Team:Minnesota/Project

From 2011.igem.org

| Home | Team | Project | Software | Protocols | Notebook | Attributions | Safety |

|---|

Contents |

Introduction

E. coli Based Bionanotemplating

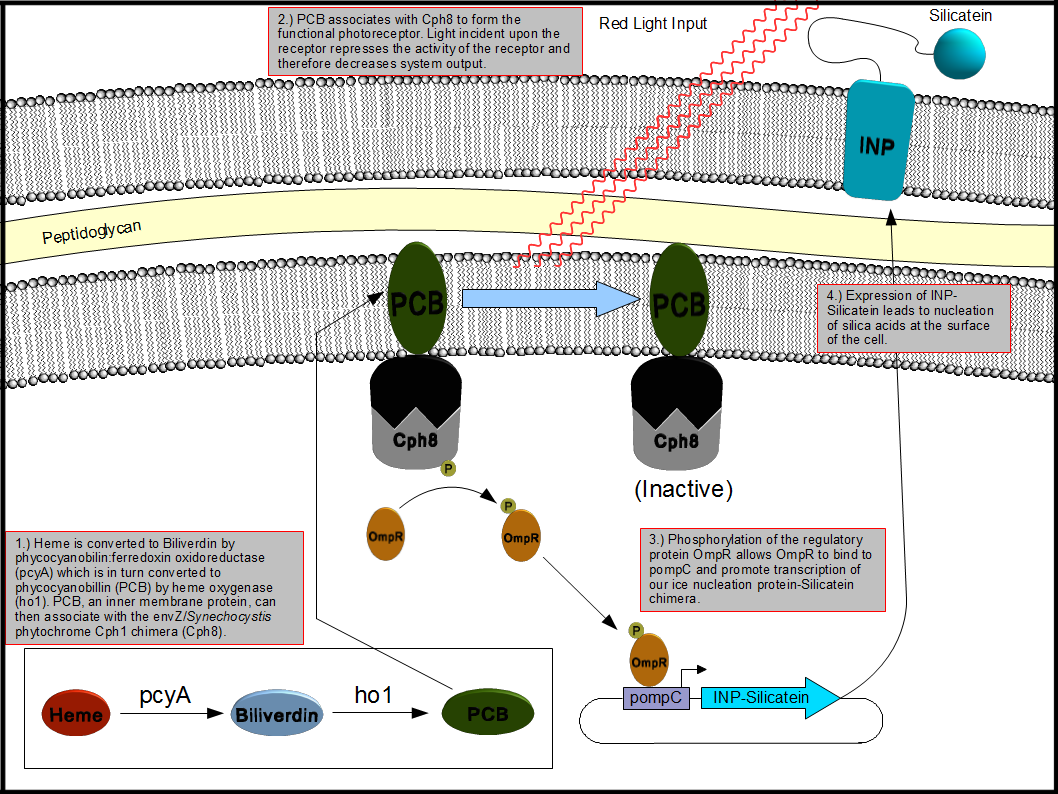

This bionanotemplating system will depend upon two components: a light inducible regulatory system and a mechanism to decorate the surface of the cell with silicatein. To accomplish this goal, out team decided to employ the Coliroid red-light sensor system first characterized by the 2004 joint University of Texas at Austin and UCSF iGEM team 5. Unfortunately we were unable to reconstitute the system from the iGEM distribution plates and so one of our projects became the reconstruction of the complete system and update the physical parts in the Standard Registry of Biological Parts. The second project we chose to work on was producing a chimeric fusion protein of silicatein with an outer membrane protein such as ompA or ice nucleation protein (INP) in order to decorate the surface of the cell with silicatein as shown below in figure 2.

Figure 2. Expression of an INP-Silicatein fusion protein in E. coli driven by the "Coliroid" induction system. Phycocyanobilin:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (pcyA), heme oxygenase (ho1), and a cph1/envZ fusion protein (Cph8) are encoded on a single plasmid. PcyA and ho1 are expressed under a arabinose responsive promoter whereas Cph8 is expressed under a tetR promoter. This arrangement allows for precise control over which genes are expressed at what time which allows us to optimize the production and assembly of the photoreceptor. Once produced, pcyA and ho1 function to convert heme into phycocyanobilin (PCB) which then associates with Cph8 to form the complete photoreceptor. Photoreceptors exposed to red light are inactivated whereas those which are not exposed to light remain active thus stimulating the production of genes under control of the pompR promoter. We placed our INP-Silicatein fusion protein under the control of the pompR promoter in order to allow differential expression of outer membrane targeted silicatein based on exposure to red light.

