Team:Harvard/Bioinformatics

From 2011.igem.org

Contents |

Terminology

- Backbone: contains most of the amino acids of a zinc finger protein: zif268 is the most famous backbone.

- Fingers: contain a backbone and a helix, bind to a 3-base DNA triplet

- Helix: the alpha helix in a finger. It is responsible for binding to a DNA triplet. Helices are made up of 7 amino acids, and fit into a specified position in a backbone.

- Zinc finger proteins (ZFPs): arrays of three fingers that bind to 9 bases (3 triplets) of DNA.

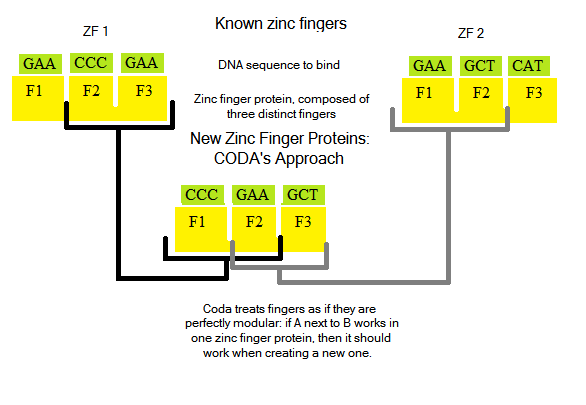

[Diagram]

Past Zinc Finger Designers

Designing new zinc finger proteins (ZFPs, which are arrays of three fingers) is not an easy task: how they bind and interact with DNA bases is not fully understood, and is an active area of research [Persikov]. Notable past attempts to create novel ZFPs [CODA, OPEN] tried a two distinct methods: CODA took a modular approachOPEN took two known fingers from an array, and randomized protein sequences to try to generate a third finger to bind a new triplet:

Both techniques were successful in finding ZFPs to bind to novel DNA sequences [how successful?]

Our Approach

Improving on the concept of OPEN, we decided to design ZFPs where the first two DNA triplets can be bound, but the third cannot. For example, if the sequence GTG GGA CCA can be bound but GTG GGA TGG cannot, we would use the first two fingers and generate the third. OPEN simply randomized amino acid sequences to try to create a third finger: we wrote software that uses data from known fingers to "intelligently" generate new fingers.

Data and Analysis

OPEN provided us with a spreadsheet of ZFPs produced by their research. Anton Persikov, during his own ZFP research, has compiled a database of ZFPs from studies from 1980-2005 which he shared with us.

From these two datasets, we distilled over [3000] unique ZFPs which contained approximately [1400] unique fingers.

We analyzed this dataset for frequency (how often a given amino acid appears in a given position in the helix) and pairing (if amino acid A is in position 1, how often is amino acid B next to it).

Helix Dependencies

Amino acids do not exist in a vacuum: they must somehow be affected by amino acids around them. Besides pairing data, we realized that other interactions could be taking place, and that we would miss these interactions if we only looked at pairing.

