Complete Project Description

1. Introduction

The aim of this project is to design and implement a system exhibiting sustained oscillatory protein expression which is synchronized across a population of spatially constrained E. coli cells. The principles that govern this type of behaviour have been studied both in theory and in practice, and as such there exists a solid foundation to apply these ideas in the context of the iGEM competition. In essence, this project consists of constructing a plasmid which contains genes encoding proteins which reciprocally affect each other’s expression in a reliable manner, and experimentally measuring the expression dynamics to test the predictive value of a mathematical model. Due to the specificity of the required system parameters, and resulting difficulty in experimentally verifying the phenomena we wished to observe, special considerations regarding the experimental set-up had to be made. We hope that this system might be employed as a pace-making device to drive more complex genetic circuits requiring time-dependent gene expression, or as a component in sophisticated metabolic engineering applications.

Fig.1. Artistic rendering of the Synchronized Oscillatory System.

2. Mechanism

There are a number of genetic circuit topologies that have the potential to exhibit oscillatory behaviour under the right conditions. However, the requirement that the oscillations be synchronized posed a constraint on the components that could be used. The starting point for our genetic circuitry was a design recently published in the article “A synchronized quorum of genetic clocks” by Danino et al. This design combines elements of the Vibrio fischeri quorum sensing system with a quorum quenching enzyme from Bacillus subtilis, resulting in coupled positive and negative feedback loops which regulate the expression of a reporter protein.

Fig.2. Genetic circuit of a synchronized oscillator (Danino et al. 2010)

Basic Components:

LuxR is a transcriptional regulator in the bioluminescent quorum-sensing system of the symbiotic deep sea bacterium Vibrio fischeri. It is induced by binding the autoinducer molecule N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-homoserine lactone (AHL). The AHL-LuxR complex controls expression of the lux regulon, which contains diverging pRight and pLeft promoter elements. The pRight element has low basal transcription, and is activated by AHL-LuxR; pLeft has higher basal expression, and is repressed by the AHL-LuxR complex. This dual activity makes LuxR a useful element for controlling interconnected genetic feedback loops. The unrestricted diffusion of AHL through the plasma membrane allows spatially proximate populations of cells to experience identical AHL conditions and synchronize AHL-dependent gene expression.

The enzyme LuxI is an acyl-homoserine-lactone synthase which produces the intercellular signalling molecule N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-homoserine lactone. Placing LuxI under control of the pRight promoter results in a positive feedback loop: when increases in cell density cause the intracellular AHL concentration to rise above the activation threshold of the pRight promoter, the transcription rate of the LuxI gene is increased which in turn results in the production of more AHL.

AiiA is an enzyme from B. subtilis which degrades AHL. Its biological function is to interfere with the quorum sensing signals of other bacteria. Placing it under control of the pRight promoter results in negative feedback as a response to increasing AHL concentrations. The reporter molecule Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)is also regulated by the pRight promoter and provides a quantitative (albeit delayed) indication of the AHL concentration the cell is exposed to at a given point in time. LuxI, AiiA and GFP are all tagged for rapid degradation. Due to differences in the synthesis and degradation rates of LuxI and AiiA, there exists a space of conditions within which periodic oscillations in AHL concentration, and concomitant oscillatory protein expression can emerge. Under most conditions, the level of AHL within a population of cells will quickly reach a steady state. However, by simulating the system using a quantitative biochemical model, it is possible to predict conditions under which oscillations are likely to occur. See Modeling page for details [hyperlink]

Designs

“Hasty” system:

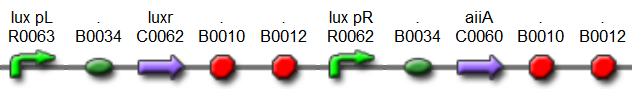

Fig.4. Synchronized Oscillator plasmids using natural quorum sensing system (Danino et al. 2010)

The first design we implemented was a BioBrick part based reconstruction of the plasmids used by Danino & Hasty. We intended to make as accurate a replica as possible in order to confirm the previously published results, and to test the viability of our experimental platform [hyperlink to Device Design]. However, there are a few differences in between the original Hasty system and our replica. While the Hasty system employs the natural lux promoter which contains divergent pLeft and pRight elements (Fig 4), the BioBrick parts we employed have both elements in the same orientation. Both the original and our system contain 3 copies of the luxR gene under control of the pLeft element. Furthermore, a different (high copy) backbone was used during the functional validation of the parts, as opposed to the low copy backbone employed by Hasty.

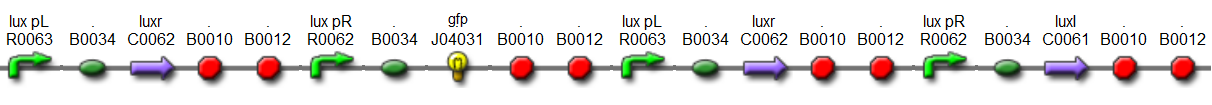

Fig.5. BioBrick part K546005 forms the positive feedback loop component of the basic synchonized oscillator.

