Team:Arizona State/Project/E coli

From 2011.igem.org

|

|

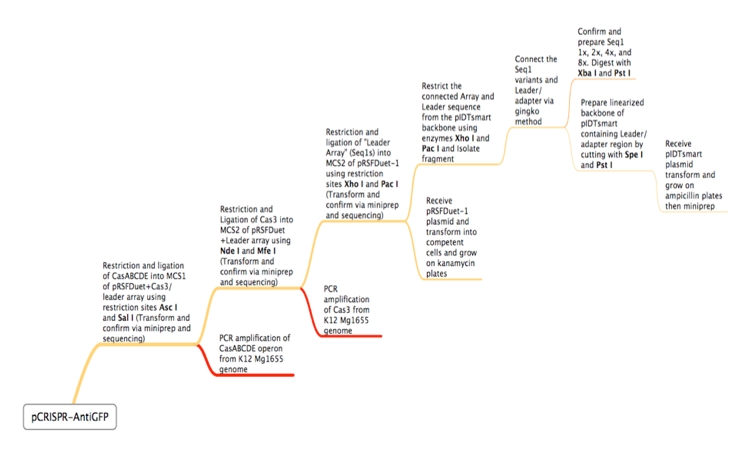

ConceptionOur first foray into manipulating CRISPR was in E. coli. We chose to use the CRISPR-Cas system of K12-MG1655 because the strain is well-characterized and it is a common lab organism, making it easy to obtain. Its ubiquity would allow for a manipulatable CRISPR platform useful in many lab applications. Another reason for seeking to synthetically direct CRISPR in E. Coli is the existence of strains that do not have Cas genes. For instance, BL21 DE3 does not have a natural CRISPR-Cas system, making it an ideal organism for the transfer of our CRISPR construct. In short, we would obtain Cas genes from MG1655, insert them into a plasmid with a Repeat-Spacer array that corresponds to GFP, and then transfer that plasmid into the BL21 DE3 host along with a constitutive GFP plasmid. If successful, the expression of GFP would be silenced or significantly decreased. Because there are E. coli strains with Cas genes and strains without Cas genes, one can easily remove Cas genes that will integrate new spacers. In this case, Cas 1 and Cas 2 were excluded, as they have been shown in literature to facilitate new spacer integration (cite). In order to properly test our CRISPR construct and ensure that silencing of GFP is a result of the addition of our pCRISPR, it is important to prevent other spacers from being added to the Repeat-Spacer array. DesignFlowchartThis is the experimental flowchart for the construction of our E. coli CRISPR platform. Beginning from the right-hand side of the diagram, this image outlines each step of the construction of our synthetically directed, GFP-targeting E. coli CRISPR-Cas construct. In short: Step 1) Construct RSR arrays with increasing numbers of anti-GFP spacers (1x, 2x, 4x, 8x)

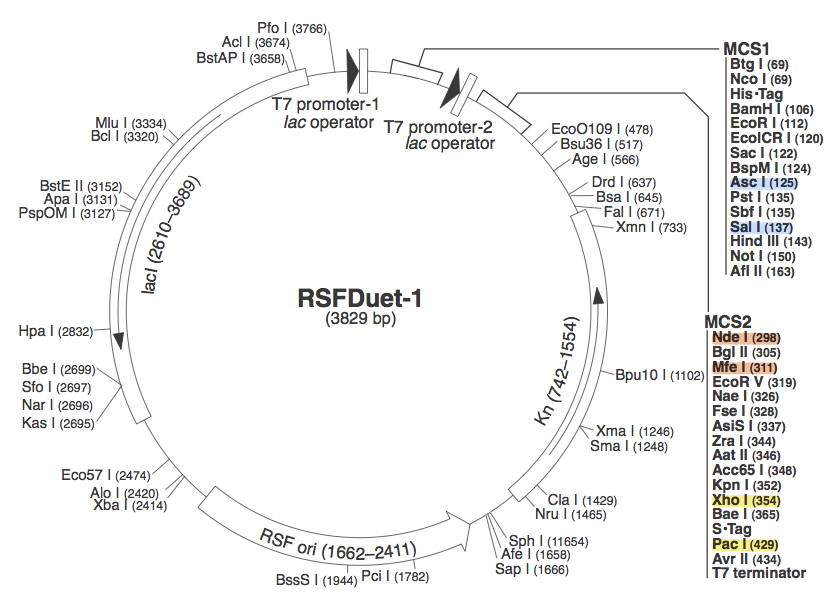

pRSF DuetWe chose to use pRSF Duet from Novagen as the vector for our construct because it has two multiple cloning sites (MCS1 and MCS2). It was used in a CRISPR study (cite, is this Brouns?). In the image above, the restriction sites for each component of our construct are highlighted. Blue - CasABCDE