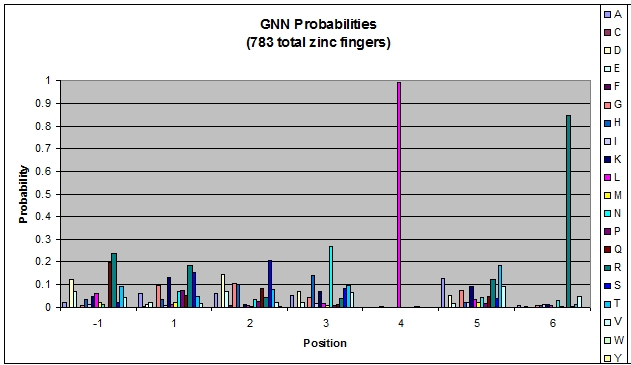

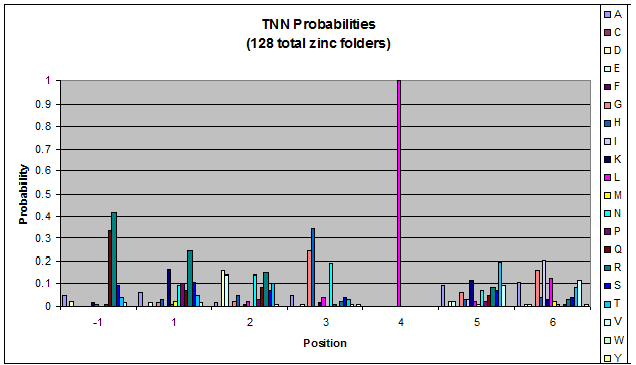

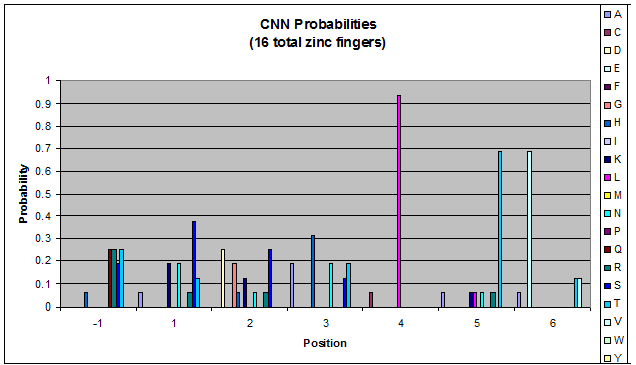

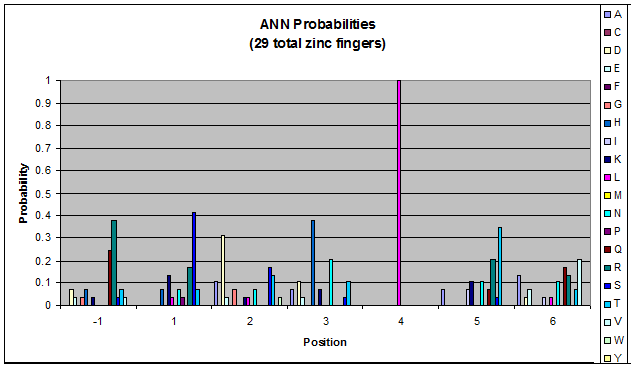

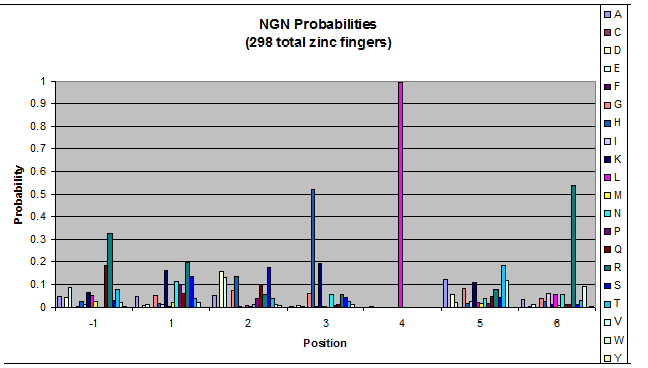

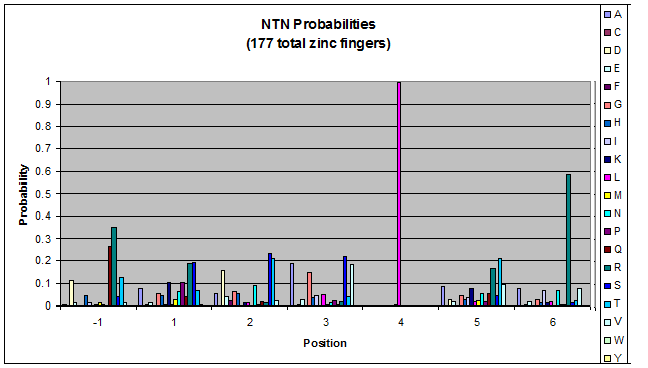

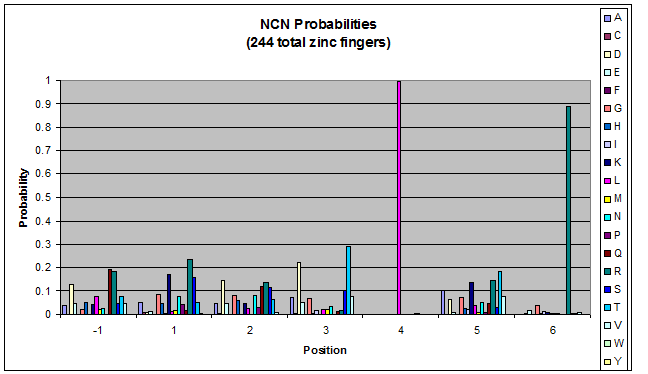

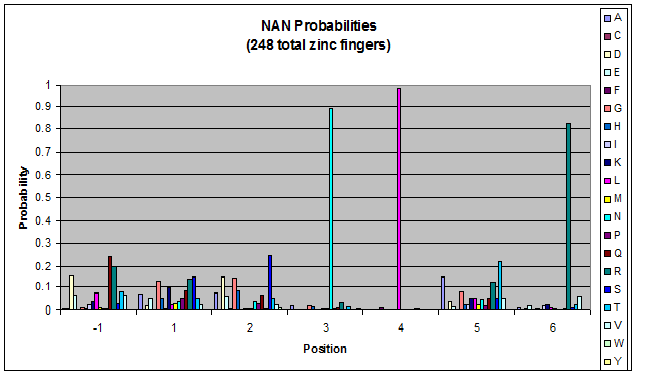

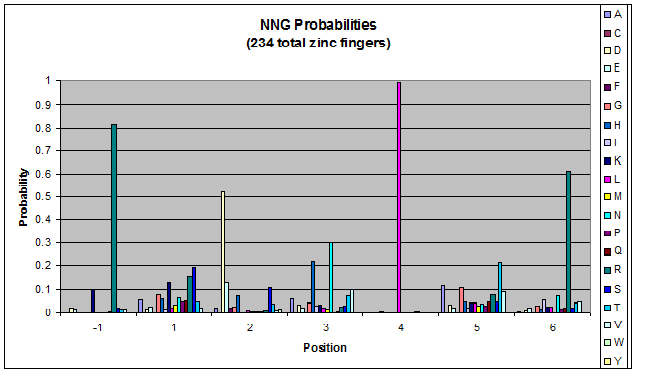

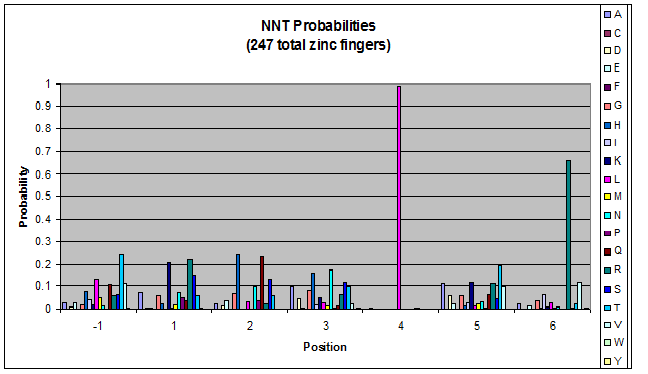

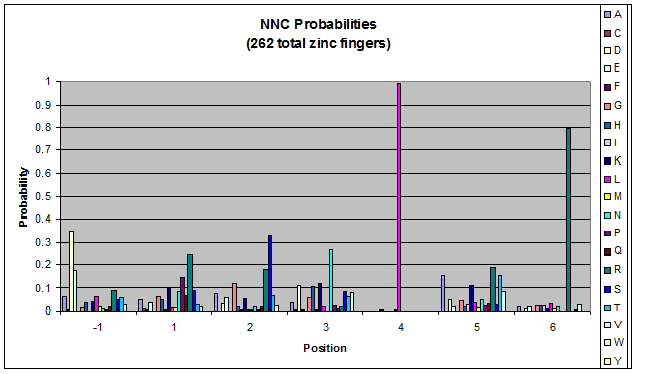

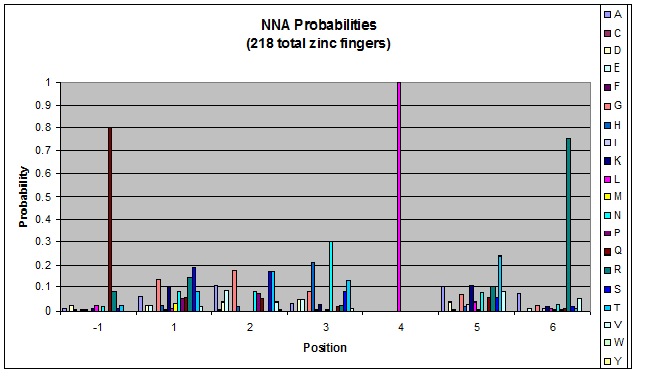

We created these graphs of the frequency of amino acids in each position, and then [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blink_comparator blink] the graphs against each other to see what changes. We looked at the probability graphs to determine which amino