Team:Calgary/Project/Chassis/Pseudomonas

From 2011.igem.org

A Chassis Using Native Tailings Pond Species

A Pseudomonas Conjugation System

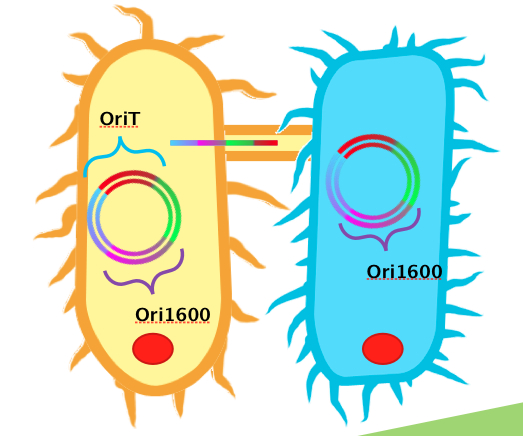

In order to use Pseudomonas spp. as an effective platform for sensing naphthenic acids, our team recognized that we would need it to take up our biosensor plasmid construct with high efficiency. To do this, we decided to design a conjugation system, capable of conjugating plasmids from E. coli to Pseudomonas spp. In order for conjugation to occur, the necessary plasmid DNA must already be inserted into E. coli. A unique sequence recognizable by relaxase and nickase called oriT (origin of transfer), must be coded into the plasmid. Additionally, the plasmid requires replication origins for both E. coli (such as ColE1) and Pseudomonas spp. (such as ori1600). Ori1600, which we used in our system, is a replication-stabilizing element for Pseudomonas spp., and requires ColE1 to function. All other enzymes required for conjugation are available in the receptor Pseudomonas species.

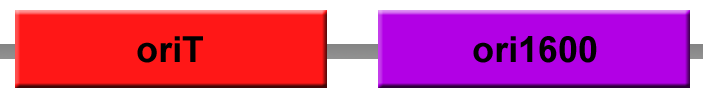

We obtained DNA for both oriT and ori1600, BioBricked them and have submitted them as BioBrick parts. Using BioBrick cloning, we put these two elements together on a single plasmid to make a testing construct. Already present in the registry is an oriT part J01003, which was characterized by Heidelberg in 2008. This part was used for conjugation between strains of E. coli. Theoretically, this part could also be used for conjugation between Pseudomonas and E. coli. Based on the sequences however, we hypothesized that our oriT, which is considerably longer, may have additional regions to improve efficiency in conjugating to Pseudomonas. To test this, we built additional constructs using J01003 and our ori1600 part to compare to our oriT- ori1600 construct.

