Team:Calgary/Project/ProjectPseudomonas

From 2011.igem.org

Rpgguardian (Talk | contribs) |

Rpgguardian (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

<h2>What Are We Looking For?</h2> | <h2>What Are We Looking For?</h2> | ||

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_Looking.png|thumb|400px|right|<b>Figure 1 | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_Looking.png|thumb|400px|right|<b>Figure 1</b> The model naphthenic acid Cyclohexanepentanoic acid and the potential targets which our team was looking for in our screen for a NA responsive element. Our biotinylation/immunoprecipitation technique can be optimized for searching for any of these four response elements. The techniques described further in this document focus on transcription factor and degradation enzyme based optimization.]]<html> |

<p>Due to the complexity of biological systems, our team focused our efforts on identifying a system for identification of proteins or complexes which bind DNA. Transcription factors, which bind to specific elements of a gene known as the promoter, have been well characterized in other metabolic systems to respond to metabolites in the cell and change the level of transcription of particular metabolic response genes. A common example of one of these systems is the lac operon which has been harnessed as a selection system already in the registry. Identifying a system such as this for naphthenic acids, if one exists, would allow for a specific response to be generated to many different kinds of naphthenic acids. Our hypothesis requires that the organisms we use respond specifically to naphthenic acids and result in specific upregulation of metabolic genes with little background effect in the cell. Additionally, numerous protein elements have been shown to bind and modify DNA resulting in downstream changes to protein expression. Examples of thsi are histone modifying enzymes in Eukaryotes which have opened up a new realm of researcher known as epigenetics. These systems can be complicated and often do not directly recognize metabolic chemical compounds. Furthermore, it is possible that naphthenic acids may even interact with specific RNA responsive elements known as riboswitchs which may be involved in the modification of protein expression. While the identification of any of these systems were of specific interest to us to identify a detection system for naphthenic acids, we wanted our approach to be broad enough to idenitfy any components interacting with naphthenic acids.</p> | <p>Due to the complexity of biological systems, our team focused our efforts on identifying a system for identification of proteins or complexes which bind DNA. Transcription factors, which bind to specific elements of a gene known as the promoter, have been well characterized in other metabolic systems to respond to metabolites in the cell and change the level of transcription of particular metabolic response genes. A common example of one of these systems is the lac operon which has been harnessed as a selection system already in the registry. Identifying a system such as this for naphthenic acids, if one exists, would allow for a specific response to be generated to many different kinds of naphthenic acids. Our hypothesis requires that the organisms we use respond specifically to naphthenic acids and result in specific upregulation of metabolic genes with little background effect in the cell. Additionally, numerous protein elements have been shown to bind and modify DNA resulting in downstream changes to protein expression. Examples of thsi are histone modifying enzymes in Eukaryotes which have opened up a new realm of researcher known as epigenetics. These systems can be complicated and often do not directly recognize metabolic chemical compounds. Furthermore, it is possible that naphthenic acids may even interact with specific RNA responsive elements known as riboswitchs which may be involved in the modification of protein expression. While the identification of any of these systems were of specific interest to us to identify a detection system for naphthenic acids, we wanted our approach to be broad enough to idenitfy any components interacting with naphthenic acids.</p> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

<p>Due to the diversity and ambiguity of microbial species in the tailings ponds, we chose to focus our efforts for our promoter search on two species of <i>Pseudomonas</i> and a species of microalgae <i>Dunaliella tertiolecta</i> (<b>please see our chassis section for more information on these species</b>). All of these organisms have been shown to degrade naphthenic acids, however little work has been done in characterizing the degradation pathways of both species.</p> | <p>Due to the diversity and ambiguity of microbial species in the tailings ponds, we chose to focus our efforts for our promoter search on two species of <i>Pseudomonas</i> and a species of microalgae <i>Dunaliella tertiolecta</i> (<b>please see our chassis section for more information on these species</b>). All of these organisms have been shown to degrade naphthenic acids, however little work has been done in characterizing the degradation pathways of both species.</p> | ||

| - | < | + | <h2>Method Design</h2> |

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_IP.png|thumb|400px|right|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_IP.png|thumb|400px|right|<b>Figure 2</b> A typical immunoprecipitation (IP) performed using an antibody raised against a particular protein target. The antibody is incubated with a cell lysate containing purified protein. The antibody will bind to its specific antigen and the solution may be incubated with beads that are capable of binding the antibodies. The beads, coupled to the antibody and protein target can then be isolated from the mixture through the use of a magnet (if the beads are magnetic) or through centrifugation. The protein can be denatured off of the beads and analyzed using mass spectrometry to identify their sequence.]]<html> |

