacer of one's choice that corresponds to a gene of one's choice. Thus, we constructed two potential BioBricks: "RA": BB Prefix, Restriction Site #1 inside anti-GFP Spacer, Restriction Site #2, B. halodurans Repeat Sequence, Suffix

The idea here was to connect multiple RA inserts and cap the construct with a RB insert, effectively creating an array of any given length. After much work and effort trying to work with these repeated elements, we determined that we had overestimated the ease at which we could assemble arrays and so the modularity of the assembly process went from our advantage to our detriment: upon further examination of CRISPR literature, it was hypothesized that the scars left by restrictions and ligations would impede proper hairpinning and Cascade interaction of transcribed cRNA. So, we then took a different and more budget-friendly assembly approach: overlapping oligos. DNA constructs can be made by pooling numerous synthesized oligonucleotides that, together, overlap in certain parts and cover the length of the desired piece of DNA. The oligos are then subject to an assembly PCR protocol which amplifies the desired construct. In our case, it was cheaper and faster to order oligos (5 of them, ranging in size from 31 to 71 base pairs) than to order another synthesis product. For our project, we used the online program "Do-It-Yourself Gene Assembly" developed by Davidson College for their 2006 iGEM team [ http://gcat.davidson.edu/IGEM06/oligo.html].

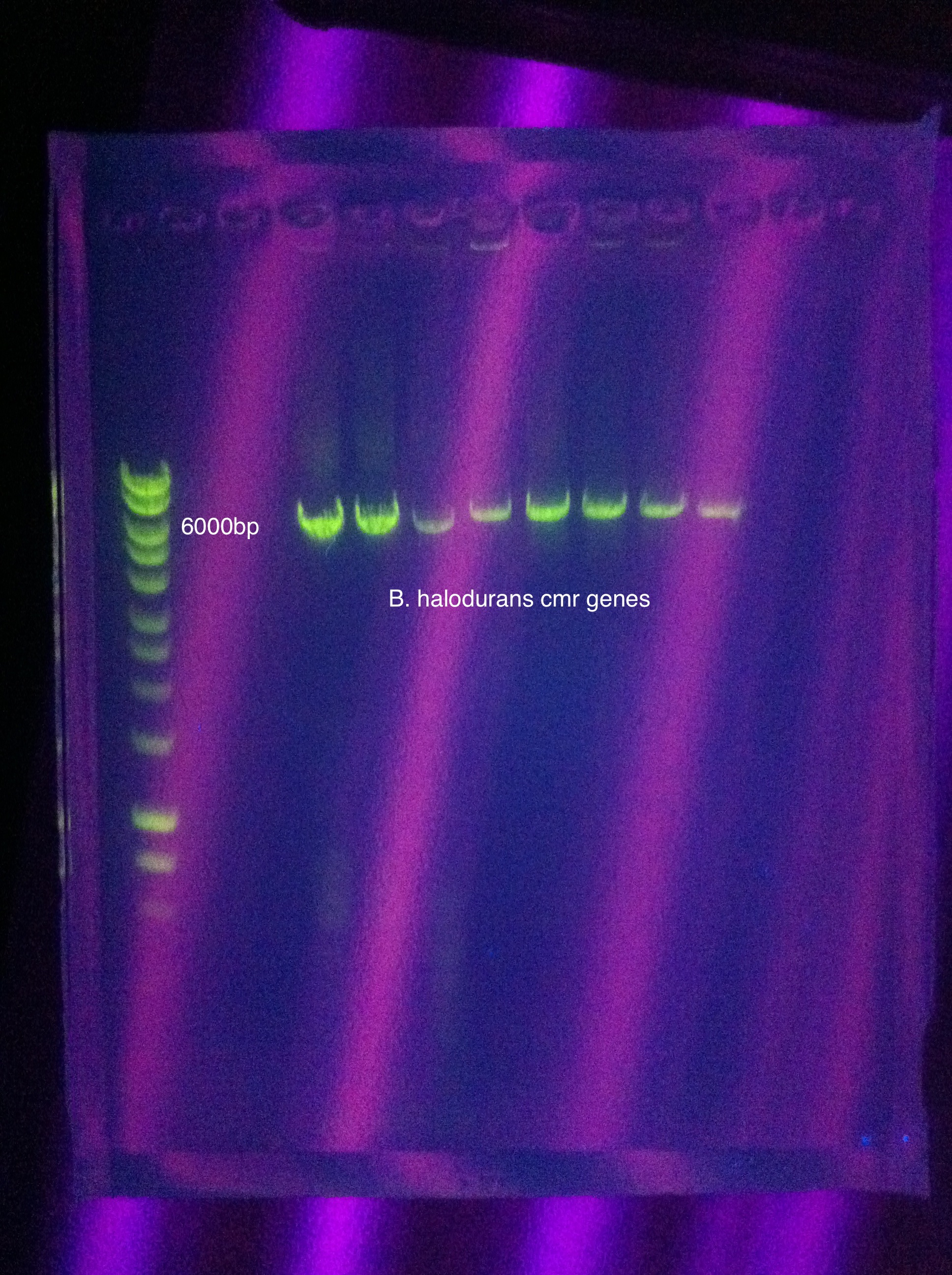

CMR genesThe ladder in the first lane is hyperladder I from Bioline, which has the following bands: 10kB, 8kB, 6kB, 5kB, 4kB, 3kB, 2.5kB, 2kB, 1.5kB, 1kB, 800bp, 600bp, 400bp, 200bp. The band for the CMR1-6 samples shows between the 8kB and 6kB band, which is where it is expected as a successful amplification of the 6500bp of the CMR1-6. FuturePreliminary data suggests that ligation of CMR1-6 into the pRSF plasmid was successful (not shown), athough further characterization is neccessary. To finish the construct, the overlapping oligos need to be assembled. This involves using T7 polynucleotide kinase to add a phosphate group to the 5' ends of the oligos, which were ordered without this modification. Then, an assembly PCR or polymerase cycling assembly protocol needs to be followed to fully make the RSR construct. This RSR construct includes restriction sites (which are not in CMR1-6) that will then allow it to be combined with the aldready-synthesized leader sequence, and finally inserted into the CMR-pRSF construct, finishing the plasmid. The finished plasmid needs to be transformed with another plamsid expressing GFP for testing in a way similar to the already-performed E. coli testing. Overcoming Tandem Repeat IssuesSimilar to the E. coli project, the assembly of tandem repeats in bacteria is wrought with difficulties. This was evident in our assembly attempts, where using conventional restriction, ligation, and transformation processes in order to construct the tandem repeats did not result in a successful Poly-X Repeat-Spacer array. One way we attempted to overcome this issue was with what we have dubbed the XS Method. Theoretically, using a series of restrictions and ligations, one can assemble multiple repeats at varying lengths and use gel electrophoresis to identify varying poly-X constructs. While we were able to successfully construct a "1x" anti-GFP array, we were unable to create the 2x, 4x, and 8x arrays that we had initially planned. In order to increase the effectiveness of our CRISPR construct, the Poly-X Method or another strategy for combating tandem repeat issues must be utilized. |

"

"