Team:UT-Tokyo/Project/System

From 2011.igem.org

Project

iGEM UT-Tokyo

System

Project Overview

As we stated in the Background page, our SMART E.coli project aims at improving the working efficiency of bioremediation. To achieve this goal, we have designed the following two sub-systems. We first developed a Cell Assembling System, in which E. coli detecting a substrate attract other cells nearby via chemoattraction, therefore elevating the bacterial density of the substrate location. We constructed and tested an inducible L-aspartate (L-Asp) producing device using an enzyme aspA. Second, we devised a Cell Arrest System to prevent a time-dependent cell diffusion so that the elevated cell density is maintained. In this system, E. coli flagellum-regulating gene, cheZ, was utilized to realize a switching of cell motility. By combining these two mechanisms, cell density at the location of substrate is expected to be greatly elevated and maintained, so that enhanced working effectiveness will be achieved.

To further enlarge the application of our SMART System, we also provided a "UV Switch", which enables us to switch on the SMART System even when a proper substrate-induced promoter does not exist. We investigated several UV-induced promoters, and successfully confirmed and characterized the UV-induced alteration of sulAp expression. Combining the UV Switch with our SMART System, it becomes possible to "switch on" the self-assembling and localization at the location of our interest, which greatly enhances the future applications of this SMART System.

Section1: Substrate-induced Cell Assembling System

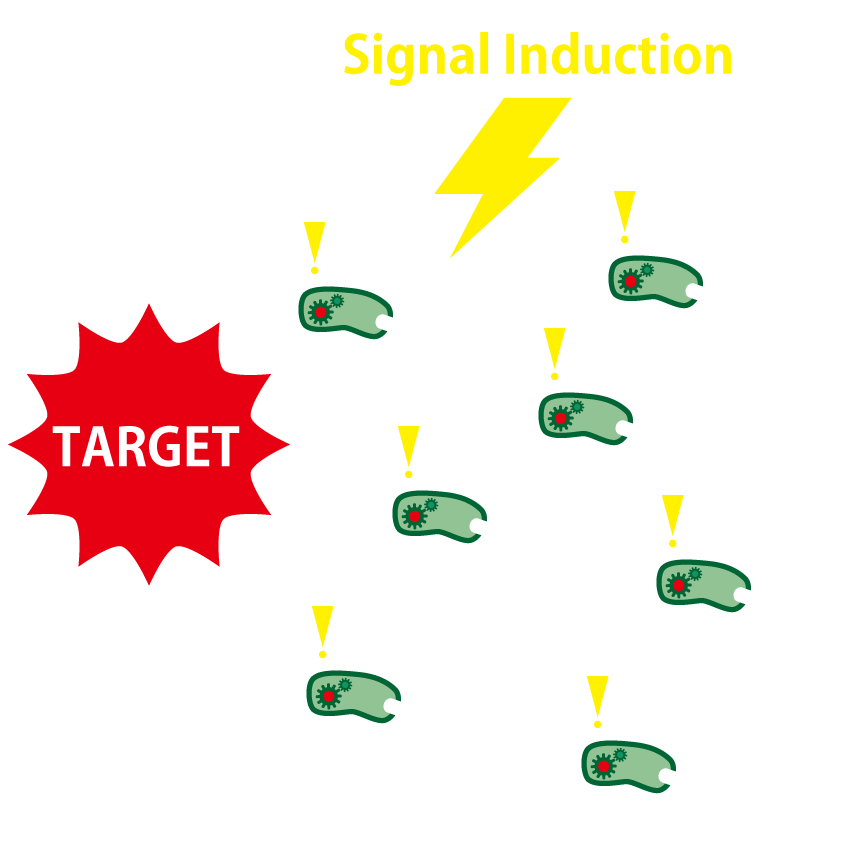

E.coli have a native property called 'chemotaxis,' and are attracted to certain substances called 'chemoattractants.' E.coli detect and move towards a higher concentration of the substances.

In our system we utilize this property to increase cell density. Specifically, we aim to realize substrate-responsive chemoattractant overproduction and a resultant cell assembly to the substrate.

The chemoattractant we have utilized is aspartate (L-Asp). Aspartate has previously been shown to act as a chemoattractant[1], which we confirmed by our own experiment, the cell diffusion assay. By making E.coli discharge aspartate, an aspartate concentration gradient around these bacteria is generated. Workers are attracted, creating a higher cell density around the aspartate-secreting E.coli.

We have devised a substrate-responsive aspartate overproduction mechanism. By utilizing this mechanism, guiders overproduce and secrete aspartate in response to a particular substrate and attract other bacteria to enhance cell density around the substrate.