<p>As we plan to screen both bacterial and microalgae species, it was vital that our screening technique be robust and efficient in a variety of cellular systems. It was also important that it selectively targeted protein elements which were specific for naphthenic acids and did not result in unwanted background. A common technique used in similar application including protein biochemistry is immunoprecipitation (IP) for the identification of protein interactors against a particular bait protein. An antibody is incubated with the lysate of the organism of interest. The target of this antibody and its interacting proteins can be isolated using beads that bind to a conserved region opposite the antigen binding domain. Isolation of the target protein along with its interactors allows for their identification through mass spectrometry (MS), a routinely used technique to identify proteins. This technique has been well established and is used routinely in a variety of applications.</p> | <p>As we plan to screen both bacterial and microalgae species, it was vital that our screening technique be robust and efficient in a variety of cellular systems. It was also important that it selectively targeted protein elements which were specific for naphthenic acids and did not result in unwanted background. A common technique used in similar application including protein biochemistry is immunoprecipitation (IP) for the identification of protein interactors against a particular bait protein. An antibody is incubated with the lysate of the organism of interest. The target of this antibody and its interacting proteins can be isolated using beads that bind to a conserved region opposite the antigen binding domain. Isolation of the target protein along with its interactors allows for their identification through mass spectrometry (MS), a routinely used technique to identify proteins. This technique has been well established and is used routinely in a variety of applications.</p> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

<p>In a similar manner we designed a protocol to use naphthenic acids in an immunoprecipitation. This however, required that we develop a system to conjugate our naphthenic acids to a bead platform similar to the commercially available antibodies used in traditional IP. To accomplish this, we attempted to react the conserved carboxylic acid of the naphthenic acid cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA) (<b>see Naphthenic Acid section</b>) with a commercially available biotin-amine derivative. By reacting these compounds in the presence of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) the carboxylic acid and primary amine can produce an amide linkage under low pH conditions. Biotinylation is commonly performed with DNA and protein side chains using commercial kits designed for these applications. However, the biotinylation of small molecules is rare and techniques involving hydrophobic compounds such as CHPA are not found in the literature. This required that we generate a novel protocol for biotinylating CHPA along with other naphthenic acid compounds.</p> | <p>In a similar manner we designed a protocol to use naphthenic acids in an immunoprecipitation. This however, required that we develop a system to conjugate our naphthenic acids to a bead platform similar to the commercially available antibodies used in traditional IP. To accomplish this, we attempted to react the conserved carboxylic acid of the naphthenic acid cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA) (<b>see Naphthenic Acid section</b>) with a commercially available biotin-amine derivative. By reacting these compounds in the presence of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) the carboxylic acid and primary amine can produce an amide linkage under low pH conditions. Biotinylation is commonly performed with DNA and protein side chains using commercial kits designed for these applications. However, the biotinylation of small molecules is rare and techniques involving hydrophobic compounds such as CHPA are not found in the literature. This required that we generate a novel protocol for biotinylating CHPA along with other naphthenic acid compounds.</p> | ||

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_Compounds.png|thumb|400px|left|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_Compounds.png|thumb|400px|left|<b>Figure 3</b> Chemical structure of Cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA), Biotin-Amine, and the final product with an amide bonding formed between the carboxylic acid of CHPA and the primary amine group of the Biotin linker.]]<html> |