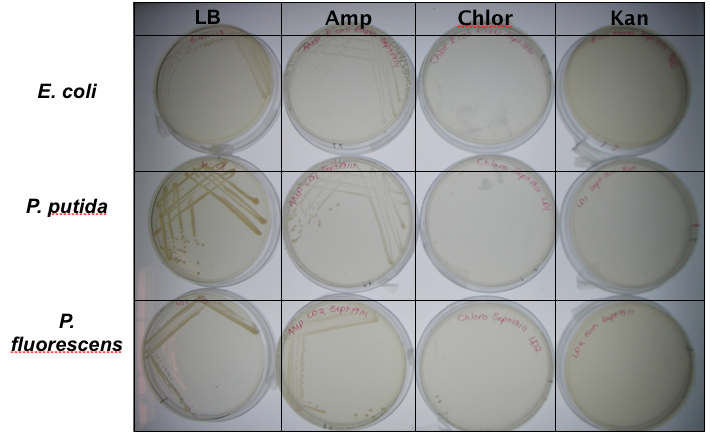

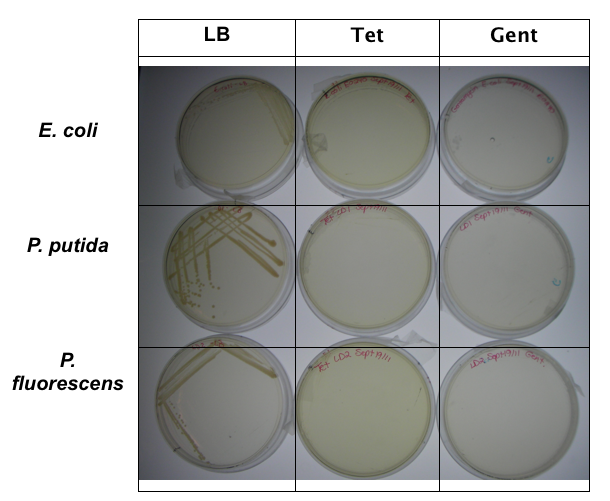

In order to test that our constructs were working, we needed a selective marker. We performed a growth assay on our Pseudomonas strains, verifying if they can grow on different antibiotics. Pseudomonas was streaked on LB agar plates containing no antibiotics, tetracycline (25 ug/ml), chloramphenicol (35 ug/mL), kanamycin (50 ug/mL), ampicillin (100 ug/mL) and gentamyacin (50 ug/mL). Growth was observed on LB alone as well as on ampicillin, indicating that Pseudomonas, as expected, is naturally resistant to ampicillin. The lack of growth on the other antibiotics, however, indicated that resistance markers for these could possibly be used to test out the functionality of our constructs.

