Team:Glasgow/Biofilm/P. aeruginosa

From 2011.igem.org

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen of a wide range of animals that includes humans. Normally it lives in soil and water however it can be found in skin flora and artificial environments like the surface of a catheter. It is a rod shaped gram-negative bacteria that has unipolar flagellae for motility. Although it is aerobic but can survive in hypoxic conditions. As an opportunistic pathogen it can cause nosocomial most commonly in the elder or immunocompromised. Most commonly this can lead to infections of the kidneys, lung or urinary tracts which are had to treat with conventional antibiotics as it forms biofilms. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an excellent model for there is a large amount of research about it especially as it is medically significant. It can form thick biofilm in less than 24hrs even at room temperature. |

|

P.aeruginosa Biofilms

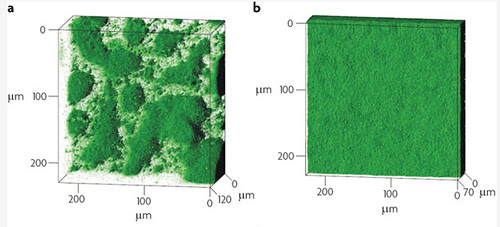

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the standard organism for the investigation of biofilms, as it is very adept at forming them. This ability is mainly due to the production of exopolysaccharides (EPS), most notably the protein alginate, that is produced by the mucoid strains of P. aeruginosa and leads to the production of notably thicker and more stable biofilms,though it is not essential for biofilm formation

The strain that was chosen for this project is the wild type PA01 strain, that forms stable smooth, and more homogenous biofilms.

Figure1: Biofilm architecture in muciod and non-mucoid P.aeruginosa strains. a) Typical biofilm architecture of the mucoid (alginate over-expressing) SG81 strain b)The smoother biofilm architecture typical of non-mucoid strains such as the wild type PA01 that was used in this project

It has long been postulated that P.aeruginosa has significant resistance to a wide range of antibiotics because of it's ability to form sturdy, resistant biofilms. Drenkard & Ausube showed that biofilm formation is strongly correlated to antibiotic resistance, allowing P.aeruginosa to thrive in almost any environment.

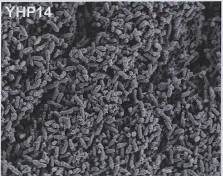

Image 1: 1000x EM of P. aeruginosa biofilm, showing its densely packed structure (courtesy of Dan Walker, University of Glasgow) |

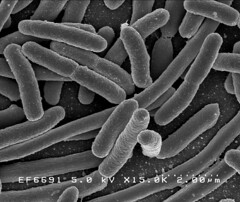

Image 2: 15,000x EM of E.coli for comparison. No fimbriae or EPS is visible. (courtesy of Rocky Mountain Laboratories) |

Properties of P. Aeruginosa Biofilms

|

Method

As we were trying to specifically disperse areas of biofilm it was necessary to establish a base rate of dispersal of the biofilm without using any of the dispersal mechanisms we designed. This would allow us to show quantitatively the increase in rate of dispersal that our different dispersal biobrick could generate when compared to a biofilm of non-transformed bacteria. This assay is assuming that you are measuring the base rate of dispersal after transferring the biofilm into fresh media. This assay was developed with the prospect of using it to measure an induced increase in dispersal. To measure the base rate of dispersal glass slides were put into 50ml tubes containing 20ml of LB broth. The LB covered around a third of the glass slide, this is the area where the biofilm would form. The LB was then inoculated with 20μl of overnight culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These tubes were then left on a bench top shaker at room temperature for a set amount of time (time points ranged from 1hr to 48hrs). After the biofilm had grown its allotted time the glass slide was carefully removed and placed into a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB (which completely covered the biofilm) and left to allow the bacteria to disperse for 1hr. The slide was then transferred to a fresh 50ml tube with 25ml of LB. The biofilm is scraped off the slide using a thin flexible spatula. At this point both the dispersed cell and the biofilm scrapings were sonicated to stop clumping and plated in serial dilutions. |

Figure 1: Number of viable cells in biofilm compared to number of cells dispersed from the biofilm in one hour. The base rate of dispersal remains roughly proportional to the number of cells in the biofilm. The information for the time point hour 14 for the biofilm was not available. |

To make the images of biofilm formation, biofilms were formed on glass slides inserted into 50ml tubes. The tube was filled with 20ml of LB broth and inoculated with 20μl of over night culture of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. The biofilms were left to form for the time indicated on the images.

Results The number of cells that dispersed from the biofilm seemed to be proportional to the number of cells in the biofilm with a ratio of roughly 5 dispersed:1 in biofilm. Figure 1 shows the number of dispersed cells when compared to the number of cells in the biofilm in both a graph and a table. Figure 2: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth over time. These photographs were taken after 1hr, 14hrs and 48hrs of biofilm growth. They were stained using a Grams stain method that is designed specifically to avoid sheer forces being applied to the delicate biofilm structure. Details of this method are included in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms lab book.

Figure 2: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth over time. These photographs were taken after 1hr, 14hrs and 48hrs of biofilm growth. They were stained using a Grams stain method that is designed specifically to avoid sheer forces being applied to the delicate biofilm structure. Details of this method are included in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms lab book.

P. aeruginosa in DISColi

Although P. aeruginosa forms biofilms admirably and quickly under a range of conditions, we decided against using it as a chassis in the DISColi project.

The disadvantages of working with P. aeruginosa are:

-It is difficult to transform, and would require a shuttle vector we had no access to

-It is not suitable for transformation with most standard biobricks, which are intended for primary use in E. coli

-It is naturally resistant to many antibiotics, making selection for transformants practically impossible

New Chassis

The decision not to use P. aeruginosa brought with it the obstacle of finding a new chassis that would form biofilm, but without any of the disadvantages of P. aeruginosa. Preferably a strain of E. coli...

We got lucky with E. coli Nissle 1917 : Our new biofilm chassis!

Continue to E. coli Nissle 1917

Go back to Biofilms

References

Flemming, H. & Wingende J., 2010. The Biofilm Matrix. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8, 623-633

Drenkard,E. & Frederick M. Ausube

"

"