<p>Once our naphthenic acid has become biotinylated, the biotin group will strongly interact with a protein known as streptavidin. The biotin/streptavidin interaction is one of the strongest characterized interactions discovered (Kd=1- to the -15M) and is commonly linked to magnetic beads allowing for our biotinylated naphthenic acid to be used in similar protocols as in immunoprecipitation. In theory, proteins which interact with the cyclic ring structure of cyclohexane pentnaoic acid can be isolated using our biotinylated CHPA/strepatividin beads platform and identified. Finally mass spectrometry can be used to determine the identity of these regulatory elements. Figure overall process compared to antibody IP.</p> | <p>Once our naphthenic acid has become biotinylated, the biotin group will strongly interact with a protein known as streptavidin. The biotin/streptavidin interaction is one of the strongest characterized interactions discovered (Kd=1- to the -15M) and is commonly linked to magnetic beads allowing for our biotinylated naphthenic acid to be used in similar protocols as in immunoprecipitation. In theory, proteins which interact with the cyclic ring structure of cyclohexane pentnaoic acid can be isolated using our biotinylated CHPA/strepatividin beads platform and identified. Finally mass spectrometry can be used to determine the identity of these regulatory elements. Figure overall process compared to antibody IP.</p> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | < | + | <h2>Biotinylation</h2> |

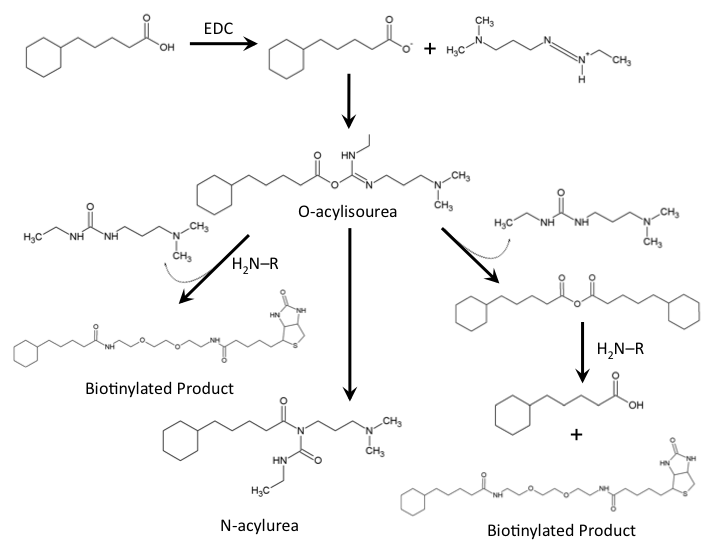

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_ReactionMech.png|thumb|625px|left|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_ReactionMech.png|thumb|625px|left|<b>Figure 4</b> Chemical mechanism for the formation of a amide bond between cylohexanepentanoic acid and a commercially available biotin-amine compound.]]<html> |

<p>The biotinylation of molecules containing carboylic acid groups follows a well characterized reaction mechanism. In the context of our biotinylation reagents (CHPA and Biotin-PEG-amine) the reaction mechanism can be seen in Figure – reaction mechanism. The cyclohexanepentanoic acid will react with the carbodiimide (EDC) to produce an O-acylisourea intermediate activating the carboxylic acid making it an excellent leaving group. This requires a low pH environment to deprotonate the carboxylic acid. From this intermediate the desired product can be produced via direct attack of the negatively charged carboxylic acid with the amine group of our biotinylated compound producing a urea based compound as a by-product. Further reaction of the O-acylisourea intermediate with cyclohexanepentanoic acid may result in an acid anhydride which further reacts to produce the biotinylated compound of interest. The main byproduct of the reaction involves the rearrangement of the O-acylisourea to a stable N-acylurea. Common solutions to reduce the reaction towards this product involves the use of low-dielectric constant solvents such as dichloromethane. Due to the hydrophobic nature of cyclohexanepentanoic acid, aqueous low pH solutions will cause precidpitation of this reaction substrate, therefore, the use of other solvents such as dimethylsulfoxide need to be used. The final reaction solution used in all biotinylation experiments used 9% DCM/ 18% ddH2O / 73% DMSO. Typical reactions run overnight at room temperature. (Please see our protocols page for more information on the biotinylation experiment).</p> | <p>The biotinylation of molecules containing carboylic acid groups follows a well characterized reaction mechanism. In the context of our biotinylation reagents (CHPA and Biotin-PEG-amine) the reaction mechanism can be seen in Figure – reaction mechanism. The cyclohexanepentanoic acid will react with the carbodiimide (EDC) to produce an O-acylisourea intermediate activating the carboxylic acid making it an excellent leaving group. This requires a low pH environment to deprotonate the carboxylic acid. From this intermediate the desired product can be produced via direct attack of the negatively charged carboxylic acid with the amine group of our biotinylated compound producing a urea based compound as a by-product. Further reaction of the O-acylisourea intermediate with cyclohexanepentanoic acid may result in an acid anhydride which further reacts to produce the biotinylated compound of interest. The main byproduct of the reaction involves the rearrangement of the O-acylisourea to a stable N-acylurea. Common solutions to reduce the reaction towards this product involves the use of low-dielectric constant solvents such as dichloromethane. Due to the hydrophobic nature of cyclohexanepentanoic acid, aqueous low pH solutions will cause precidpitation of this reaction substrate, therefore, the use of other solvents such as dimethylsulfoxide need to be used. The final reaction solution used in all biotinylation experiments used 9% DCM/ 18% ddH2O / 73% DMSO. Typical reactions run overnight at room temperature. (Please see our protocols page for more information on the biotinylation experiment).</p> | ||

