Team:Calgary/Project/Chassis/Pseudomonas

From 2011.igem.org

A Chassis Using Native Tailings Pond Species

A Pseudomonas Conjugation System

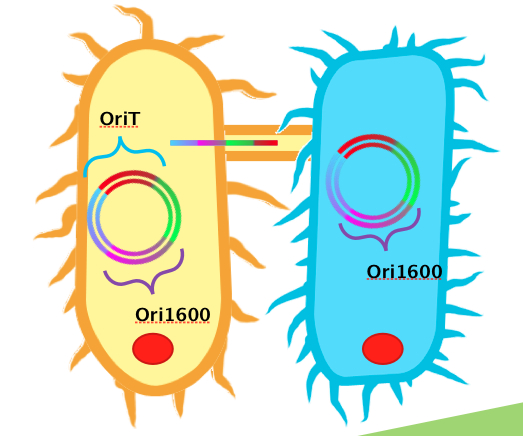

In order to use Pseudomonas as an effective platform for sensing naphthenic acids, our team recognized that we would need it to take up our biosensor plasmid construct with high efficiency. To do this, we decided to design a conjugation system, capable of conjugating plasmids from E. coli to Pseudomonas. In order for conjugation to occur, the necessary plasmid DNA must already be inserted into E. coli. A unique sequence recognizable by relaxase and nickase called oriT (origin of transfer), must be coded into the plasmid. Additionally, the plasmid requires replication origins for both E. coli (such as ColE1) and Pseudomonas spp. (such as ori1600). Ori1600, which we used in our system, is a replication-stabilizing element for Pseudomonas spp., and requires ColE1 to function. All other enzymes required for conjugation are available in the receptor Pseudomonas species.

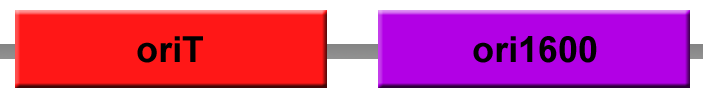

We obtained DNA for both oriT and ori1600, BioBricked them and have submitted them as BioBrick parts. Using BioBrick cloning, we put these two elements together on a single plasmid to make a testing construct. Already present in the registry is an oriT part J01003, which was characterized by Heidelberg in 2008. This part was used for conjugation between strains of E. coli. Theoretically, this part could also be used for conjugation between Pseudomonas and E. coli. Based on the sequences however, we hypothesized that our oriT, which is considerably longer, may have additional regions to improve efficiency in conjugating to Pseudomonas. To test this, we built additional constructs using J01003 and our ori1600 part to compare to our oriT- ori1600 construct.

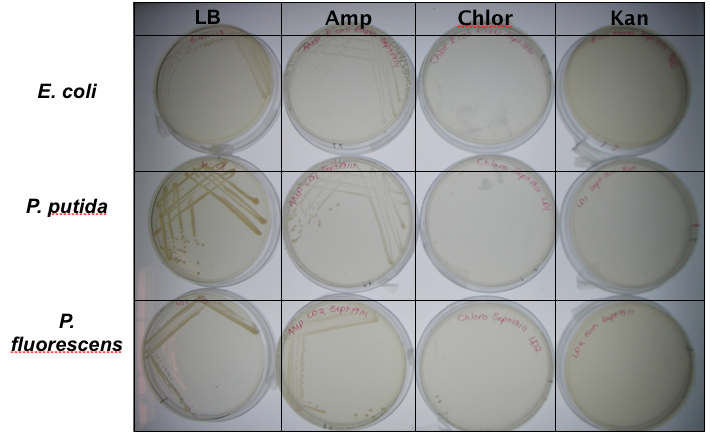

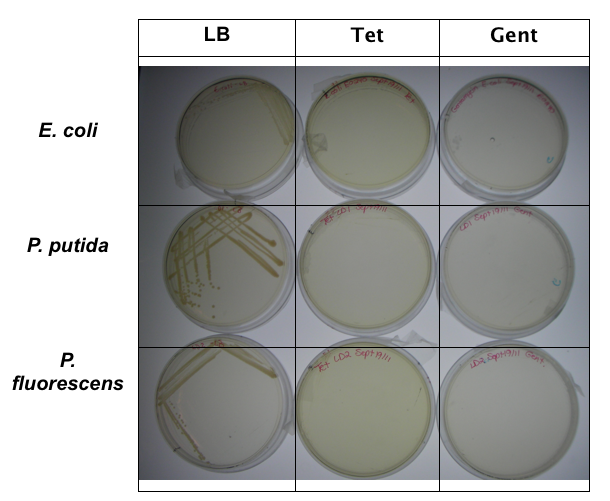

In order to test that our constructs were working, we needed a selective marker. We performed a growth assay on our Pseudomonas strains, verifying if they can grow on different antibiotics. Pseudomonas was streaked on LB agar plates containing no antibiotics, tetracycline (25 mg/ml), chloramphenicol (35 mg/mL), kanamycin (50 mg/mL), ampicillin (100 mg/mL) and gentamyacin (50 mg/mL) (figure x). Growth was observed on LB alone as well as on ampicillin, indicating that Pseudomonas, as expected, is naturally resistant to ampicillin. The lack of growth on the other antibiotics, however, indicated that resistance markers for these could possibly be used to test out the functionality of our constructs.

Based on this, we moved our constructs into tetracycline and kanamycin resistance vectors for testing. Colonies of E.Coli containing our plasmids were used to innocluate 5 mL LB cultures with kanamycin-50 and tetracycline-25. 100 μL of our two Pseudomonas strains were added and cultures were shaken in a 26°C incubator. OD readings of cultures were taken to standardize cell counts and cultures were then plated on MacConkey agar plates. MacConkey agar, which is a reddish-purple color, is able to distinguish between bacteria that can and cannot metabolize lactose via a color change. Bacteria that do not metabolize lactose, such as Pseudomonas, use peptone instead and reduce ammonia, which causes a yellow color change of the plates due to an increase in pH. E. coli, on the other hand, do metabolize lactose, and therefore no color change is seen.

"

"