Team:Freiburg/Modelling

From 2011.igem.org

Contents |

Modelling: Rational protein design

The Idea

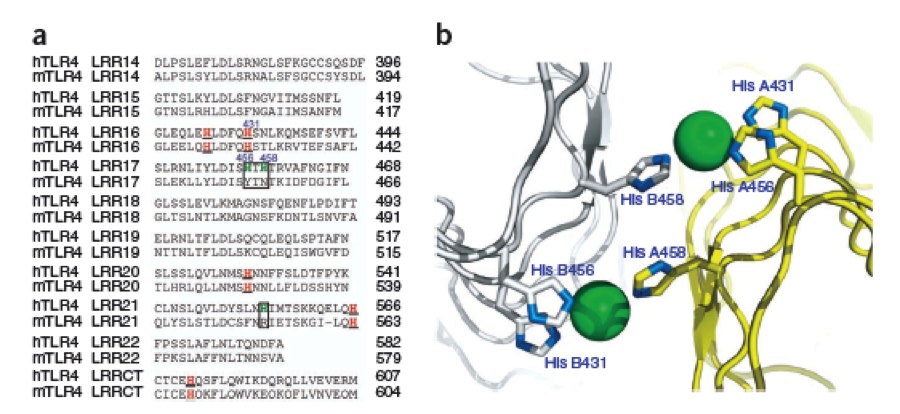

First there was the idea to replace the chemically produced Ni-NTA columns by some biological, reproducible material. It seemed unreasonable to produce an ion precipitating substance in a complicated, energy consuming way – completely artificial, while so many proteins in nature are capable of the same task – and much more complicated things. But how to harness that? The second milestone in the generation of the idea came up in a lecture of Prof. Martin, about Nickel allergy. He found a mutation in the TLR-4 receptor that introduces Histidines in the LRR motif of the protein, which are capable of binding nickel and thus forming complexes of receptors on the cell surface of immune cells, triggering the inflammatory reaction.

The core structure

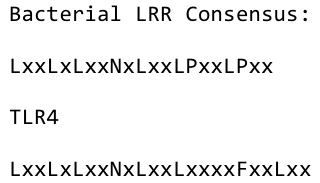

This was the necessary clue that gave answer to the question. In the following work, a lot of investigation about the perfect Nickel precipitating protein was done. It seemed that there is no optimal natural protein which would serves our needs. Furthermore, many of the natural LRR proteins – of course – have their own biological function, we we were afraid could interfere in the cellular system we wanted to express them in. Luckily there are over a thousand already known structures of LRR proteins, what gave us a broad choice of motifs to choose and compare. The Construction of a new protein After a long and detailed search, we found out that it is most reasonable to use bacterial LRR motifs, since they seemed very well conserved in sequence, and they are the shortest – with only 21 amino acids per LRR repeat. (Wei 2008, Kajava 1998). We wanted to have a protein as simple and as predictable in behavior and structure as possible. Several search inquiries led to the most conserved and shortest of all bacterial LRR (PDB: NO)EDIT!, unluckily this protein is a toxin derived from Yersinia pestis. We of course did not want to mess around with toxins,