acid positions on the finger's helix interact with which bases. Some interactions are fairly well estabilished, while others have been more recently proposed [Persikov]

| GNN |

| TNN |

| CNN |

| ANN |

| NGN |

| NTN |

| NCN |

| NAN |

| NNG |

| NNT |

| NNC |

| NNA |

(A more rigorous way to calculate this is to calculate the entropy change as you change the amino acids in each position. But that is computationally intensive)

By doing this, we were able to see several patterns.

- xNN(Vary base 1): Amino acid 6 changes

- NxN(Vary base 2): Amino acid 3 changes

- NNx(Vary base 3): Amino acid -1 and 2(?) changes

Our program looks at dependencies between amino acids when generating sequences.

We decided on these amino acid dependencies, using both established data and patterns we saw in the OPEN data:

- -1 and 2

- 2 and 1

- 6 and 5

Because there is not much data for 'CNN' and 'ANN' sequences (with 16 and 29 known fingers that bind to each triplet, respectively), we should use pseudocounts for these sequences, so that our frequency generator is not too biased toward probabilities that may not be significant.

Programming

Probabilities and Randomization

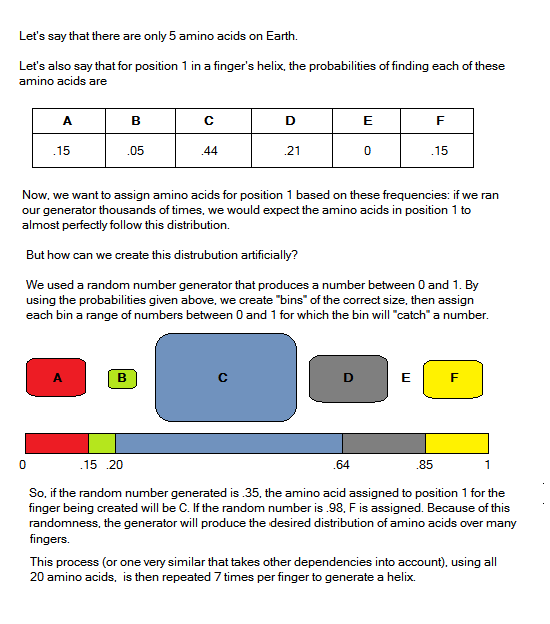

Our generation program uses these amino acid frequencies as probabilities that position X contains amino acid X, given what triplet we are trying to bind. Using the dependencies we found, we change which frequency tables are used to generate the new helix.

See the image at right for a more through explanation.

"

"