| - | < | + | <h2>Biotinylation Confirmation</h2> |

<p>In order to confirm the biotinylation reaction was occurring, reverse phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was used. A C18 analytical column from dionex was used on a Dionex <b>Find out lisas stuff</b>, using a protocol adapted from a Dionex provided complex naphthenic acid solutiosn protocol (please see our protocols section for more information).</p> | <p>In order to confirm the biotinylation reaction was occurring, reverse phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was used. A C18 analytical column from dionex was used on a Dionex <b>Find out lisas stuff</b>, using a protocol adapted from a Dionex provided complex naphthenic acid solutiosn protocol (please see our protocols section for more information).</p> | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

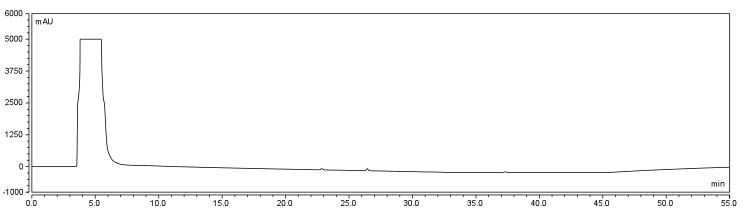

<p>To establish a set of control conditions for this data analysis, DMSO and DCM were individually injected onto the column and a read out at 210 nm on a UV/VIS spectrophotometer over a 60 min.</p> | <p>To establish a set of control conditions for this data analysis, DMSO and DCM were individually injected onto the column and a read out at 210 nm on a UV/VIS spectrophotometer over a 60 min.</p> | ||

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSO_Blank.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSO_Blank.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 5.a</b> Blank run of 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) injected onto a C18 column.]]<html> |

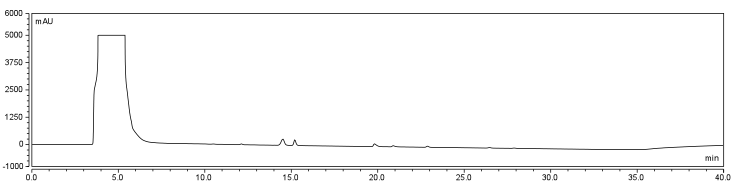

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DCM_Blank.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DCM_Blank.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 5.b</b> Blank run of 100% dichloromethane (DCM) injected onto a C18 column.]]<html> |

<p>Due to the large peak produced by both of these solvents, it was thought that identification of potential aqueous solutions which elute between 3-7 min. of the program may be masked by the large peak produced during elution of DMSO or DCM. Therefore to examine the peaks for the reactants of the solution (biotin, and EDAC) were examined in water solutions. CHPA was diluted in 80% DMSO. Biotin, EDAC, and CHPA were loaded onto the column at 25 uL of 100 mM, 500 mM, and 2mg/mL stock solutions</p> | <p>Due to the large peak produced by both of these solvents, it was thought that identification of potential aqueous solutions which elute between 3-7 min. of the program may be masked by the large peak produced during elution of DMSO or DCM. Therefore to examine the peaks for the reactants of the solution (biotin, and EDAC) were examined in water solutions. CHPA was diluted in 80% DMSO. Biotin, EDAC, and CHPA were loaded onto the column at 25 uL of 100 mM, 500 mM, and 2mg/mL stock solutions</p> | ||

