Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Project/Background/NAD

From 2011.igem.org

Contents |

NAD+ detection

NAD+ in general

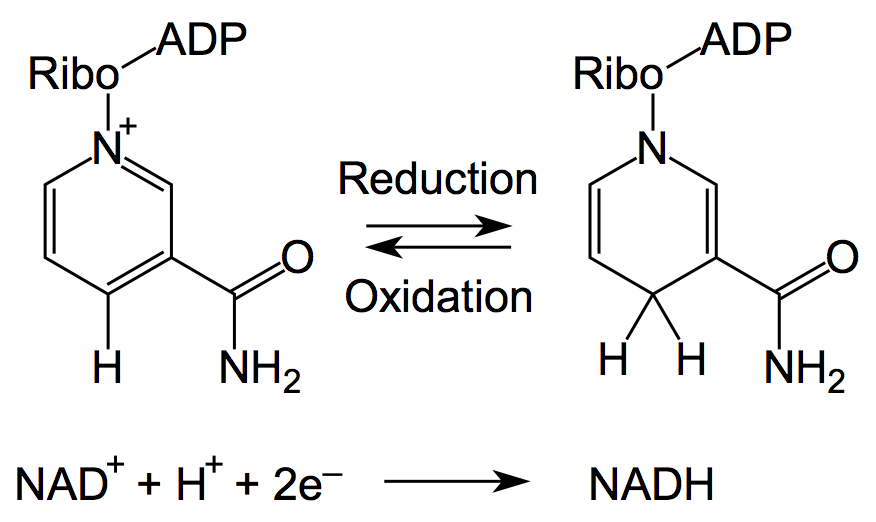

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, abbreviated NAD+, is an ubiquitous and indispensable cofactor for all living organisms (Bi et al., 2011). The molecule has a wide range of physiological functions in cellular processes and a great impact on the cell integrity (Grahnert et al., 2011). Bi et al. (2011) announced the following physiological functions for NAD(P): cellular metabolism, energy metabolism, cofactor, DNA repair, redox reaction, precursor for vitamine B12, telomere maintenance, gene silencing, cell longevity, immune response, Ca2+ signaling and regulation of incretion. Thus, NAD is integrated into the energy metabolism and determines the redox status of the cell due to its purpose as a reduction equivalent (see Figures 1 and 2). This is strongly linked to the control of signaling and transcriptional events. For instance, NAD+ has been recently described as a modulator of immune functions (Grahnert et al., 2011) and a master regulator of transcription (Ghosh et al., 2010). Several enzymes are tightly regulated by the cellular balance between the oxidized and reduced form of NAD+ and are therefore regarded as a potential target for therapeutics (Sauve, 2008). Indeed, NAD+ acts as a substrate for a wide range of proteins including NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases and several transcription factors (Houtcooper et al., 2010). An imbalance of the cellular NAD+ level has usually relevance in symptoms and diseases like stroke, cardiac ischemia, epilepsy, huntington disease, wallerian degeneration, cancer, type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM), neutrophil survival, longevity, obesity as well as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease (Sauve, 2008; Houtcooper et al., 2010). Additionally, the regulation of NAD+-dependent pathways may have an influence on oxidative metabolism and life span extension (Houtcooper et al., 2010). Because of the essentialities of DNA ligases for fundamental processes in bacterial cells, the biosynthetic pathways for NAD+ are proposed as promising novel antibiotics targets against pathogens (Bi et al., 2011).

NAD+ is embedded in the cellular metabolism and has a great impact on essential cellular processes.