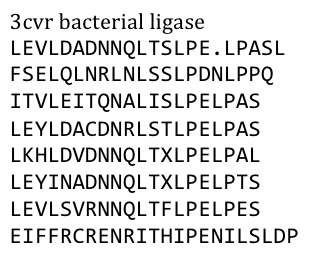

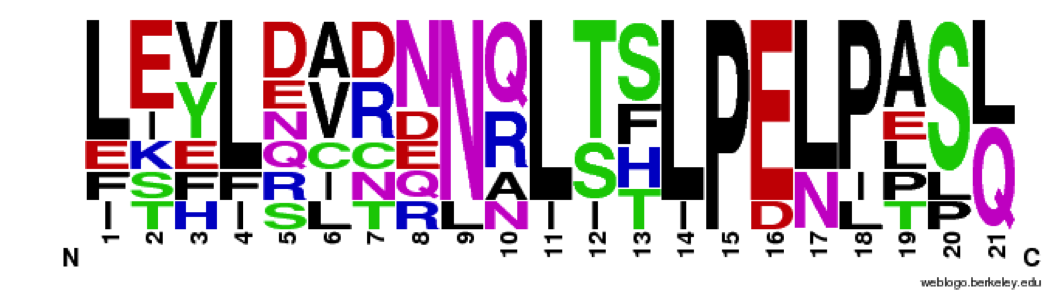

The aminoacid sequence of a bacterial ligase we chose for our design (PDB:3CVR) |

especially not with one of the black plague. We also did not know what amino acid pattern on the LRR motif would cause the toxic effect. Probably, there would have been no harm in using this protein alone, even if we did clone and express it, but why should we do that when we have a huge choice freely available anyway. Finally, we settled on the bacterial ligase PDB:3CVR. A ligase would be definitively harmless, especially since we planned to restructure it entirely.

To do this we needed to understand how the structure of the Ligase was made up. Our desired protein LRR motif was only a part of a bigger protein “factory” which included several domains that seemed to serve distinct functions – more than we had use for. So we exclusively used the LRR domain. It seemed to us that this domain had mostly a structural role in this “factory”, but we could still not exactly tell. To avoid any unspecific biological function it was necessary to rearrange the amino acid composition. We fed the protein sequence in a free online consensus sequence generator called weblogo from the Berkeley University.

Consensus sequences derived from the repeating loops of the 3CVR ligase to work out the conserved aminoacids and shared chemical properties of the different positions in the loops. |

By analyzing the logo it was obvious which positions of the LRR motif were conserved and which not – AND: which of the non-conserved amino acids appeared in what kind of pattern. Were there positions in the protein that required a polar amino acid? Or a non-polar, hydrophobic /-philic, charged, non-charged one?. We compared the consensus sequence with the 3D structure, using PYMOL, to extract as much information as possible, and then came up with this ideal consensus sequence:

ideal consensus sequence extracted from the consensus motif above |

imposing desired functions

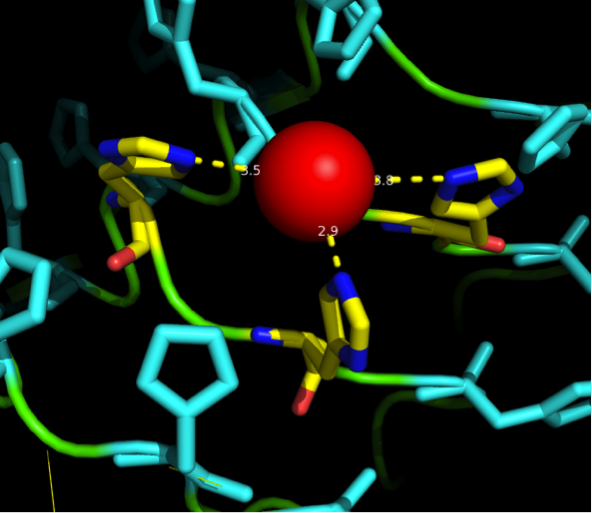

The next consideration we had to do was: how many Nickel do we need on the surface of our ideal Nickel binding protein, in what pattern, with what distances between, and at which angles toward each other to allow proper ion complexion? Nickel can be complexed by imidazole structures from 4 planar orthogonal directions, as well as to axial positions. It can, however, only take four ligands at once - preferably in a planar orientation. Cobalt has a bipyramidal setup for ligand-binding, too, but can take up to six ligands. The distances from an N-atom in the Imidazole ring to the ion had to be between 3 and 6 Angström. We found a crystal structure of a different protein (PDB:)EDIT which was resolved with three Histidines complexing a Nickel ion for a comparison, as well as some old publications that analyzed peptide ion bonds that taught us how the complex should look like. (Jordan 1974) We wanted our protein to be short. First in order to cause as little unspecific binding as possible and further to allow an easy expression as well as for keeping costs low for gene synthesis. For a proper purification of His-tagged proteins in Ni-NTA columns we knew that there are up to three Nickel involved in the interaction between the His tag (which consists of 6 or 7 Histidines) and the column. These have to be in close proximity to one another. There are always two Histidines of the tag binding to one ion.