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_Biotin.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_Biotin.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 6.a</b> Biotin control sample injected onto the column. The biotin peak has a retention time between 3-7 min. Therefore when ran with DMSO, the biotin peak will be masked.]]<html> |

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_EDAC.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_EDAC.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 6.b</b> EDAC catalyst sample injected onto the column. Due to the large amount of EDAC loaded onto the column, the peak is above the absorbance limit of the detector. Like the biotin peak, EDAC has a retention time similar to that of DMSO making it impossible to see when running the reaction solution onto the HPLC column.]]<html> |

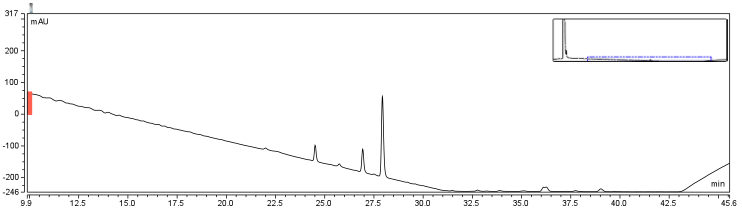

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_CHPA.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_CHPA.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 6.c</b> Control run of cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA) injected onto the column. This produced a specific peak with a retention time of 28 min. Other peaks found in the run correspond to non-specific peaks observed in the DMSO control sample as seen in Figure 1.a.]]<html> |

<p>Due to the retention time of biotin and EDAC being within the rentention time of DMSO, there presence was difficult to detect during the biotinylation reaction. A reaction was set up in 80% DMSO/ 20% ddH2O to test the efficiency of reaction. A control and reaction was set up as written in the protocols section of the wiki, and incubated O/N at room temperature.</p> | <p>Due to the retention time of biotin and EDAC being within the rentention time of DMSO, there presence was difficult to detect during the biotinylation reaction. A reaction was set up in 80% DMSO/ 20% ddH2O to test the efficiency of reaction. A control and reaction was set up as written in the protocols section of the wiki, and incubated O/N at room temperature.</p> | ||

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSOCtrlRxn.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSOCtrlRxn.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 7.a</b> Control of Biotinylation Reaction. Biotin was injected into the column in a solution of 80% DMSO/20% Water. The HPLC graph has been zoomed into the corresponding region identifying the change in peaks between the control and reaction solutions.]]<html> |

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSORxn.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSORxn.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 7.b</b> Reaction solution containing CHPA, Biotin, and EDAC incubated at room temperature for 24 hours. Reaction solution was injected onto a C18 column.]]<html> |

| - | <p>Four peaks were observed in the reaction dataset which was not observed in the control with retention times of 15 min. 19 min. 20 min. and | + | <p>Four peaks were observed in the reaction dataset which was not observed in the control with retention times of 15 min. 19 min. 20 min. and 28 min. The 28 min. peak was found to correspond to the CHPA control. Therefore the remaining three unique peaks were determined to show that the reaction was progressing. Independent HPLC analysis showed that after 24 hours the reaction had gone to completion and there was no difference in peak sizes observed (data not shown). |

In order to further optimize this reaction, the reaction was repeated with and without the use of 9% DCM, in the same conditions as before.</p> | In order to further optimize this reaction, the reaction was repeated with and without the use of 9% DCM, in the same conditions as before.</p> | ||

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSORxn(2).png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DMSORxn(2).png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 7.a</b> Biotinylation reaction in 80% DMSO/20% Water. Samples were incubated at room temperature overnight and injected onto a C18 column using regular protocol.]]<html> |

| - | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DCMRxn.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure | + | </html>[[Image:UofC2011_DCMRxn.png|thumb|625px|center|<b>Figure 7.b</b> Biotinylation reaction in DCM/DMSO/Water. Samples were incubated at room temperature overnight and injected onto a C18 column using regular protocol.]]<html> |