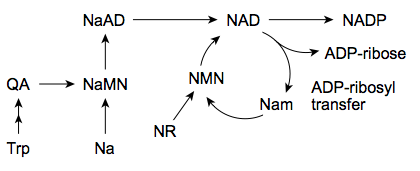

The biosynthesis in most bacteria and plants starts with the anaerobic conversion of the amino acid aspartate to quinolinic acid (QA). As indicated in Figure 3, in yeast, humans and some bacterial microbes the quinolinic acid (QA) derives from tryptophan in an aerobic manner. This is a crucial step that leads under consumption of nicotinic acid (Na) to the nicotinate ring system via formation of nicotinic acid monoculeotide (NaMN), respectively (Sauve, 2008). After conjugation of adenosine mononucleotide (AMP) the NAD synthetase forms nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD). Additionally, it has been reported recently that in humans exists an nicotinic acid-independent reaction catalysed by the enzyme nampt/PBEF, which uses nicotinamide (Nam) directly as a substrate (Rongvaux, 2002). Diet or pharmalogical agents can thereby serve as a source for nicotinamide or nicotinic acid (Sauve, 2008). Fundamental processes as the cellular energy metabolism determine the balance between the oxidized (NAD+) and reduced (NADH) form of NAD (see Figures 1 and 2).

Bacterial DNA ligases

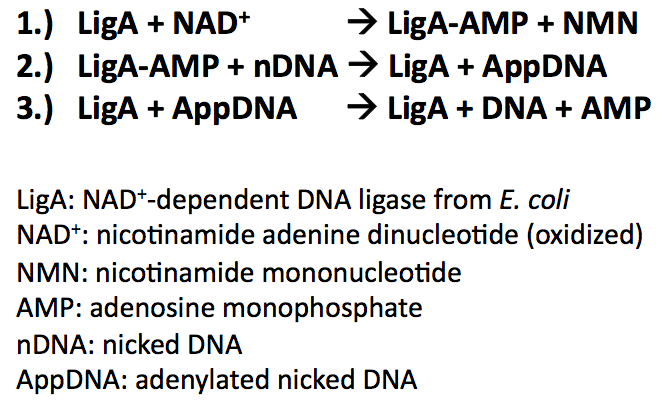

Bacterial DNA ligases are important enzymes for DNA repair and replication. The big difference between bacterial and eukaryotic DNA ligases is their specifity for cofactors. While eukaryotic DNA ligases use ATP as a source for building a phosphodiester bond in the DNAs phosphate backbone, the bacterial ones display a NAD+-dependent biochemical catalysis. These enzymes are essential for bacterial survival and are therefore in focus for designing highly specific antiinfectives (Gajiwala & Pinko, 2004). All bacterial DNA ligases possess highly conserved functional domains. Generally, they can be devided into four functionally distinguishable domains, each with characteristic motifs:

- Domain 1: Ia, Ib (NTase)

- Domain 2: Oligomer-binding (OB) beta-barrel

- Domain 3: Zinc (Zn)-finger, helix-hairpin-helix motif (HhH)

- Domain 4: BRCT domain

All bacterial DNA ligases share three fundamental steps during their reaction mechanism (Nandakumar et al., 2007):

- Adenylation of DNA ligase by transferring hydrolysed AMP from NAD+ to the active site lysine and release of NMN

- Tranfer of the AMP from DNA ligase to the 5'-phosphate group of nicked DNA

- Formation of a phosphodiester bond by attack of the nick 3'-OH on the 5'-phosphoanhydride linkage and release of free AMP

Applications of molecular beacons

Molecular beacons can be applied to a wide range of biological and diagnostical studies. Some examples for applying molecular beacons in different biological fields are described in Figures 4, 5 and 6. Whenever there is a specific nucleic acid which is supposed to be detected they can be utilized. Molecular beacons are used for the detection and distinction of retroviral DNA from different types of HIV, for instance (Marras et al., 2006). Even for identification of proteins which interact with DNA or RNA they are useful. In sum, there are a lot of opportunities to apply molecular beacons (Antony & Subramaniam, 2001):

