Team:UCL London/Research/MagnetoSites/Theory

From 2011.igem.org

| (3 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

<div id="content"> | <div id="content"> | ||

<h1>The Theory of Binding Sites</h1> | <h1>The Theory of Binding Sites</h1> | ||

| - | + | Studies and analysis into the characteristics of the DNA-gyrase complex in 1981 by Morrison and Cozzarelli, had revealed several consensus sequences in DNA molecules which favour the binding of gyrase and its subsequent catalysis . Their experiments involved using DNase I footprinting assays and examined the sequences of DNA fragments which were protected from restriction endonuclease digestion due to association with gyrase complex. | |

| - | |||

| - | + | These highly preferred or specific sites are known as gyrase binding sites (GBS) or strong gyrase sites (SGS) and were found to be about 280 bp in the case of the Mu phage SGS . Out of the 280 base pairs in the identified Mu SGS, approximately 130 bp wraps around the tetrameric enzyme complex in a way similar to nucleosome formation. The gyrase then continues to introduce a 4 bp staggered break in the DNA strand and alter the DNA linking number in steps of 2 per reaction (please refer to the Modelling and Theory of Supercoiliology section). | |

| - | |||

| - | + | In the in vitro pBR322 plasmid GBS study, experts identified that the preferred cleavage site for gyrase have the following consensus DNA sequence: 5’-GGCTGGATGGCCTTCCCCAT-3’ . Throughout this study, researchers also found out that the cleavage occurs specifically between the TG residues (990th nucleotide in the pBR322 plasmid) in the DNA sequence <sup>[[Team:UCL_London/Bibliography#magneto-1|[1]]]</sup>. By multiple sequence alignments and mathematical predictions, they predicted the presence of around 45 to 50 major gyrase binding sites in the entire E. coli genome. These predicted sites were later seen to play an important role in compacting the bacterial chromosomal nucleoid as well as regulating the transcription and DNA replication. However, apart from these major binding sites, there are still roughly 10,000 more of the weak binding sites, which gyrase will not normally associate unless they are present in a high enough concentration. | |

| - | The figure above is a study | + | |

| - | + | Another additional property of the GBS is revealed in bacteriophages which exploit these sequences to aid them in their replication process inside the host. For instance, the Bacteriophage Mu has a strong gyrase site in the central region of the 37.2 kbp phage genome. The ‘essential’ 147 bp sequence in this GBS is vital to the phage replication within the bacterial host . It is believed that the Mu phage DNA replication requires the phage DNA to become negatively supercoiled at specific positions within the genome upto a certain extent, which then enables DNA replication to be carried out efficiently. The introduction of this highly preferred site therefore allows the phage to ‘hijack’ the endogenous E. coli gyrase enzymes to supercoil their own DNA molecules. | |

| - | Thus, in 2011 UCL iGEM project , we have | + |  |

| + | |||

| + | This figure above is a study carried out by Pato and his colleagues which indicate the importance of the essential 147 nucleotides in the Mu-GBS <sup>[[Team:UCL_London/Bibliography#magneto-2|[2]]]</sup>. As displayed, the wild type phage can carry out replication effectively (hence higher percentage of the incorporation of radioactive tritium nucleotides) compared to the mutant which lacks the GBS, after the heat induction of the lysogens. However the above study is carried out in vitro, and an in vivo study would involve more factors and therefore it is quite difficult to understand and predict how the results might deviate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A third major GBS identified by Oram et al, was one on the pSC101 plasmid which was indicated to possess the highest affinity for binding to gyrase. This GBS site was located to be on the par region of pSC101, which is known to be responsible for ensuring stable plasmid inheritance (in the absence of selection) in a population of dividing cells <sup>[[Team:UCL_London/Bibliography#magneto-3|[3]]]</sup>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:UCL-content-GBS-theory-figure-1.jpg|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + |

According to the result displayed above, the highly efficient binding and yet lack of stimulation of supercoiling by the pSC101 GBS raised the possibility that the biological effect of gyrase at par region were purely structural. For example local changes in DNA topology due to the wrapping of DNA by gyrase may already be enough to induce the downstream effects of gyrase on pSC101 replication and partition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Subsequent studies later concluded that the key function of par was to cause a local increase in superhelical density in the origin region of pSC101, and this in turn was critical in determining the interactions of other replication and partition proteins within the origin itself <sup>[[Team:UCL_London/Bibliography#magneto-4|[4]]]</sup><sup>[[Team:UCL_London/Bibliography#magneto-5|[5]]]</sup>. However, further experiments are still necessary to address these specific questions relating to the role of gyrase function at the par region at a more detailed or molecular level. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | From the studies, it was also found that the pSC101 GBS was cleaved by gyrase much more efficiently than the pBR322 site, but plasmids with pBR322 GBS were supercoiled much better than the ones with pSC101 GBS. Nevertheless, the best supercoiling efficiency was achieved only in plasmids with the Mu GBS even with a low concentration of gyrase as indicated in the figure below <sup>[[Team:UCL_London/Bibliography#magneto-6|[6]]]</sup>.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:UCL-content-GBS-theory-figure-6.jpg|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Thus, in 2011 UCL iGEM project, we have studied the usage of such sites to improve the supercoiling consistency and quality on the target plasmids and by this method, we hope to achieve better supercoiling without interfering with the normal physiological E. coli chromosomal supercoiling which may in turn affect the growth of the bacteria. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

{{:Team:UCL_London/Template/Footer}} | {{:Team:UCL_London/Template/Footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:45, 22 September 2011

The Theory of Binding Sites

Studies and analysis into the characteristics of the DNA-gyrase complex in 1981 by Morrison and Cozzarelli, had revealed several consensus sequences in DNA molecules which favour the binding of gyrase and its subsequent catalysis . Their experiments involved using DNase I footprinting assays and examined the sequences of DNA fragments which were protected from restriction endonuclease digestion due to association with gyrase complex.