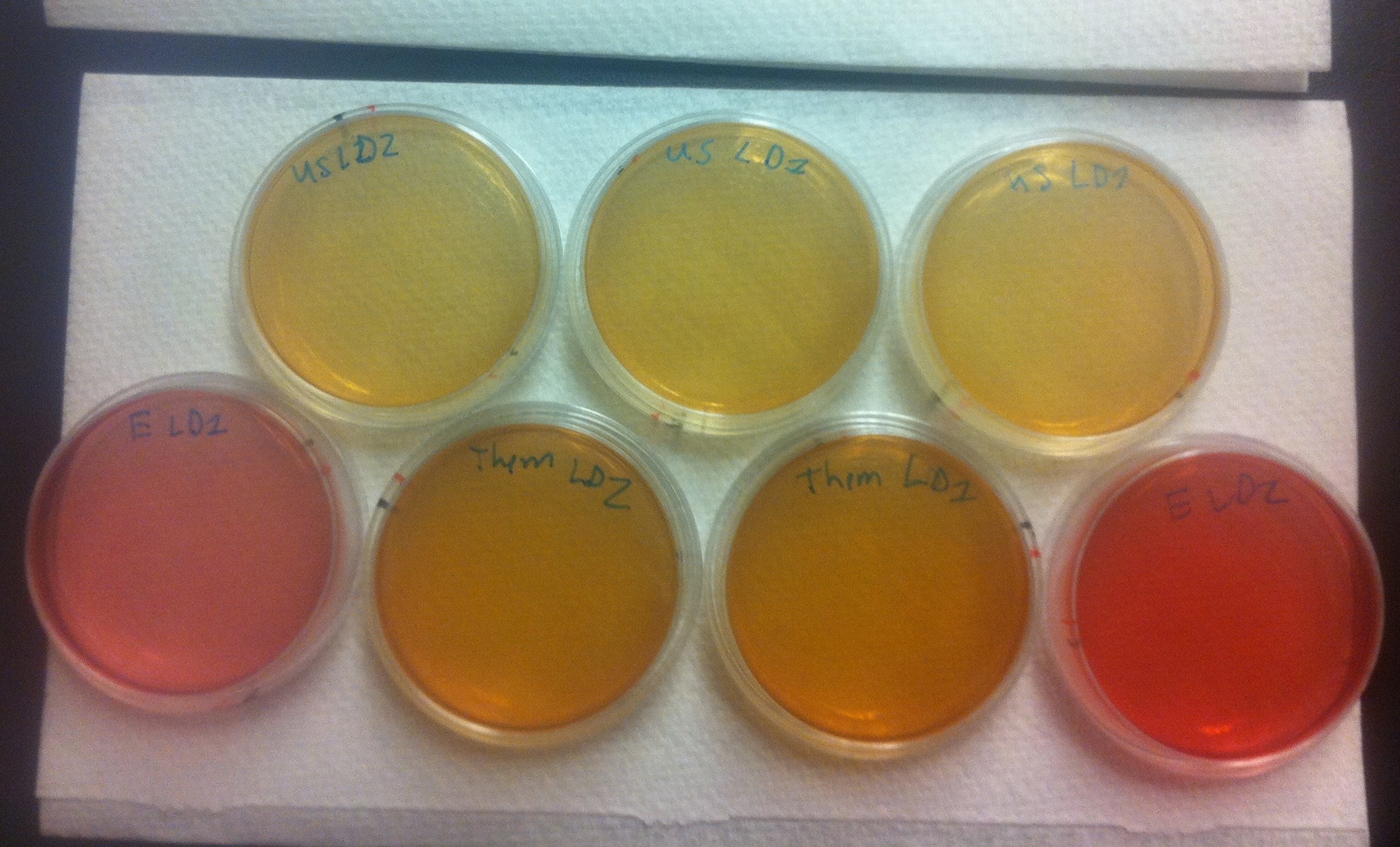

Based on this, we moved our constructs into tetracycline and kanamycin resistance vectors for testing. Colonies of E.Coli containing our plasmids were used to innocluate 5 mL LB cultures with kanamycin-50 and tetracycline-25. 100 μL of our two Pseudomonas strains were added and cultures were shaken in a 26°C incubator. OD readings of cultures were taken to standardize cell counts and cultures were then plated on MacConkey agar plates. MacConkey agar, which has a reddish-purple color, is able to distinguish between bacteria that can and cannot metabolize lactose via a color change. Bacteria that do not metabolize lactose, such as Pseudomonas, use peptone instead and reduce ammonia, which causes a yellow color change of the plates due to an increase in pH. E. coli, on the other hand, do metabolize lactose, and therefore no color change is seen.

Characterization

Functionality Test

In our first assay, we wanted to see that our BBa_K640004 (oriT-ori1600) construct was working. We incubated the co-cutures for 12 hours at 37°c prior to plating. The plates were then left to grow overnight.Results

The large plates on the right show controls of Pseudomonas and E. coli on MacConkey plates indicating the normal expected colors for these organisms. The small plates on the bottom represent our construct, conjugated with two different strains of pseudomonas and plated on MacConkey agar with Kanamycin (50ug/mL). The yellow color indicates that the colonies are Pseudomonas. The small plates on the top show our two strains of Pseudomonas, as well as E. coli without kanamycin resistance plated on MacConkey agar plates with kanamycin (50 ug/mL). All of these plates are pink in color, and show no colonies. This was expected, as it shows that without a resistance marker, these organisms are not able to grow on the MacConkey kanamycin plates. This demonstrates that our part is working the way we expect it to!

Time Assay

Once we had demonstrated that our part was working, we went on to try to determine how long it would take for the conjugation to occur. We experimented with different incubation times of the co-cultures at 37° before plating. We tried incubating after 10 minutes, 2 hours, 6 hours and 12 hours.Results

The table below shows the colonie counts that we recorded after each interval. Counts are the average of two repeats.Incubation |

Average # |

10 min |

0 |

2 hrs |

2 |

6 hrs |

4.5 |

12 hrs |

150 |

Comparison between BBa_K640004 and BBa_K640005

As we mentioned before, there is an existing oriT in the registry (BBa_J01003), that the 2008 Heidelberg team had previously characterized in 2008 for the conjugation of plasmids in E. coli. This is the OriT that is present in our BBa_K640006 construct, which contains the oriT and our ori1600 (BBa_K640003). We had hypothesized that our OriT, given its longer sequence, may contain elements that improve the efficiency of conjugation to Pseudomonas spp. To test this, we did an assay using E. coli conatining our BBa_K640004 part (which contains our oriT: BBa_K640002 and BBa_K640003) as well as E. coli containing BBa_K640006. We used a simpler conjugation assay, adapted from Serna et al., 2010. Overnight cultures of the donor and the recipient were prepared in LB medium. Aliquots of 500 μl were mixed to obtain a donor/recipient ratio of 1:1. Each mixture was centrifuged to pellet the cells, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were resuspended in 50 μl of LB broth. Mating mixtures were incubated at 37° for 4 h. Diluted and undiluted aliquots were then spread on selective plates.Results

The image below shows our results. On the top, E. coli cells containing the BBa_K640004 construct (which contains our oriT) were used. On the bottom row, on either end, we see plates where E. coli cells containing a kanamycin resistant plasmid, but no OriT or ori1600 construct were used. These are pink in color, with no cells growing,indicating that Pseudomonas and E. coli are not able to naturally conjugate plasmids without our part. In the middle of the bottom row, we see plates where E. coli cells containing the BBa_K640005 construct was used (where we use the registry oriT with our ori1600). As we can see, the plates with the BBa_K640004 are much lighter in color, than the plates where the BBa_K640005 construct was used. This is indicative that there is increased pseudomonas growth, when we use our oriT, as compared to the registry oriT. This was exactly what we had expected, and we hope to have more quantitative data in the next few weeks!

