Team:Washington/Alkanes/Future/Modeling

From 2011.igem.org

Emily Yang (Talk | contribs) (→Background) |

Emily Yang (Talk | contribs) (→Methods) |

||

| (43 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| - | + | = Background = | |

While in vivo analysis is invaluable, computational modeling can help direct experiments in a way that conserves time and resources. Current in silico models often rely on flux balance analysis (FBA) as an optimization algorithm. FBA provides a method for tracking fluxes within a biological system and “analyz[ing] biological networks in a quantitative manner” [1]. A flow chart of FBA methodology is depicted in Figure 1 [1]. | While in vivo analysis is invaluable, computational modeling can help direct experiments in a way that conserves time and resources. Current in silico models often rely on flux balance analysis (FBA) as an optimization algorithm. FBA provides a method for tracking fluxes within a biological system and “analyz[ing] biological networks in a quantitative manner” [1]. A flow chart of FBA methodology is depicted in Figure 1 [1]. | ||

[[File:FBAflowchart.jpg]] | [[File:FBAflowchart.jpg]] | ||

| - | FBA begins with the construction of an often complex biological network. After accounting for all | + | FBA begins with the construction of an often complex biological network. After accounting for all reactions within a system, FBA involves the construction of a stoichiometric matrix (N) where each column corresponds to a chemical reaction within the system and each row a molecular species. The matrix is then multiplied by a vector of internal and exchange fluxes (v), shown in Equation 1. |

| + | {1} dx/dt = Nv | ||

| + | Since FBA is a static model, we assume a steady-state and therefore Equation 2, applies. The overall equation simplifies to Equation 3. | ||

| + | {2} dx/dt = 0 | ||

| + | {3} Nv = 0 | ||

| + | Constraints are applied to the stoichiometric matrix to limit the number of possible solutions. These constraints often depend on the uptake rate and availability of nutrients within the media in which the cells are growing. A cell cannot take in a substrate if it is not available within its environment. After determining the constraints, an objective is defined, such as maximized protein production or maximized cell growth. Then, the fluxes that maximize the objective are mathematically calculated [1]. | ||

| - | + | = Methods = | |

| - | + | The modeling project began with an existing metabolic network for the MG1655 strain of E. coli (see Appendix). This model was obtained through the in silico organism database of Professor Bernard Palsson, University of California: San Diego [2]. The alkane producing reactions were then added to the metabolic network. These reactions were simplified (see below) for the FBA system in order to minimize the number of new metabolites, and thus minimize the number of dead ends in the network. In particular, we only considered the major C16 alkane product in the model. The simplified reactions are: | |

| - | |||

| - | + | [[File: Doood.png]] | |

| - | |||

| - | == | + | To then limit the number of solutions, constraints were applied to the system. The first of which concerned the uptake rate of glucose. For this value, we referred to a PNAS article, where researchers had already determined the needed rate for E. coli cells growing in a similar media [3]. Then, using the exact media composition used for this process, the exchange rate of thiamine between the extracellular space and the cytoplasm was adjusted such that the uptake rate of glucose by mass was equal to the uptake of thiamine by mass. Linear programming, the optimization process used by FBA, was then applied to determine the solution of fluxes for this system. For this process we used the COBRA Toolbox, which is a MATLAB application for FBA [4]. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | With the model working, the next step was to apply modifications to optimize alkane production. Initial data showed that with the objective of the cell being growth, the in silico fluxes through the alkane producing pathway were zero. We propose that this observation could be explained in one of two ways. The hydrophobic nature of the alkane means that it makes its way out of the cell into the surrounding media and therefore does not contribute to biomass, the overall objective we used. Also, both reactions we added rely on NADPH therefore it is possible that the model is unable to account for the additional use of NADPH and predicts a zero alkane flux. This zero flux may also be due to the scale set by the biomass function. The growth of the cell, compared to the production of alkane, is very large. Since this system is centered about growth, the FBA algorithm may consider the flux through the alkane producing pathway insignificant. This observation resulted in all following modifications focusing on maximizing production of Acyl-ACP to thus increase the probability of the metabolites entering the alkane producing pathway. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | To investigate these problems further we used GDLS, a MATLAB function that suggests possible gene knockouts to maximize a certain flux [4]. We used this technique to determined which knockouts would optimize production of Acyl-ACP. This work proposed the deletion of gene B1249, which encodes for cardiolipin synthase 1. The in silico deletion of this gene forced reactions that involved catabolizing of Acyl-ACP into smaller carrier proteins to zero (see Appendix for the raw data). The deletion also significantly decreased the biomass function, which suggests further revisions should be made. However, this is a '''prediction''' can could be tested in the future. | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Future Modifications = | ||

