Team:MIT/Project/

From 2011.igem.org

Project Description

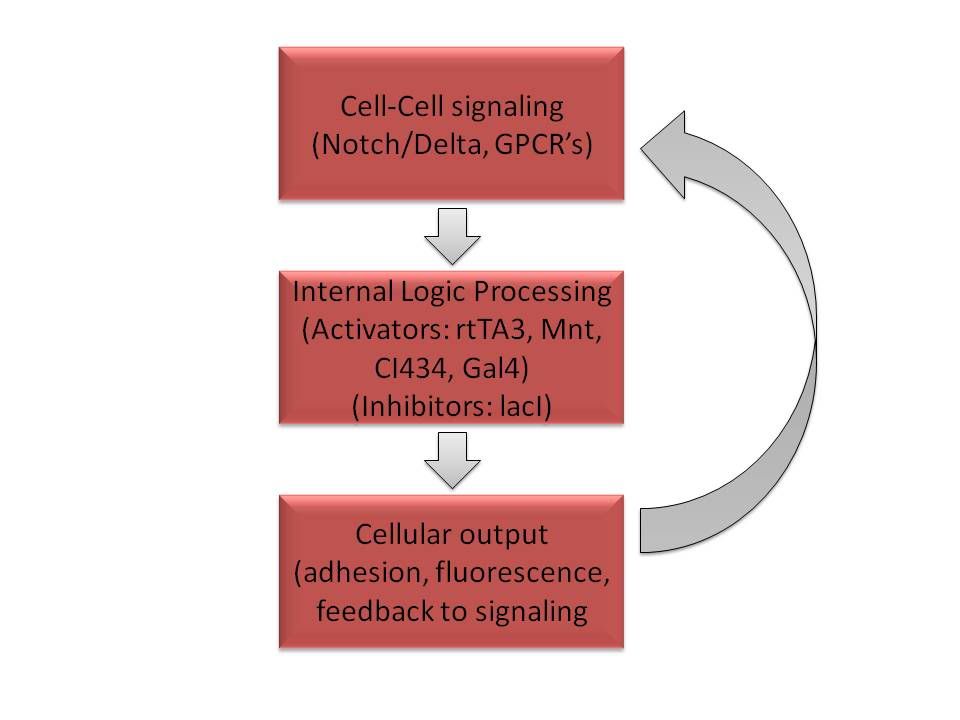

Current medical practices are only able to scratch the surface of tissue engineering or organ development. Fortunately, nature has provided us with robust, cellular systems capable of governing the autonomous formation of complex structures. To pursue control of multicellular systems, we engineered a number of ligand-receptor signaling mechanisms: the Notch-Delta juxtacrine signaling pathway and an assortment of G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). Both signaling systems were modified to feed into introduced orthogonal molecular circuits. This allows a number of signals to be processed logically. Finally, in order to hold our cells together to maintain pattern formation, we introduced cadherin, a natural intercellular glue. To understand and predict multicellular behavior, we developed a simulation framework based on the Synthetic Biology Open Language (SMOL) and CompuCell 3D modelling environment. Our models motivated several circuit designs we subsequently tested in the laboratory. Altogether, our developments establish a paradigm for manipulation of intercellular communication systems to drive self-assembly of ever more complex patterns and tissues.

A hallmark of higher order organisms is the development of multi-cellular structures such as tissues and organs from individual single-cell level interactions. A heart starts as a collection of generic cells but eventually these cells decide to become muscle, nerves, and blood cells that allow the heart to acquire the correct higher order structure and become functional. The fate of these undifferentiated cells is determined by intricate cell communication.

Currently, naturally occurring receptor-ligand interactions and sensing mechanisms are just becoming characterized. However, most existing multi-cellular self-assembly systems have utilized cues provided by an external source. This year, the MIT iGEM team is creating an autonomous system capable of self-assembly of multi-cellular structures. These systems will examine the environment using receptor-mediated communication, make a decision to choose a certain cell-state, and create a variety of patterned structures.