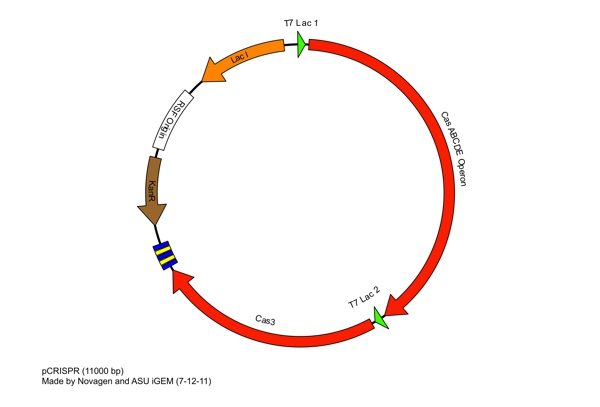

These restriction sites were specifically chosen because they do not fall within the Cas, Leader, or RSR sequences. This was confirmed using [http://tools.neb.com/NEBcutter2/ NEB Cutter]. Our PlasmidCompleting each of these steps yields this plasmid: The plasmid design for the Anti-GFP CRISPR construct in E. coli includes Cas genes A, B, C, D, E, and 3. In addition, it includes a leader sequence corresponding to most K12 CRISPR constructs, which is adjacent to our GFP-targeting Repeat/Spacer array and promotes its expression. ConstructionRepeat-Spacer ArrayOriginally, we envisioned the Repeat-Spacer-Repeat (RSR) array as an easily manipulatable, modular, BioBrick-compatible component with restriction sites flanking the spacer. This would mean that once a functional CRISPR construct is constructed, all it would take is a simple restriction and ligation to insert a spacer of one's choice that corresponds to a gene of one's choice. Thus, we constructed two potential BioBricks: "DA": BB Prefix, Restriction Site #1 inside Spacer that is anti-complementary to GFP, Restriction Site #2, MG1655 Repeat Sequence, Suffix

The idea here was to connect multiple DA inserts and cap the construct with a DB insert, effectively creating an array of any given length. However, upon further examination of CRISPR literature, it was hypothesized that the scars left by restrictions and ligations would impede proper hairpinning and Cascade interaction of transcribed cRNA. In lieu of this, a third potential BioBrick was designed: "Seq1": BB Prefix, Repeat, anti-GFP Spacer, Repeat, BB Suffix Our team had all three constructs synthesized by [http://www.biobasic.com/ BioBasic], and attempted to restrict, ligate and transform (RLT) poly-x constructs (1x, 2x, 4x, 8x). We used pUC57 primers to PCR amplify the inserts. File:Gel of pcr amp of DA, RA, Seq1 After many rounds of troubleshooting different assembly methods, which are detailed in our Notebook, we decided to proceed by testing 1x RSR. Leader+RSRWe synthesized the MG1655 leader sequence through [http://www.idtdna.com/Home/Home.aspx Integrated DNA Technologies]. We then inserted Seq1, our 1x RSR, into the pIDT vector alongside the leader sequence. File:Gel result, compare leader to leader+RSR Cas genesContingencyDue to the difficulties surrounding the isolation of the MG1655 Cas genes, we decided to proceed with a contingency plan for testing our synthetic manipulation of the E. Coli CRISPR-Cas system. This entailed introducing the anti-GFP array, comprised of the E. Coli leader sequence adjacent to a single Repeat-Spacer-Repeat (RSR), into a strain that already has a CRISPR-Cas system with the intention of using the endogenous Cas proteins with our synthetic array. To do this, we ran a series of transformations to introduce 2 plasmids to K12 MG1655: a constitutive GFP plasmid and our Leader+RSR array. This was done in a two-step process. First, one plasmid was transformed into the strain, grown up in a liquid culture, and made competent. Then, the second plasmid was transformed into these competent cells, and results were observed. A few sets of controls were utilized in this setup to isolate the effect of the introduced Leader+RSR plasmid on the expression of GFP. The order of introduced plasmids was alternated to see if it affected the function of the CRISPR array. In addition, a pIDT plasmid containing only the Leader sequence and not the RSR was ran in parallel with Leader+RSR to compare expression of GFP, given that the RSR is needed for the CRISPR-Cas system to function. Lastly, each of these combinations was also tested in a strain of bacteria that does not contain endogenous Cas genes, BL21 DE3. We used an 8 plate transformation format, using six types of prepared competent cells: MG1655 with GFP in pRSF

See images of these cells [(link to notebook) here]. Contingency TestingOnce we had the necessary plasmids prepared, we proceeded to execute the contingency testing process. In order to conduct the tests with a relatively rigorous level of experimental control, we devised a method of standardizing the creation of competent cells containing the aforementioned plasmids of interest. After growing up the transformants in overnight liquid cultures, we measured the absorbance of the liquid cultures prior to their preparation as chemically competent cells. Then, upon conducting a 1/100th dilution of these overnight liquid cultures into their corresponding media, we grew the cells up for another 2 hours as per the TSS Protocol, and measured their subsequent absorbance values. These absorbance values, each collected with 100 uL (0.1 cm3) of liquid culture sample, were then used to calculate the respective OD600 values using the known dimensions for the 96-well tray used in the spectrophotometry.