This was what we had to implement into our LRR backbone.

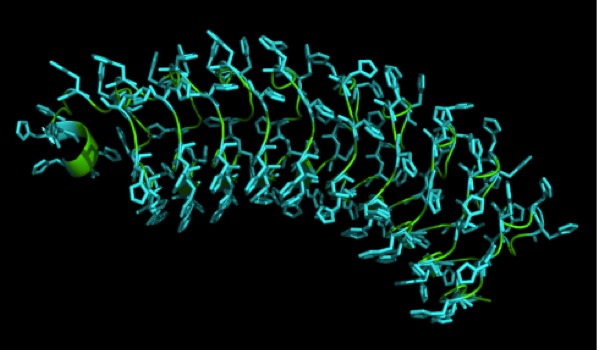

To get a first impression how Histidines are positioned in a bacterial Ligase, we replaced all non conserved amino acids by Histidines and sent the sequence for a 3D sequence prediction to I-TASSER, an online structure prediction software tool.

Caption |

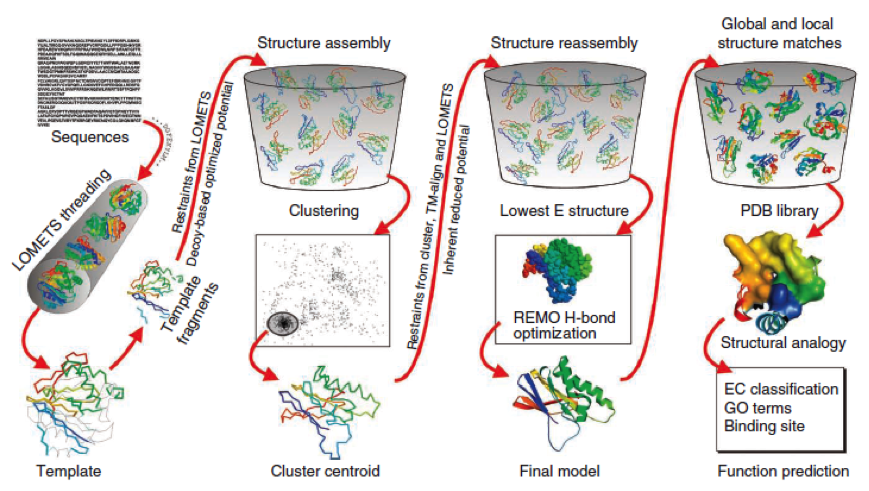

| I-Tasser: Structure prediction | |

The community-wide Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) ranked the I-Tasser as the best protein prediction method in the server section. The method of the I-Tasser can be divided into 4 stages: Stage 1 is called threading. In this stage the sequence or parts of the sequence or motifs are compared with already known protein structures to identify evolutionary relatives and predict secondary structures. This gives a sequence profile and together with the query sequence it is threaded by LOMETS, a server combining seven threading programs which evaluate the sequence respectively the templates with an individual score EDIT (?). The top templates are selected for further consideration. Stage 2 is responsible for structural assembly. The structure is modeled ab initio by aligning different templates from the threading. This is a very complex process and different programs are involved. Stage 3 is a model selection of the achievements of stage 2 with a following refinement of the predicted models. Stage 4 announces the function of the predicted molecule by its structural conformation comparing with already known proteins of PDB database. The predicted models are all evaluated by the C-Score, which assesses the quality of the prediction. It has a value from -5 to 2; the more positive the C-Score the merrier EDIT and more plausible the predicted structure is. 1.Ambrish Roy, Alper Kucukural, Yang Zhang. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nature Protocols, vol 5, 725-738 (2010). 2.Yang Zhang. Template-based modeling and free modeling by I-TASSER in CASP7. Proteins, vol 69 (Suppl 8), 108-117 (2007). | |