Quantitation

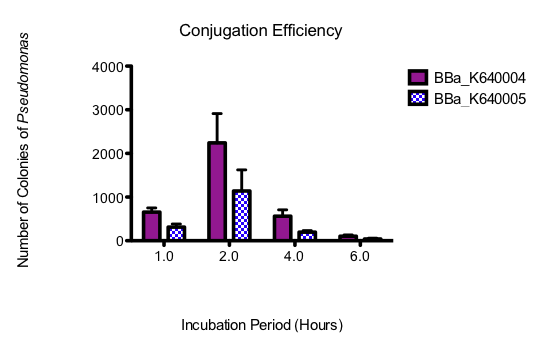

After showing qualitatively that our system was working, the next step was to get some quantitative data. Our preliminary results indicated that our oriT (BBa_K640003) was more effective at conjugating plasmids from Pseudomonas to E. Coli than the oriT already in the registry (BBa_J01003). We wanted some quantitative results to support this however. The easiest way to do this would be to perform a colony count of pseudomonas colonies after conjugation co-cultures.In order to make it easy to eliminate E. Coli colonies, we originally tried plating conjugation mixtures on AK plates, as our previous assays had shown that our environmental pseudomonas isolates are indeed naturally resistant to ampicillin, while E. Coli is not. This however resulted in no growth whatsoever. We hypothesized that given that Pseudomonas already have less than optimal growth on MacConkie agar, perhaps the added stress of two different antibiotics was too much. We went back to plating on kanaymcin, and performing oxidase tests on indivdual colonies. Pseudomonas putida and Psuedomonas fluoresceins are also known to fluoresce on MacConkie agar under UV light, so this was also used as verification.

The following protocol was used: E. Coli cultures containing constructs with our oriT and Ori1600 (BBa_K640004) and the existing oriT and Ori1600(BBa_K640005) as well as pseudomonas cultures were grown overnight to an OD of around 0.6. OD readings were taken, and co-cultures of pseudomonas and E. Coli were set up, using OD ratios to standardize for the number of cells, using approximately 300 uL of each culture. These co-cultures were spun down, resuspended in 50 uL of LB broth, and incubated at 37 C for different periods of time (30 minutes, 1h, 2h, 4h and 6h and 8h). After incubation, cultures were diluted, and then plated on MacConkie agar with kanamycin.

The assay needed to be optimized such that appropriate dilutions were used to isolate individual colonies as several original assays ether showed lawns of growth, or no growth at all. The optimal dilution was determined to be 10^-6. Results for the optimized assay are shown below. Colony counts were taken by dividing the plate into 8, counting colonies in one section and then multiplying by 8. Counts were done by two individuals and the average of the two was taken. The assay was done in triplicate and graphed showing standard error bars. The 30 minute time point was not included on the graph, as the colonies, although plentiful at this time point, were determined through fluorescence analysis and oxidase tests to be E. Colony. All subsequent time points were determined to be pseudomonas. The 8 hour time point was also not graphed, as no growth was observed for wither construct.

Conclusions

From this data, it seems that our part is indeed allowing for more efficient conjugation to pseudomonas than the existing part. The optimum incubation time appears to be 2 hours, as above that, colony counts trail off. Colony counts were taken 12 hours after the final plating. Growth beyond 6 hours was not noted. This could have been because these cells had had less time to grow. On that note however, not only does our part seem to produce more pseudomonas colonies with the plasmid, but the conjugation seems to occur quicker, as there was substantially more growth at 4 h, and there was also small amounts of growth at 6h, where none was seen for the other construct.Taken together, these results have allowed us to show that not only does our system work but that t is quicker and more efficient than what is currently fond in the registry. Most importantly however, the large amount of Pseudomonas growth suggests that this system will be appropriate for moving our final system into pseudomonas. A testing construct containing our conjugation device (BBa_K640004) downstream of our putative NA-response element (BBa_K640008) and lacZ (BBa_I732019) was built, biobricked and submitted to the registry (BBa_K640006) however due to time constraints no functional conjugation assays were able to be performed.

"

"