<p>Comparison of the two datasets shows an increase in the three reaction peaks with relatively no change in the CHPA peak, suggesting that dichloromethane’s low dielectric constant increases the relative rate of reaction. Finally, to confirm the identity of our biotinylated product, peak fractions were collected for a potential biotin peak (~9 min.), the peak at 19 min. and the second peak at 20 min. The expected masses of biotin control and the expected products are as follows: | <p>Comparison of the two datasets shows an increase in the three reaction peaks with relatively no change in the CHPA peak, suggesting that dichloromethane’s low dielectric constant increases the relative rate of reaction. Finally, to confirm the identity of our biotinylated product, peak fractions were collected for a potential biotin peak (~9 min.), the peak at 19 min. and the second peak at 20 min. The expected masses of biotin control and the expected products are as follows: | ||

Revision as of 02:02, 28 September 2011

Building a Naphthenic Acid Biosensor

Our team set out to identify a novel responsive element capable of detecting and quantifying naphthenic acids in solution. While numerous studies have begun to identify species of bacteria which can survive and/or degrade NA’s, the pathways of degradation have not yet been characterized. Therefore this goal required our team to design and implement novel methods to isolate the cellular systems of tailing ponds biological organisms which detect and potentially degrade naphthenic acids. We developed a naphthenic acid biotinylation/immunoprecipitation technique which allows for identification of novel protein complexes which interact and may potentially detect naphthenic acids. Our team developed an optimized protocol for the biotinylation of cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA), and a protocol for the immunoprecipitation of Pseudomonas lysates using commercially available streptavidin magnetic beads.

In addition, our team developed an in silico approach to isolating proteins which may be involved in degrading naphthenic acids using two specific species of Pseudomonas previously reported to degrade NA's in co-culture. Through use of various bioinformatic databases, a list of potential naphthenic acid degrading proteins were identified. Of these, a set were tested using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to identify an increase in expression when incubated with naphthenic acids. A novel Enoyl-Coa-hydratase was identified to increase expression when exposed to naphthenic acid, suggesting it may be a responsive element to naphthenic acids.

Click here for more information about our Bioinformatic searchers

Promoter Fishing: Designing A Novel Biotinylation-Immunprecipitation System For Isolation of Naphthenic Acid Interactors

What Are We Looking For?

Due to the complexity of biological systems, our team focused our efforts on identifying a system for identification of proteins or complexes which bind DNA. Transcription factors, which bind to specific elements of a gene known as the promoter, have been well characterized in other metabolic systems to respond to metabolites in the cell and change the level of transcription of particular metabolic response genes. A common example of one of these systems is the lac operon which has been harnessed as a selection system already in the registry. Identifying a system such as this for naphthenic acids, if one exists, would allow for a specific response to be generated to many different kinds of naphthenic acids. Our hypothesis requires that the organisms we use respond specifically to naphthenic acids and result in specific upregulation of metabolic genes with little background effect in the cell. Additionally, numerous protein elements have been shown to bind and modify DNA resulting in downstream changes to protein expression. Examples of thsi are histone modifying enzymes in Eukaryotes which have opened up a new realm of researcher known as epigenetics. These systems can be complicated and often do not directly recognize metabolic chemical compounds. Furthermore, it is possible that naphthenic acids may even interact with specific RNA responsive elements known as riboswitchs which may be involved in the modification of protein expression. While the identification of any of these systems were of specific interest to us to identify a detection system for naphthenic acids, we wanted our approach to be broad enough to idenitfy any components interacting with naphthenic acids.

Napthenic Acid Degrading Organisms To Be Used

Due to the diversity and ambiguity of microbial species in the tailings ponds, we chose to focus our efforts for our promoter search on two species of Pseudomonas and a species of microalgae Dunaliella tertiolecta (please see our chassis section for more information on these species). All of these organisms have been shown to degrade naphthenic acids, however little work has been done in characterizing the degradation pathways of both species.

Method Design

As we plan to screen both bacterial and microalgae species, it was vital that our screening technique be robust and efficient in a variety of cellular systems. It was also important that it selectively targeted protein elements which were specific for naphthenic acids and did not result in unwanted background. A common technique used in similar application including protein biochemistry is immunoprecipitation (IP) for the identification of protein interactors against a particular bait protein. An antibody is incubated with the lysate of the organism of interest. The target of this antibody and its interacting proteins can be isolated using beads that bind to a conserved region opposite the antigen binding domain. Isolation of the target protein along with its interactors allows for their identification through mass spectrometry (MS), a routinely used technique to identify proteins. This technique has been well established and is used routinely in a variety of applications.