Specifically, we aim to construct a modular system involving juxtacrine cell signaling and G-protein coupled receptors. This will allow us to engineer interchangeable circuit responses using Mammalian BioBricks to inflammatory, cancerous, or infectious cues, leading to applications in tissue engineering, immunology responses, and cell patterning. Our efforts thus far are focused on demonstrating complex cell patterning and signal propagation through a population of cells, and we hope that our work will unlock a new realm of possibilities for the synthetic biology community and future iGEM teams. The ability to program cells to self-organize through inter-cell communication would be a groundbreaking advancement for synthetic biology. We would create an autonomous system, independent of artificial scaffolding or guidance, a true mimicry of natural organogenesis.

Device Designs

Elowitz Sender

In this circuit, found in the "receiver" type CHO cells from Elowitz, CMV-TO is normally inhibited by TetR. This inhibition itself is inhibited by doxycycline binding to TetR. In this way, we can turn on expression of Delta-mCherry with dox in a modulated fashion Elowitz Receivers

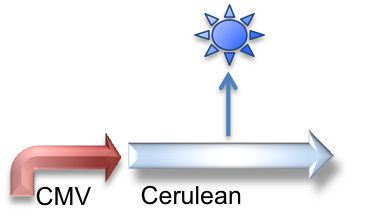

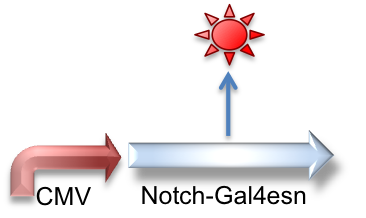

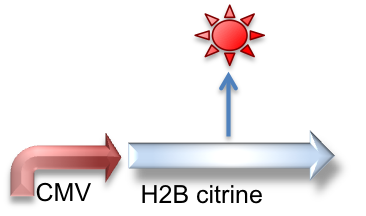

These genetic constructs have been stably integrated into our "receiver" type Elowtiz CHO cells. CMV (from the cytomegalovirus) is a strong constitutive promoter that will express Cerulean (a cyan fluorescent protein) and Notch. When Notch is bound by Delta, the Gal4esn is cleaved off and can activate expression of genes downstream of UAS.

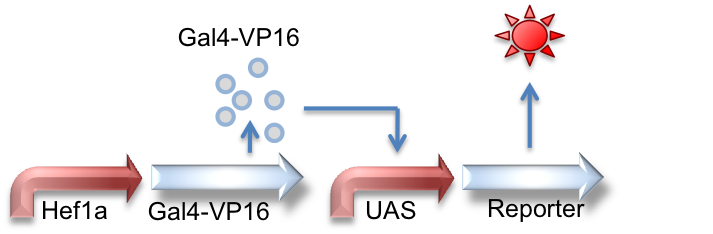

Hef1a:Gal4-VP16, UAS:Reporter

This circuit represents the behavior of the Gal4 activator. Hef1a is a constitutive promoter that will express Gal4-VP16 that can later bind to a UAS promoter, leading to the expression of downstream reporter genes.

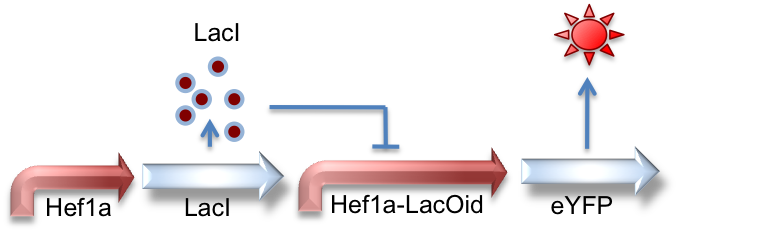

Hef1a:LacI, Hef1a-LacOid:eYFP

Here we represent the activity of the LacI inhibitor. LacI binds to the upstream LacO site and can inhibit expression of downstream reporter genes.