Surface Displayed Silicatein

Our surface display team intends to use either an outer membrane protein A (ompA) from E. coli (BL21 strain) or ice nucleation protein (INP) to create a fusion chimera to display silicatein on the surface of the E. coli cell. Both ompA and INP protein can serve as a suitable carrier for other proteins which need to be localized to the exterior of the cell. The silicatein gene will be fused to the carrier protein using PCR overlap extension and other recombinant genetic methods. This fusion gene will then be expressed in living cells under stringent genetic regulation and the kinds of materials that can be nucleated will be observed.

Our initial efforts were focused on cloning ompA and generating a fusion with it and silicatein using PCR overlap extension. Our efforts to produce such a fusion protein failed, so we turned our attention to the use of INP instead.

Ice nucleation protein (INP) is an outer membrane protein originally discovered in Pseudomonas syringae. The protein has the capability of catalyzing the formation of ice crystals in supercooled water 6. INP has distinct domains: the N-terminal module is responsible for targeting and surface anchoring, while a central domain is a series of repeating units that dictates the ice nucleation activity (INA)2, 7. It has been shown the central domain has no impact on anchoring a foreign protein 9. In E. coli, fusing a heterologous protein to INP does not affect the functionality and expression of INP, and the fusion product is stable even in stationary phase 1. In addition, even when INP is expressed at a high level, it will not typically disrupt the cell membrane structure or interrupt cell growth 3. In comparison to other anchoring systems, INP has been shown to be capable of carrying proteins up to 119 kDa, whereas other display systems, such as PgsA, can only carry up to 77 kDa 9. A good carrier protein candidate should have a strong anchoring structure to secure the passenger proteins on the cell surface; it should be compatible with heterologous proteins for the process of fusion; and it should be resistant to proteolytic enzymes in its surrounding 4.

System Regulation

Our regulatory team has decided to reconstitute the light induction system or Coliroid which was the work of the 2004 joint University of Texas at Austin and UCSF iGEM team and is described at http://partsregistry.org/Coliroid 5. The Coliroid is a two component response mechanism which is composed of three genes. First, heme is used to create a phycocyanobilin by two genes isolated from Synechocystis, pcyA and ho1. This phycocyanobilin then associates with a chimeric light receptor, Cph8 which is the fusion product of Cph1 and Envz-OmpR. Stimulation with red light inhibits autophosporylation of the receptor which can be used to produce a differential output of INP-Silicatein.