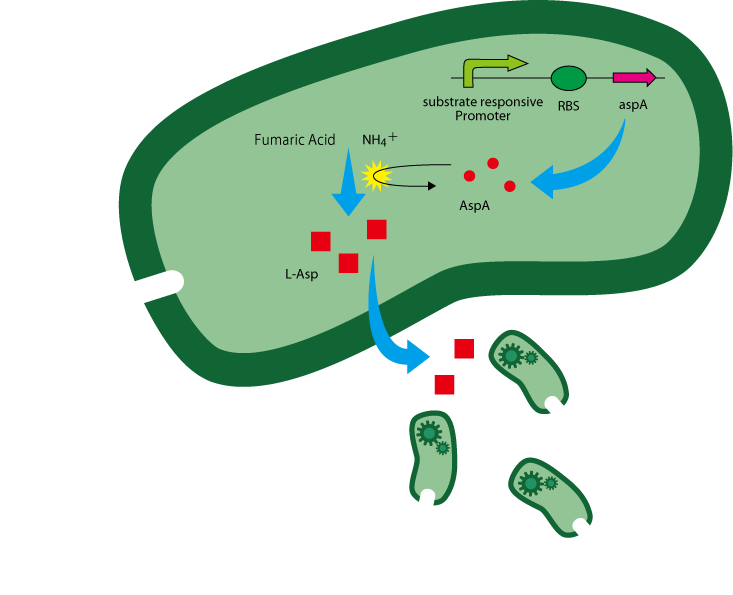

The following is the gene construct we designed.

The coding sequence of aspA is inserted downstream of a substrate-responsive promoter. The reaction of aspartate production from fumaric acid and ammonium ion is catalyzed by aspartase(AspA) encoded by the gene aspA[2]. (Figure. 1)

L-Asp is overproduced in the presence of enough AspA and the two substrates.

Note that because asp chemoattraction is native to E.coli, guiders are also attracted to the substrate. Attracted guiders also produce aspartate, giving rise to a positive feedback in which guiders are continuously added and create even higher aspartate concentrations.

Section 2: Substrate-induced Cell Arrest System

As the reaction catalyzed by AspA is reversible, when the aspartate concentration around guiders becomes too high, the reaction reaches equilibrium and so additional aspartate cannot be produced. In addition, the substrates for AspA (fumaric acid and ammonium ion) may be limited. For these reasons, aspartate secretion by guiders does not last forever. The aspartate concentration gradient produced by guiders is gradually lost by diffusion as time elapses. Consequently, in order to maintain a high worker bacteria density, we attempted to "arrest" the bacteria at the target location to prevent bacteria from escaping. To achive this, we have developed a mechanism that make bacteria less motile when they are at the target location by manipulating flagellar movement.

Bacterial chemotaxis and flagellar movement has been extensively investigated and the molecular basis for E.coli chemotaxis is understood. According to a previous study[3], a gene named cheZ, which codes for a protein involved in chemotactic signaling pathway, regulates cell motility. More specifically, cheZ, constitutively expressed in E.coli, phosphorylates a flagellar motor binding protein called CheY, making the cell motile. Therefore, cells are motile in the presence of cheZ and immotile in the absence of cheZ.

In order to make those working bacteria remain at a target site, we need to lower cell motility when they are exposed to the substrate. Put in another way, we want cheZ to be expressed in the absense of the substrate and repressed in the presence of the substrate.

To achieve this, we utilize a cheZ knockout strain to eliminate baseline expression and devised the gene construct shown below, in which cheZ expression is repressed in a substrate-dependent manner. (Figure. 3)

When the cell does not detect the substrate, cI inhibitor is not expressed and therefore cheZ is expressed and the product rescues motility of the cheZ- strain. Once the cell detects the substrate, the substrate-responsive promoter is activated and cI inhibitor is expressed. cI inhibitor then inhibits the activity of cI promotor and thereby represses cheZ expression, which leads to substrate-induced loss of motility.

By combining these two mechanisms, cell density at the location of substrate is expected to be greatly elevated and maintained, so that enhanced working effectiveness will be achieved.

Section3: UV Switch

Our SMART System has a certain problem in that an initial induction is required for the activation of the System. So, our SMART system is at this point only applicable when transcription factors responding to the targeted substrate are already known. For instance, MerR and its responsive promoter can be combined with the SMART System for mercury remediation, since the transcriptional factors (MerR and responsive promoters) have already been investigated [4].

To address this issue, we provided a well-characterized easy-inducible promoter as a genetic switch.

References

- [1] Topp S, Gallivan JP. Guiding bacteria with small molecules and RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129(21):6807-6811.

- [2] Chao Y, Lo T, Luo N. Selective production of L-aspartic acid and L-phenylalanine by coupling reactions of aspartase and aminotransferase in Escherichia coli. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2000;27(1-2):19-25.

- [3] Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9(3):153-165.

- [4] O'Halloran, T. V., Frantz, B., Shin, M. K., Ralston, D. M., & Wright, J. G. (1989). The MerR heavy metal receptor mediates positive activation in a topologically novel transcription complex. Cell, 56(1), 119-129.

"

"