| + | |||

| + | While some preliminary in silico data was acquired, this model requires revisions, such as further integration of the alkane producing pathway into the existing network. One possibility is to modify the existing model by using other variants that have been published to investigate whether redox limitation is an issue. Also, significant testing of this system, in particular using C13 tracers to actually determine the fluxes internal to the cell, could test the accuracy of this model. With the needed adjustments made more predictive suggestions for maximizing alkane production could be constructed and thus a better product could be made in vivo. Overall, while the model has not yet significantly affect experimental design, it points the way towards new experiments that would help improve our understanding and increase aklane production. | ||

| + | |||

| + | = References = | ||

| + | |||

| + | [1] J. M. Lee, E. P. Gianchandani, and J. A. Papin, “Flux balance analysis in the era of metabolomics,” Briefings in bioinformatics, vol. 7, 2006, pp. 140-50. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [2] Orth, Jeff. "In Silico Organisms - Systems Biology Research Group." Systems Biology Research Group :: UCSD. Web. 28 Oct. 2011. <http://gcrg.ucsd.edu/In_Silico_Organisms>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [3] Causey, T. B., K. T. Shanmaugam, L. P. Yomano, and L. O. Ingram. "Engineering Escherichia Coli for Efficient Conversion of Glucose to Pyruvate." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101.8 (2004): 2235-240. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [4] S. A. Becker et al., “Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA Toolbox,” Nature Protocols, 2(3), 2007, pp. 727-738. | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Appendix = | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. E. Coli metabolic network [[Media: Ec_iJR904_GlcMM.txt]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. MATLAB code for FBA [[Media: Matlab_Script.m]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. Solution: all fluxes '''without''' gene knock out [[Media: allFluxes.txt]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4. Solution: nonzero fluxes '''without''' gene knock out [[Media: nonzeroFluxes.txt]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | 5. Solution: all fluxes '''with''' gene knock out [[Media: allFluxes_geneKnockout.txt]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | 6. Solution: nonzero fluxes '''with''' gene knock out [[Media: nonzeroFluxes_geneKnockout.txt]] | ||

Latest revision as of 02:25, 29 October 2011

Background

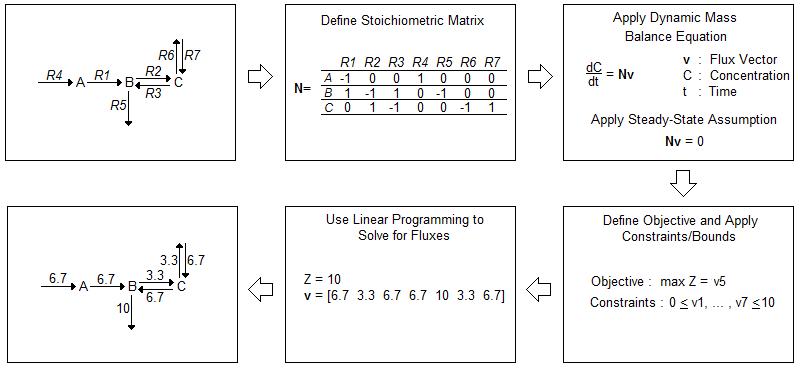

While in vivo analysis is invaluable, computational modeling can help direct experiments in a way that conserves time and resources. Current in silico models often rely on flux balance analysis (FBA) as an optimization algorithm. FBA provides a method for tracking fluxes within a biological system and “analyz[ing] biological networks in a quantitative manner” [1]. A flow chart of FBA methodology is depicted in Figure 1 [1].

FBA begins with the construction of an often complex biological network. After accounting for all reactions within a system, FBA involves the construction of a stoichiometric matrix (N) where each column corresponds to a chemical reaction within the system and each row a molecular species. The matrix is then multiplied by a vector of internal and exchange fluxes (v), shown in Equation 1.

{1} dx/dt = Nv

Since FBA is a static model, we assume a steady-state and therefore Equation 2, applies. The overall equation simplifies to Equation 3.

{2} dx/dt = 0

{3} Nv = 0

Constraints are applied to the stoichiometric matrix to limit the number of possible solutions. These constraints often depend on the uptake rate and availability of nutrients within the media in which the cells are growing. A cell cannot take in a substrate if it is not available within its environment. After determining the constraints, an objective is defined, such as maximized protein production or maximized cell growth. Then, the fluxes that maximize the objective are mathematically calculated [1].