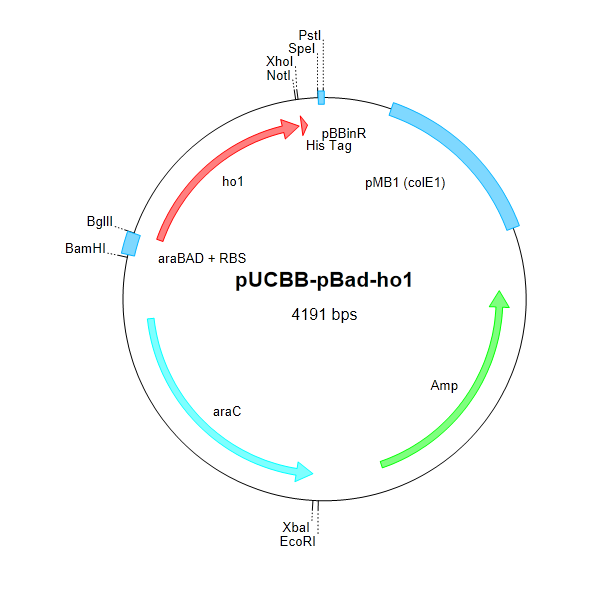

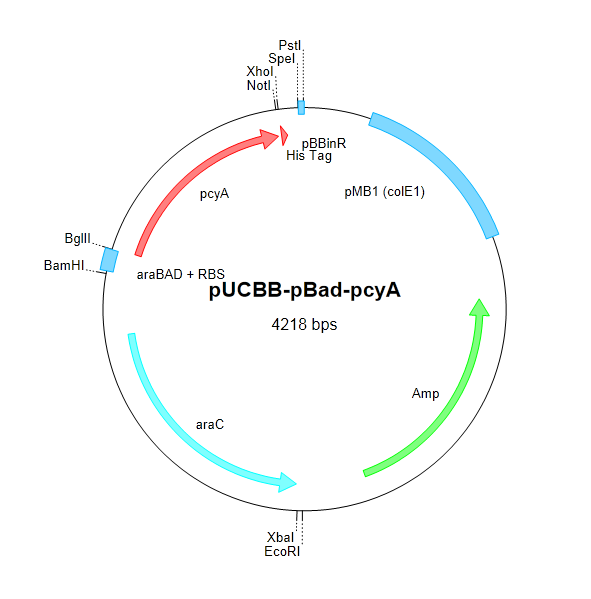

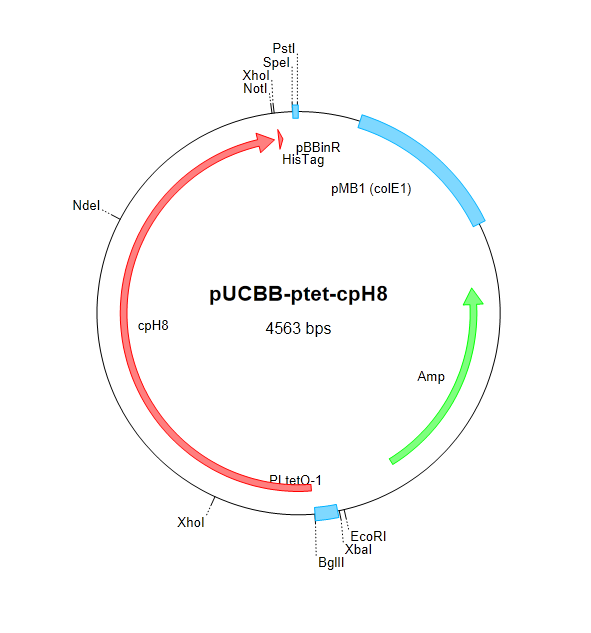

After attempting and failing to recover the Coliroid parts from the DNA distribution kits (BBa_I15008, BBa_I5009, BBa_I5010, and BBa_M30109), we began cloning pcyA and ho1 from Synechocystis. The Voigt lab was kind enough to send us the Cph8 part in a plasmid which we were able to successfully clone into our own vectors. Below is a schematic describing the construction of the complete Coliroid regulatory system.

Figure 3. We began constructing our regulatory cascade by cloning pcyA and ho1 into pUCBB-pBad and Cph8 into pUCBB-pTet as shown above.

Figure 4. pUCBB-pBad-pcyA was digested with XbaI and PstI and pUCBB-pBad-ho1 was digested with SpeI and PstI. The pcyA insert was then ligated into the ho1 backbone to yield pUCBB-pBad-ho1-pcyA.

Applications

Our proposed system has many practical uses. Bionanotemplating could be used to generate biologically inert medical devices, precision crafted parts, nanochips, and many other useful products. The advantage of our system over contemporary industrial processes is that bionanotemplating can be done at room temperature and often with mild reagents. In contrast, industrial implementations have great energy demands due to the extreme heat which is often necessary to produce these products and frequently requires the use of caustic chemicals.

Our system is designed to work primarily in two dimensions and has limited capabilities for producing complex three dimensional structures. Further enhancements might include use of IR/heat-shock induction to facilitate complex three dimensional constructs. Furthermore, this technology could be expanded to nucleate different materials to produce a broader array of products. For example, our team postulated the use of this technology to develop bio-mimetic bone materials which might allow doctors to generate biologically compatible bone grafts in the exact physical dimensions required by a patient.

References

- Jung HC, Park JH, Park SH, Lebeault JM, Pan JG. (1998) Expression of carboxymethylcellulase on the surface of Escherichia coli using Pseudomonas syringae ice nucleation protein. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 22:238-354.

- Kozloff LM, Turner MA, Arellano F. (1991) Formation of bacterial membrane ice-nucleating lipoglycoprotein complexes. J. Bacteriol 173:6528-6536.

- Kwak YD, Yoo SK, Kim EJ. (1999) Cell surface display of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 on Escherichia coli by using ice nucleation protein. American Society for Microbiology 6:499-503.

- Lee SY, Choi JH, Xu Z. (2003) Microbial cell-surface display. TRENDS in Biotechnology 21: 45-52.

- Levskaya A, Chevalier AA, Tabor JJ, Simpson ZB, Lavery LA, Levy M, Davidson EA, Scouras A, Ellington AD, Marcotte EM, Voigt CA. (2005) Synthetic biology: Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature 438: 441-442.Mararitis A, Bassi AS. (1991) Principles and biotechnological applications of bacterial ice nucleation. Crit Rev Biotechnol 11:277-295.Schmid D, Pridmore D, Capitani G, Battistutta R, Neeser JR, Jann A. (1997) Molecular organization of the ice nucleation protein InaV from Pseudomonas syringae. FEBS Lett 414:590-594.Tahir MN, Theato P, Muller WEG, Schroder HC, Borejko A, Faib S, Janshoff A, Huth J, Tremel W. (2005) Formation of layered titania zirconia catalysed by surface-bound silicatein. Chem. Commun 5533-5535.van Bloois E, Winter RT, Kolmar H, Fraaije MW. (2011) Decorating microbes: surface display of proteins on Escherichia coli. Trends in Biotechnology 29:79-86.

240px

"

"