Fig.5. BioBrick part K546005 forms the positive feedback loop component of the basic synchonized oscillator.

Fig.6. BioBrick part K546001 forms the negative feedback loop component and complements K546005.

Streamlined Design

The first modification involves simply replacing the three copies of pLeft-LuxR with a single copy of LuxR behind a constitutive promoter (ptetR, Figure 5). This will significantly reduce the size of the construct (and the complexity of the system) while exhibiting similar behaviour. In addition to this modification, the pRight promoter regulating the expression of LuxI will be replaced by a pRight/lacI hybrid promoter. This should allow the oscillation circuit to remain inactivated until it is induced by adding a pulse of IPTG to the medium. The gene LuxR is under the control of the constituve ptet promoter and should give a steady transcription of the LuXR gene.

Fig.5. Circuit view of the streamlined design with ptetR regulating LuxR, and pRight/LacI (not indicated in circuit) controlling LuxI.

Fig.6. Streamlined design with ptetR regulating LuxR, and pRight/LacI controlling LuxI. All of the parts shown in the plasmid schematically have been located and verified in the Parts Registry.

Differential Feedback Design

The second major modification is the replacement of the inducible promoter pRight controlling expression of LuxI with the repressible pLeft. This will turn the LuxI-AHL positive feedback loop into a negative feedback loop, thus changing the dynamics of the system. Induction will be controlled using the pRight/lacI promoter regulating the AiiA gene. This is an experimental design, and will have to be validated with modelling work.

Fig.7. Genetic circuit of the experimental differential feedback loop.

Fig.8. Plasmid diagram of the experimental differential feedback loop.

Advanced application: luciferin regeneration

If the project advances and the reference design can be constructed and verified without significant delays, it may be possible to implement an advanced application involving luciferin regeneration. This design would involve the replacement of GFP with the Luciferase gene, and the addition of constitutively expressed Luciferin Regenerating Enzyme (LRE), which can regenerate the substrate required for the light-emitting reaction. Though the kinetics need to be considered, this design could theoretically produce regular pulses of visible light as long as cells are provided with sufficient D-cysteine.

Fig.9. A circuit for partially self-contained luciferin regeneration coupled to periodic luciferase expression.

4. Assembly

Plasmids

The plasmids will be constructed in accordance with the BioBrick assembly standard, which is a molecular cloning method with certain constraints. It requires that certain restriction sites be located upstream and downstream of the plasmid insert, but not anywhere else in the sequence. This enables modular assembly of low-level parts into larger composite parts, and the subsequent assembly of the large parts into even larger constructs without the need for special precautions. The exact strategy including each cloning step and the order in which parts are to be constructed is not shown here. The file contains all of the parts and included hyperlinks to the parts registry. Redundant strategies have been conceived of in order to prevent bottlenecks from arising due to certain parts being faulty. The optimal strategy allows all of the plasmids to be assembled completely by ligation of BioBrick parts. “Emergency” BioBrick part replacement strategies involving PCR have also been developed, and the necessary primers have been designed.

Strains

For all the cloning steps required in this project we will use high copy plasmids in order to make restriction and purification of the plasmids more efficient. The final constructs will be cloned into a low copy plasmid in order to avoid producing too much of the proteins, which could lead to noise related issues and the risk of inclusion body formation.

5. Experimental Design

Once the plasmids have been constructed and transformed into their final host system, the oscillation experiment can be performed. Cells should grow in a container with flowing medium until they reach an adequate cell density, and to then activate the oscillation circuit. Over the course of hours, levels of fluorescent light emission should rise and fall in a synchronized manner.

Fluorescence vs. Visible Light

Detection of the oscillatory behaviour in the previously described designs relies on the excitation of fluorescent proteins and detection their emissions. Replacing the GFP gene with a gene for Luciferase would allow visible-spectrum light to be emitted via a biochemical reaction if the appropriate substrate were added to the medium. Though they fulfil essentially the same function, which one is more suitable depends on the detection devices available and their compatibility with the platform on which the bacteria are grown. However, having visible light detection is a prerequisite for the implementation our advanced design.

Platform

The original Danino & Hasty design is believed to work in part due to the fact that the AiiA gene is longer than LuxI, and therefore the LuxI protein will begin producing the quorum sensing molecule AHL before AiiA is fully expressed. However, once AiiA is present it can degrade AHL faster than it is produced. Achieving oscillatory behaviour via this mechanism does not allow the system many degrees of freedom, and the kinetics involved, both in terms of gene expression and enzyme activity, are crucial. A self-contained system should not have to rely on external manipulation to produce oscillating behaviour. One aspect that can be controlled without compromising the integrity of the system is the rate at which AHL accumulates in the extracellular medium, and by extension, in all of the cells. This control can be provided by growing the cells in container in which they are physically constrained to a small space while a growth medium can flow over them and wash away AHL so that it cannot permanently accumulate, as well as waste and excess cells. It should also allow cell density to reach a stable steady state. The container should also be transparent to allow detection of the reporter molecules.

"

"