Methods

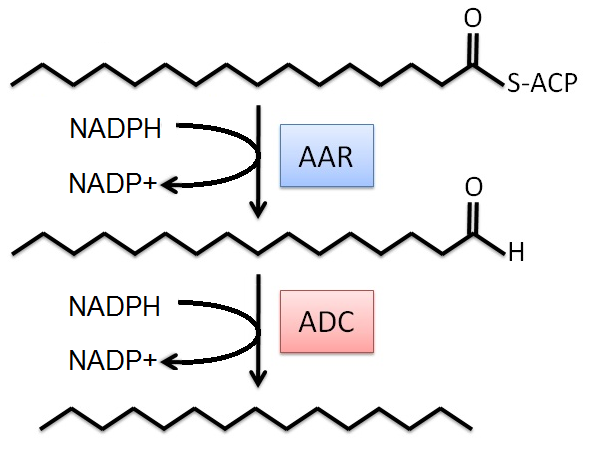

The modeling project began with an existing metabolic network for the MG1655 strain of E. coli (see Appendix). This model was obtained through the in silico organism database of Professor Bernard Palsson, University of California: San Diego [2]. The alkane producing reactions were then added to the metabolic network. These reactions were simplified (see below) for the FBA system in order to minimize the number of new metabolites, and thus minimize the number of dead ends in the network. In particular, we only considered the major C16 alkane product in the model. The simplified reactions are:

To then limit the number of solutions, constraints were applied to the system. The first of which concerned the uptake rate of glucose. For this value, we referred to a PNAS article, where researchers had already determined the needed rate for E. coli cells growing in a similar media [3]. Then, using the exact media composition used for this process, the exchange rate of thiamine between the extracellular space and the cytoplasm was adjusted such that the uptake rate of glucose by mass was equal to the uptake of thiamine by mass. Linear programming, the optimization process used by FBA, was then applied to determine the solution of fluxes for this system. For this process we used the COBRA Toolbox, which is a MATLAB application for FBA [4].

With the model working, the next step was to apply modifications to optimize alkane production. Initial data showed that with the objective of the cell being growth, the in silico fluxes through the alkane producing pathway were zero. We propose that this observation could be explained in one of two ways. The hydrophobic nature of the alkane means that it makes its way out of the cell into the surrounding media and therefore does not contribute to biomass, the overall objective we used. Also, both reactions we added rely on NADPH therefore it is possible that the model is unable to account for the additional use of NADPH and predicts a zero alkane flux. This zero flux may also be due to the scale set by the biomass function. The growth of the cell, compared to the production of alkane, is very large. Since this system is centered about growth, the FBA algorithm may consider the flux through the alkane producing pathway insignificant. This observation resulted in all following modifications focusing on maximizing production of Acyl-ACP to thus increase the probability of the metabolites entering the alkane producing pathway.

To investigate these problems further we used GDLS, a MATLAB function that suggests possible gene knockouts to maximize a certain flux [4]. We used this technique to determined which knockouts would optimize production of Acyl-ACP. This work proposed the deletion of gene B1249, which encodes for cardiolipin synthase 1. The in silico deletion of this gene forced reactions that involved catabolizing of Acyl-ACP into smaller carrier proteins to zero (see Appendix for the raw data). The deletion also significantly decreased the biomass function, which suggests further revisions should be made. However, this is a prediction can could be tested in the future.

Future Modifications

While some preliminary in silico data was acquired, this model requires revisions, such as further integration of the alkane producing pathway into the existing network. One possibility is to modify the existing model by using other variants that have been published to investigate whether redox limitation is an issue. Also, significant testing of this system, in particular using C13 tracers to actually determine the fluxes internal to the cell, could test the accuracy of this model. With the needed adjustments made more predictive suggestions for maximizing alkane production could be constructed and thus a better product could be made in vivo. Overall, while the model has not yet significantly affect experimental design, it points the way towards new experiments that would help improve our understanding and increase aklane production.

References

[1] J. M. Lee, E. P. Gianchandani, and J. A. Papin, “Flux balance analysis in the era of metabolomics,” Briefings in bioinformatics, vol. 7, 2006, pp. 140-50.

[2] Orth, Jeff. "In Silico Organisms - Systems Biology Research Group." Systems Biology Research Group :: UCSD. Web. 28 Oct. 2011. <http://gcrg.ucsd.edu/In_Silico_Organisms>.

[3] Causey, T. B., K. T. Shanmaugam, L. P. Yomano, and L. O. Ingram. "Engineering Escherichia Coli for Efficient Conversion of Glucose to Pyruvate." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101.8 (2004): 2235-240.

[4] S. A. Becker et al., “Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA Toolbox,” Nature Protocols, 2(3), 2007, pp. 727-738.

Appendix

1. E. Coli metabolic network Media: Ec_iJR904_GlcMM.txt

2. MATLAB code for FBA Media: Matlab_Script.m

3. Solution: all fluxes without gene knock out Media: allFluxes.txt

4. Solution: nonzero fluxes without gene knock out Media: nonzeroFluxes.txt

5. Solution: all fluxes with gene knock out Media: allFluxes_geneKnockout.txt

6. Solution: nonzero fluxes with gene knock out Media: nonzeroFluxes_geneKnockout.txt

"

"