In a similar manner we designed a protocol to use naphthenic acids in an immunoprecipitation. This however, required that we develop a system to conjugate our naphthenic acids to a bead platform similar to the commercially available antibodies used in traditional IP. To accomplish this, we attempted to react the conserved carboxylic acid of the naphthenic acid cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA) (see Naphthenic Acid section) with a commercially available biotin-amine derivative. By reacting these compounds in the presence of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) the carboxylic acid and primary amine can produce an amide linkage under low pH conditions. Biotinylation is commonly performed with DNA and protein side chains using commercial kits designed for these applications. However, the biotinylation of small molecules is rare and techniques involving hydrophobic compounds such as CHPA are not found in the literature. This required that we generate a novel protocol for biotinylating CHPA along with other naphthenic acid compounds.

Once our naphthenic acid has become biotinylated, the biotin group will strongly interact with a protein known as streptavidin. The biotin/streptavidin interaction is one of the strongest characterized interactions discovered (Kd=1- to the -15M) and is commonly linked to magnetic beads allowing for our biotinylated naphthenic acid to be used in similar protocols as in immunoprecipitation. In theory, proteins which interact with the cyclic ring structure of cyclohexane pentnaoic acid can be isolated using our biotinylated CHPA/strepatividin beads platform and identified. Finally mass spectrometry can be used to determine the identity of these regulatory elements. Figure overall process compared to antibody IP.

Biotinylation

The biotinylation of molecules containing carboylic acid groups follows a well characterized reaction mechanism. In the context of our biotinylation reagents (CHPA and Biotin-PEG-amine) the reaction mechanism can be seen in Figure – reaction mechanism. The cyclohexanepentanoic acid will react with the carbodiimide (EDC) to produce an O-acylisourea intermediate activating the carboxylic acid making it an excellent leaving group. This requires a low pH environment to deprotonate the carboxylic acid. From this intermediate the desired product can be produced via direct attack of the negatively charged carboxylic acid with the amine group of our biotinylated compound producing a urea based compound as a by-product. Further reaction of the O-acylisourea intermediate with cyclohexanepentanoic acid may result in an acid anhydride which further reacts to produce the biotinylated compound of interest. The main byproduct of the reaction involves the rearrangement of the O-acylisourea to a stable N-acylurea. Common solutions to reduce the reaction towards this product involves the use of low-dielectric constant solvents such as dichloromethane. Due to the hydrophobic nature of cyclohexanepentanoic acid, aqueous low pH solutions will cause precidpitation of this reaction substrate, therefore, the use of other solvents such as dimethylsulfoxide need to be used. The final reaction solution used in all biotinylation experiments used 9% DCM/ 18% ddH2O / 73% DMSO. Typical reactions run overnight at room temperature. (Please see our protocols page for more information on the biotinylation experiment).

Biotinylation Confirmation

In order to confirm the biotinylation reaction was occurring, reverse phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was used. A C18 analytical column from dionex was used on a Dionex Find out lisas stuff, using a protocol adapted from a Dionex provided complex naphthenic acid solutiosn protocol (please see our protocols section for more information).

The HPLC conditions used for the analysis was as follows. A 60 min. program was designed with a mobile phase of 40% Acetonitrile / 60% 0.1% TFA Water with a gradient from 3-28 min. changing to 85% Acetonitrile/15% 0.1% TFA holding until 40 min. The final 20 min. of the program ramped back to original gradient to clean the column. A 25 μL sample loop was used and the injection was loaded onto the column at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min at a temperature of 30 To establish a set of control conditions for this data analysis, DMSO and DCM were individually injected onto the column and a read out at 210 nm on a UV/VIS spectrophotometer over a 60 min. Due to the large peak produced by both of these solvents, it was thought that identification of potential aqueous solutions which elute between 3-7 min. of the program may be masked by the large peak produced during elution of DMSO or DCM. Therefore to examine the peaks for the reactants of the solution (biotin, and EDAC) were examined in water solutions. CHPA was diluted in 80% DMSO. Biotin, EDAC, and CHPA were loaded onto the column at 25 uL of 100 mM, 500 mM, and 2mg/mL stock solutions Due to the retention time of biotin and EDAC being within the rentention time of DMSO, there presence was difficult to detect during the biotinylation reaction. A reaction was set up in 80% DMSO/ 20% ddH2O to test the efficiency of reaction. A control and reaction was set up as written in the protocols section of the wiki, and incubated O/N at room temperature. Four peaks were observed in the reaction dataset which was not observed in the control with retention times of 15 min. 19 min. 20 min. and 28 min. The 28 min. peak was found to correspond to the CHPA control. Therefore the remaining three unique peaks were determined to show that the reaction was progressing. Independent HPLC analysis showed that after 24 hours the reaction had gone to completion and there was no difference in peak sizes observed (data not shown).