These mean OD600 values for each transformant variety immediately following the 2 hour grow period could then be correlated to the resulting transformation results with regard to apparent colony quantity. Since each transformation we conduct utilizes 50 uL of competent cells, the optical densities implied relative quantities of available competent bacterial cells during each transformation. Once each transformation was performed for one round of this standardized contingency testing process, the viability of the cells upon introduction of the final plasmid in the contingency testing process could be evaluated using the Weighted Colony Count (WCC). The WCC, calculated by dividing the number of visible colonies by the corresponding OD600 value, provides a quantity that correlates the observed number of colonies to the initial quantity of available competent bacterial cells as determined by the mean OD600 proceeding dilution for competency preparation.

**Weighted Colony Count = (# of Colonies)/(mean OD600 of competency prep) Immediate visual observation of the colonies made it clear that the MG1655 strain containing the Crispr-cas system had not behaved as we had expected it to upon introduction of the Leader+RSR plasmid, and this conclusion was reinforced by the calculation of the WCC values. We had expected the Crispr-Cas system present in the MG1655 to linearize the introduced GFP plasmid with the selected antibiotic resistance, and as such, to subsequently reduce viability of the cells. Contrary to our expectations, the competent cells containing the MG1655 Leader+RSR plasmid which were subject to a GFP plasmid with the selected antibiotic resistance during transformation exhibited a WCC that seemed to imply a significantly increased viability of the cells. The BL21 strain was more consistent in its overall low transformation efficiency; however it was more of a comparative control than an indicator of Crispr-Cas activity, and the results of the BL21 transformations did not impact our findings regarding the Crispr-Cas system. FutureWe learned some very useful information from our explorations into the CRISPR-Cas system of E. coli, both from our successes and our failures. These lessons directly contributed to the evolution of our B. halodurans and L. innocua projects throughout the summer. In the future, we may continue our efforts to construct and synthetically direct the CRISPR-Cas system of E. coli, taking into consideration what we have learned from unsuccessful attempts. However, the simplicity of the L. innocua platform lends itself well to our original intents with the E. coli system, making it ideal for the continuation of our research. Either way, we will utilize what we have learned from these attempts. Overcoming Tandem Repeat IssuesAs evidenced in previous literature (cite), the assembly of tandem repeats in bacteria is wrought with difficulties. This was evident in our assembly attempts, where using conventional restriction, ligation, and transformation processes in order to construct the tandem repeats did not result in a successful Poly-X Repeat-Spacer array. One way we attempted to overcome this issue was with what we have dubbed the XS Method. Theoretically, using a series of restrictions and ligations, one can assemble multiple repeats at varying lengths and use gel electrophoresis to identify varying poly-X constructs. While we were able to [(link) successfully construct] a "1x" anti-GFP array, we were unable to create the 2x, 4x, and 8x arrays that we had initially planned. In order to increase the effectiveness of our CRISPR construct, which increases with an increasing abundance of spacers (cite), the Poly-X Method or another strategy for combating tandem repeat issues must be utilized. Complexity of E. coli Cas genesThe E. coli CRISPR-Cas system is more complex than that of both B. halodurans and L. innocua. E. coli: 8 Cas genes, (length)

In our attempts at PCR amplification of CasABCDE (~4300bp) and Cas3 (~2700bp), we were not able to successfully isolate these genes. We tried using two different laboratory strains of K12 MG1655 and 3 rounds of primers, one of which was adapted from a published study (link to Brouns). While we were able to identify what we assumed to be the correct gel bands in a few of our dozens of amplification attempts, results were often faint and inconsistent. It is important to note that, in contrast, the Cas genes for B. halodurans were [(link) successfully amplified] on the very first try. The difficulty of isolating these genes may be somehow related to the particular lab strains that we used, which were obtained from two different ASU laboratories. It is possible that it is related to a protective mechanism or undiscovered aspect of the CRISPR system, as CRISPR-Cas research is relatively new and understanding is incomplete. Regardless, the E. coli Cas array is long and complex, lending argument to the advantages of our B. halodurans and L. innocua projects. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"

"