Caption |

We received this pdb file with a C-score of 0.53. Obviously this was not a realistic model, since the folding would obviously be impaired by so many Histidines everywhere. But is was useful for finding several good locations where the Nickel could fit in in respect to the requirements it has for binding ligands. We manually fit in a Nickel ion, as it was crystallized in the mentioned PDB file, and measured the distances and evaluated the 3dimensional orientation of the Histidines towards the Nickel. Histidines can coordinate ligands with their free electron pair pointing planar away from the imidazole ring. What we further realized from the structure file was, that the ends of the LRR segments were “open”, meaning the hydrophobic core of the protein was exposed and as it is visible in the prediction, curled in on one end into a sort of helix. This means the protein folding is not reliable and the structure needs some sor of cap on either end in order to stabilize the LRR core motif.

Caption |

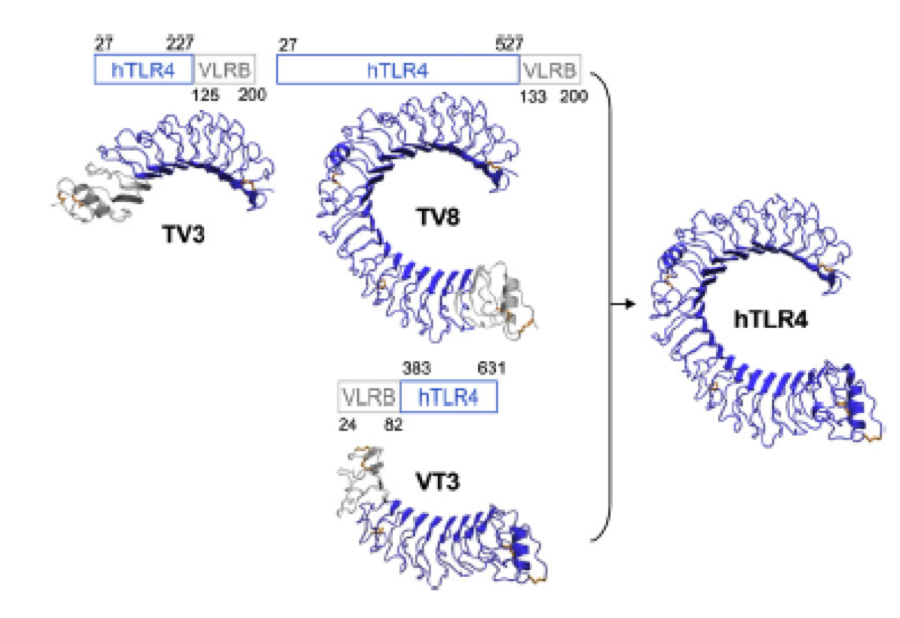

A solution to this was shown by Schmidt et. al. 2010, who crystallized the TLR-4 receptor.

In this very useful work he dissected the TLR4(PDB: 3FXI) EDIT into 3 parts, since it was too large and unhandy to be crystallized at once..

stabilizing the structure

Caption |

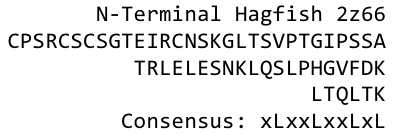

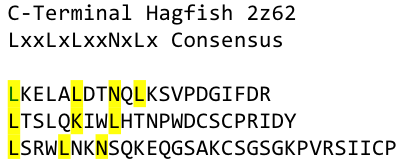

To overcome this problem of an exposed hydrophobic core, he used the N- and C-terminal protein fragments of a LRR protein derived from hagfish. They tried a variety of different versions of how to glue together his fragments and these N- and C-terminal caps until they found a working one.