In order to further optimize this reaction, the reaction was repeated with and without the use of 9% DCM, in the same conditions as before. Comparison of the two datasets shows an increase in the three reaction peaks with relatively no change in the CHPA peak, suggesting that dichloromethane’s low dielectric constant increases the relative rate of reaction. Finally, to confirm the identity of our biotinylated product, peak fractions were collected for a potential biotin peak (~9 min.), the peak at 19 min. and the second peak at 20 min. The expected masses of biotin control and the expected products are as follows:

Samples were collected from the HPLC in 30 sec. fractions of 0.3mL and dried down in a vacufuge at 45C. Samples were submitted to the University of Calgary Department of Chemistry MS Facility for electrospray analysis.

Figure MS results (3 graphs)

MS analysis identified the control Biotin at the correct size as determined by the literature. The peak at 19 min. corresponds to the size of Biotin-CHPA plus a sodium ion (22.99 Da) which is found in high quanitites in the methanol used in electrospray which may be responsible for the higher peak size identified. Finally, the peak at 20 min. corresponded to the N-acylurea, the by-product of the reaction. This was an interesting result as it suggests that the DCM provided in the solution (as shown in Figure reaction DMSO, reaction DCM) did not decrease the relative amount of byproduct to biotinylated-CHPA, but the overall use of biotin in the solution, perhaps through increasing the degree of intermediate formation during the first steps of the reaction.

From the electrospray data, the peak at a retention time of 19 min. was determined to be the biotinylated product.

Immunoprecipitation and Future Directions

With the success of our biotinylation reaction, our team attempted to select for our biotinylated compound by directly incubating the biotin reaction solution with streptavidin coated magnetic beads. After reacting a biotinylation solution with 50 ug of streptavidin coated beads at 4C for 2 hours, it was identified through HPLC analysis that there was no binding of the biotin-CHPA product to the streptavidin (data not shown) likely due to the high concentration of DMSO and DCM in the solution. In order to produce a more favorable solution for this binding to occur, the reaction solution was diluted from 200 uL to a volume of 2 mL using 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 and again the beads were allowed to incubate. Once again no binding was observed when both solutions were ran using HPLC analysis. Figure streptavidin binding

No observed difference in peak height could be identified for the 19 min. peak suggesting that the biotin was not binding to the streptavidin beads. Furthermore, performing an IP using beads incubated with this reaction solution did not result in any specific bands (data not shown). This was likely due to the precipitation of the CHPA when the Tris pH 7.5 solution was added to the reaction mix. In order to successfully bind the biotinylated product to the beads, it may be required to increase the pH of the solution to 8-8.5 to ensure the CHPA will remain in solution. Unfortunately due to time constraints the University of Calgary team has not had sufficient time to complete these experiments.

In the future we hope to continue optimizing the streptavidin bead/biotinylation binding in order to perform the IP based experiments explained earlier in this document. By modifying the pH of the solution, or by attempting to slowly titrate in our reaction solution into an aqueous bead solution, our dilemma will hopefully be solved.

Conclusions

A novel system for biotinylating cyclohexanepentanoic acid as well as other model naphthenic acids has been identified and confirmed using HPLC and MS analysis. While further optmization of the protocols is required before performing IP based experiments, this technique has provided the first steps towards a novel system to detect and isolate proteins involved in the naphthenic acid detection pathways of Pseudomonas and microalgae.

"

"