These highly preferred or specific sites are known as gyrase binding sites (GBS) or strong gyrase sites (SGS) and were found to be about 280 bp in the case of the Mu phage SGS . Out of the 280 base pairs in the identified Mu SGS, approximately 130 bp wraps around the tetrameric enzyme complex in a way similar to nucleosome formation. The gyrase then continues to introduce a 4 bp staggered break in the DNA strand and alter the DNA linking number in steps of 2 per reaction (please refer to the Modelling and Theory of Supercoiliology section).

In the in vitro pBR322 plasmid GBS study, experts identified that the preferred cleavage site for gyrase have the following consensus DNA sequence: 5’-GGCTGGATGGCCTTCCCCAT-3’ . Throughout this study, researchers also found out that the cleavage occurs specifically between the TG residues (990th nucleotide in the pBR322 plasmid) in the DNA sequence [1]. By multiple sequence alignments and mathematical predictions, they predicted the presence of around 45 to 50 major gyrase binding sites in the entire E. coli genome. These predicted sites were later seen to play an important role in compacting the bacterial chromosomal nucleoid as well as regulating the transcription and DNA replication. However, apart from these major binding sites, there are still roughly 10,000 more of the weak binding sites, which gyrase will not normally associate unless they are present in a high enough concentration.

Another additional property of the GBS is revealed in bacteriophages which exploit these sequences to aid them in their replication process inside the host. For instance, the Bacteriophage Mu has a strong gyrase site in the central region of the 37.2 kbp phage genome. The ‘essential’ 147 bp sequence in this GBS is vital to the phage replication within the bacterial host . It is believed that the Mu phage DNA replication requires the phage DNA to become negatively supercoiled at specific positions within the genome upto a certain extent, which then enables DNA replication to be carried out efficiently. The introduction of this highly preferred site therefore allows the phage to ‘hijack’ the endogenous E. coli gyrase enzymes to supercoil their own DNA molecules.

This figure above is a study carried out by Pato and his colleagues which indicate the importance of the essential 147 nucleotides in the Mu-GBS [2]. As displayed, the wild type phage can carry out replication effectively (hence higher percentage of the incorporation of radioactive tritium nucleotides) compared to the mutant which lacks the GBS, after the heat induction of the lysogens. However the above study is carried out in vitro, and an in vivo study would involve more factors and therefore it is quite difficult to understand and predict how the results might deviate.

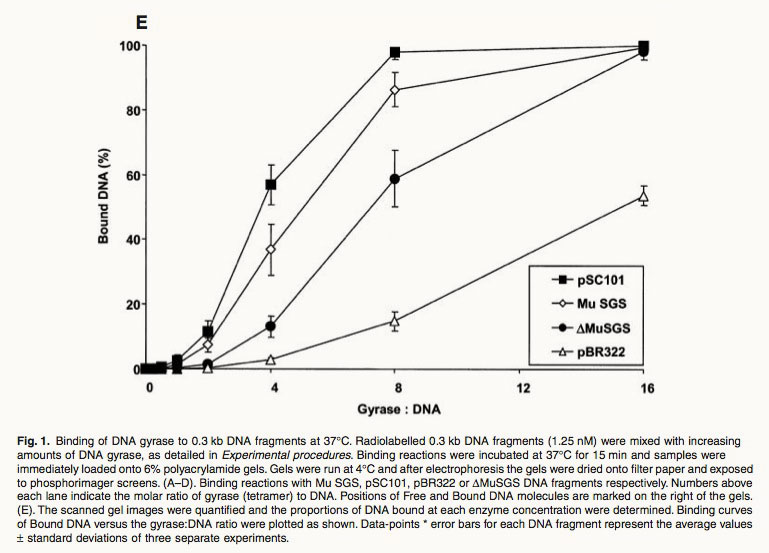

A third major GBS identified by Oram et al, was one on the pSC101 plasmid which was indicated to possess the highest affinity for binding to gyrase. This GBS site was located to be on the par region of pSC101, which is known to be responsible for ensuring stable plasmid inheritance (in the absence of selection) in a population of dividing cells [3].

According to the result displayed above, the highly efficient binding and yet lack of stimulation of supercoiling by the pSC101 GBS raised the possibility that the biological effect of gyrase at par region were purely structural. For example local changes in DNA topology due to the wrapping of DNA by gyrase may already be enough to induce the downstream effects of gyrase on pSC101 replication and partition.

Subsequent studies later concluded that the key function of par was to cause a local increase in superhelical density in the origin region of pSC101, and this in turn was critical in determining the interactions of other replication and partition proteins within the origin itself [4][5]. However, further experiments are still necessary to address these specific questions relating to the role of gyrase function at the par region at a more detailed or molecular level.

From the studies, it was also found that the pSC101 GBS was cleaved by gyrase much more efficiently than the pBR322 site, but plasmids with pBR322 GBS were supercoiled much better than the ones with pSC101 GBS. Nevertheless, the best supercoiling efficiency was achieved only in plasmids with the Mu GBS even with a low concentration of gyrase as indicated in the figure below [6].

Thus, in 2011 UCL iGEM project, we have studied the usage of such sites to improve the supercoiling consistency and quality on the target plasmids and by this method, we hope to achieve better supercoiling without interfering with the normal physiological E. coli chromosomal supercoiling which may in turn affect the growth of the bacteria.

"

"