Hef1a:Gal4-VP16, UAS:LacI, Hef1a-LacOid:eYFP

Here we see a circuit that integrates the two systems described above. By tying LacI expression to the Gal4/UAS system, we can activate expression of lacI by GV16 and thus inhibit expression of a reporter gene. This results in overall repression of reporter expression.

Hef1a:rtTA3, TRE:Mnt-VP16, minCMV-4xMnt:mKate

Here we represent a circuit that has an upstream rtTA3 system feeding into the Mnt activator system. When bound by doxycycline, rtTA3 is capable of inducing expression at the TRE promoter. This in turn leads to expression of the activator Mnt-VP16 which can bind to Mnt sites and activate expression of the reporter gene (mKate, a red fluorescent protein, in this case).

Hef1a:rtTA3, TRE:CI434-VP16, minCMV-1xCI434:mKate

This circuit is very similar in design to the above, instead using a different orthogonal activator-promoter pair: CI434. In this schematic, doxycycline induced expression of CI434 leads to activation of reporter expression downstream of the CI434 binding site (minCMV-1xCI434).

Safety

Would any of your project ideas raise safety issues in terms of:

- researcher safety,

- public safety, or

- environmental safety?

This summer, our team worked on cell patterning in mammalian cells. Part of our team worked with E. Coli in a BL1 lab, and a smaller group worked with mammalian cells in a BL2 lab. Both groups within the team adhered to national and local safety protocols. Extra care was taken not to cross-contaminate lab spaces. Cross contamination from these settings was minimized by designating specific equipment for mammalian cells and for bacteria, as well as immediately changing personal protective equipment when moving between the different lab spaces.

Do any of the new BioBrick parts (or devices) that you made this year raise any safety issues? If yes,

- did you document these issues in the Registry?

- how did you manage to handle the safety issue?

- how could other teams learn from your experience?

Our bacteria and our mammalian cells do not contain any BioBrick parts that code for hazardous proteins or molecules. We also determined that none of our circuits would survive if released outside the lab and thus, the circuits pose no safety concerns to researchers, the public, or the environment.

Is there a local biosafety group, committee, or review board at your institution?

- If yes, what does your local biosafety group think about your project?

The EHS (Environment, Health, and Safety) Office is MIT's biosafety group that enforces lab safety in all labs on campus. They provide safety training, waste management services, and resources for safe lab practices. The safety training included General Biosafety for Researchers, Managing Hazardous Waste, General Chemical Hygiene, lab-specific training, and Bloodborne Pathogen Training. All undergraduates were trained by the EHS to work safely in BL1 labs, and students working with mammalian cells received BL2 lab safety training. EHS is an integral part of our biosafety system and continues to be involved by conducting daily lab safety inspections.

Do you have any other ideas how to deal with safety issues that could be useful for future iGEM competitions? How could parts, devices and systems be made even safer through biosafety engineering?

Our MammoBlock construction standard not only aids in the construction of mammalian parts but also facilitates safer and easier storage of these parts. The MammoBlock standard uses bacterial entry vectors which allows mammalian parts to be stored in BL1 conditions.

This standard has allowed us to enter mammalian parts into the registry, and will facilitate the safe shipping and submission of mammalian parts constructed by future iGEM teams.

Our team is also greatly concerned with the safety issues regarding future iGEM research and competitions. This prompted us to sign up to teach a class for MIT’s Educational Studies Program summer HSSP session. Our class discusses the progress Synthetic Biology has made, controversies surrounding it, current research, and biosafety precautions and concerns. By teaching this course to middle school students, we intend to get them excited about synthetic biology and to prompt them to think about their own biosafety prior to getting more intensive scientific training and experience in the lab. We hope that by exposing these children to knowledge about Synthetic Biology and Biosafety Engineering at an early age, we can inspire these future iGEMers to proactively take a central role in enhancing biosafety and security in the iGEM competition.

"

"