Team:Caltech/Human Impact

From 2011.igem.org

|

Project |

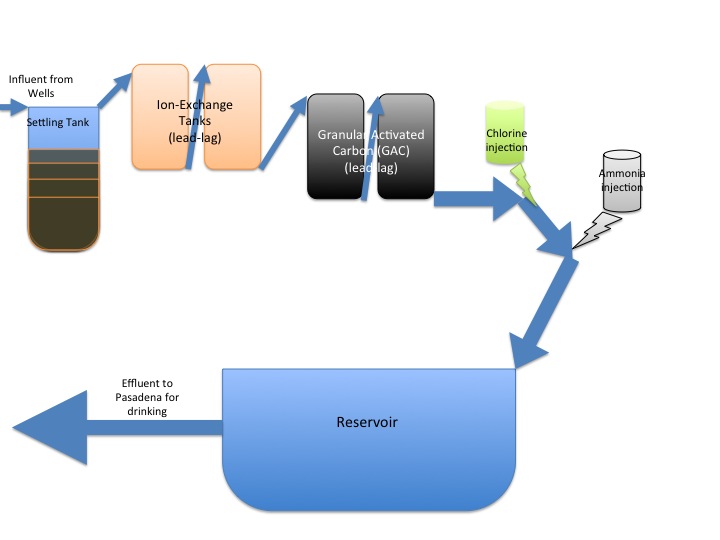

How do we treat water?Since we would like to treat water to remove endocrine disruptors, we wanted to learn more about how water is treated before and after human use. We visited 3 water treatment plants. At Monk Hill, they took contaminated groundwater and purified it for drinking in Pasadena. San Jose Creek cleaned sewage and industrial wastewater for reuse and discharge into the environment. The Edward C. Little Recycling Facility used newer technology to treat partially treated wastewater for industrial use. We hope to give an overview of the water treatment process in the Pasadena and Los Angeles area. Bacterial Treatment of Volatile Organic Compounds at JPLThe Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) is a designated [http://yosemite.epa.gov/r9/sfund/r9sfdocw.nsf/3dec8ba3252368428825742600743733/1f90d484b35ee20f88257007005e93ea!OpenDocument Superfund site] due to volatile organic compounds (VOC) and perchlorate contamination of groundwater caused by rocket fuel testing in the 1940s and 1950s. One novel treatment involves a fluidized bed bioreactor that uses the contaminated groundwater as influent. Solid carbon is provided as a surface for bacteria to grow on as water flows through the tank. Contact time is 15 minutes, and the system processes water at 300 gallons per minute. Before injecting back into the source, the water is filtered with Trimite, a gravel and carbon mixture. This process removes VOCs from the source and further dilutes the VOC levels in the groundwater. Creating Drinking Water from an Extremely Impaired SourceThe Monk Hill Treatment Plant is located just east of JPL, across the Arroyo Seco. Groundwater flows from JPL toward Monk Hill, and according to the plant, the contamination plume is spreading. However, as a Superfund Site, NASA and the EPA work on cleaning at the source of pollution, injecting clean water back into the groundwater to dilute contaminants and reduce risk of spreading. The influent at Monk Hill is still considered extremely impaired. Monk Hill has 4 wells on site between 550 and 700 feet deep that draw from the Arroyo Seco groundwater and surface water. Since they were installed beginning in 1924, part of the development of the Monk Hill plant involved rehabilitating the wells by adding a new lining and packing gravel in the space between the linings to prevent infiltration. Influent from the wells goes to a settling tank to remove most particulates before further treatment. This is a standard process and helps clean the water and protect the downstream infrastructure. There are 4 pairs of ion-exchange tanks that remove perchlorate. They are filled with beads of resin, which feel slippery to the touch. The tank is much like a large column: influent comes in at the top and gravity draws the water through the packed resin. Then the effluent from one tank is used as influent for a second ion-exchange tank, in a lead-lag configuration. Levels of perchlorate can be checked at different heights along the tank through outlet valves. When the resin reaches max perchlorate capacity, it must be replaced. During resin replacement, tanks are inspected for integrity and disinfected with sodium bicarbonate. Once resin beads are added, the tank is backwashed to remove air and stratify the beads. The water then goes through 5 pairs of granular activated carbon (GAC) tanks. These have large particles at the top and smaller ones at the bottom of the tank. Water goes through the tank from top to bottom, and the GAC removes VOCs.