- Detection of PCR amplification products

- Mutational analysis

- Genotyping and allele discrimination

- Clinical diagnosis

- Oligonucleotide degradation studies

- Analysis of DNA/RNA hybridization

- Realtime visualization of hybridization in cells

- Analysis of triplex DNA formation

- Protein/DNA interaction

- Enzymatic assays

- Biosensors

| Figure 4: Hybridization of the molecular beacon and a complementary target forms the molecular beacons open state which leads to an increase of the fluorescence intensity. The molecular beacon can be immmobilized using specific biomolecular interaction, e.g. streptavidin/biotin or covalent cross-linking (taken from Kim et al., 2008). | Figure 5: Single nucleotide polymorphism of nucleic acids, including different alleles as indicated, can be detected by differently designed and labeled molecular beacons (taken from Kim et al., 2008). | Figure 6: Realtime in vivo imaging of specific mRNAs utilizing two molecular beacons that target adjacent positions on the mRNA allowing FRET to take place (taken from Kim et al., 2008). |

Further applications of the NAD+ bioassay

The reviewed molecular beacon based NAD+ bioassay can be applied to biochemical and biomedical studies (Tang et al., 2011). Accordingly, it can be utilized to detect NAD+/NADH-dependent enzymatic processes. The low limit of detection, its reliability and manageability provides a practical alternative to present colorimetric, fluorometric, chemiluminescent, electrochemical or mass spectrometric methods detecting NAD+ or NADH. In context of clinical applications and therapeutics the NAD+ bioassay can be useful to monitor cellular NAD+ levels during treatments of tissues or cell cultures for identification of drug targets, for instance. It may also be applied in the field of diagnostics. Finally, the principle of the proposed NAD+ bioassay can be used for cell-free optical biosensors by taking molecular beacons either immobilized on the sensor surface or being present in the reaction medium.

References

Antony T, Subramaniam V (2001) Molecular Beacons: Nucleic Acid Hybridization and Emerging Applications, Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics 19(3):497-504.

Bi J, Wang H, Xiel J (2011) Comparative genomics of NAD(P) biosynthesis and novel antibiotic drug targets, Journal of Cellular Physiology 226(2):331-340.

Gajiwala KS, Pinko C (2004) Structural Rearrangement Accompanying NAD+ Synthesis within a Bacterial DNA Ligase Crystal, Structure 12(8):1449-1459.

Ghosh S, George S, Roy U, Ramachandran D, Kolthur-Seetharam U (2010) NAD: A master regulator of transcription, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1799(10-12):681-693.

Grahnert And, Grahnert Anj, Klein C, Schilling E, Wehrhahn J, Hauschildt S (2011) NAD+: A modulator of immune functions, Innate Immunity 17(2):212-233.

Houtkooper RH, Cantó C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J (2010) The Secret Life of NAD+: An Old Metabolite Controlling New Metabolic Signaling Pathways, Endocrine Reviews 31(2):194-223.

Kim Y, Sohn D, Tan W (2008) Molecular Beacons in Biomedical Detection and Clinical Diagnosis, International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 1:105-116.

Marras SA, Tyagi S, Kramer FR (2006) Real-time assays with molecular beacons and other fluorescent nucleic acid hybridization probes, Clinica chimica acta 363(1-2):48-60.

Miesel L, Kravec C, Xin AT, McMonagle P, Ma S, Pichardo J, Feld B, Barrabee E, Palermo R (2007) High-throughput assay for the adenylation reaction of bacterial DNA ligase, Analytical Biochemistry 366:9-17.

Nandakumar J, Nair PA, Shuman S (2007) Last Stop on the Road to Repair: Structure of E. coli DNA Ligase Bound to Nicked DNA-Adenylate, Molecular Cell 26(2):257-271.

Rongvaux A, Shea RJ, Mulks MH, Gigot D, Urbain J, Leo O, Andris F (2002) Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, whose expression is up-regulated in activated lymphocytes, is a nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, a cytosolic enzyme involved in NAD biosynthesis, European Journal of Immunology 32(11):3225-3234.

Sauve AA (2008) NAD+ and Vitamin B3: From Metabolism to Therapies, The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 324(3):883-893.

"

"