We used this knowledge for our purpose, applied the same sequences and attached them to our protein sequence. These caps do still in parts show the typical LRR consensus sequences (which luckily is highly conserved in all kingdoms of life!), which made it possible to fit them onto our stack of LRR loops in the right position.

To the outer end the protein has a helix on the N-terminal side, shielding off the core and the C-terminus while the LRR disappears slowly turn by turn with more and more hydrophilic amino acids replacing the LRR consensus sequence.

|

Caption |

Caption |

Caption |

optimzing the sequence

After combining these caps with our structural analysis for possible Nickel binding sites and filling the empty positions of the consensus sequence with the ideal sequence derived from the ligase sequence (see above), we were still unsure whether this would work out. To increase our chances of success we designed six different versions with distinct Histidine patterns on the LRR core.

|

Caption |

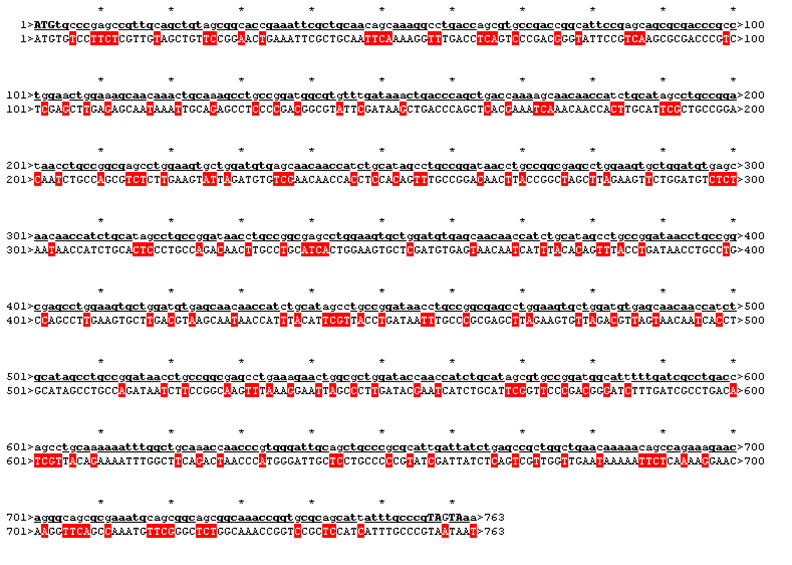

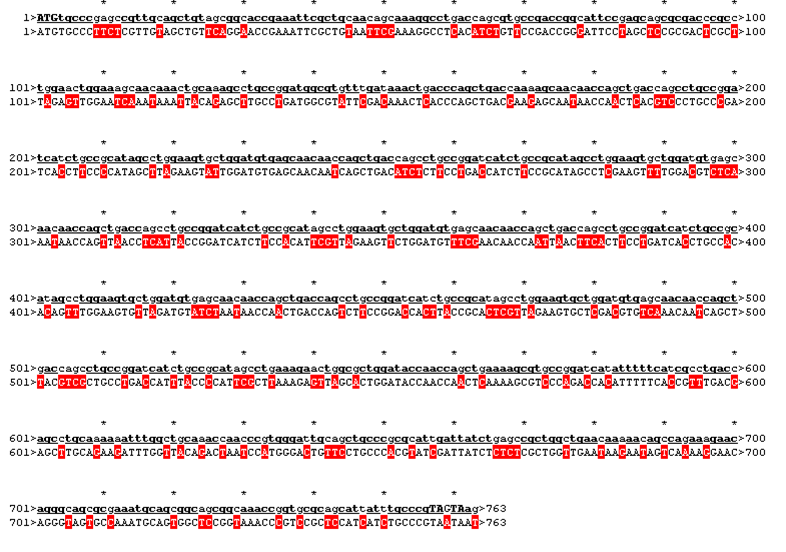

After evaluating the C-Scores of I-TASSER we saw that our favorite versions 1,2 and 4 gave acceptable scores. We then reverse translated them with a codon usage optimized for E. coli, using http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/rev_trans.html The sequence was handed over to our sponsor ATG:biosynthetics, who ran their own analysis on it, to optimize the sequence for RNA trafficking and secondary structures. In pictures below the alignment of our reverse translated sequence and the returned sequence is shown: ours above, ATG:biosynthetics sequence below. Underlined in red are the mutations the company introduced to optimize the expression. They also were so kind as to synthesize the three genes for us as a gift.

A mathematical model to determine the experimental design

The modeling was done in order to realize what parameters are crucial and which experiments need to be conducted to determine those.

We asked the following questions:

How much Precipitator protein will bind to the Plastic surface? How stable is the binding of the plastic binding tag to polystyrene depending on the size of the column? How much His-tagged protein will the Precipitator be able to bind? Which parameters do we have to determine? How often can one column be reused until the efficiency goes too low due to unbinding of the Precipitator protein from the plastic surface? How can we find out the affinity constants? We developed a Flow-chart diagram to make the reactions that happen before, during and after the washing steps visible. Subsequently we developed chemical reaction equations and formulate differential equations after them. Here appeared the parameters we had to determine. After carefully considering these equations, we introduce several simplifications, either because the expected information was marginal, or because the information was experimentally not accessible.