Treated water then is injected with chlorine gas from 150 lb. cylinders to disinfect it. Up to 250 lbs. can be injected per day, so at peak operation, tanks have to be replaced every 4 to 5 days. Ammonia is added afterwards to create chloramines, as the level of free chlorine gas is strictly regulated for health reasons. The facility has alarms that close the area and alert the fire department at 1 ppm and 3 ppm. Treated water from all active wells is mixed in the covered Windsor Reservoir, which can hold 4.8 million gallons. This water is then used as drinking water in the city of Pasadena and is cheaper than imported MWD water. Cleaning Waste at San Jose Creek Wastewater Treatment PlantPart of the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County, the San Jose plant treats sewage and industrial wastewater to up to a tertiary level treatment that can be used as recycled water for irrigation, for industrial use, or injected back into the groundwater. Industrial wastewater must undergo pretreatment at the source if certain chemicals and processes are used. Influent passes through screens to prevent large solids from ending up in the tanks and clogging the pipes. The plant has seen some strange things that are washed into the plant, including a horse. Primary treatment involves the addition of ferric chloride to coagulate hydrophobic solids, which are sent to the Joint Water Pollution Control Plant (JWPCP) in Carson, where they can be anaerobically digested to create methane for powering the plant. They treat this waste to secondary level, but due to the high concentration of salts, it cannot be reclaimed and is discharged to the ocean. The smell is not even as bad as aseptic tank, as the water and solids do not remain in the plant long and there are metal covers over each settling tank. The air from the tank is processed to use in the aerobic secondary treatment microbiological tanks. Secondary treatment involves nitrification and denitrification of the water through microbiological treatment. San Jose Creek uses activated sludge with three zones: aerobic, anoxic, and anaerobic, although some air is added to anaerobic to keep turbidity high enough so that the microbes can access nutrients. Small solids can disturb the turbidity: the little beads in hand sanitizer once caused a problem. Each wastewater treatment plant has its own unique microbiological ecology due to selection pressures from influent sewage. Outside bacteria, protists and fungi can upset the local ecology, potentially creating a septic situation where the waste is not treated. Yeast from a bakery once killed many of the microbes due to its high oxygen demand. However, if a plant’s microbes are wiped out, it can be reseeded using another plant’s microbes. Eventually, the microbial population will return to the same diversity as before. In the event of a plant shutdown, the sewage can be sent downstream to JWPCP and other plants for treatment. After going through the microbial tanks, the water is held in a settling tank to remove and recover the activated sludge. Some of the activated sludge is sent to JWPCP as waste and the rest is returned to the microbial tanks. Tertiary treatment begins by gravity filtering the water through sand and gravel. The filter has to be changed once per year. If the plant wanted to remove ammonia, they could have a zeolite filter, but San Jose Creek uses a nitrification-denitrification process so the z Ammonia and then chlorine are injected for disinfection. Sulfur dioxide is added and then the water is ready for reuse as irrigation. Chlorine is removed before discharge into the environment. The recycled water is not approved for drinking because there could be something that cannot be measured or is not measured because it is not known to be a hazard. San Jose Creek processes 100 million gallons of water per day. Water goes through the plant in 8 to 10 hours. Recycled water is sold at 1/3 the price of well water. Methane captured by the nearby landfill also run by the Sanitation District is used to power the plant. Reclaiming Wastewater at the Edward C. Little Recycling Facility in the West Basin Municipal Water District“We need to figure out how to get the public to buy it,” says Ed Little, Director of the West Basin plant. Public perception of the “dirtiness” of water is a major obstacle preventing reclaimed wastewater from being used for drinking water. Laws currently prohibit reclaimed wastewater from being directly sold as drinking water. Instead, the water must be discharged into nature, and those that pump from nature will treat it and sell it as drinking water. The plant’s influent is secondary treated wastewater from Hyperion Water Treatment Plant that would normally be discharged into the ocean. The water is split into two types of tertiary treatment: settling tanks with chlorine injected, and microfiltration with UV disinfection. The 25 feet-deep settling tanks are injected with ferric chloride to coagulate solids, giving the tanks a red coloring. Then the water is chlorinated and dechlorinated, as West Basin sells this quality of water for irrigation, processing 10 million gallons per day. Compared to the newer method of microfiltration, standard tertiary treatment takes more space and chemicals. The microfilters are made of polypropylene and have 0.2 µm pores. Water is forced through the filter in cycles of 20 minutes of filtration, 1.5 minutes of backwash to clean the filter. Fibers are packed in a cylindrical column and the facility can identify individual fibers that fail. These membranes require frequent cleaning with citric acid, an unnamed caustic and a surfactant soak. To increase the time between cleanings, the facility is testing ozone injection before filtration, which breaks organics into smaller molecules. Microfiltered water is then treated by reverse osmosis (RO). RO membranes used to be made of cellulose acetate, but now are made of polyamic membrane, which can withstand higher pressures and has better rejection of contaminants, but is not resistant to chlorine. The membrane flux is 12 gallons per square foot per day, with water being pushed through using 160 lbs. of pressure. 85% of the water is recovered. The rest is lost in brine, the concentrated salts and chemicals discharged into the ocean as waste. Depending on the quality needed by the customer, the water may be treated twice with reverse osmosis. Then the water is sterilized using UV. Hydrogen peroxide is added to remove organic radicals generated by the UV treatment. Lime is added to raise the pH.

|

"

"