Team:Washington/Alkanes/Background

From 2011.igem.org

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

8. Microbial Biosynthesis of Alkanes Andreas Schirmer, Mathew A. Rude, Xuezhi Li, Emanuela Popova and Stephen B. del Cardayre Science 30 July 2010: Vol. 329 no. 5991 pp. 559-562 http://www.sciencemag.org/content/329/5991/559 | 8. Microbial Biosynthesis of Alkanes Andreas Schirmer, Mathew A. Rude, Xuezhi Li, Emanuela Popova and Stephen B. del Cardayre Science 30 July 2010: Vol. 329 no. 5991 pp. 559-562 http://www.sciencemag.org/content/329/5991/559 | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

Revision as of 22:38, 14 September 2011

Petroleum, an Unfortunate Necessity

Modern society is completely dependent on petroleum based fuels. Automobiles are slowly transitioning towards electric power. However, for the foreseeable future, batteries will not be able to hold the energy needed for applications that require long range (e.g. jet planes, maritime shipping, and long range trucking) or high horsepower (e.g. agriculture, construction, industry). Without the use of petroleum, society as we know it would crumble.

Petroleum is not a viable long term fuel due because it a non-renewable resource. When petroleum based fuels are combusted, CO2 is released into the atmosphere. Using current technology, it is impossible to turn this carbon dioxide back into fuel, meaning that the amount of petroleum based fuel is a finite commodity. In addition, this excess carbon dioxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming.

Biofuels are a Never-ending, Renewable Resource

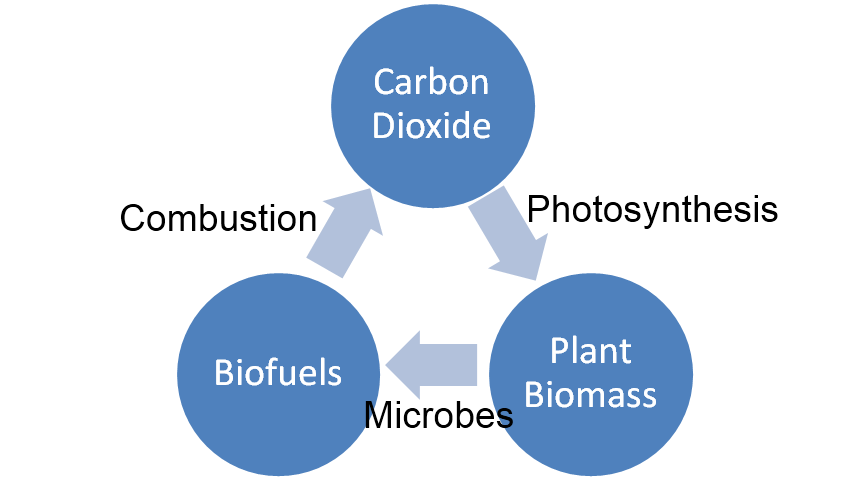

Many different attempts have been made to produce a renewable, biologically derived fuel that would alleviate both the limited supply and emissions issues presented by petroleum based fuels. These efforts include alcohols (ethanol, butanol and other, higher alcohols), and biodiesel . Like petroleum based fuels, biofuels consist of combustible molecules that emit carbon dioxide. However, unlike petroleum based fuels, biofuels are renewable. CO2 can be converted into more biofuel by feeding biofuel producing microbes (bacteria, yeast) photosynthetically derived plant biomass. Since the amount of CO2 produced by burning a biofuel cannot exceed the CO2 incorporated into plant biomass, a biofuel can be used indefinitely without any net carbon emissions.

Current Biofuels Cannot Replace Petroleum

However, current biofuels consist of drastically different compounds from those found in petroleum. Petroleum consists of mostly long-chain length alkanes consisting of long hydrocarbon chains. Current biofuels contain either alcohols or long chain esters (biodiesel). Both of these molecules contain oxygen, which dramatically changes chemical properties. Both alcohols and biodiesel are more corrosive than unreactive alkanes. Alcohols are highly corrosive, both in pipelines ( [1] ), and in engines not designed for the use of alcohols, even at concentrations as low as 20%( [2] ). The corrosive property of alcohols in pipelines means that ethanol (the main alcohol in widespread use) is transported in vehicles (mostly by train)(cite), as opposed to by cheaper and less energy intensive pipelines( [1] ). Transport of alcohols by pipeline would require retrofitting the entire fuel distribution infrastructure. The Esters in biodiesel are not directly as corrosive as alcohols, but can be biodegraded by anaerobic bacteria, producing hydrogen sulfide and other acids( [3] ). Biodiesel has a higher freezing point than diesel, causing engine fuel filer clogging at low temperatures( [4] ). Ethanol suffers from a much lower energy density than diesel(21.27-23.56 MJ/L vs 32.36-34.66 MJ/L)( [5] ), resulting in lower gas mileage.