Conclusions

To determine the Affinity k_D, experiments to find out the binding affinity of the plastic binding domain are necessary. To get a direct access to these values, we cloned the plastic binding domain in front of a GFP. Then, dilution and washing assays could be performed on polystyrene microtiter plates, red out by a fluorescence plate reader. The desired parameters could be calculated by measuring dilution rows of GFP proteins and measuring the fluorescence signals at the different concentrations. C_total could be determined by a dilution row with subsequent washing steps, to find out at what [P] concentration there is a saturation. See description of the plastic binding subproject for more detailed explanation on the experimental setup.

A qualitative experiment to prove that Nickel is binding the Precipitator is sufficient, since k_2 >> 1 and does not play a significant role in our setup. This experiment could have been done using a nanofilter that blocks protein but let through ions. The Nickel concentration of the flow through can then be measured.

Alternatively purification of the Precipitator by fusing it with a GST-tag could be done, to subsequently measure the absorbance of the protein, before and after adding Nickel to the solution. After Jordan 1974 a detectable change in the absorbance should be detectable after the complex is formed. A similar effect – a colorshift from white to blue - is visible when one prepares a Ni-NTA column. For this purpose we cloned the GST domain in front of the Precipitator. However towards the end of the project there was no more time to perfom these experiments.

References

Tiandi Wei et.al.; "LRRML: a conformational database and an XML description of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs)"; BMC Structural Biology 2008 doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-47

Schmidt, Marc et.al.; "Crucial role for human Toll-like receptor 4 in the development of contact allergy to nickel";

Nature 2010

Letter, J.E. et.al.; "Complexing of Nickel( 11) by Cysteine, Tyrosine,

and Related Ligands and Evidence for Zwitterion Reactivity";

Contribution from the Department of Chemistry, University of Alberta,

Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2G2, Canada.

Kajava, A.V.;"Structural Diversity of Leucine-rich Repeat Proteins"

J. Mol. Biol. (1998) 277, 519±527

Kim, Ho Min et. al.; "Crystal Structure of the TLR4-MD-2 Complex with Bound Endotoxin Antagonist Eritoran"

DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.002

Nieba, L. et al BIACORE analysis of histidine-tagged proteins using a chelating NTA sensor chip. Analytical Biochemistry 252: 217-228; (1997).

"

"

Contact

Contact