The ideal fuel would be compatible with modern engines and infrastructure, and also be able to be produced in a renewable manner. No current biofuel has properties similar enough to that of diesel to be able to fully integrate with current engines and infrastructure. The table below shows selected chemical properties of diesel as well as ethanol and biodiesel( data from [5] and [6]).

| Property | Diesel | Ethanol | Biodiesel |

| Specific gravity @ 15.5°C | 0.85 | 0.794 | 0.88 |

| Density @ 15.5°C(g/L) | 848.25 | 792.05 | 878.09 |

| Energy Density(MJ/L) | 32.36-34.66 | 21.27-23.56 | 33.32-35.66 |

| Cetane number | 40-55 | 0-54 | 48-65 |

| Freezing point(°C) | -40 - -1 | -114 | -3 -19 |

| Viscosity( @ 20°C)(mm2/s) | 2.8-5.0 | 1.5 | 6.4-6.6 |

| Flash point(°C) | 60-80 | 12.8 | 100-170 |

Microbially Produced Diesel Production: The Best of Both Worlds

No known alternative fuel is able to match the chemical properties of diesel. Currently, the only way to renewably produce a fuel with the chemical properties and compatibility of diesel would be to make a biofuel with a composition identical to that of diesel. This would require a biological pathway that is able to produce alkanes, the main class of compounds in diesel. Alkanes are simple chains of carbon and hydrogen. The majority of the alkanes found in diesel have a carbon chain of 10 to 20 carbons long. Alkanes make up approximately 62% of jet diesel (a fairly representative diesel fuel)( [7]). This 62% includes 34% straight chain alkanes that contain only one linear chain, and 28% branched chain alkanes that contain 1 or more carbon branches. The remaining 38% consists mostly of cyclic and aromatic hydrocarbons. If long (10+) chain length alkanes could be biologically produced, it would allow for the production of a fuel that is both renewable and fully compatible with current engines and infrastructure.

The Solution: a Microbial Alkane Production Pathway

A recent study( [8]) conducted by LS9, inc. has shown the production of long chain length alkanes in E. coli using two genes found in many cyanobacteria species. The first gene codes for Acyl-ACP Reductase (AAR) which reduces long chain length acyl-ACPs into the corresponding fatty aldehydes. Acyl-ACPs are essential intermediates in fatty acid biosynthesis in every known organism, meaning that this system can work in a wide range of organisms. This long chain fatty acid acts as a substrate for Aldehyde Decarbonylase (ADC), the enzyme that removes the carbonyl group (C=O) from the fatty aldehyde, yielding an alkane one carbon shorter than the original Acyl-ACP and a molecule of formate. Since the vast majority of the fatty acyl-ACPs produced by E. coli have an even chain length, this system produces detectable amounts of only odd chain length alkanes. This study reported production of the C13, C15, and C17 alkanes, as well as the C17 alkene (unsaturated hydrocarbon), with a maximum alkane yield of 300 mg/L. This chain length range fall well within the range of those found in diesel, so this system is theoretically able to make the alkane portion of a fuel compatible with current engines and infrastructure.

Making a Modular Alkane Production System

The goal of our Diesel Production product is to turn the AAR/ADC alkane production system into an open, modular framework for future improvements on this alkane production system. Our alkane production system is specifically designed to be easily improved upon, and we have started work on improving this open system, both by increasing alkane yields and by changing the product produced. In addition, we have started to move this system into an alternative chassis, yeast.

References:

1. http://ourenergypolicy.org/docs/2/biofuels-taskforce.pdf

2. http://www.environment.gov.au/atmosphere/fuelquality/publications/2000hours-vehicle-fleet/pubs/2000-hours-vehicles.pdf

3. Anaerobic Metabolism of Biodiesel and Its Impact on Metal Corrosion Deniz F. Aktas, Jason S. Lee, Brenda J. Little, Richard I. Ray, Irene A. Davidova, Christopher N. Lyles, Joseph M. Suflita Energy & Fuels 2010 24 (5), 2924-2928(http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/ef100084j)

4. http://www.mda.state.mn.us/news/publications/renewable/biodiesel/biodieselcoldissues.pdf

5. http://www.afdc.energy.gov/afdc/pdfs/fueltable.pdf

6. The viscosities of three biodiesel fuels at temperatures up to 300°C R.E. Tate, K.C. Watts, C.A.W. Allen K.I. Wilkie Fuel 2006 85, 1010-1015 (https://netfiles.uiuc.edu/mccrady/shared/Biodiesel/The%20viscosities%20of%20three%20biodiesel%20fuels%20at%20temperatures%20up%20to%20300%208C.pdf)

7. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA317177&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf

8. Microbial Biosynthesis of Alkanes Andreas Schirmer, Mathew A. Rude, Xuezhi Li, Emanuela Popova and Stephen B. del Cardayre Science 30 July 2010: Vol. 329 no. 5991 pp. 559-562 http://www.sciencemag.org/content/329/5991/559

"

"